Successes of the American Empire I: A Free South Korea

Kim Jong Un is bad, and it's good the US is in his way

It is easy to criticize American foreign policy. Just wait until the US takes some action abroad, like invading Iraq, that seems to have terrible consequences, and point to what happened. Non-interventionists can gather an endless number of instructive examples, and when you put them together in a list one ends up with a compelling indictment of whatever it is people in Washington think they’re doing.

The problem with this approach is that while US failures are obvious and well known to anyone who follows the news, the successes are less visible. It’s not too difficult to figure out why. The media tends not to report on wars that didn’t happen, or foreign countries that see things gradually get better. Moreover, causation is difficult to prove. If one country didn’t invade another today, who is to say that there was a realistic possibility of this happening in the first place?

It’s therefore worthwhile to take a step back and do the extra work required to uncover what are arguably some successes of a militarized US foreign policy. These are situations where the American use of force or the threat thereof in the form of for example, military bases, plausibly led to a better outcome than what we would have seen in its absence. Again, counterfactuals are difficult here, but I believe that there are many examples where US military power was exercised in a way that was at least plausibly beneficial for humanity. You likely already know about American failures abroad. To be able to have a fair and balanced opinion of US foreign policy requires one to also be familiar with its arguable successes.

This is the first in a series of posts highlighting such cases. We can start with one of the easiest examples of a beneficial policy one can find, which is the US commitment to defending South Korea.

