Reflections on 2021

On the marketplace of ideas, wokeness as a symptom, books of the year, and "New Year's Questions"

For me, 2021 was a very good year. First of all, I’m publishing a book on December 29 called Public Choice Theory and the Illusion of Grand Strategy: How Generals, Weapons Manufacturers, and Foreign Governments Shape American Foreign Policy. Yes, it’s ridiculously priced, and this is because it was written back when I was an academic and that’s the way the academic book market works. Luckily, the Kindle version is still expensive but much more affordable. If you would like a review copy, just respond to this email or reach out through CSPI. Now that I’ve become (sort of) famous, I can get contracts with popular publishers, and future books will be at normal prices. I’ll write more about the book in the lead up to the launch.

My 2021 has been so good that it’s inspired at least one good conspiracy theory. I’m not sure what the theory is exactly, but it sounds elaborate.

When I originally saw this tweet, it gave me a chuckle. Where do people think intellectuals come from? Doesn’t everyone “come out of nowhere”? I mentioned this to a friend, and he said yes, but usually people are known in certain circles for a while before their work starts to get a lot of attention.

To be honest, I have been a bit surprised by how well my work has been received. I officially launched CSPI on November 30, 2020. With a measly few thousand Twitter followers at the time, the hope was to support my own work, while also finding the handful of people who I thought were the most interesting and important writers out there who might not otherwise be able to support themselves writing about social and political issues.

I stepped into public life with a few disadvantages. In addition to not really knowing anyone, I didn’t fit anywhere politically and wasn’t able or willing to pretend to, being anti-woke, but also extremely skeptical of the two main forms of resistance to it – right wing populism and what used to be called the “intellectual dark web.” I also have a passion for criticizing American foreign policy, not in the most delicate terms, and while these days it’s easy enough to denounce the excesses of the war on terror, to push back against anti-China rhetoric is really blowing against the political winds and seems to anger many of my fans without getting any corresponding benefit in the form of praise from anyone else.

Putting aside foreign policy views, my style of argumentation, use of evidence, and data literacy made me to a large extent more comfortable talking to liberals than conservatives. These differences were the theme of my piece Liberals Read, Conservatives Watch TV.

Nonetheless, as it turns out, while the marketplace of ideas mostly rewards partisans who are comfortably part of a political tribe, there is unmet demand for higher quality analysis, and I’ve been flattered to get support and attention from across the political spectrum. Bryan Caplan wrote that “what’s most impressive about Hanania is the absence of Social Desirability Bias.” This is one of the nicest compliments I’ve ever received, and what I thought would be a hindrance to my work getting attention has probably been a strength. Those who think they’re free of social desirability bias because they ignore the pieties of one tribe often become slaves to another. The best example of this in the past year is the anti-wokes who became anti-vaxx, and I can understand the pressures of audience capture on this issue in particular as my pro-vaccine tweets are the only ones that make people angrier than the ones on China. But I genuinely don’t care, and this seems to be a rare quality.

As I told Razib in a podcast at the start of the year, public discourse is like a party, in that who’s already in attendance determines who else shows up. In the 1990s, politicians were boring, and politics attracted mostly boring people, which made the entire discourse smarter. Today, the lines between politics, pop culture, and reality TV have all become blurred, and I think we’re much worse off; people whose energy would have once been focused on pro-wrestling now opine on the most important issues of the day.

