Fertility as the Final Boss in Chinese Development, and Richard Hanania Prediction Markets

Predictions, January 2022

In the spring, I explained how I would be holding myself accountable for predictions, as all public intellectuals should. The idea was that I would report how my portfolio was doing on PredictIt. At the time, I wrote

I began betting on politics in fall 2018. Since that time, I’ve invested $15,700. I’ve taken out $10,000, and the current value of my portfolio is now approximately $29,000. This means that I have so far made 2.5x my original investment, which makes me feel pretty good about myself. This underestimates how well I’ve done, as PredictIt takes 10% of your winnings. That’s 10% of each successful bet you’ve made, not 10% of your net profits, making it more impressive. (i.e., imagine you win $100. They then take $10, then if you lose $100, you’re down to -$10 in net profit, and then if you win $100 again, they take another $10, and you’re only up +$80. So you’ve won $100 twice, and lost $100 once, but instead of your total payout being $100 or $90, it’s $80. You need to consistently beat the market just to break even)

PredictIt is a good way to keep track, because you’re either in the black or red.

So what’s happened since then? As mentioned in the quote above, in the spring I had a portfolio worth around $29,000. I’ve withdrawn $4,000 from my account, and the current portfolio value is $27,100. This means that if I’d kept that money in, I would have been at $31,100, meaning I’ve still been beating the market.

My two big electoral predictions – that Biden and Trump would be the nominees in 2024 – are holding steady or looking better. Trump has gone from 26% to 40%, and Biden is still practically unchanged at 38%. It’s not just PredictIt that’s underestimating Biden and Trump, as Election Betting Odds reflects even less faith in them elsewhere. In other words, this isn’t because PredictIt has an $850 limit on contracts. I also thought Cuomo would survive in New York and took a beating on that.

The problem with continuing to rely only on PredictIt for this is that it’s mostly about American politics, while I would like a mechanism to make predictions about other things.

A friend recommended I try Metaculus and keep track there. The problem here is there’s no simple metric that can tell me whether I’m doing well or not, like the black/red distinction on PredictIt. Metaculus gives you a Brier score, and here’s an explainer of what that is.

So if I predict for example that something will happen with 80% probability and it does, then for that prediction I get (0.8 - 1)^2 = 0.04. If it doesn't, then the contribution of that question is (0.8 - 0)^2 = 0.64. In the version of the Brier score from Metaculus I will use, your score is calculated based on your prediction when the market closes, with most markets closing well before they’re decided. The score goes from 0 to 1, with lower obviously better.

