Abundance Should Not Erase the Traditional Republican

Reaganism still has something to teach us

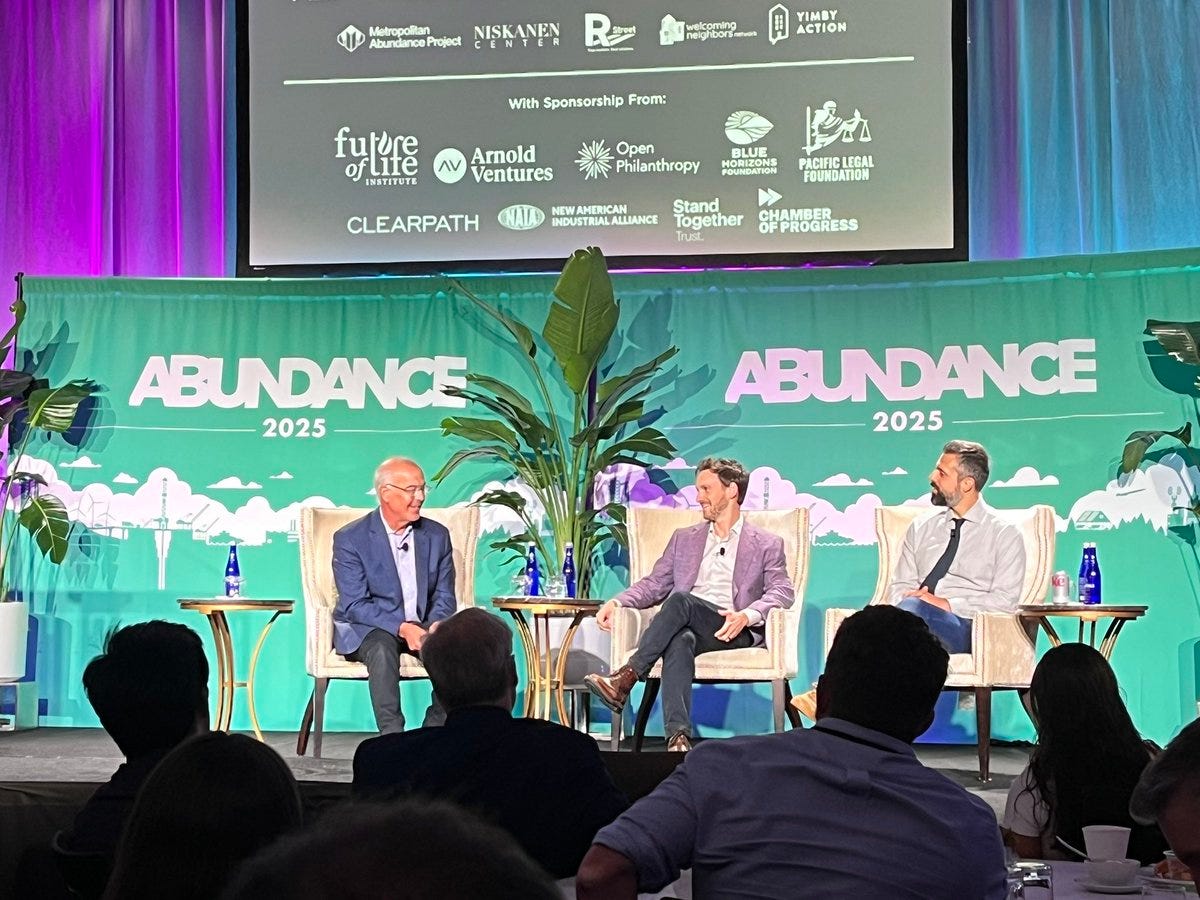

Last Thursday and Friday, I was at the Salamander Hotel for the Abundant DC conference. I had never been to a left-wing political conference before, and was interested not only in the exploration of the ideas, but also the coalitions that were taking shape, how I would be received by others, and the general atmosphere.

The first thing I noticed was the bipartisan nature of the guest list. The first panel included three members of Congress, two Democrats (Ritchie Torres, Josh Harder) and a Republican (Celeste Malloy). A man sat next to me at the event, and he turned out to be the mayor of Chattanooga. Utah governor Spencer Cox (R) was there. Among intellectuals, the headliners were Thompson, Yglesias, and Klein, yet there was also Reihan Salam, among others, on behalf of conservatism, and even former Trump administration officials or MAGA-adjacent figures like Oren Cass and Dean Ball, though Cass took an adversarial role in his discussion with Yglesias (more on that soon).

Abundance is usually framed as an intra-coalitional fight under the Democratic umbrella. But it clearly seeks to be something much larger. Truly victorious movements do not become identified with one side of the political aisle. Mothers Against Drunk Driving spearheaded a social movement that made operating a vehicle while intoxicated into a serious crime everywhere while stigmatizing the practice. Deregulation in the late 1970s and 1980s spanned both the Carter and Reagan administrations. Part of the reason the Epstein hysteria is so out of control is that the entire political spectrum is into panics over pedophilia and human trafficking.

