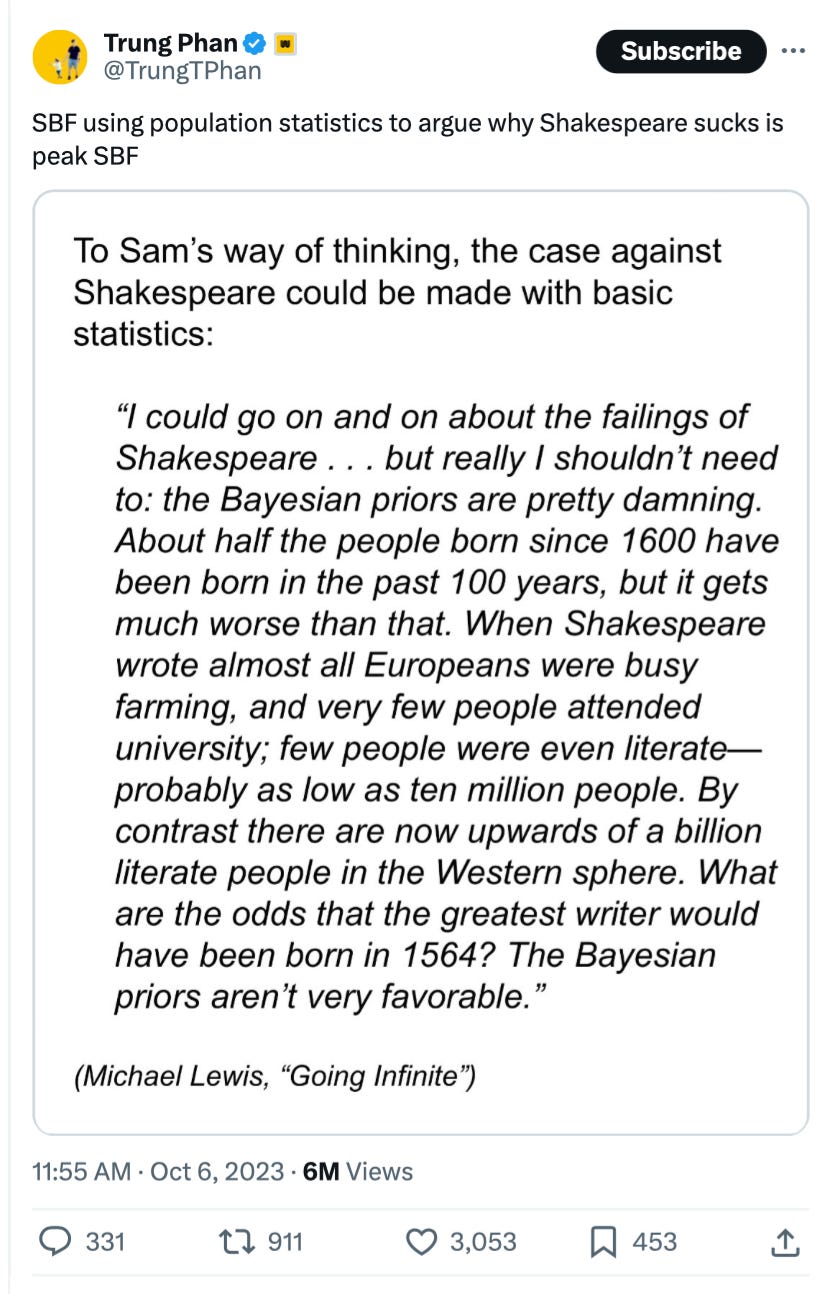

Sam-Bankman Fried has a take on Shakespeare.

It made a lot of people angry. But this strikes me as a very good argument, which I pointed out, and that of course also riled up a mob. I didn’t plan on getting into the Shakespeare discourse, but the Tweet on SBF kept popping up on my timeline, and it bothered me how people really weren’t engaging with the argument at all and simply appealing to authority and social conformity.

As Anna Gát has already pointed out, there are three ways we can understand the question of the “greatness” of Shakespeare.

Intrinsic: He produced the best plays and sonnets by some objective standard. This can be in an elitist sense focusing on the impact his work has on the most refined among us, or a more “democratic” one where the same can be said for all humans.

Relative: Shakespeare was great compared to those who came before him, or others of his time.

Generative: Shakespeare was the inspiration for a great deal of later work.

Part of the reason it’s hard to debate this on Twitter is that people will jump from one definition to another and we need to be careful regarding what we’re talking about. For example, when I said that I could copy Shakespeare’s style and produce something just as appealing, some people argued directly against the point, while others accepted my assertion but responded that Shakespeare would still be better than me because he did it first.

I won’t deny (2) and (3). But SBF was clearly talking about (1), so that’s what we should be responding to, and his argument here is irrefutable. The English population in 1560 was 3.2 million. Maybe 20% of them were literate at the time, so 640,000 individuals. Moreover, there are additional factors SBF doesn’t mention that argue against Shakespeare’s intrinsic greatness. People have a lot more leisure time now, so many more individuals have the option of trying to write something and seeing if they’re good at it. Moderns can flush the toilet instead of having to go empty their chamber pots. There’s also the Flynn Effect; we’re simply much smarter than people from the sixteenth century. Finally, Shakespeare had a lot less previous culture to draw upon. A few other factors might cut in the other direction. For example, if Shakespeare lived today, maybe he’d write Hollywood scripts instead of plays and sonnets, so the most creative artists are now going into different genres. But on balance it seems impossible that we’d expect fewer great writers today. And it doesn’t strike me that the pro-Shakespeare crowd would be satisfied if I said that Shakespeare is only the best writer because Vince Gilligan and Christopher Nolan aren’t bothering to produce poems, so this is something of a red herring. The economist Ryan Murphy makes a good case as to why we should expect better art and cultural products with rising GDP.