This means that there are higher-order effects of any particular individual becoming “part of the discourse.” If you’re an intelligent, fair, and honest person participating in public debates, you’ll draw others who are similar. Likewise if you are a partisan hysteric for whom politics is a way to work through mental problems. I’m trying to improve the discourse both by bringing better people to the party, directly through support from CSPI, and indirectly by changing the conversation. To give a concrete example of this, in my essay Woke Institutions is Just Civil Rights Law, I tried to emphasize that many of the things people are concerned about have their roots in policies that can be changed. If you dislike wokeness but are more oriented towards solutions than simply having an outlet to complain about things, you may find little that’s attractive in the standard responses to the phenomenon, which involve either writing an endless number of essays preaching to the choir on why it is bad (the IDW response; have you heard men might be stronger than women? It’s been peer reviewed) or developing a tribal hatred of the left that gets channeled into weird directions like anti-vaxx and anti-China or whatever “owns the libs” (conservatism). This and other work like it will hopefully inspire other people who care about “boring stuff” like EEOC regulations instead of “exciting” things like AOC’s dress to become involved in politics as intellectuals, aspirants for office, and activists. I’ve been talking to a lot of people in conservative politics who say the idea of civil rights law as a cause of wokeness has been taking off (see the latest City Journal), and I’m excited to see what might be done on this front in the next few years.

At the same time, CSPI has provided support to those of a similar disposition. Eric Kaufmann’s report on political bias in academia appears to have inspired the founders of the University of Austin, and while I’m skeptical of starting a university because I’m skeptical of universities in general, I’m glad to see people trying things rather than complaining about them or focusing too much energy on reforming institutions that I’d argue are already lost. Philippe Lemoine’s work on COVID-19 has been absolutely brilliant and gotten a great deal of attention in the field and in the popular press, and will hopefully provide clear thinking about how not to overreact to this pandemic and others like it in the future.

On the health front, I lost about 40 pounds this year. I was always fat growing up, and reached about 210 as a teen, before a rapid drop to around 160 when I was around 17 (thanks “bullying,” which kids aren’t allowed to do anymore apparently). I’ve been yo-yoing between 160 and 210 my entire adult life, being skinnier when I was motivated to eat less, like starting a new job or graduate program, and getting fatter when I was comfortable in life. For the last several years, life has been good, so I’ve been closer to 210, but then I got three minutes on Tucker over the summer. I thought I did a good job, but my face looked very fat, and I decided that if I was going to have more TV appearances I was going to need to lose weight in order not to be filled with self-loathing. Now I’m at around 170, but unfortunately Tucker has not invited me back on yet, so maybe I will eat more ice cream in 2022.

Enough with meta-reflections on the discourse and personal stuff. Below is what I learned about politics and society in the last year, how my views have changed, my best books of the year, and questions for the new year.

Anti-Vaxx and COVID Hysteria

At the end of 2020, I had basically learned that markets are amazing, our politics is broken, and East Asia has a lot of state capacity. At the end of 2021, I mostly continue to adjust my priors in the same direction. When I was writing last year, it was only two months after it was revealed that we had vaccines that got the risk of hospitalization and death close to zero. Despite any mistakes we had made, I thought surely everyone would want whatever vaccines were available, and that governments would get rid of practically all COVID restrictions. Neither of these things happened; deaths remain high and concentrated among the un-vaxxed, children remain masked in much of the US, and in parts of Europe they’ve gone back to lockdowns. The effects of the vaccines we’ve discovered wane over time, but boosters still take care of the problem. I’ve become bored with COVID as a scientific issue; this is an easy policy problem. Yes to vaccines, no to everything else except maybe interventions narrowly targeted at the elderly, the sick, and those at unusually high risk (see thoughts here and here). When something like Omicron pops up, I do enough research to confirm that it’s still “tldr: vaccines are good, life goes on,” and no longer look closely at every debate like I did at the start of the crisis.

So while the science of COVID isn’t as interesting – except when Philippe uses epidemiological models to highlight problems with “science” more generally – it still continues to concern me as a political and sociological issue, as I’m struck by anti-vaxx as a powerful political movement on one side and COVID hysteria on the other.

