How to Think about the "Current Thing"

Deciding in which direction you want people to be sheep

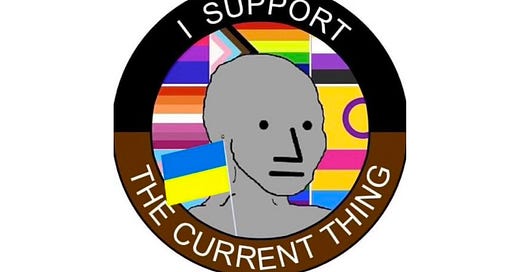

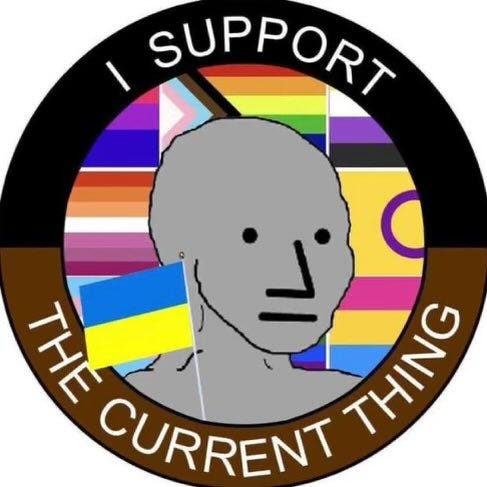

Once in a while in these troubled times we get a meme that meets the moment.

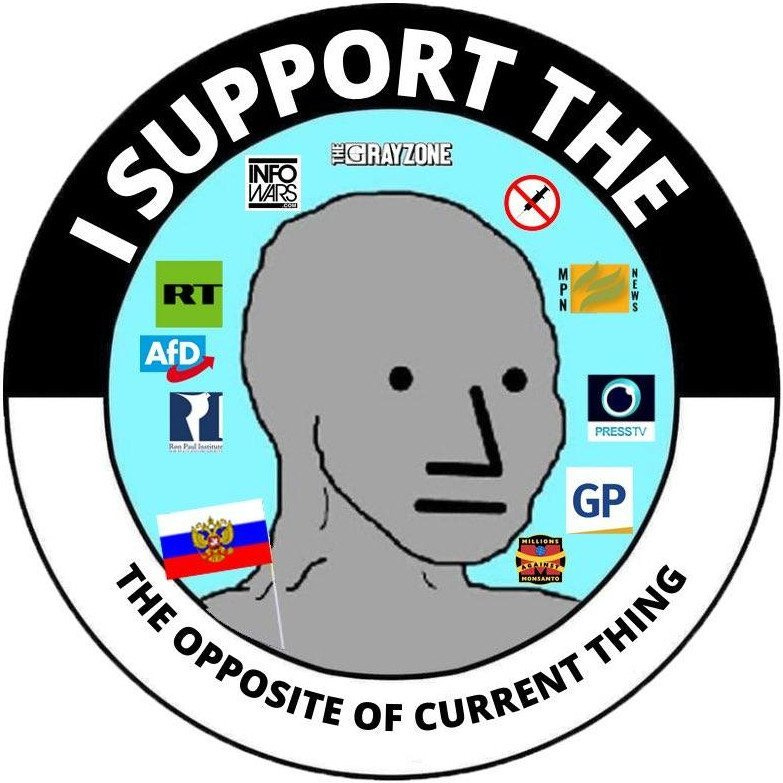

Of course, social media being the force for clarifying the terms of debate that it is, we also have a rebuttal.

As is often the case, these memes have taken off because they reflect something that’s obvious and clear from our current moment. It’s difficult to see an ideological connection between supporting child soldiers in Ukraine and putting American children in a bubble out of fears of COVID, but somehow many of the same people seem to support both. On the other side, there is no obvious link between being skeptical about vaccines and global warming denialism, but the two do seem to go together. It’s not “anti-science,” as we can see by thinking about which side accepts the reality of sex differences.

So which guy should you be? The seemingly obvious answer is “neither one, I will apply my critical thinking skills to each issue.” That would’ve been my position a year or two ago. But I’ve come to believe that this approach is unrealistic for most individuals and hopeless in the political realm. One thing I find odd about the anti-SJW crowd, say your median contributor to Quillette, is that they seem to believe that IQ is real and important and also that normal people with average IQs can be expected to think for themselves and reach reasoned conclusions about economics, geopolitics, and epidemiology. But the truth is you’re not going to be able to teach “critical thinking” in schools, so you might as well decide in which direction you want people to be sheep.

