The last time I saw Bryan Caplan, he told me that Tyler occasionally trolls him by saying that for all his pretensions towards being some kind of unique maverick, he’s at heart just a very normal guy. This made me laugh, as I thought no one has ever trolled me in that way before. Whether I’m close to people or more distant, spend short or large amounts of time with them, they all seem to know that I am very “different.”

It wasn’t until a few years ago that I first ran across the symptoms for Asperger’s. Here’s one list, as applied to children.

Difficulty with social interactions and social language

Not understanding emotions well or having less facial expression than others

Not using or understanding nonverbal communication, such as gestures, body language, and facial expression

Conversations that revolve around themselves or a certain topic

Speech that sounds unusual, such as flat, high-pitched, quiet, loud, or choppy

An intense obsession with one or two specific, narrow subjects

Unique mannerisms, repetitive behaviors, or repeated routines

Becoming upset at slight changes in routines

Memorizing preferred information and facts easily

Clumsy, uncoordinated movements, including difficulty with handwriting

Difficulty managing emotions, sometimes leading to verbal or behavioral outbursts, self-injurious behaviors, or tantrums

Not understanding other peoples’ feelings or perspectives

Hypersensitivity to lights, sounds, and textures

Many of the traits on the list describe me perfectly as an adult and, as I’ll discuss below, practically all of the rest I used to have but eventually grew out of. The thing about this group of symptoms is that they seem largely unrelated to one another. What does bad handwriting have to do with liking routines or not understanding social interactions? Yet somehow, psychiatry had put together a list that tied it all together and that I could see applied to me.

When I read the Asperger’s symptoms to my wife shortly after discovering the list, we cracked up after every one, instantly recognizing each trait. I’m weird, but medical science had an explanation! My inclination is to think that psychiatric diagnoses are fake, but I can’t deny my lived experience. The Asperger’s symptoms read as if they were written by somebody who followed me around as a child and decided to just make a list of the quirks they observed. Whether it’s good to actually diagnose these things is a different matter; I think being labeled with a disorder at a certain age could’ve easily turned into a self-fulfilling prophecy and made overcoming some of the downsides of Asperger’s more challenging, and it’s probably not an accident that greater “mental health awareness” among younger generations has coincided with worsening mental health.

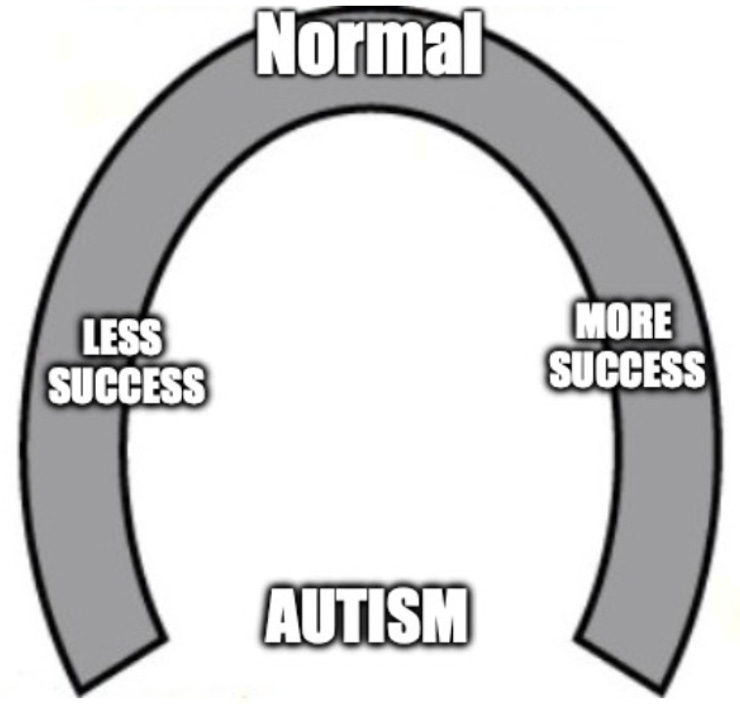

Regardless, I think that there are broader lessons from my story, which makes me believe that there’s a kind of Autism horseshoe. The idea is that both the most and least successful people you know are more likely to be somewhat autistic.

That’s because they share at least two things in common.

Passion for something in life: That is, words, expressions, and an overall attitude that communicate that something in this world matters beyond superficial goals like status climbing and sensory gratification. This can be leading a political movement or pushing the frontiers of technological progress, or alternatively retreating into a fantasy universe and weird obsessions that bring no tangible benefits to the world or even the hobbyist himself.

Emotional distance from others: The ability to maintain one’s sense of reality under varied circumstances. Being less likely to change one’s tone, gestures or behaviors depending on what else is going on in the environment.