I’ve seen people say things like “what are you still worried about, the US isn’t doing lockdowns anymore.” While that’s true, this only seems like a victory for freedom because of how much we’ve shifted the goalposts. Mask requirements are a huge infringement on personal autonomy; at the height of the war on terror, people would say stupid things like we have to fight so our daughters don’t have to wear burkas. While this particular argument was silly, there was a widespread understanding that mandatory face coverings are an assault on a person’s identity and make normal human interaction much more difficult. That’s the entire reason why religious conservatives favor it, as they make men and women less likely to socialize and have premarital sex. Now, in schools, in many jobs, and in some places, whenever you’re indoors, we require both sexes to cover their faces, and we should not normalize this as a “low cost” intervention and feel grateful that at least they’re not locking us in our houses. While it’s hard to quantify how much of things like rising overdose deaths is due to the pandemic itself and how much is due to our overreactions to it, given our evolutionary past you should start with the prior that “face-to-face interaction is really important to normal human development and well being.”

Conservative anti-vaxx sentiment in the United States will surely end up having an absolutely massive death toll. Yet I’m not going to play the “both sides” game. A political movement that leaves people alone to make awful medical decisions and panders to anti-vaxx sentiment can have devastating consequences, but it’s compatible with some form of human life as we remember it before 2020. COVID hysteria isn’t, and we’re now in a world where there are kids who have spent half their high school or college years behind masks. I’m not an absolutist on such things; forced masking can be justified in cost-benefit terms, but given the absence of strong evidence that it has a major effect (again, read Philippe), it has to be considered a major human rights violation. I don’t want to hear about how Russia is bad; like any reasonable person, I care more about being able to show my face in public than being able to vote for a Congressman. If we get another pandemic that’s ten times as bad as COVID, conservative flirtations with and appeals to anti-vaxx sentiment might become the greater evil, and maybe we’ll actually have to cancel childhood. For now, we need saving from the lunatics on the other side.

One has to take people as they are, and it seems “vaccines good, masks and shutdowns bad” is just too complicated for most. People only understand two ways of facing a problem, which is freak out about it and try to do everything or don’t worry about it and do nothing. This is a good case for being a libertarian; while you might want government interventions that are likely to have a positive impact, in reality government will either be activist or passive, and passive is generally better because, like in any complex system, there are always more ways to interfere destructively in an economy than to interfere in a positive way. Almost no leader of any developed state has consistently accepted a line of “pro-vaxx, anti-everything else.” Trump was among the closest, and this to me redeems any other flaws he may have had. COVID hysteria has been such a destructive force that I’ve become much more tolerant of whatever forms resistance to it takes.

Wokeness as a Symptom, Not a Cause

The two places that have been most hysterical about COVID-19 have been universities and schools (see Michael Tracey). This was always crazy given the age distribution of the victims of the disease, and it has become even crazier in an age of vaccines. Before, I considered wokeness more as an ideological issue than one of mental illness. People had certain intellectual commitments, like disparities are caused by discrimination, and then did things that made sense given their false priors. Now I see mental illness as the horse leading the cart of ideology. Universities and schools are the places least objectively threatened by COVID, so their overreaction to the disease has to be understood as psychological in nature. Zach Goldberg has confirmed the connection between left-wing political views and mental illness, an idea that I used to see as a conservative troll but now appears to be strongly backed by data.

While wokeness can be attributed to ideology, there was no ideological reason why universities had to go all in on COVID restrictions. The view held by Jonathan Haidt and others that much of politics can be understood by the fact that conservatives are more afraid of germs has probably fared worse than any other idea in the social sciences over the last two years. Wokeness to a large extent involves submitting to the noisiest and most disturbed activists, or even adopting their views as one’s own, which people high on conformity are more likely to do. The overreaction to COVID can be understood similarly. By drawing in a large share of both conformists and mentally ill activists, colleges are breeding grounds for hysteria and submission to it.

Though one might suspect that neuroticism is playing a large role here, we don’t have to dwell too much on which forms of mental illnesses are higher on the left. Robert Plomin told me that the latest genetic research reveals a common p factor, where people who have one mental disorder are more likely to be prone to others, in the same way that the discovery of the g factor shows that a person who is good at reading is likely to be good at math or any other subject. Understanding mental illness as a fundamental division between the right and left is not only consistent with self-reported data, but can tell us why the same institutions go most overboard in their responses to both hurt feelings and contagious disease.