The diverse political turnout at Abundance indicates that it is winning. By random chance, while there I learned that Oak Lawn, the small town I grew up in outside of Chicago, was about to eliminate parking requirements. I was surprised, as this was one of the least sophisticated places one could imagine, full of lower class immigrants and white ethnics. Yet the message of abundance had reached one member of the village board and nobody was bothering to resist.

Abundance has been so successful that people are now talking about subtypes of abundance that span the political spectrum. During the conference, I read Steven Teles’ recent piece on the topic. He breaks abundance down into six categories

Red Abundance: Socialist inclined leftists who want to get things done

Cascadian Abundance: Environmentalists who understand that city living is better for the planet

Liberal Abundance: Derek and Ezra, pretty much

Moderate-Abundance Synthesis: Abundance as a tool of the Democratic Party to make it more electable and responsive to the needs of voters

Abundance Dynamism: Tech-bro futurism

Dark Abundance: Right-wingers, leaning towards the Republican Party and MAGA, worried about bureaucrats and China

I appreciate this schema, but as someone closer to the right end of this spectrum, I found the discussion of the last two incomplete. Teles puts national security concerns at the center of Dark Abundance, with the abundance framework serving as a way to cut through sclerosis and red tape, adopt a geopolitically-focused industrial policy, and meet threats from abroad. This can be seen as a combination of a smarter version of DOGE plus hawkishness on China.

The last two categories do capture distinct tendencies on the right, but I think that there’s another version of right-wing abundance with real world influence that is getting shortchanged. It is somewhat implicit in the last two, but deserving of its own category, and also apparent in the Moderate-Abundance Synthesis (#4):

The politics of MAS are much more explicitly partisan than single-issue. The most distinctive example of MAS at the urban level is GrowSF, which seeks to build political power through a fusion of traditional Abundance priorities like housing and transportation with “moderate” priorities like crime prevention, back-to-basics education and school choice, and a more assertive policy toward the homeless in public spaces. The failures of urban Democrats are becoming harder to deny, but the nationalization of politics means that Republicans can’t take advantage of them. Abundance, state capacity, and moderation provide a genuinely ambitious governing agenda for Democrats in blue places, and a coalition of wealthy donors and moderate voters makes them electorally potent. In the single-party Democratic politics of big cities, MAS has a fairly obvious lane to pitch itself as the alternative to the governance of the party’s left.

There is a symbiosis here between YIMBYism, school choice, and crime prevention. There are many social and economic benefits to living in a large city. People are often prevented from doing so by high housing costs, crime, and bad schools. Some cities, like Milwaukee, Detroit, and Baltimore, have dirt cheap housing, but still nobody wants to move there. In Detroit, the government at one point was having trouble selling abandoned homes for $1. The reasons are obvious enough, with many Midwestern cities having murder rates that rival those of some of the most violent Latin American countries. Moreover, if you’re going to have kids, the public schools that you support with your taxes are practically unusable.

A central lesson of abundance is you want housing to be affordable because supply can rise to meet demand, not because demand has crashed. If city living has benefits in terms of making people more social and productive, then one cannot ignore the fundamental importance of public safety and the schools question.

Teles presents this set of issues as representing the moderate Democrat position, but they have traditionally been Republican priorities. The Trump administration at least talks tough on crime, even if its methods for tackling the issue have yet to show real effect. Across the country, red states have one after another been adopting universal school choice or education savings accounts. And Klein and Thompson discuss how Republican areas of the country have gotten the housing issue correct, which explains why they have been gaining residents at the expense of liberal locales.

Public safety, markets, and individual liberty. This sounds like standard Reaganism! And although at the national level, the MAGA movement has gotten away from the latter two, they remain strong at the state level. Abundance clearly sees this kind of Republican as an ally, as seen in the fact that the keynote discussion on the first night of the conference was an interview with Utah Governor Spencer Cox. See also the speech of Chris Barnard.

Another place Reaganism can potentially contribute is on the issue of entitlements. The US is headed towards a fiscal crisis in the 2030s, as a result of Social Security and Medicare paying out more money than they are taking in. Older people are wealthier than younger Americans, and I don’t know of any value system that implies government should bankrupt future generations by redistributing money from a poorer demographic to a richer one. If you worry about the fertility crisis, then this is another reason that it is a bad idea to take money away from people in the years in which they reproduce just to make them better off when they can’t. I have always thought that if the luminaries of the abundance movement were designing the welfare state from scratch, they would not choose a system like this.

