Given that I’ve made quite a few predictions about the war in Ukraine and how it would unfold, now is a good time to look back on them and draw some lessons. My record is mixed, having predicted that the war would happen but being, so far, mistaken about how strong Ukrainian resistance would be.

Before getting to that, it’s worth going back to how I thought about the fall of the Afghan government. Last May, I gave a 55% chance that the Taliban would take Kabul by the end of 2021. Metaculus was giving the same event a 60% chance of happening by 2026 up until a week before the city fell. Even that estimate was high relative to the impression one would have gotten from reading foreign policy experts, who are not as smart as the Metaculus crowd, which is why Biden embarrassed himself by promising that the government could stand on its own, at least long enough for Americans to get out of Afghanistan and forget they’d ever been there.

My logic was simple. The Afghan government had the strongest military in the history of the world subsidizing it and fighting on its side, and it still had been losing territory for years. Once that support was removed, the whole thing would prove to be a house of cards. The old regime had the trappings of government: a parliament, cabinet ministers, a seat at the UN. It had press conferences, and American generals went before Congress singing its praises. It even had a law criminalizing sexual harassment. None of this meant it could fulfill the basic functions of statehood. It’s incredible to think that the US could sacrifice so much blood and treasure and have so little to show for it. But the fact that the Afghan government was losing even with American support should have led one to discount other kinds of information supposedly relevant to what would happen after US withdrawal. Even though I had studied the conflict pretty closely, it didn’t require much additional knowledge on top of that fact to predict the eventual outcome of the Afghan Civil War. The only reason I didn’t think the odds of collapse were even higher was due to the political uncertainty involved, as there was no way of knowing whether Biden would stick to the withdrawal plan regardless of circumstances.

My reasoning was similar when it came to thinking about a potential Russian invasion of Ukraine. I thought that there were difficult realities others weren’t facing, namely that Russia had overwhelming military power over Ukraine and it was in a tough security situation due to NATO expansion and deepening military ties between Kiev and Washington. Probably overlearning from Afghanistan, I thought an American client state without a strong conventional army of its own would fall relatively easily. I therefore predicted the Russian invasion (correct) and a quick collapse by the Ukrainians (wrong).

It was in early December that the American media started reporting on a Russian troop buildup on the Ukrainian border that journalists and US intelligence officials claimed could be the precursor to a massive military offensive in early 2022. While many who are skeptical about US foreign policy as a general matter weren’t buying the intelligence, the following three articles made me believe that something serious was probably going to happen. They’re each still worth reading for understanding how we got to this point.

Adam Tooze. January 12. Putin’s Challenge to Western Hegemony. Making the case that Russia was getting ready for conflict and explaining recent developments in Ukraine towards joining NATO.

Rob Lee. January 18. Moscow’s Compellence Strategy. Explaining developments in military technology and why Russia had good reason to think that if it did nothing Ukraine would be better able to defend itself in the future.

Anatoly Karlin. February 15. Regathering of the Russian Lands. A Russian nationalist perspective, which helped me understand the human capital case for seizing Ukraine, which might have appealed to Putin. Also made a convincing argument that going halfway – i.e., recognizing Donetsk and Luhansk and stopping – would have been the stupidest policy of all.

Assuming that Putin was a rational actor, together these articles made a convincing case that he would go to war and he would go big.

I had written on why I thought there wouldn’t be an insurgency in Ukraine, which if my arguments were sound would have removed another reason why one might have expected Russia to think twice before invading. People talk about the American and Soviet wars in Afghanistan illustrating the dangers of occupation, but I thought this would be more like Syria, where Russia succeeded because it had effective partners on the ground, was willing to use as much force as necessary, and did not try to engage in social engineering. My thinking was that this wasn’t a US invasion, where troops are sent to the other side of the world to build girls’ schools for 20 years and form an entirely new society among people they know nothing about. Russia would be replacing a pro-American oligarchy with a pro-Russian one, either through installing a puppet regime or outright annexation. And it would be fighting to win a war, not provide jobs for NGO types or give politicians sound bites. That was my thinking at least, and this theory turned out to be mostly wrong, at least in its more extreme form. But it looks like Putin might have bought into the same logic, which is why he has invaded Ukraine and made some otherwise puzzling decisions along the way, like not fully utilizing his advantage in the air.