If I’m right, then if somehow you cured the universities of wokeness, they would find something else to be hysterical about, because they happen to be places where you get a large collection of unhappy and disturbed people – emboldened by a false sense of superiority and a lot of time on their hands – living at taxpayer expense free from the responsibilities that result from responding to market pressures or facing any other tangible forms of accountability. Public schools have a different dynamic, where it is the teacher’s unions and education bureaucracy that are composed of and influenced by the same kind of activists that play a prominent role on university campuses. If it wasn’t for wokeness, the people who determine policy in public schools and universities would still need somewhere to direct their energies. One can imagine them turning in a more committed direction towards socialism or extreme forms of environmentalism hostile to economic growth, which would probably be worse for humanity.

Fear of course has an evolutionary purpose. Again, if COVID killed 50% of the people who got it, you might hope liberals were in charge, although it’s likely that even conservatives would support vaccine mandates in that case.

The practical lesson of such an outlook is that the ultimate problem with universities is less the ideas than it is the people. This means one should focus less on curing them of bad ideas, and more on decreasing the influence of universities by getting fewer people to go to college in the first place and lowering the status of these institutions.

Best Books of the Year

See best books of the year for 2018, 2019, and 2020. I’ve realized that I have a lot of good Twitter threads on books, and they could disappear one day. If anyone knows how to archive them, I would consider it a personal favor. They apparently disappear from the thread reader app site if the tweets are gone.

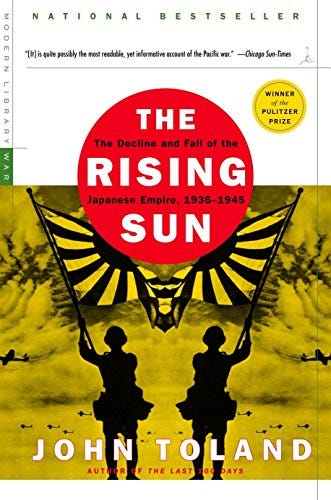

In the past, I have read so much on the Eastern front that it took up time that would have probably otherwise been spent reading about the rest of World War II. Stalin and Hitler fighting to the death, what could be more interesting than that? The War in the Pacific certainly compares, having been fought across awe-inspiring distances, from Burma to the Solomon Islands to the Aleutians under nightmarish conditions. On this topic, I’ve been riveted by John Toland’s The Rising Sun, which won the Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction in 1971 (thread). The naval battles in the Pacific were unlike anything the world had seen before or will likely ever see again, with large clashes between aircraft carrier fleets in the sky, on land and at sea. They depended on great powers fighting across a wide ocean in a very specific technological context, after planes partly reached their potential as weapons of war but before nuclear weapons, missiles, satellite technology and airpower could absolutely overwhelm naval force.

The politics of prewar Japan is another fascinating part of the story covered in the book, as is the long-forgotten motivation of its war against the US and Great Britain as a racial struggle to free Asia, an idea that seems absurd given Japanese treatment of foreigners but was taken seriously by many at the time.

I didn’t neglect the conflict in Europe entirely in 2021, and still read Stalin’s War by Sean McMeekin. Of all the books on Stalin, this is probably my favorite. I interviewed McMeekin on the CSPI podcast, and you can find a link to that discussion here. Steve Pinker is always worth reading, and this year he released Rationality, which I interviewed him about here.

Christopher Clark’s The Iron Kingdom made me wonder what could’ve been had Germany pursued a different foreign policy in the first half of the twentieth century (see thread). Like China, its development provides a different model that should lead us to question narratives about the historical inevitability of democratic capitalism.

Speaking of China, much of my reading this year has focused on the history and politics of that nation. As I’ve sought to learn more, I’ve noticed that most of the work that appears in the popular press is truly awful, marred by Western ideological commitments and the need to believe that things can never be that good, and that any country that is not a democracy must have some fundamental internal contradiction that will eventually lead to its collapse. Another problem is what appears to be an American need for a new enemy, motivated by psychological factors and the economic interests of the military-industrial complex, now that people are no longer afraid of Muslim terrorism. This leads to wild exaggerations about Chinese aggression in foreign affairs, something that I’ve written about, along with David Kang of USC.