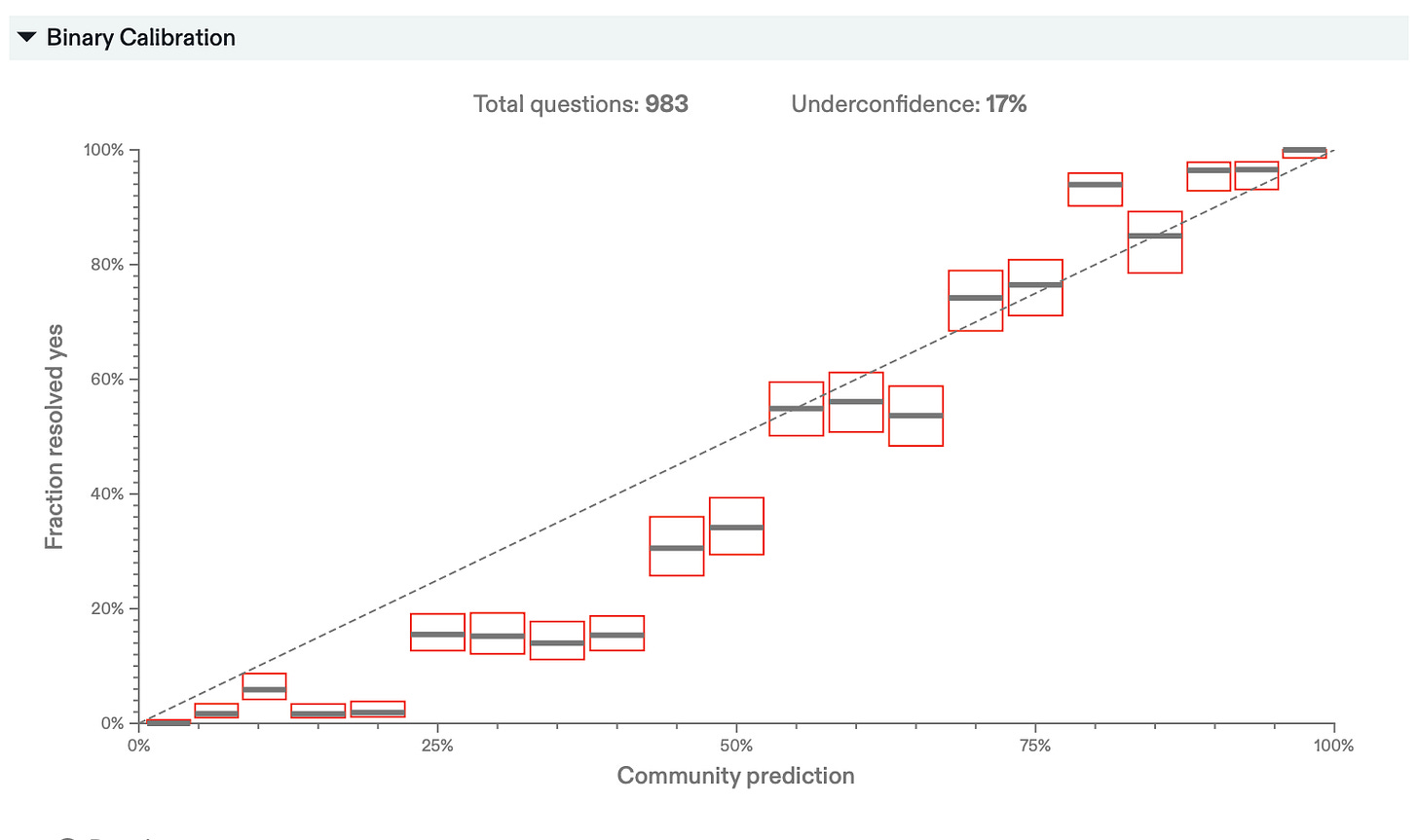

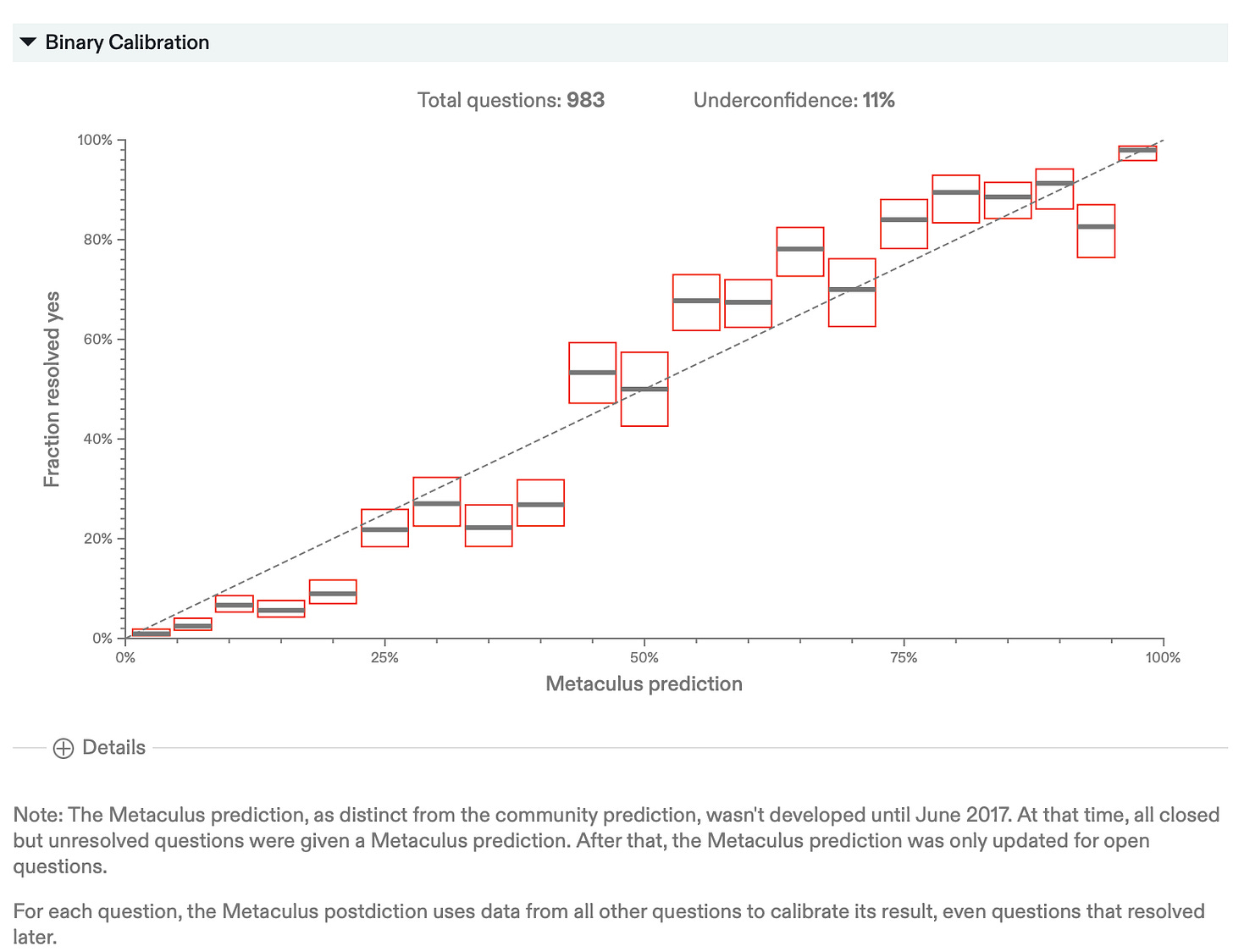

But there’s no clear measure of what a “good” or “bad” score is. Ideally, you want to be able to make a chart that looks like a better calibrated version of the one below, which reflects the predictions of the Metaculus community.

The website seems to overestimate the probability of low probability events, and slightly underestimate the probability of high probability events. In other words, up to this point you could have beaten the crowd on Metaculus by finding things with less than 50% probability and judging them even less likely, and finding things at over 65% probability and giving them slightly higher odds. But overall, the market seems to know what it’s doing when it moves away from long-shot events, and is infinitely superior to punditry, where people just make things up. It would most certainly be much better if it allowed actual money, and the calibration chart looks better when weighted towards the predictions of the most accurate forecasters.

I’m told that when you make enough predictions, you not only get your Brier score, but also your own personal binary calibration chart like the ones above, and eventually I’ll be able to use that to eyeball how I’ve been doing.

So I will keep using PredictIt and reporting how my portfolio is doing, while also working off of Metaculus to test my knowledge about broader geopolitical and other kinds of issues. In the rest of this post, I’ll start with what I think is one of the most important questions facing humanity, move on to other predictions, and then explain what I’m doing on a new website called Manifold Markets.

Chinese Fertility

A week ago I sent out the following tweet.

This inspired a Metaculus question on what Chinese TFR will be in 2031. China has consistently embarrassed western pundits, having become, depending on how you measure, either the largest or second largest economy in the world, without having to undergo political liberalization. Its growth has been on a historically unprecedented scale, based on manufacturing and unusually high levels of technological innovation, while the state has also maintained internal peace and security, whatever we think of its methods for doing so. I’ve written on these themes in a report for Defense Priorities. The American discussion about the rise of China has been a series of copes: the economy is going to collapse, people will demand democracy when they get rich, COVID will end the CCP, America can stop them if we cut off trade and technology transfers, etc.

Recently, I’ve noticed a rise in a new kind of Sino-pessimism that goes along the lines of “sure, our pundits were wrong in the past, but Chairman Xi is stupid and has lost his mind.” Maybe he has, but it’s still too early to say that. Here’s a tweet thread I wrote in response to a Tyler article on the topic.

And, just to demonstrate a common phenomenon, here’s a recent cope from Lyman Stone, who points out China’s GDP per capita is the same as Mexico’s so it’s not really that impressive, without noting that the latter was something like 15 times wealthier in 1980.