The Advantages of Running a Slave State

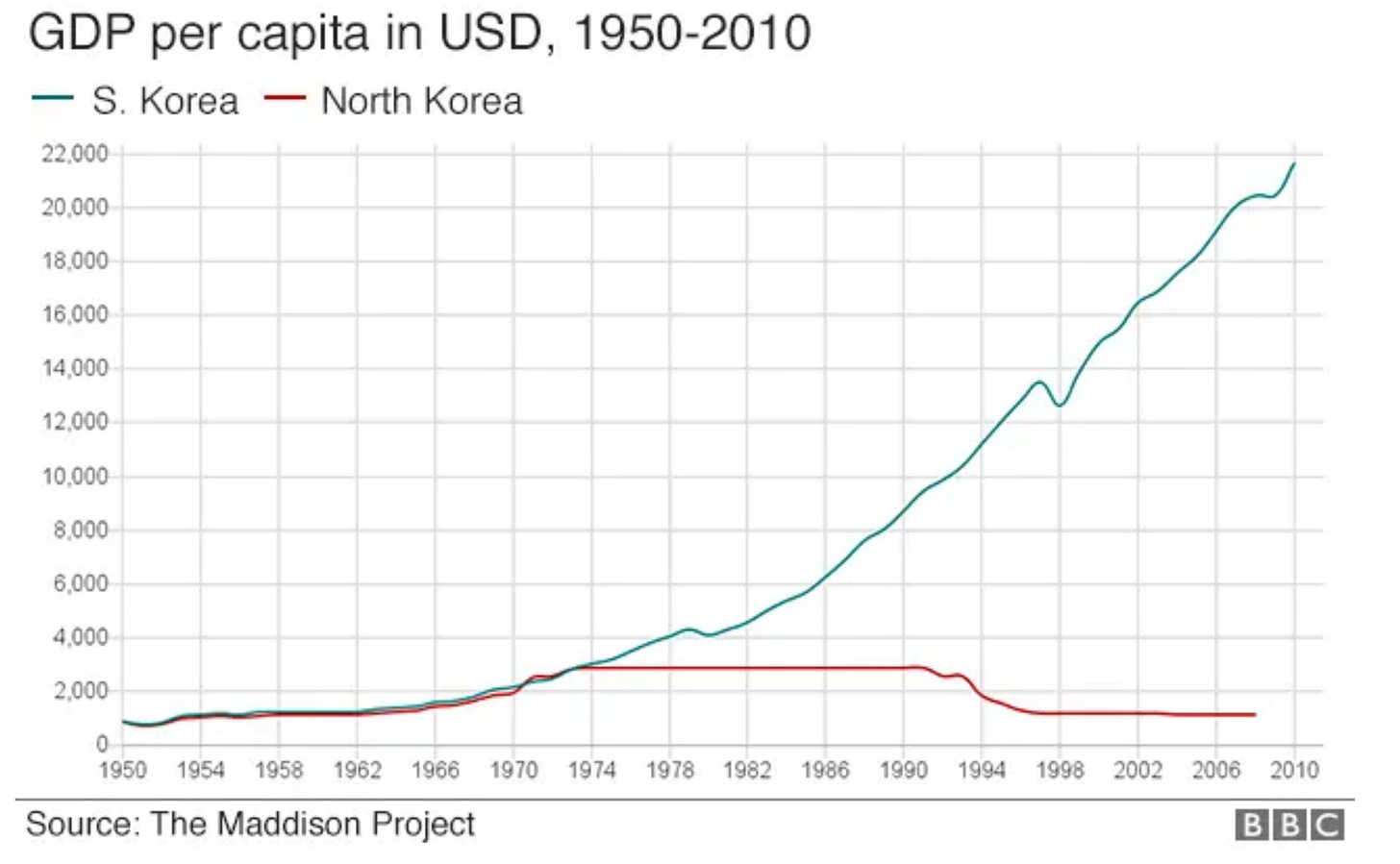

Until the 1970s, North Korea and South Korea were about equal in wealth and living standards. And then this happened.

Today, South Korea resembles Taiwan, Singapore, and Japan, as a successful East Asian economy with a high standard of living and social peace. It has the worst birthrate in the world, but I don’t think that this has a geopolitical explanation, or that most people would trade its current living standards for more babies. One could try to argue that US foreign policy emasculated South Koreans or something and made them stop forming families, but this would be a just-so story. The higher birthrate under Kim actually poses an interesting philosophical dilemma, though I just conducted a poll on X that indicates most people think it’s not worth it.

GDP of course doesn’t tell the whole story. North Korea is not only one of the poorest countries in the world, but by any reasonable measure the most repressive. People are executed for consuming and distributing foreign media, no one is allowed to leave, and the regime maintains large multigenerational slave camps.

The division of Korea into two countries was a historical accident. In the final days of World War II, the Soviet Union invaded Japanese territory in mainland Asia, including Korea. The US was in the process of taking Japan itself, and the two superpowers agreed to divide the country at the 38th parallel, an arbitrary line that split the nation in half.

To make a long story short, in 1950 Kim Il Sung tried to unite the peninsula, and almost succeeded before being driven back by American-led forces. When a ceasefire was declared in 1953, the armistice line was exactly where it had been at the start of the war. The 38th parallel has remained the de facto border between the two countries ever since.

Today, South Korea hosts 28,500 American troops, there to prevent a new invasion from the North.

Given that South Korea is the much larger and wealthier country, one might think it should be able to defend itself pretty easily. Yet there are certain advantages to running a slave state. According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies, North Korea has 7,769,000 active or reserve military personnel, which is the highest number in the world. It’s not as if South Korea skimps on defense, as it is in second place, with about 6.7 million. North Korea is also one of only 9 countries in the world with nuclear weapons, and is thought to maintain a significant quantity of chemical and biological weapons. Moreover, North Korea’s birth rate is probably about double that of South Korea, which means the population gap between the two countries is shrinking, especially among the younger cohorts who will be doing most of the fighting in case of war.

If both nations made full use of all available resources, South Korea would certainly be the stronger party. But living a civilized existence means that, while it may have more money and better technology, it might not be able to mobilize all of society in the single-minded pursuit of a goal, nor match the indifference to casualties its more brutal neighbor would show in the case of conflict. It’s also important to note that winning a war that is fought with weapons of mass destruction is not much of a victory anyway. As things stand, the assurance that Washington will defend American troops in the case of war helps to preserve the peace in East Asia.

Kim’s Intentions Are Unknowable

One could credit the US for South Korea continuing to be a free and prosperous country. Kim Jong Un’s grandfather once sought to unify the Korean peninsula and that has been the stated policy goal of the regime ever since. Although there has been recent talk of declaring the South a “primary foe” that needs to be occupied and subjugated in case of war, instead of part of the same nation, that seems worse.

A skeptic of US foreign policy could make the opposite argument. Invading South Korea would be a crazy thing to do. Kim Jong Un is rational in fearing the American military on his border, and not necessarily wrong that we’d like to see him overthrown. So of course he’s going to maintain a giant military and hold on to his nuclear weapons. Instead of being a force for peace, the US is in fact exacerbating the conflict.