Nonetheless, though good work is hard to find and doesn’t usually get the most attention, there are some gems out there. Here are the most valuable works that have helped me understand China in the last year.

How China Escaped the Poverty Trap (tweet) and China’s Gilded Age, by Yuen Yuen Ang.

Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China, by Ezra Vogel (see thread).

Mao: The Untold Story, by Jung Chang and Jon Halliday.

China’s Economy: What Everyone Needs to Know, by Arthur Kroeber.

Growing out of the Plan, by Barry Naughton.

Decentralized Authoritarianism in China, by Pierre Landry (thread).

Governing China, by Kenneth Lieberthal.

The Party, by Richard McGregor.

AI Superpowers, by Kai-Fu Lee (thread).

I also enjoyed John Keay’s China: A History, which doesn’t tell you much about the country today but provides a great deal of context and is beautifully written (thread).

I’ll be writing more on China in the coming year, as I think that we are fundamentally misunderstanding the most important geopolitical issue of our time. Not only are we not doing a good job of calibrating whatever “threat” the country poses, but we’re failing to learn from what has been arguably the greatest economic success story in human history at a time when our own institutions are failing miserably.

My views on civil rights law and wokeness were shaped by Frank Dobbin’s Inventing Equal Opportunity. He’s no conservative, as far as I can tell, but this is easily the best book I’ve read explaining how we got from 1964 to where we are today.

Two important books on Afghanistan that I read this year were No Good Men Among the Living by Anand Gopal (thread) and The Afghanistan Papers by Craig Whitlock (Reason review). On the history of the movement that once again took over Afghanistan in August, I learned a good bit from a 2010 book called Taliban by Ahmed Rashid (thread).

Other works that made an impression on me:

1177 BC, by Eric Cline (fascinating history, but found the attempt to connect it to modern globalization beyond silly).

The Great Stagnation, by Tyler Cowen.

The Stupidity of War, by John Mueller (interview here)

Nixonland, by Rick Perlstein (thread).

Woke, Inc., by Vivek Ramaswamy (American Affairs review here).

The English and Their History, by Robert Tombs

Crazy Like Us, by Ethan Watters (thread).

“New Year’s Questions”

I don’t like New Year’s Resolutions, because if you’re going to make a categorical rule to do something, you should do it now. So I’m going to invent a personal tradition that I will call “New Year’s Questions.” These are things that don’t have an easy answer, so they’re worth pondering at this time of year.

Should I spend less time on Twitter?

The most common feedback I get when meeting new people is “I love your Twitter.” The second most common is “I love your Substack, but I hate your Twitter.” I enjoy being on the website, and don’t think it takes away much from my larger projects. It mostly helps, because I meet new people with similar interests. Moreover, I actually find Twitter a good way to bookmark interesting things I’ve read that I might want to go back and look at later, as I do with the book threads. At the same time, I may only be getting the positive feedback, and perhaps people who really dislike me for Twitter are not saying anything (unless they like my Substack, which gives them a more polite way to discuss what bothers them). Anyway, as good as Twitter is, I should probably spend less time on it.

When I’m on Twitter, how rude should I be?