But while most China analysis is cope, those who see trouble on the horizon due to low fertility may be on to something. Population size is a fundamental determinant of economic vitality, geopolitical power, and societal health.

And China is getting serious about turning around its fertility problem. What are its prospects for success? The pessimistic case goes like this: practically all countries experience declining fertility as they get wealthier. This is particularly bad in East Asia, where they have the lowest birth rates in recorded history. China had the disastrous one-child policy and artificially depressed its birth rate early, and there’s no reason to think they can turn it around. Removing the one-child policy has not led to any increase in births so far, though it’s early. This is what Anatoly Karlin says, and I usually agree with him on most things.

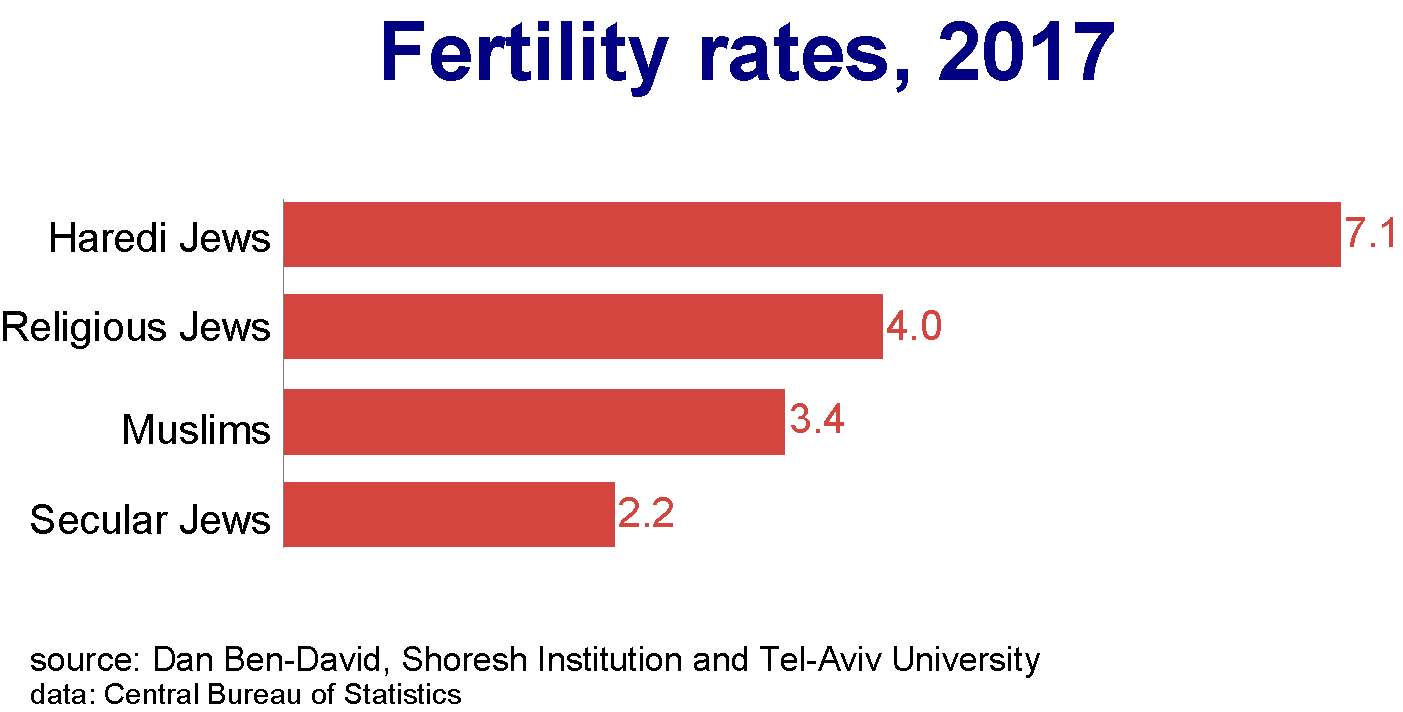

My argument in response has three pieces: 1) fertility is largely a cultural issue, not simply an economic one; 2) the Chinese government is very competent; and 3) it has the tools to fundamentally change the values of society and the willingness to use them. On the first premise, let’s look at fertility rate by religious affiliation in Israel as of 2017.

