I read Bentham’s Bulldog’s recent article on Pascal’s Wager with some interest. The basic idea is as follows.

Let’s say your credence in Christianity is one in thirty-thousand. This seems pretty absurdly low—you should generally have a non-trivial credence in any view believed by a sizeable share of the smartest people who ever lived. Suppose that conditional on Christianity, you think the odds are 10% that believing it will increase your eternal reward. This still means that being a Christian has infinite expected value. It increases the odds of eternal reward by one in 300,000.

Presumably it would be worth performing some action if it gave you a 1/300,000 chance of infinite reward. If by working on reducing nuclear risks, you could lower the odds of the end of the world by one in 300,000, then that would seem like a valuable career, even if atheism is true. By conservative estimates, wagering on the right religion is better.

I’m not sure about this logic. I don’t know how to think about probabilities at the level of 1/30,000 or 1/300,000. At some point, these numbers cease to have meaning. A rule of thumb that says go through life just ignoring 1/300,000 probabilities seems like a good one to me. But putting that aside, I would give Christianity maybe a 2% chance of being true, almost exclusively on the grounds that a lot of smart people have believed in it, plus it was the faith of the civilization that conquered the world. Christian ethics has never made sense to me, nor have I found the alleged historical evidence for miracles or the Resurrection to be compelling. But I have enough intellectual humility to say that if many people as intelligent as I am have believed something, I’ll give it more than 1/300,000 odds, even if I’m pretty certain in my own opinion.

So the probabilities are high enough for me that it seems like I should take Pascal’s Wager. Yet something about this feels like extortion. Bentham continues:

Now, this is obviously correct as far as it goes. Pascal’s wager does not automatically tell you to wager on Christianity. Rather, it tells you to wager on whichever religion you think is likeliest. Suppose, that you think there’s a 10% chance of Christianity which requires you to believe it to be spared from hell, a 1% chance of Islam which requires you to believe it to be spared from hell, and a 5% chance of Hinduism that requires you to believe it to be spared from hell.

In this case, following the wager, you should believe Christianity because doing so minimizes the risks of you going to hell and maximizes the risk of entering heaven. There might be more complicated considerations—e.g. it might be that a single moment in Christian heaven is better than eternity in Muslim heaven — but barring that, you should just go with whichever one is most probable. You should take actions which make it likelier that you’ll spend forever in paradise.

Here, he glosses over the differences between religions in terms of what happens to one’s soul if you’re wrong, yet based on what we know about the world, they’re very important for how exactly we take Pascal’s wager. If Christians and Hindus both believe in hells that are about equally bad, then we can judge Christianity versus Hinduism based on the merits of each faith – that is, their moral and empirical claims. In contrast, if one religion threatens you with a much worse punishment if you reject it, then that should trump everything else.

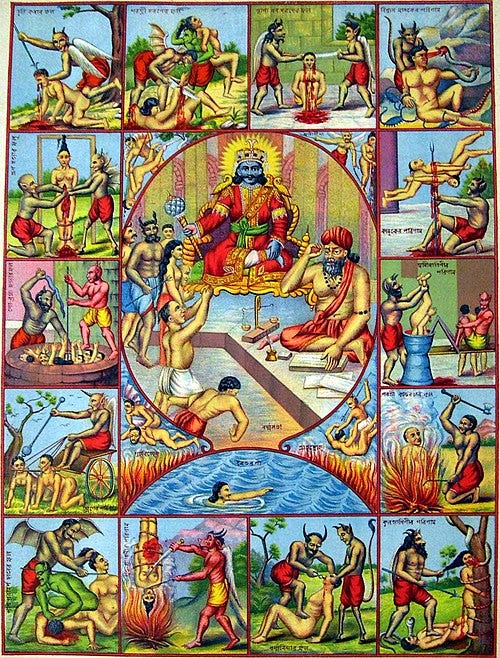

Bentham acknowledges this when he writes “[t]here might be more complicated considerations—e.g. it might be that a single moment in Christian heaven is better than eternity in Muslim heaven — but barring that, you should just go with whichever one is most probable.” The phrase “barring that” is doing a lot of work here. The mainstream Christian view has been that God tortures you forever. Hindus believe that you go to a place called Naraka, where you atone for your sins, but at some point the punishment ends. You basically get reincarnated until you achieve salvation. Screw up this life, no big deal, because you’ll always have another chance.

With this difference, the logic of Pascal’s Wager would say you definitely choose Christianity over Hinduism. The consequences of being wrong in the case that Christianity is true are infinitely greater, in the same way how under Christian cosmology our time on earth matters little compared to the afterlife. But the upshot here is that Christianity “wins” only because it promises by far the harsher punishment. Perhaps its only real competition in this regard among the major faiths is Islam, which likewise becomes one of the finalists for the religion you should choose based on how cruel it is towards unbelievers.