There are reasonable people on both sides of the issue, and evidence on the ultimate intentions of the North Korean regime is difficult to come by. Kim Jong Un himself may not know exactly what he would do if the US withdrew from the Korean peninsula. It would be a completely different world in which he would be exposed to new sources of information, hear new arguments from his advisers, face pressures from other powers, and perhaps need to devise a novel propaganda campaign to justify the continuation of his regime, all with unpredictable results.

North Koreans are taught from a young age that American devils are responsible for dividing their homeland. If the day comes when they aren’t there anymore, it begs the question of why forcible reunification can’t go forward. According to BR Myers’ The Cleanest Race, the North Korean government can no longer hide the fact that the South has much higher living standards, and openly admits this in internal propaganda. Racial and cultural purity has therefore become the entire justification for the existence of the regime. An American withdrawal would force North Korea to grapple with a brand new understanding of itself and its place in the world, and nobody can know where that would lead.

When it comes to the question of whether Kim Jong Un would be crazy enough to launch a war against South Korea, we should remember that leaders make dumb decisions all the time. Before late February 2022, one argument against the idea that Putin was going to march to Kiev was that he hadn’t amassed nearly enough troops to occupy Ukraine. The analysts who talked about this ended up being correct from a military perspective, but, as we saw in the Tucker interview, Putin is pretty delusional, and his regime relied on faulty intelligence indicating that Russia had sympathizers in positions of power throughout Ukrainian society who would be able to deliver the country. Recall also Dick Cheney’s infamous prediction that the US would be “greeted as liberators” in Iraq.

Kim Jong Un is likely to have a view of the world that is much more distorted than that of either Putin or Dick Cheney. He may well believe his own propaganda, and think that all Koreans everywhere are yearning to be reunited under his wise leadership. It’s a problem when we assume that foreign dictators are like us, not understanding that the position they are in can often cause them to be detached from reality, since those around authoritarian rulers have a tendency to provide them with selective information and tell them what they want to hear.

In the end, people should think in terms of probabilities rather than pretend that they know what would happen if the US pulled out of Korea. If there’s even a 10-15% chance Kim Jong Un would try to conquer the South, it’s probably a good idea to keep the American military there as a deterrent force. No matter what else the leader of North Korea might believe about the world, American power is too obvious and overwhelming for him to ignore.

One may therefore consider US foreign policy towards Korea from 1950 to the present to have been a massive success. Kim Il Sung would have conquered the South without American involvement, and since the Korean War ended we’ve had 71 years of the same family in power without it undertaking another invasion. Over that time frame, North Korea has shown practically no progress in terms of economic development or human rights, in many ways becoming worse, but has successfully built nuclear weapons, as South Korea has turned into a safe and prosperous democracy.

I’ve sort of conflated two questions here, which are whether the US has historically been a force for good on the Korean peninsula, and whether it is a force for good today. In theory, each of these questions might have a different answer, but in practical terms virtually everyone either answers yes to both or no to both. This is because we are dealing with a world of uncertainty, and analysts generally must rely on their own usually highly disputed assumptions in forming opinions.

No one knows what would have happened if the US had withdrawn from Korea in say 1985. Perhaps Kim Il Sung had mellowed in his old age, and there would have been negotiations that led to reunification, or at least peace and prosperity for both nations. Alternatively, the regime might’ve continued on the path it was on and surprised the world one morning by nuking Seoul. Of course, the South Koreans would not have stood still under those circumstances and may have tried to get nukes of their own. All of this could’ve ended in a strike by whichever side got to the bomb first, or a Cold War-like scenario of Mutually Assured Destruction that continued and made permanent the frozen peace we see today.

Yet, considering that the North Koreans have always said they want reunification while never again invading their neighbor, and the fact that we know that the regime doesn’t care about the human rights or the wellbeing of even its own people, much less foreigners, it seems to me that it is more likely than not that since 1953 the US has prevented at least one new Korean War. For not much money — the price tends to be exaggerated by America First types — and a relatively small risk of involvement in a major conflict, it helps maintain the peace in East Asia and avoid a war that could potentially draw in other powers. Things might be fine without the US, but pulling back now would be crazy given what could realistically happen. It’s completely possible that China and Japan would step in like grownups and prevent things from spiraling out of control, but it’s just as easy to imagine that the North Korean regime is actually serious about reunification and can only be stopped by a guarantee of American involvement in the case of war.