I tend to admire thinkers who are civil and think less of those who are rude. Usually, I try to emulate those I admire and not those I don’t, but I actually think there’s an intellectual case to be made for rudeness and snark as long as it’s used in defense of worthy ideas instead of tribalism or self-aggrandizement (maybe a topic for a future Substack). One thing that used to bother me about academia was how someone would have a critique of a research project that completely discredited it, but nobody would actually follow the argument to its logical conclusion and say the research was therefore worthless and the author should go do something else. We as a society would be better off valuing being correct more and being civil less. Maybe you would ideally want both, but I suspect that there’s actually a tradeoff, as people who tend to be right about a lot are often jerks, and academics who are wrong about everything always seem to be complimenting each other for being stunning and brave (see #HighlightingWomen and #WomenAlsoKnowStuff). Economics is less crazy than other disciplines, and now there are female academics complaining that the field is too mean, which to me seems necessary to trim bad ideas. So I’m sort of a fan of incivility and rudeness, but also thinking carefully about how to make snark constructive (I’m aware this could all be motivated reasoning and I just enjoy insulting people). Another consideration is that people usually say that movements do better when they’re polite, so I may be harming the prospects of the views I advocate for. This always struck me as a belief rooted in social desirability bias, a kind of “nice guys finish first” philosophy. The woke are the most aggressive and least civil and tolerant political faction in the country, and they seem to have had the biggest political impact in the last few years. Trump supporters are the rudest people on the right, and they’re wining on their side. So why do we think civility is good for a movement? Like using Twitter though, this is one of those things where it’s easy to see the benefits while the costs are hidden. I do at least go out of my way not to punch down too much, by for example hiding the identities of people with small audiences that I’m dunking on. Unless they’re academics or journalists, in which case society gives them a special status as people whose job is (or should be) to tell the truth, so I don’t see it as “punching down” even if they have fewer followers than me. Much more can be said on socially responsible trolling, for a later time maybe.

How much should I focus on American foreign policy?

Much of my work has focused on American foreign policy, but with the new book being released I think I will have said much of what I wanted to say. It’s clear to me that America faces no actual foreign threats, but it does harm to people across the globe through regime change wars and sanctions, while raising the potential for a major war through interfering in disputes involving China and Russia. One can attack individual narratives that are designed to turn the temperature up, like “Russian bounties” or China “lying” about the initial spread of COVID-19, just like one could take the time to debunk every claim made about Saddam Hussein in the run-up to the Iraq War. The problem is not so much any individual narrative, but a system that needs to keep manufacturing enemies to justify large budgets and a need for purpose among elites in Washington; any individual debunking won’t matter (for example, see here, here, and here), as the military-industrial complex and circles committed to global domination can always produce propaganda faster than it can be shot down. So other than writing about the rise of China in the context discussed above, if I focus on foreign policy much in 2022 it will be in the sense of exposing what’s rotten about the system more than paying attention to current events, and also by taking a more philosophical perspective and perhaps making the case for “moral equivalence” between the US and other countries that are supposed to be “our adversaries.” This may change though if it looks like America might be crazy enough to stumble into a war with Russia or China, in which case I will focus more on that.

Will I do more to monetize my success?

There’s a website that looks at your reach and uses it to estimate how much you earn on Substack. It says I am making $8,000 a month. I can guarantee you I am making nowhere near that, at least from Substack. This is probably because while people have the option of donating, all my content is available for free as I prioritize influence and reach over money. Nonetheless, I’ve been thinking about perhaps providing some incentive for people to donate and am open to suggestions. I’m considering writing more about my personal reflections and experiences (“Living with Autism: From Weakness to Strength!”) and putting those behind a paywall, while everything relating to politics or social issues will remain free to continue getting as wide a reach as possible. Not sure if I want to spend time on this relative to other things I do with my time like write books, run CSPI and read about World War II, but it might happen.

Thanks to everyone who has read and appreciated my work in the last year, and particularly those who have provided support in whatever form. I would welcome any feedback you have in the comments and look forward to doing more of this in 2022.

I think people would be much more amenable to your critiques on US foreign policy if you also found ways to be critical of China and Russia. I'm not saying you should do so necessarily, because it's good to have strident, focused critiques of US foreign policy and the harm it has caused that isn't coming from the tankie left. But, it's an option if you're concerned with gaining more traction with your ideas about foreign policy, which you seem to be. Whatabout and Yeahbut are very strong reactions for most people to easily silo. On the other hand, any critique, even one qualified alongside critiques of US foreign policy, can and will be absorbed and weaponized to support US hegemony and warmongering. Or perhaps Russia/China really are generally unaggressive good faith actors who deserve to control territories around them because its their right as powerful nations and because they really really want those places.