I think there’s an analogy here to the world of wine. We know from experiments that “experienced tasters generally can’t agree on which wines are better than others, or identify pricier wines as tasting better.” But if you slap an expensive label on a cheap bottle of wine, people will enjoy it more. Appreciation for complex literature seems a lot more subjective than what is felt by our tastebuds, and we see the degree to which the latter is influenced by external cues about prestige and quality.

The most annoying responses on X were along the lines of “we don’t need math, we can actually read Shakespeare and see how good he is.” This is the kind of argument made by people who are such sheep that they can’t imagine a non-sheep existence. Yes, of course that’s your perception. You’re a conformist, and you’re told that this is “great literature” and you accept that’s what it is just like you’re statistically likely to accept that Christianity is more logical than Islam. But that doesn’t make it true.

My claim about Shakespeare is this. Have a halfway competent writer study his style. Give that person a little time, and let them write a “Shakespeare like” sonnet. Find some smart readers who aren’t familiar with all of Shakespeare’s work and give them either fake Shakespeare or real Shakespeare to read. I’m sure that our imposter could produce something that ends up rated just as good, and that people’s judgments would depend more on whether they were told something was by Shakespeare than if it actually was.

And yes, I’d be happy to test this theory myself. If someone wants to do this study with me, reach out. Maybe if you’re a psychology or economics professor, you can conduct the Hanania v. Shakespeare experiment on your students and see what happens. This of course is the “hard version” of my argument. Ideally, you’d get someone who has written fiction before, but my claim is more extreme and I think that anyone who can write decent prose on any topic can do it.

James Miller argues that I couldn’t fool his wife, who is a classics professor. I grant that someone who knows Shakespeare well and has internalized standards based on what Shakespeare wrote will judge him a better poet than me, in the same way that an expert in Hananiaism could point to distinct reasons why my essays are the best. The real question is whether Shakespeare is intrinsically great outside the world of Shakespeare experts. We don’t have to go full on populist and say the quality of his work should be judged by its effects on high school dropouts, but I do think any reasonable definition of quality has to speak to an audience that is broader than specialists in a field.

Someone brought up to me the question of architecture and asked whether I wouldn’t agree that modern buildings are less beautiful than some of those created in the past. Chris Rufo points to presidents, arguing that Washington and Lincoln are better than more recent leaders. I don’t think that these are useful analogies. Creating a building depends on having a lot of capital and what government regulations will allow you to do. A president’s “greatness” seems to depend mainly on whether he is involved in a major war, otherwise there’s no opportunity to make the most consequential decisions. Yet anyone with a brain and a pen and paper, or word processor, has the opportunity to write poems and plays. Literature is more like running than architecture, and here we see that records keep getting broken.

It’s a curious pattern that whenever we have objective measures of something, the best performers are always from the recent past. This holds for running, darts, field goal kicking, weightlifting, memorizing the digits of pi, and chess. It’s only in subjective fields that require aesthetic appreciation that we see the supposedly “best” performers being from long ago, in areas like theology, philosophy, and literature. The simplest explanation for these regularities is that humanity is getting better at everything all the time, due to increased population, more leisure time, greater wealth, the Flynn Effect, superior training, and more access to previous work and knowledge. But in areas where quality is subjective, people delude themselves by having a kind of affirmative action for the past. Exceptions to this rule that nothing was better in previous centuries might exist in some fields like architecture where an artistic production depends on the complex interplay of political, historical, technological, and economic factors.

It’s absolutely fine to have cultural landmarks, and also to appreciate an artist for his place in the history of literature. As I wrote in my case against books, it can be satisfying to read a poem or story knowing that you are part of a long tradition that extends into the distant past, and creating a common culture can be useful.

So I’m not against reading Shakespeare, or encouraging others to do so. Nor am I saying that he should be taken out of the libraries and replaced with Hanania Hamlet. People have to read something and I’m skeptical anyway that there actually are works that can be considered the “best” literature, that they would remain consistent over time as people’s tastes change, and that if such a thing did exist we could identify it. There’s furthermore nothing wrong with saying Shakespeare was great in the way Babe Ruth was, meaning the best of his time.

Why even argue the point on intrinsic greatness then? I think this is a proxy battle in some deeper debates, which explains the reaction on Twitter to SBF and my own reaction to that reaction. Rather than the Shakespeare question dividing people along the lines of conservative versus liberal, here you have rationalists and postmodernists on one side and more mainstream thinkers on the other. In other words, not right versus left, but conformity versus nonconformity is the relevant axis. Yes, I know that postmodernists are conformists in other ways, but they’re right in questioning the worshipful attitude conservatives have towards the Western canon. Pretending that art, literature, philosophy and other subjective fields were better in the past reinforces small-c conservatism. Demystifying Shakespeare should be part of a larger project to emphasize how much worse the past was on nearly every dimension. I think we can understand that while giving previous generations the respect they are due by appreciating the scientific and artistic achievements that have brought us to this point.

No, you could not create a fake Shakespeare by just taking any average writer and teaching him or her to ape Shakespeare’s style.

Shakespeare’s work isn’t enduring for its style--if anything the style only makes it harder to propagate his work into the future. Shakespeare’s work is enduring for his ability to portray themes through plot and character that capture what it is to be human.

You aren’t going to recreate that by teaching someone to write in impenetrable prose.

It's ridiculous to say Jesus was a good religion founder. We can see by statistics that there are bound to be much better prophets around today.