I’ve always been surprised by the lack of stress that intellectual Christians put on the issue of eternal damnation. It doesn’t seem to bother them that much, as I mentioned to Ross Douthat when I interviewed him. Imagine you heard about a foreign leader who took some portion of the population, put them in chains, and kept them alive for decades, torturing them for every moment for the rest of their miserable lives. This would be by far the most important thing about judging that leader. You would find his views on monetary policy or the tax code very uninteresting compared to that. Anyone who wanted to defend the regime would be asked to answer for the torture chambers first and foremost.

Why shouldn’t we see the Christian God the same way? The fact that he sends people to hell for all eternity is the most interesting thing about Christianity. I’m not against a vengeance-based approach to criminal justice, which is why I’m an enthusiastic supporter of the death penalty. But I wouldn’t punish people forever. Say, seventy years of torture seems enough to balance the scales for any earthly crime. What about the idea that God gives us free will and some will choose to be bad? Fine, don’t let them into heaven. Extinguish their souls, which they never asked anyone to create in the first place. Maybe give them the supernatural equivalent of a long prison sentence. But this everlasting torture stuff is completely contrary to every principle of justice normal people hold. And it’s not like the Christian God reserves this punishment for the evilest among us. All you have to do is not believe in him.

This argument works not only for comparing Christianity to other religions like Hinduism, but also for comparing different branches of Christianity. Pascal’s Wager suggests that, if you find most religions to be about equally (im)plausible, you should choose between the most vengeful sects. To take Pascal’s Wager seriously, one must ignore all the religions that show any degree of cosmic tolerance or mercy, and pick between the ones with the cruelest gods.

The role of Heaven, providing a carrot in addition to the stick, is less salient. I’m inclined to be risk averse with my soul. Would you take a coin flip, with one side giving you eternal bliss and the other eternal torture? I would probably not flip that coin and take the choice of obliteration instead. Torture is bad, and bliss is good, but torture forever seems more bad than bliss forever seems good. So for the sake of Pascal’s wager, I focus on the downside of being wrong. I’d probably take the coin flip at 80/20 odds, but even then I’d be quite nervous.

Judging religions based on the merits can be an intellectually stimulating and perhaps even noble exercise. But there seems to be something deeply wrong with accepting an argument that simply rewards God for his human rights violations. It feels like giving in to terrorism. You might not have any other reason to be a Christian, but it can still make rational sense to accept Jesus if you’re afraid of everlasting hellfire. I wonder if this was why Christianity and Islam were able to succeed in the first place. Death has been an all-encompassing concern for most of our past, and when hearing the case for different religions, quite a few people have probably reasoned that it is better to be safe than sorry.

Is this what all of human history was? One madman comes along and says “follow me, you get to live for a thousand years and eat meat every day.” Another follows with his own promises: “same here, but if you don’t follow me God slaps you around for a couple days before you get to heaven.” Islam’s promise of 72 virgins seems to have this ad hoc quality to it. And on the prophets go, adding new prizes or tortures, extending their duration, until one day there is nothing more to reward or scare people with. Societies settle on the religion that gives you either infinite bliss or infinite torture.

It makes sense to me that this is how we got Christianity and Islam. It’s a wonder from that perspective that Hinduism and Buddhism nonetheless have so many adherents. Maybe that adds to the probability that one of them is the true faith, since they had to get ahead without being able to scare people with eternal damnation. Hinduism and Buddhism are like the Asian male who got into Harvard. You know he had to earn it. If Christianity and Islam ultimately conquer because they’re the religions of spiritual extortion, should we want to help them along? India and most of Asia are below replacement fertility now, and African nations continue to grow, so in the long run it looks like the crueler religions are going to continue gaining ground.

Since I’ve said I believe that there is a 2% chance that Christianity is true, I guess there’s nothing wrong with calling myself a Christian based on the small chance that it will prevent me from being tortured forever. But if Christ really was a divine figure, I’m hoping that the vast majority of those who have believed in him throughout history have been wrong about what he has in mind for the ultimate destination of most of our souls.

I always found the idea of the 'Old Testament God' being vengeful and cruel and the 'New Testament God' being kind and merciful weird. The Old Testament God only killed babies and ordered genocides, while the New Testament God sends most of humanity to eternal torture, which seems much worse.

100% of all people before discovering electricity had the wrong belief about how thunders work. It's a terrible argument to base your probability of something being true on how many people believe in it.