I started posting my predictions about the likelihood of an invasion by the end of 2022 and comparing my forecast to the median at Metaculus. Here is the thread. Starting at the beginning of the month, I was consistently around 10-20% above other forecasters.

Feb. 2: Metaculus at 49%, Me at 65%

Feb. 16: Metaculus at 60%, Me at 78%

Feb. 19: Metaculus at 76%, Me at 90%

Feb 21: Metaculus at 83%, Me at 95%

I’m proud of my record forecasting the invasion, given that it went against most of the predictions of those who generally share my foreign policy views. Anyone can occasionally be correct by following the same heuristic they always use, but I showed intellectual flexibility here by determining that American intelligence was likely correct. Karlin is the only other prominent US foreign policy skeptic I know of who thought war was even more likely than the conventional wisdom suggested, and he deserves credit for that (if you know of others, mention them in the comments). Part of the reason I came to the right conclusion was that I was even more pessimistic than most anti-interventionists were about the degree of rationality present in American foreign policy. For example, my friend Max Abrahms was saying until very recently that Putin was hoping for some concessions that would allow him to avoid war (to be fair, Max has been more correct than me on the invasion running into difficulties). I thought that was possible too, but I had little hope that American politics would allow Biden to strike a deal. When it became clear that negotiating over the NATO open door policy wasn’t even on the table, I increased my estimate of the probability for war. To his credit, Max has admitted I was right, as have others I’ve been texting with over the last few months. I also give credit to Saagar, Philippe, and Michael Tracey for publicly acknowledging mistakes.

As I’ve said before, “trust the experts” and “don’t test the experts” are both bad heuristics (see the Substack article and its NYT version). Talking to anti-interventionists about the potential for a Russian invasion throughout January and February, I was struck by how often they would ignore my arguments and instead say things like “this guy has always been right, so I’m going to trust him.” That might be an adequate strategy when you have nothing else to go on, but here we had a lot of evidence relevant to what was likely to happen, including satellite imagery of military movements and reports on the state of diplomatic negotiations. I’ve found one of the most insightful analysts throughout the crisis to be Dmitri Alperovitch. But when I shared one of his tweets with a very intelligent friend of mine, his response was basically “his profile says that he is affiliated with Crowdstrike, which was involved in the Russiagate hoax. How can we believe anything he says?” I can understand the reaction, but it seems like this kind of thinking led many intelligent observers astray.

Regarding the prediction that there would be no insurgency, it is not technically false yet, since the conventional phase of the war is still ongoing, but I have to be honest and say that I expected a lot less fighting than we’re seeing. As already mentioned, I thought it might be like the fall of Kabul, where the weaker side just melted away even if it could’ve theoretically held out longer. But the Afghan government was probably uniquely bad, and the fact that it performed so poorly didn’t mean that Ukraine was a fake nation or that no one would fight for its government. A clue should’ve been that, although the Afghan government was losing territory even with American support, Ukraine had been doing an adequate job in its own defense since 2014 and holding its own in the war in the Donbas.

My argument that Ukraine did not have a high enough TFR to tolerate the casualties required for an asymmetric conflict may well have been motivated reasoning, based on my view that not having enough children is a sign of moral and spiritual decline. We’ll see soon enough if the view was well founded or not, as a Ukrainian collapse is still possible, even if it takes longer than I would have thought. Similarly, a source of wishful thinking here might have been my suspicion that, if there was a more sustained conflict, it would mean a great deal of Western involvement, which would raise the risk of nuclear war.

I also didn't anticipate the strength of the Western response. In part, this was because of how American and European leaders talked before the war. If you were going to cut Russia off from SWIFT, for example, why wouldn’t you announce it beforehand? The whole point of a punishment like that is supposed to be its deterrent effect, but if you don’t communicate that a specific action will happen, then it can’t influence behavior. The answer here seems to be a lack of grand strategy, with leaders responding to events according to emotion and public relations more than anything. Cutting off SWIFT, or even threatening to do so, seems extreme before an invasion occurs, but not after it has begun. This kind of irrationality is something I should’ve anticipated, given I wrote a book in which the main argument was that this is exactly how politicians behave.