Basically, people living in the same country can have massively different fertility rates that can’t be explained by economic differences. You’ll never find data like this between social classes, showing that a group with one income has 3-4x the birth rate of those of another income, unless you slice economic bands quite narrowly, and even then it’s usually still the cultural, religious, or ethnic confounders that seem to have the causal effect. Unquestionably, economic development matters too, and there is a trend toward lower fertility as countries get wealthier. But there can be a lot of variation within a country or socioeconomic group, and that must be due to culture.

So we can reject the simple version of economic determinism. This view puts a lot of stock in the fact that other countries have tried to increase their birth rates with little success, and we can reference Lyman Stone here again. Yet I don’t think that what democracies, or even soft authoritarian places like Singapore, have been able to do tells us much about what is possible in China.

To understand why, imagine people are trying different weight loss plans. A tries doing a lot of cardio, B tries weightlifting and C does both. Nobody ever cuts their calories, which is the most important factor in losing weight. Some social scientist comes along, runs the data, and says losing weight is impossible! This would be a pretty bad social scientist.

Fertility research is a lot like that. Broadly speaking, once a country reaches a certain level of development, culture seems to be the most important determinant of fertility, both within and across nations, and few states have shown the willingness and capability to fundamentally shift culture in a pro-natalist direction (Israel and Mongolia seem to be notable exceptions, though no one as far as I can tell knows anything about the latter. My pet theory is that the memory of Genghis makes them feel virile, which I like so much that I don’t think I want to hear any other explanation). Sure, some make halfhearted efforts in that direction; see the “Do it for Denmark” campaign, and South Korea’s creation of a map of fertility by region, which led to a backlash from feminists that caused the government to back down. Yet these are drops in the ocean, and for most governments I’m sure that pro-natalist messaging coming from the state is more than drowned out by feminist and anti-natalist messaging, mostly produced by the education system.

China can simply do away with certain words, phrases, and concepts. It can tell people to believe certain things and not others, and shut down entire industries that get in the way of what the state wants to accomplish. The wars against feminism, effeminate men, excessive studying, and video games can be seen in this context, and we should at least wait some years to see what happens to the fertility rate before listening to western pundits declaring these to be foolish policies. China can also coordinate in a consistent way across various parts of the government, and not be like South Korea, with some officials within the state encouraging higher birth rates and others running something called the “Ministry of Gender Equality and Family”. Not that culture in South Korea depends more on government policy than television dramas and K-pop anyway. By focusing on economics, everyone else is trying cardio, while China is going to cut calories.

This is to a large extent speculation. Do we at least have any precedent of an authoritarian state actually being able to brute force its way to a higher birth rate? I give you communist Romania:

In 1966, Romania’s TFR was 1.9. In 1967, it was 3.67. While it came down almost immediately, Romania still had a higher TFR than its neighbors into the early 1980s, despite starting lower than most of them. I’m not an expert on how this was done, but I understand it was not something anyone should want to emulate. Still, I’m here to make predictions, not pass moral judgments, and we at least have proof of concept that a rapid and substantial rise in fertility is possible with an authoritarian government.

Of course, modern China is not 1960s Romania. It’s less rural, more economically developed, and more connected to global culture, which can be bad for fertility. On the other hand, China has more resources to throw at the problem, modern communications technology that can be put towards propagandizing the state line, and a more competent government, which includes a developed and effective censorship apparatus. Moreover, the measures Beijing has taken to deal with the threats of Hong Kong and Uighur separatism, along with its so-far (maybe not for long) successful Zero Covid policy – again, these are comments on effectiveness, not moral judgments – indicate that the Chinese government is willing not to be restrained by human rights norms when they conflict with state policy. Although I think the tradeoffs no longer make the current policy worth it, I don’t think we’re nearly impressed enough with how China has handled COVID, especially given that they went first and everyone else had at least some warning of what was coming.

How do all these factors balance out? I’m not sure, but I lean on the side of optimism. Smart people disagree, and it will be very interesting to find out who is right.

I hope China does not follow the path of 1960s Romania, but I do hope it can find some path out of the death spiral modern societies find themselves in.