These are traits that are sometimes associated with mass shooters, suicide bombers, and criminals. You may also see them in those with an unusual ability to influence or inspire others, namely cult leaders and highly successful CEOs, as can be seen by Elon Musk self-diagnosing himself as “on the spectrum.”

For those with Aspie traits, this is potentially good news. I don’t want to exaggerate this or imply that going from the bad kind of autism to the good kind is easy or something that can be done overnight. But I think my own story demonstrates that it is possible, given that I’ve been able to turn some of what used to be my biggest weaknesses into strengths.

Misunderstanding Social Cues

Musk has described what it was like growing up with Asperger’s. In part, he says,

I would just tend to take things very literally… but then that turned out to be wrong — [people were not] simply saying exactly what they mean, there’s all sorts of other things that are meant, and [it] took me a while to figure that out.

People might be shocked at just how literal the human mind can be. When I was in grade school, I knew a kid who would sometimes sarcastically say “yeah right.” For a while I was very surprised by this and wondered what was going on. Why did he always say “yeah right” in response to something that he clearly believed was wrong or even ridiculous? I eventually realized that this is what humans call “sarcasm.” It was very disorienting at the time, as I had no clue why anyone would do this. It felt like learning that sometimes people say “up” when they mean “down” for no good reason. I think I understand this concept now and can employ it very well, and I obviously no longer have to remind myself someone is “doing sarcasm” on a daily basis. But things that are second nature to most people would often for me take a lot of time and effort to sink in.

For much of my adolescence, I was deeply depressed, and this was closely related to not being able to understand other people or form relationships with them. To give one example of how this works, let’s say you’re trying to hang out with someone and they respond, “I can’t this week, my uncle’s in town.” You try again, and then they say, “I’ll let you know, my grandma is coming over.” A normal person understands the subtext, which is that the guy who you think of as your friend doesn’t really want to spend time with you. But if you don’t realize people do this, you just think to yourself “gee, this person really likes to spend a lot of time with his family.” And you may ask a third time, at which point they’ll say that they have a doctor’s appointment and you might finally start to get suspicious, but people then like you even less than they did before because now they see you won’t take an obvious hint. Many are sadistic, and will even take pleasure in lying to someone who is naive in this way, stringing them along, or getting their hopes up with regards to potential social opportunities.

This hypothetical focuses on words, but most socially normal people don’t even need things to get to that point, where someone has to make up an actual lie about seeing their grandma. Usually, just from things like body language or voice intonation, most individuals can tell who is seeking out a relationship and who is closed off. I really came into the world expecting a social landscape where people went around like robots telling others exactly where they stood in relation to one another, and when I saw that normal people didn’t do this I developed a kind of superiority-inferiority complex towards them. They were spineless and dishonest, but at the same time possessed skills I couldn’t help but be in awe of, namely the ability to understand, relate to, and manipulate others.

I once saw a naive concern with truth listed as a symptom of Asperger’s, and I brought that trait with me when I started engaging with ideas. My first memorable encounter with blank slatism was when I took a cultural anthropology class at the University of Colorado. The professor confidently asserted that male/female differences were socially constructed and “proved” this through studies showing that boys and girls are treated differently as kids. I would seek him out after class and send him emails about how this was all nonsense. One thing to understand is that I had grown up without knowing a lot of people who had gone to college, alienated from the dumber but somehow socially more skilled kids around me, and I had this romantic idea of a professor as being a smart person who had dedicated his life to truth. This professor, however, couldn’t refute any of my arguments and at some point just said something along the lines of that for the sake of this class, we’re going to assume that all differences we observe between groups are based on how society treats people. They were of course all like that.

Learning this was really shocking to me, and I came to have contempt for the entire academic enterprise. I was naive enough to think that if I sent him papers grounded in sound methodology or framed the argument in the right way, he would one day stand up in class and say that I had shaken his worldview, all of his life was a fraud up to this point, and he now realized that biology is actually a thing. While before going to college I already knew that proles didn’t have intellectual interests or care about what’s true, I thought that more educated people, and especially those who engaged with ideas, were different. But they were just as irrational, and in a certain sense more offensive to my sensibilities because they gave the pretense of being open minded and engaging in honest scholarly inquiry.

So for many years I would argue with people and try to get them to believe whatever I thought was correct, and in some cases it actually worked even on the most controversial issues, but usually it was a waste of time and bad for my social and career prospects. Thankfully, now I make a living by offering unpopular opinions, which I guess is a very clear example of taking a maladaptive trait and putting it to good use.