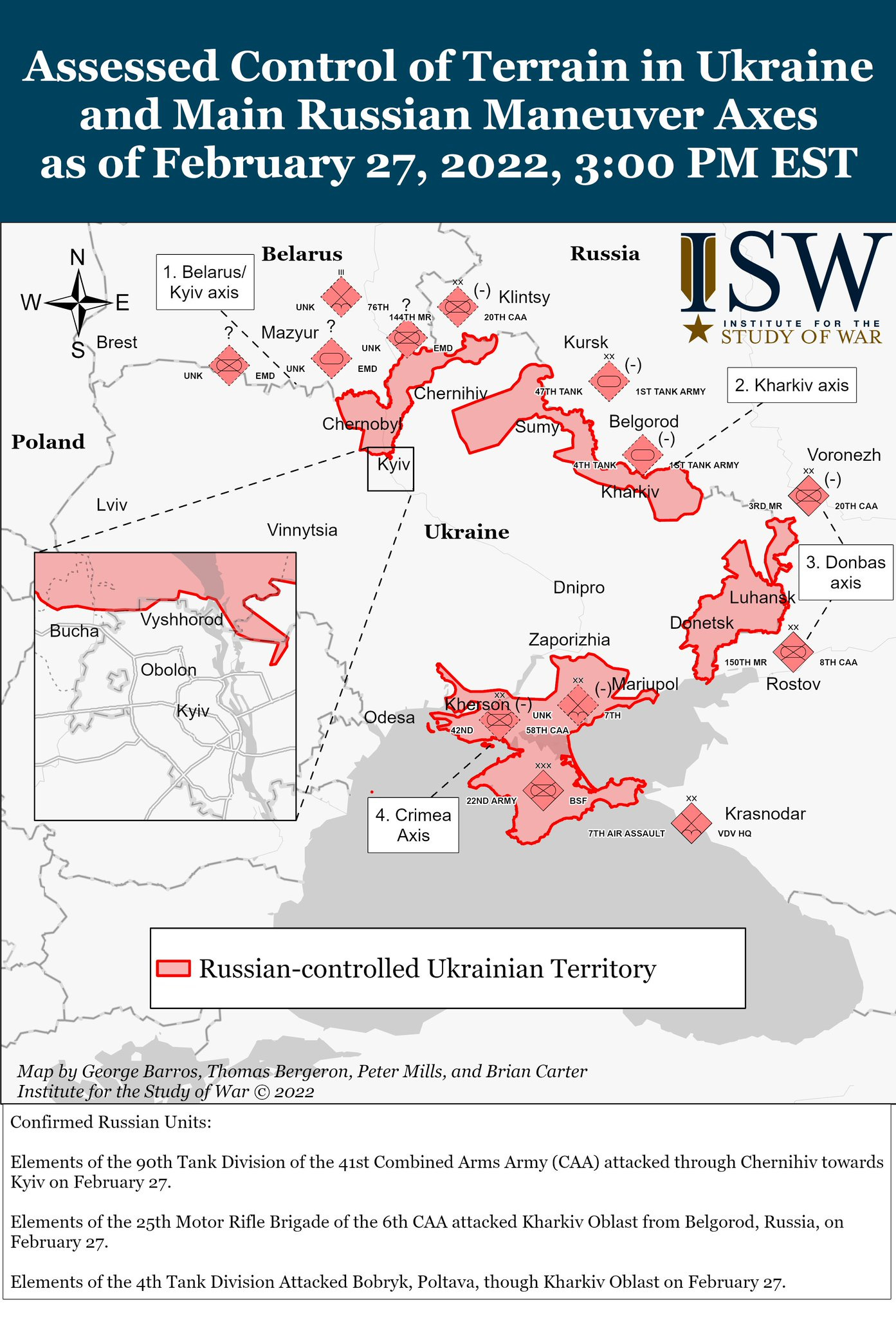

Now, we shouldn’t get ahead of ourselves, as Russia is still making rapid progress. It took the US three weeks to take Baghdad, and as I write this we are still less than 5 days into the invasion of Ukraine and fighting has reached the capital. This might still work out for the Russian government, if not its people, if it takes Kiev, is willing to absorb the economic fallout, and then potentially negotiates from a position of strength as the US and EU face their own economic problems resulting from high energy prices and retaliatory sanctions. But even a “successful” war is going to cost a lot more than I thought it would in blood and treasure.