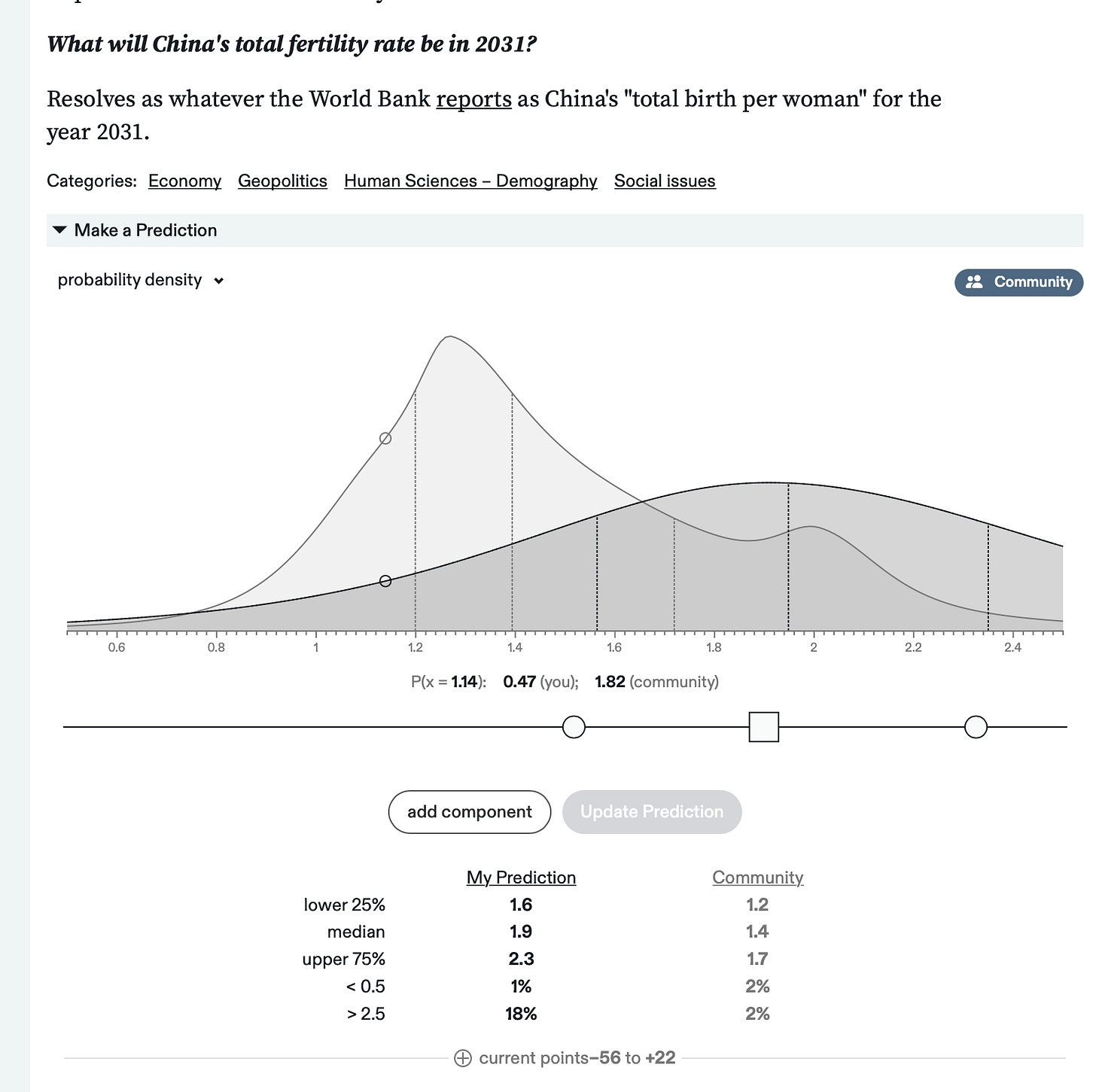

State media reports that Chinese TFR has dropped to 1.3 during COVID-19. My prediction for 2031 is 1.9, with a 50% confidence interval of 1.6 to 2.3. Not many people agree with me, as the Metaculus community has it at 1.4, just barely above the current rate, with a range of 1.2 to 1.7. Because of the importance of this question, and the fact that I disagree so strongly with others, it’s worth highlighting my prediction.