If one is going to have political views and encourage others to support certain movements and oppose others, one has to realize that all of them operate according to a handful of rules. There is no such thing as a political movement large enough to be effective that is also composed of free thinkers. In modern America, the current thing tends to be associated with the left, and anti-current thing with the right, particularly populists. Having a generalizable attitude towards the current thing can help an intelligent person decide among other things who to vote for and which party represents the lesser of two evils.

Moreover, even the smartest and most independent minded among us don’t have time to research everything and must start with certain priors. Let’s say you’re an intelligent person who in late February knew nothing about Russia, Ukraine, or American foreign policy. Which websites should you read to become informed? You notice that many sources seem to always take the “current thing” perspective, while others have the opposite bias. There are only so many hours in a day, and the judgment calls one must make in researching an issue are too numerous to list. Are those whose first instinct is to trust and promulgate the dominant narrative the most or least reliable sources of information? Given enough familiarity with an issue, an individual should be able to calibrate his views on it, but priors have a role in telling him where to start, and can determine which conclusions he reaches in situations where there isn’t enough time to thoroughly study a topic.

Simple heuristics are unavoidable. It is up to us to decide which ones we should prefer. That being said, I would argue that a probabilistic approach suggests that we should be anti-current thing.

Public discourse tends to be dominated by one issue at a time. There is often one topic that even individuals and institutions that are usually apolitical become expected to take strong stands on. This is the “current thing.” After 9/11, it was terrorism and Middle East wars for a while. Public attention to shootings of young black men kicked off with the death of Trayvon Martin in 2012 and George Floyd is just the latest in a long series of these cases. For a few years at the start of the Trump era, “white supremacy” somehow became the most important thing in the world as minorities started shifting a bit towards Republicans.

COVID-19, trans bathroom bills, and #MeToo were also current things. Controversies over topics like abortion rights, “kids in cages” at the border, AAPI hate, global warming, and school shootings and subsequent calls for gun control have been “mini-current things”; they have the ability to dominate the news cycle for short periods of time but don’t bring out the intensity we saw in, for example, the George Floyd protests. The current current thing is of course the war in Ukraine.

Let’s say that there are 50 issues at any one time the public could be paying attention to, and we can rank them objectively from most to least important. The most important issue should get the most attention, the 17th most important should get the 17th most attention, etc. When something is the “current thing,” it means that society is treating it as if it is the number one issue. But if the process that decides what becomes the current thing is somewhat random – i.e., current thing status is uncorrelated with importance – then there will only be a 2% chance that we are prioritizing it correctly, and a 98% chance we’re overestimating the problem.

But is it random? Is there any correlation between how important something is and whether or not it attains the status of current thing? At best, there seems to be a weak one. COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine are pretty important. But terrorism, white supremacy, and police shootings of black men are such tiny problems in modern America that if we were a logical society we would all but ignore them. Something like the process of aging, a major tragedy every human is experiencing every moment of their life, isn’t even considered a problem that policy should try to solve.

Moreover, being into the current thing usually implies not only thinking about the current thing, but following the crowd with regards to how to approach it. That means for the current thing bias to be correct, one has to not only believe that elite discourse has its priorities correct, but that its solutions are also correct, and are better than doing nothing. COVID-19 was worth worrying about, but most non-pharmaceutical interventions almost certainly did not pass a cost-benefit test. Thus, even though society was correct to prioritize COVID-19 as perhaps the most important issue of 2020, we still overreacted to it. Or more precisely, we underreacted in terms of not being even more active and decisive on the production of and investment in vaccines, but overreacted with regards to every other question surrounding how to deal with the problem.

Finally, when an issue attains current thing status, it is not simply that we treat it as slightly more important than other things. There is a step change between being a current thing and not being one. For the sake of argument, say that in 2020, COVID-19 was objectively the most important thing in the world and climate change was second, and that was approximately how the media judged the importance of those two issues. That didn’t necessarily mean that COVID-19 was only going to get slightly more attention than global warming. Instead of getting something like 20% more attention, which may have been the correct approach, it was more likely to get something like 5 times more. In practical terms, something being the current thing means it is treated not only as the most important issue, but in many ways almost as if it is the only issue in the world. This is my impression from observing how public discourse works. The costs of COVID-19 and the costs of lockdowns have both been investigated and discussed over the last few years, but the former have received orders of magnitude more attention even when we’ve been talking about children, the demographic for which the latter are clearly much higher.