For what I think is going to happen from here, I’m participating in the Ukraine Conflict Challenge at Metaculus and posting my predictions as time goes on in this Twitter thread.

On what actions the parties to the war should take now, the way to settle this conflict is still the same as it was before the invasion. Russia has security concerns, and Ukraine and the United States need to take them seriously. The only difference now is what we’ve learned since the start of the war, which is that the Russians are willing to take radical gambles and suffer large costs to address their concerns, and the Ukrainians can defend themselves and together with the US and Europe make the costs of military action even higher than anyone expected. Since neither side can be dictated to, now more than ever the answer is a negotiated settlement both can live with.

One potential problem here is that a no-NATO pledge is hard to make enforceable, and the same is true of any promise that Russia won't invade again. Yet if the two parties can make an agreement for the sake of psychology and public relations, each can hopefully trust that the other realizes how stupid it would be to try this again. I would guess that political considerations will make this outcome impossible in the short run, but eventually that’s the deal we’re probably going to end up with at one point or another. The sooner it happens, the better. As for the alternative, Metaculus gives a 4% chance of a nuclear detonation causing at least one fatality by 2024. I’m at 2%, but those odds are still too high, and getting them down should be the main goal of foreign policy.

One thing you didn’t predict, understandably, is the “Twitterization” of the conflict.

Suppose that you set out in 2019 to predict how governments would respond to the next pandemic. How would you do this? Presumably you’d look at their responses to past pandemics, estimate the probable severity of a virus, follow the latest public health discussions and the latest vaccine technology, etc. Would that exercise lead you to predict what happened over the last two years? No, not even close.

What happened was that people in early 2020 scrolled and tweeted their way into a frenzy. This deeply affected those in leadership roles, partly because they were responding to their constituents and partly because they themselves spend a lot of time scrolling and tweeting. As a result, the pandemic response was far more extreme and far different than someone in 2019 would have predicted.

Just as COVID-19 is the first pandemic in the Age of Twitter, so the Ukraine invasion is, in some sense, the first war in the Age of Twitter. As it unfolds, we are seeing many disturbing parallels to the events of early 2020. People are rapidly normalizing once-fringe ideas like a NATO-enforced no-fly zone, direct US conflict with Russia, regime change in Moscow, and even, incredibly, the use of nuclear weapons. Just as with COVID, we’re seeing the rapid abandonment of longstanding Western policies. The overnight flips on German defense spending and SWIFT are like the overturning of conventional public health policies on masking, lockdowns, and so on.

The emotionalism and recklessness we see in the Western professional class right now are producing an extremely dangerous situation. Let’s hope that it can be de-escalated before we get into a world war. And in making future predictions, we should acknowledge that the hyperconnected world brings with it new tail risks produced by rapid online escalation.

NATO expansion is a pretext for the deranged emperor to extend the reach of his mafia state. Historically, Ukraine was not a country, but Putin forged it. If Russia were attractive as a partner, many Ukrainians would support getting closer and perhaps establishing a confederation. But this is over now. The hatred against Russia is at the level not seen since the war against Nazis. If you could understand the pull of freedom and the disgust with Russia among the Ukrainians before the invasion, you’d have made a much better prediction about how strong they’d resist the invaders. Ukraine has already won since the now have a leader who, dead or alive, is a powerful symbol of resistance against the ugly force and the catalyst of national unity and readiness to sacrifice to keep national freedom. And plz stop talking about NATO expansion as the reason for this invasion and stop pushing for appeasement of the mafia state.