Reagan Abundance, if we want to call it that, may or may not be too concerned with China, and could want a resurgence in family formation and traditional moral values rather than tech futurism. Alternatively, it may remain agnostic or neutral on cultural issues. The point is that it would see economic freedom as both a moral good and the best way to make humanity wealthier. On issues like labor unions and entitlements, it would take the insights of the abundance movement to their logical conclusions, treading where most Democrats dare not go.

Teles’ scheme focuses on the national political discussion, and there it appears that conservatism is a coalition of industrial policy types, China hawks, and tech bro futurists. Beneath the surface, however, the Reagan consensus remains strong. And it has worked! It is a tribute to both these ideas and the integrity of the abundance movement that it acknowledges that Florida and Texas have gotten the most important cost-of-living issue correct, while New York and California haven’t. The fact that Trump’s obnoxious policies on tariffs and immigration haven’t completely sunk the economy yet is due to other aspects of the conservative agenda being correct.

Here, the reader might be asking: Who cares? What does it matter if we have two or three or four versions of conservative abundance in our head? If Red States are getting the same policy results by calling it “conservatism” or even MAGA, then great. The problem is that many of these ideas are on the defensive within conservatism. As Phil Magness points out in an excellent X post, the postliberal wing of the right is ascendant, and it has made hostility to libertarian economics central to its identity. At the same time that liberals are acknowledging that important aspects of Reaganism work, conservatives have begun to decide that it doesn’t because it does not address ethnonationalist concerns. Fair enough, Ronald Reagan was in fact unconcerned with demographic change. Perhaps even more damagingly, the postliberals have invented a new version of economics to reverse engineer the instincts of Trump and the less educated voters he has brought into the Republican tent. Postliberals will brag that Florida is doing better than the West Coast at the same time they say that the Reagan consensus has failed, attributing the differences in affordability to the degree to which states are woke or whatever.

The question for the future is whether the left-wing and often crank economic ideas being embraced by MAGAs and postliberals at a national level will eventually filter down to the states. If left-leaning wonks are the only people appreciating the extent to which conservative ideas have worked, then in the coming years they will have a much more limited influence on the American right. Often, the point of naming a set of ideas is to grant them a certain status, and give people another conceptual option in terms of how they perceive their own relationship to ideas. And at this point, those of us who are abundance-pilled on the right are losing the internal debate within the conservative coalition, even as our ideas are praised from the outside.

Embracing a normie Republican version of abundance can also help conservatism in the areas where it falls short. For example, I’ve mentioned the importance of crime prevention. But although Republican states tend to avoid scenes like the dystopian nightmare of the Tenderloin district of San Francisco, they haven’t done that great of a job keeping their residents safe. Unless you are going to go full Bukele, and our Constitution prevents this, it doesn’t appear that being tougher on crime does all that much.

Conservatism as currently practiced doesn’t have many ideas here, but engagement with more wonky abundance types can provide a way forward. The most promising avenues for fighting crime appear to involve surveillance, in the form of policies like widespread facial recognition and the extensive use of DNA databases. Such methods tend to be opposed by elements on the left that downplay the importance of fighting crime, and while conservatives might object to them less in theory, there seem to be few serious attempts to engage with the academic literature here for the purposes of implementing smarter approaches.

One of the most encouraging aspects of Abundance DC was seeing the bipartisan nature of the coalition that was forming. Yet while this is an ideology that has been winning over elites on both sides of the political spectrum, the national agenda of the right is increasingly driven by rage coming from below, which is being channeled into foolish policy programs by ambitious politicians and aspiring wonks. I’m optimistic that abundance is the near-term future of the Democratic Party. Unless something changes, however, the right will be increasingly embracing discredited ideas despite the legitimate accomplishments it can point to in its recent past.

While I think we need to pay attention to the bad fiscal forecast, your argument about old age entitlements always seems confused to me.

Elderly people have higher wealth on average because most of them have been saving for retirement. They need entitlements on top of that because some of them haven't saved, and (due to short term bias and planning that takes entitlements for granted) almost none of them have saved enough to maintain their standard of living in retirement.

Since old people's labor is not very productive, wealth plus entitlements is their sole source of consumption. So they are mostly in a worse position when it comes to real spending power than younger people.

The word "Abundance" clearly has a technical meaning unfamiliar to me. A link to an explanation would be nice, particularly as, given that it's a repurposed common english word, google is quite likely to offer readers little that is relevant to this meaning.

I am vaguely familiar with a political position that thinks we (world, or nation) have enough that we don't need to have anyone desperately poor, and should support everyone at a basic level, without a giant bureaucracy verifying true need, let alone term limits for welfare recipients. But from context, I don't think this is what Abundant DC wants - from reading your article, it almost seems as if their main goal is to farther increase the concentration of people in cities, particularly the larger ones, basically by making large cities more livable.