This means that even if you trust society to get its ordinal preferences right, it’s likely overreacting to whatever it considers the most important problem at the moment.

Social media appears to be making this tendency worse. Parents who never thought twice about the flu but are worried about their healthy toddlers dropping dead of COVID are now able to find one another, along with credentialed influencers who appeal to their worst fears. Politicians, journalists, and others that are part of the discourse are radicalized by and responsive to such influences. Those that never thought about Yemen want to start a nuclear war over Ukraine. Emotions are getting more extreme, and the more an issue happens to engage a disproportionate share of the attention of neurotics the less we are able to approach it in a rational way.

None of this is to endorse a knee-jerk contrarianism that calls for people to adopt views that are mirror opposites of current things. Being anti-current thing in a healthy way in the conflict over Ukraine does not mean supporting Russia but being skeptical of the narratives seeking to justify American involvement and being able to approach the issue without the hyper-emotionalism that has become the norm. It doesn’t mean denying COVID and global warming exist, but starting from the position that whatever solutions being proposed for these problems are likely ineffective or go too far. The likelihood that the dominant narrative is centering the most important issue and proposing the right solutions in any particular case is vanishingly small. The only recent example I can think of when this has been true was the media calling for more vaccinations to deal with COVID, and even in that case the same people that did so tended to support mask mandates and other NPIs. Almost all recent current things have been either fake problems (terrorism, police shootings) or real problems where hyper-emotionalism has made rational thinking impossible and our policies have been likely to do more harm than good (Ukraine).

All that is fine with regards to approaching issues from an intellectual perspective. In the realm of politics, however, I’m inclined to go even further in taking an anti-current thing position. Here, you often have to choose between movements that are pro-current thing (“trust the experts”) and the aforementioned knee-jerk contrarianism that is unhealthy in an intellectual but in practice can make for relatively sound policy. If your model of the world says that modern society has a strong tendency to overreact to the issue of the day, you might prefer your leaders to have purely reactive instincts if such figures are the only alternative to the side associated with the establishment that decides what the current thing is in the first place through what is clearly an extremely flawed process. I’m not saying this is the high-IQ case for Trumpism, but it does point in the direction of what it might look like.

Of course, I advise you to think for yourself, seek out objective evidence, and proceed with intellectual humility. But if you’re going to be involved in politics at any level – from voting to campaigning or running for office – we all have to choose what movements, political parties, and programs to support. We also have to decide which priors we should start with when consuming new information and incorporating it into our worldview. As far as heuristics go, “oppose the current thing” is probably pretty good as long as it’s not the only one you’re using. It is more certainly better than the alternative.

A better approach is to mostly ignore “The Current Thing” because for most people being obsessed with current news is unproductive and unhealthy.

I'm a contrarian myself (which maybe is why I'm arguing the contrary view here), but....

One should generally be sympathetic to the "current thing" and here's why.

1. Be sympathetic. Any current issue can be addressed sympathetically and from whatever political/philosophical perspective you come from. Like, I tend to be a conservative libertarian. The whole point of why I think this is the correct view is that it's the best answer to most social problems. That means I can give a sympathetic response on any issue. Even if it's a contrarian one about the means of fixing it.

2. If you want to have influence, the worst way to do it is to shut off discussion. This is one of the biggest problems with Wokeism as a culture. Every discussion tends to be started with a statement of perspective "as a white/black/gay/straight/liberal/conservative/man/woman/transgender/salamander..." that is, I think, designed to preempt the discussion itself by giving cues to control thought. The best way to avoid that is not to play.

So, it's not always possible, but I find that it's usually quite possible to make a "libertarian" or "conservative" case for most every subject. What's more, if you don't say it's "conservative" or "libertarian" to start out with, and just say, "here's a way to help Group or Situation X" many people will unexpectedly agree with it.

By combining these points, one gets to be part of the discussion rather than standing outside it harrumphing that nobody listens to you.

Another way to put it is that when sensible people cede the floor to extremists and loudmouths, this is what you get. Taking your ball and going home isn't an answer.