We Should Still Talk to Evil Regimes

Just because the US is overall a force for good in the world does not mean that Washington doesn’t make terrible mistakes. Here, it’s important to note that we have an insane policy of not having any lines of communication with hostile regimes. The US did not once talk directly to Saddam Hussein between the end of the Gulf War and the time he was overthrown. In 1998, Bill Clinton told Tony Blair that he wished he could just call the guy and figure things out but the press would kill him if he did. One of the reasons that Trump freaked out the foreign policy establishment was that he thought talking to foreign leaders wasn’t that big of a deal, and his willingness to meet with Kim Jong Un caused an uproar in official Washington.

As I wrote in Public Choice Theory and the Illusion of Grand Strategy, in the chapter on sanctions, this makes little sense from a policy perspective but is understandable when considering the incentives that American leaders face, as

policymakers show little interest in actually using the leverage that sanctions give them to achieve foreign policy goals. If the instrumental explanation of sanctions is correct, then the United States should, at the very least, talk to targeted regimes in order to make its demands clear and provide a clear path toward the removal of restrictions on trade. Yet American administrations have done the opposite, in certain cases both demanding the impossible from their adversaries and cutting off all contact. As Tariq Aziz, former Foreign Minister of Iraq, told his American captors, “We didn’t have any opportunity to talk to a US official during the Bush, Clinton, or new Bush administration, so there was no opportunity to talk face-to-face and address matters of concern. They always rejected us” (Woods et al. 2006:89). The United States today sanctions Cuba, Iran, North Korea, Syria, and Venezuela in order to remove their governments or significantly change their behavior, despite no clear path to regime change and little in the way of the most rudimentary channels of communication that would be necessary in order to facilitate a bargain. Politicians often attack opponents for even wanting to negotiate with certain regimes, as former senator John McCain did during the 2008 election when he called then Senator Obama “reckless” for being in favor of talking to adversaries (Bohan 2008). Interestingly, after President Obama assumed office he mostly stuck to the policy of not speaking to adversaries, indicating that political pressures coming from within the bureaucracy and the media lead presidents away from diplomacy. When the Obama administration did begin to openly engage in bilateral negotiations with Iran, it was only after years of engaging in secret back channels that were hidden from the public (Ignatius 2016).

Kim Jong Un’s ultimate intentions are the great unknown in terms of Korea policy, and the best way to find out more about what he thinks is to talk to him and his top officials. This doesn’t mean that you naively accept everything they say at face value. Even if you know someone is lying, you can still gain insight into what they believe and how they think through communicating with and being around them. In a world where so much depends on knowing the intentions of foreign leaders, we’ve consciously handicapped ourselves through refusing to engage. My ideal policy towards North Korea would involve leaving the American commitment as is while engaging in more diplomacy. If discussions don’t go anywhere, one doesn’t have to change the current approach.

The concern over Trump engaging in discussions with Kim Jong Un may have stemmed in part from a perception that the president didn’t really believe in the US alliance system. Therefore, there was a fear that, charmed by Kim's demeanor, he could have potentially conceded too much. A different president, one more predictable and who was seen as more committed to maintaining American power abroad, might be able to have different results. But the politics of this are very difficult. Washington loves virtue signalling more than solving problems. The House of Representatives by an overwhelming majority just passed a bill prohibiting normalization of relations with Syria, even though the entire region is working towards the reintegration of the Assad regime. The question isn’t whether the Syrian government is good, but rather what is to be gained from refusing to even talk to its leaders and representatives.

All that being said, recognizing that American foreign policy is often very stupid is not inconsistent with believing that over the last three quarters of a century the assertive use of US power has usually made the world a better place.

If I can make a suggestion, I think you should also also write an article about how many wars capitalist countries had against each other afther WWII and how many wars socialist countries had against each other in the same timeframe. Just to debunk the marxist mythology about "MUH...capitalism cause wars!!!111"

Saying that South Korea's wealth and freedom is a "success" of the American Empire seems like a bit of a stretch. There is perhaps some truth to it, but not as much as you suggest. I say that because for decades after the Korean War the South was neither democratic nor wealthy in the way it is today. Syngman Rhee's leadership was brutal, repressive, and resulted in the poverty of millions. South Korea did not elect a leader until 1987, 34 years after the war. While today things are obviously different it is not at all clear what role the American Empire played in that success (at least from your article) considering how South Korea was closely allied with the US throughout the Cold War yet remained oppressed and impoverished throughout much of that time.

Most of the article is a valid criticism of the North. But who needs reminding that North Korea is run by a reprehensible and despotic regime?