Growing up, there was a vicious cycle in which bad social skills led to depression, which caused me to be something of a shut-in and avoid other people, and brought down the mood of everyone around me. Here I’m focusing on the autism part of my past, but the depression probably deserves its own post at some point. What broke me out of this was discovering writings and lectures focused on self-improvement, particularly those with an emphasis on how one could be more attractive to women, which was usually my main concern when I was younger. But getting good with women ends up helping you in every other area of social life. It’s rare that you meet a man who is skilled at winning over other men but is a complete failure with the opposite sex, or vice versa. Males and females are of course very different, and it’s important to understand how, but the vast majority of social skills are transferrable across contexts.

Learning Social Skills from First Principles

So far my childhood and adolescence sound very sad and pathetic, and they were. But in the long run there was an advantage in having to learn social skills from the ground up. Most people have an intuitive understanding of ideas like “sarcasm” or “letting someone off gently when two individuals have different understandings of the current status of their relationship.” These were completely foreign concepts to me, but having to learn about them from things like books on evolutionary psychology and observing how people interact with one another eventually gave me a deeper understanding of the complex dynamics at play in everyday social interactions that most people take for granted.

Sometimes, when a person wants to comment on some quirk about our society or culture, they ask others to imagine what an alien species investigating us would say if they saw what we were doing. The idea here is that we as human beings who have accepted the norms of our place and time cannot provide an objective assessment of social practices, but a completely different species, or historians in future generations, might be able to. As with our scholarly aliens, the autist has a unique perspective that results from being detached from the rest of humanity, and when that is combined with raw intelligence and the willingness to learn, he can achieve unusually high levels of insight and understanding.

Many of my most read articles involve some analysis of social relations, like “Anti-Woke as Autism.” Fans I meet most often seem to want to talk about my article on women’s tears. It apparently provides a unique perspective on the free speech issue that resonates with people’s understanding of sex differences and how men and women interact with one another, while coming from an angle most readers hadn’t considered before. That I would one day be able to write articles analyzing social dynamics that many readers find compelling would’ve been very surprising to anyone who knew me when I was younger. But maybe I was always more likely to eventually produce such work than a normal person with similar intelligence, since they would never have been forced to reflect deeply on things like how people are often motivated by subconscious impulses unrelated to what they say, and the subtexts of different kinds of social interactions.

Men were hard enough to figure out, but women represented a higher-level challenge. Autism has been described as a kind of extreme male brain, and women specialize in things that many people on the spectrum struggle with like understanding subtle social cues and nonverbal communication. This naturally can lead to misogyny. One way to understand sex differences is to frame women as the more dishonest half of our species. Plus, they’re needlessly cruel, always telling you that you’re a “nice guy” that other women would be lucky to have, even though they never let you sleep with them or even lick their boobs. Bitches. Of course giving such devious creatures the right to vote was the beginning of the end for Western civilization! A more balanced view of intersex relations brings understanding that one reason evolution made women good at social dynamics is because men do things like rape them and sell them as property, and even in liberal societies males they come into contact with spend much of their time thinking about their bodies and what it would be fun to do to them. And an even deeper understanding leads to the realization that getting mad at one sex or the other for being a certain way is stupid, since we’re all just products of chemical interactions, and most of the time when individuals are comparing the virtues of men and women from either end of the political spectrum they are just motivated by a desire to feel better about their own personal inadequacies.

Once the autist actually learns how to interact with other people and internalizes the necessary lessons, he may find that he can now beat the normies at their own game. Being obsessed with certain topics, caring about truth and perceiving it more accurately than others, and indifference to the opinions of people who would doubt what you’re doing are signs of being on the spectrum and also in some ways important traits to have as an entrepreneur or influential cultural figure. But these potential psychological assets will go to waste if you don’t have confidence and learn the mechanics of how to interact with your fellow humans, and whether all of this eventually clicks for someone on the spectrum can determine how their life turns out.

Leaning into Strengths

What characteristics decide whether someone far along on the autism spectrum becomes a success or failure? In my case, the path to a more functional existence involved deliberately learning some science, which meant diving into literatures related to evolutionary psychology, personality psychology, and behavioral genetics. Again, this was not easy. I worked harder at improving my social skills than I have at any other thing in my life, and I am a very hard worker! But luckily I had the genes for the ability to maintain obsessive focus towards the things I care about. Autism was turned against itself.

If going from bad to good autism involves reading and understanding academic literatures, then a high IQ is necessary. But I don’t think that most people have to go anywhere near that far. The Cliffs Notes versions of the most important insights that trickle their way down to the pick-up artist community, if it still exists, and other folk or more organized self-help systems don’t require that one be a genius to understand them. Nonetheless, IQ is basically a measure of the ability to learn, and even if you’re not going to spend any time reviewing academic papers, a more intelligent individual will naturally be better equipped to consciously seek out and accurately interpret various sources of information, including personal experience. The psychologist Linda Gottfredson has talked about the usefulness of general intelligence for dealing with novel problems, which is why it correlates with practically every important outcome we can measure.