There’s also a question about Hungarian fertility in 2031 (currently around 1.5). I think having a government that cares about the issue and propagandizes on it matters, but I wouldn’t be as optimistic as I am about China. I’m predicting 1.8, which is about similar to what I think China will be in 2031, but with a smaller range. I’m pretty close to the consensus on this one, just slightly more optimistic.

Other Predictions

Here are some other predictions from Metaculus, broken up by American and international. Note that “by/before year X” means by the end of the previous year, so “by 2031” means “by December 31, 2030,” not the end of 2031.

My relative optimism about Republicans winning in 2024 is that I think by becoming so completely a TV watchers party they’ve mastered electoral politics, especially when they’re in opposition and can’t be held responsible for anything. Being able to get away with saying anything because your base doesn’t care about logical consistency or political philosophy is a huge advantage. So is always having a unified message of hatred towards the other side, even when, like in the case of the Afghanistan withdrawal, Biden was just doing what Trump wanted to.

Republicans have been the TV party for decades, but their tendencies have grown more extreme. And in my framework, that’s good for winning elections, even if bad for policy implementation.

The Hanania Prediction Market

A former Google engineer named Austin Chen left a comment on my Reflections on 2021, talking about his new prediction market website, Manifold Markets. He and his co-founders James Grugett and Stephen Grugett just received an ACX grant to work on it.

What’s cool about this site is that it allows anyone to make their own private prediction market and then judge the results. This allows one to draw up subjective questions like “Will there be an elite consensus that the majority of society should return to normal with no Covid precautions by Feb 14th?” It also allows relatively unimportant things that may not matter to a broad audience, like “Will my Sundance trip still happen?”

When you sign up, you get 1,000 Manifold Dollars, which you can’t redeem for cash yet, but which Austin tells me has a “street value” of $10. The site has only been around for about a month, and I’m impressed with how user friendly it is. You don’t actually enter the probabilities of what you think will happen like on Metaculus, you just see where the market is on any particular question and buy “Yes” or “No,” which adjusts the price. You can put money in but you can’t take it out as far as I can tell, though eventually you may be able to. The details are still to be worked out.

Anyway, I decided to draw up a few questions, one China-related to reflect my contrarian Sino-optimism again, and others that are personal. On the China question I started the market at 34%, where I think it should be. For the Hanania-related questions, I’m arbitrarily setting the odds at 50% to begin. I don’t have any specific specialized insider knowledge on any of these, i.e., I have no plans at the moment to go to Washington, D.C., and no op-eds soon to be published in the NYT.

Will Richard Hanania have 50,000 Twitter followers by the end of 2022?

Will Richard Hanania step foot in Washington, D.C. in 2022?

Will Richard Hanania publish at least 70 Substack posts in 2022?

Will Richard Hanania get on Tucker Carlson Tonight at least once in 2022?

If you have any other suggestions, I will be happy to consider them.

Thanks for the shoutout! We've seen a spike in new users coming from your post, and a lot of betting activity on your markets (for the audience: you can find them grouped together at https://manifold.markets/RichardHanania).

The section on prediction calibration is a great explainer of some issues around evaluating how well a predictor did. In markets, you can output a return on investment, but that's just a single flat number (perhaps return at different time windows like 1y or 30d would also be instructive). We'd like to have something like Metaculus's calibration chart aggregating info from each trade placed or market set up; if anyone has ideas here, let me know!

Anyways, your commitment to bet on your beliefs really makes you stand out among the many political commentators out there. I hope that this post encourages your readers/colleagues to do the same!

It’s strange that people say you can’t reinforce fertility by money, when our whole civilisation functions by forcing people do what they don’t want by money incentive. Lyman Stocke gives example of Germany who gives 25$k per birth and raised fertility for 0,15 with it. But 25$k per birth is just 0,5% of yearly gdp. Why not throw something like 5%? Countries sometimes spent 5% of gdp or mire on defence, 10% or more on pensions. And fertility is important both for defence and (future) pensions and other questions aswell. If question is important 0,5% of gdp is not enough.