But everyone knows China/Russia are massively powerful states with all the attendant baggage and mistakes and foibles, so it will strike most people as odd that you don't countenance any of that (yes, even if you are right that it pales in comparison to what the US has done over recent decades, but we're talking rhetorical strategies here). Maybe you think US foreign policy is so disastrous and so harmful that it needs to be uniquely targeted at the expense of just treating other powerful adversarial nations as abstractions, which, you know, fine, but then you just can't be disappointed in a broadly negative response to that. Relatedly, I personally can't tell what your more normative prescriptions for the global state of affairs ought to be--like much of the left when they talk about capitalism, it's reasonable criticism, but just that. Placing your critiques in a broader, coherent vision would likely lessen criticisms. I don't think most people get any sense of that vision from your tweets.

You do seem (pathologically?) drawn to the snark contrarian take, which is perfect for Twitter and which you've noted will rightly garner some admiration among those who are always worrying they care too much about what others think. It is a unique and useful psychology and it's good we have people like you because you do it smartly and you generally target what I think are the right things. I mean, you realize already these are good qualities to have in our current battlefield of ideas.

Ditch Mao: The Untold Story (or anything from those authors), no one takes that seriously. You're right that it's really hard to discern good information/reading on China (99% just don't know a damn thing and anybody who doesn't admit how little they know can be generally discounted). Even people who have spent years and years in the country will still analyze it poorly or find it impossible to overcome their ideological beliefs about democracy, human rights, liberalism, capitalism, development, etc. People in the China studies field, like all fields, are protective of their "expertise" and are critical of others who just read a dozen or so books (and can't read Chinese or haven't lived there) and then pontificate (because even doing that little will make you feel like you're in the 1%), so your China takes will likely continue to face criticism. Of course, most people in the China field are also generally critical of the CCP for a number of historical and ideological reasons and they won't be able to look past Xinjiang/HK/Taiwan as easily as you can considering how many come from or have family/contacts/friends in those spaces (well, the later two).

You're right though that there's a lot to learn from China and the typical media channels cover it ignorantly and ideologically (though I think you'll be pleasantly surprised once you find the right seams to dig deeper into on the academic side). I personally will look forward to your forays and attempt to wrestle with what China's rise means, or ought to mean, for the rest of the world--especially us in the decadent and decaying west. It cannot remain beholden to the experts. Generalists with an audience like yourself have to start trying to make sense of things and affecting opinion. You might enjoy the "reading the china dream" website if you're looking for a way to drink from the faucet more directly, though of course there is curation in terms of what is chosen for translation.

Your Twitter personality is fine, for Twitter. Your psyche and ego can only survive if you treat it like a warzone.

This comes across bizarrely parasocial, but your piece was reflective about yourself to the extent it sounded like you wanted feedback.

Re monetizing for supporters: This is something I think about a lot! As a creator, you have this fundamental tension between making your digital work as widely available as possible (after all, the marginal cost of distribution is zero), vs recouping your up-front costs (the time and labor going in to writing each post). It's shaped a bit like the problem of funding public goods, and I'm pretty excited by innovation in the crypto world eg https://medium.com/ethereum-optimism/retroactive-public-goods-funding-33c9b7d00f0c

Anyways I've seen a few different supporter incentives that work well for writers:

- Monthly open Q&As with supporters

- Exclusive Discord/Slack community

- Early access to posts (more common among serial web fiction e.g. chapters that come out 3x a week)

These also can do double duty by granting you faster feedback, or advance proofreading/typo checks.

And if you're interested in experimenting with new kinds of incentives: how about play money for prediction markets? At https://mantic.markets, we allow creators to set up and resolve their own prediction markets. One idea we had for tying the currency to something valuable was to partner with authors, granting their supporters e.g. $100 of currency for each $10 donated through Substack. They can then bet on questions like "Will Richard write more than 10 book reviews in 2022? If you're interested at all, let me know!