One trait that some Asperger’s types have that I can’t relate to is a tendency to become obsessed with minutia and irrelevant nonsense like train schedules. I get the idea of having intellectual obsessions, which consume much of my life. But since I was a teenager, I have always been interested in big picture questions related to things like politics, international relations, and the overall trajectory of humanity. One can make a living and inspire others if you have a personality that is atypical but are nonetheless passionate about topics that are of deep interest to others. If you have the type of Asperger’s that makes you feel compelled to stack cans and do little else, that might be a problem, though even here, an ability to become absorbed by things others find boring is a good trait to have if you’re going to be an engineer or computer programmer.

If you’re as psychologically unusual as I am, trying to move towards “normal” is probably not the best option. It’s likely hopeless anyway, and will lead to frustration. The point in my life I made the greatest effort in that direction was during law school, when the major firms came to interview us on the University of Chicago campus. To prepare, you were supposed to do stuff like remember the names of the firms and explain to them why you wanted to work there. I found it so demoralizing to try and chase after a normal corporate job that I dropped out before the process was finished, which no one ever does, knowing that I’d have to do something else with my life.1 I thought academia would be more bearable for someone who was independent minded, but that obviously seems laughable in retrospect. If I hadn’t gone off on my own, I think I could’ve toned down the offensiveness and worked in politics or the think tank world, but whatever the case might be I had to end up doing something that I felt mattered and was connected to the ideas that I was naturally interested in.

I think if you’re reading this, there’s a better than average chance you’re at least a little bit autistic. Diagnosing one’s self as on the spectrum has become trendy among types who talk politics on Twitter, and I sometimes get offended at this, seeing it as a kind of cultural appropriation. But I don’t think it’s just about people trying to be cool. Part of being on the spectrum involves caring a lot about something, and it’s easy to underestimate how many people are completely devoid of any passion. From my experience, these types seem to go to law school in pretty high numbers (no offense to those of you who ended up as corporate attorneys!). To have anything resembling a political ideology that fits together already makes you somewhat unusual.

I don’t have anything against anyone who works a normal job. The capitalist system and our modern standard of living depend on the existence of large numbers of people who just want to figure out the best way to make money and therefore respond to what the market is telling them when deciding what they should be doing with their lives. In my case, however, functioning without some kind of higher purpose on a daily basis is impossible. I’ve found that whenever you meet a happy person who is working a job that involves what from the outside seems like pointless drudgery, they practically always have a strong religious faith, which is just another way to achieve meaning in life, and probably the most realistic path towards finding it for much of humanity.

If what I write here about being on the spectrum resonates with you, I would suggest leaning into what makes you different, rather than running away from it. Normalcy sucks anyway, and caring about things is what gives life meaning. Most people are just treading water, and in my experience few seem genuinely happy or fulfilled most of the time. While social skills can to a large extent be learned, I’m not so sure the same can be said for what we might call the romanticization of everyday life, which for me begins with simply caring about truth and believing that it matters.

My friend Chris Nicholson, who was attending Yale at the same time, told me he had a similar experience during on-campus interviews, minus the dropping out, and he also went on to get a PhD, philosophy in his case, after law school. In another parallel, Chris didn’t end up pursuing a career in academia, and now even does podcasts with me on TV shows and the Ukraine War. We probably get along because we share a lot of traits in common, though he’s like the more subdued Asian version, and as far as I know had a happy or at least more normal childhood.

Re gaining greater insight by learning something that doesn't come naturally to you, I recall reading an interview with an elite swimmer, who at the time was considered to have the best butterfly stroke in the world. She said she could never coach anyone, because it came so naturally to her she had no idea what she was doing that others weren't. Conversely, my impression is that good football coaches are more likely to have been mediocre players than great ones. (Though that could be just because there are more mediocre players.)

I had a similar experience growing up. I never fit in. Social skills and relatability were just mystifying to me, and I had absolutely no interest in the typical "teenage girl" pursuits, much preferring to ride my horse or play with Legos. As a pre-teen I was obsessed with dinosaurs and would constantly correct my teachers on their pronunciation of dinosaur names or whatever. I was one of those annoying straight A students that never had to work very hard to learn anything and outperformed virtually everyone on any metric. Unlike the male Aspies however I was very athletic and excelled in sports as well as academics. I had very few friends and was bullied quite a bit.

Fortunately or unfortunately for me I've always been horse-obsessed, and that has driven much of my life, first as a professional rider with success in competitions on a national level, then as a trainer and teacher. Teaching forced me to improve my social skills, and in true Aspie fashion I've spent a ton of time researching different teaching methods and watching elite coaches give lessons, in addition to studying the sports psychology, behavioral theory, among other relevant topics.