When justifying economic populism, politicians and thinkers from both the left and right constantly complain about trade with China and what it did to the American heartland. Trump of course is the political figure most associated with anti-trade views, but in 2000 Bernie Sanders came out against establishing permanent trade relations with China, which he saw as “a vehicle for companies to send jobs to a country that allows its workers to be paid 20 cents an hour.”

I remember when I beat Grand Theft Auto V, one of the endings has the three main characters murdering an obnoxious tech bro, and one of the reasons they tell him he deserves to die before slamming the trunk and pushing the car off the cliff is that he offshores jobs to save money. This showed me that economic populism of a nationalist bent has deep cultural roots.

Such views have gotten a boost in the last few years from what is called the “China Shock” literature, which has been seized on by protectionists to argue for their preferred policies. There has been a bipartisan turn towards hawkishness on China, with Biden having kept many of the trade restrictions put on by the first Trump administration, and adding more on top of them. The second Trump administration has of course taken the trade war to a new level.

Unfortunately, protectionists misrepresent or misunderstand the China shock literature, which doesn’t argue that Americans were made worse off. Even setting that aside, the main scholars who have written such papers do not call for protectionism going forward and still support free trade. More fundamentally, those who are against trade with China make a more basic error about the way the economy works. Creative destruction is necessary for economic and technological progress. When you don’t see some areas of the country get left behind, that itself is an indication that something is going wrong.

Many Americans have an instinctual revulsion towards China – some of it justified, some of it just racist and dumb. So these debates have a kind of whack-a-mole quality. If you say trade with China is mutually beneficial for both countries, people will respond that you don’t care about Hong Kong or the Uighurs. They’ll sometimes argue that we were told that China would democratize but it didn’t, which means those who favored the expansion of trade were wrong. This is odd, because no one has ever explained how protectionism is supposed to stop China from violating human rights. Since we don’t have the ability to influence whether China becomes democratic either way, we might as well just engage in mutually beneficial trade.

Another thing China hawks will do is bring up national security considerations. In case we’re at war with China, the reasoning goes, we want to be able to make our own stuff. That potentially makes sense, but this would only justify narrow restrictions on some kinds of technology, and perhaps support for American industry in areas critical to national security. What the Trump administration is doing is almost the complete opposite of that. They put huge tariffs on children’s toys, while rolling back Biden-era restrictions on semiconductors. The Biden administration itself complained about China “flooding global markets with artificially low-priced exports” – in other words, benefiting Americans by providing them with goods and services for less than they would otherwise pay. I’m willing to listen to suggestions about measures we need to take as insurance in case we end up at war with China. But in practical terms, the national security justification is commonly invoked to argue for policies based in demagoguery and economic illiteracy. Often, leaders will claim that some industry is critical for national security, but they don’t take the price system seriously enough, as the need to innovate creates incentives to find substitutes for goods and natural resources when access to them is threatened.

Creative Destruction

Politicians – and populist intellectuals appealing to less informed citizens – will often talk about creating or protecting jobs as a goal of public policy. This misses the entire point about how innovation works. People living during earlier points of human history worked just as hard if not harder than people work today. The reason we enjoy living standards so much higher than them is that we have access to more science and technology, including knowledge in areas like logistics and industrial management. Practically every product that you use put someone at some point out of a job. The automobile destroys the need for the horse carriage driver, in addition to blacksmiths who made horseshoes, stable hands, carriage makers, and feed suppliers. Mechanized plows and tractors replaced teams of men who once worked acres by hand or with oxen. In 1800, about 75% of the labor force worked in agriculture; today, less than 2% feed the entire country and export food abroad. Paul Krugman points out that David Ricardo was worrying about us running out of jobs in 1821, showing that this fear has been with us for a very long time.

Having learned from history, modern economists generally don’t think like this. There’s a likely apocryphal story of Milton Friedman traveling in China and asking why a public works project had laborers digging with shovels instead of using machinery. When a government official replied that this was to create jobs in the construction industry, Friedman asked why they didn’t then have them use spoons instead. Economists love to tell this story for the way in which it demonstrates the fallacy of focusing on creating jobs as a public policy goal.

I remember once seeing a meme circulating arguing that renewables created more jobs than fossil fuels per unit of energy. This was supposed to be an argument in favor of clean energy, but it gets things exactly backwards. To see why, take the argument to its extreme and imagine that there is a form of energy production that would give us all the energy we have now but need to utilize the entire workforce. In that case, the economy would provide literally nothing else. Of course, set aside here the obvious fact that everyone would starve to death because all we would have is energy and no other industry. What would really happen if the energy industry were that inefficient is that we would just use a lot less energy and have a much worse standard of living. In contrast, imagine we could get the same amount of energy we have now with only one worker. Society would become a lot wealthier, because we’d have an equivalent level of energy, plus it would free up a lot of other labor in order to produce goods and services people want.

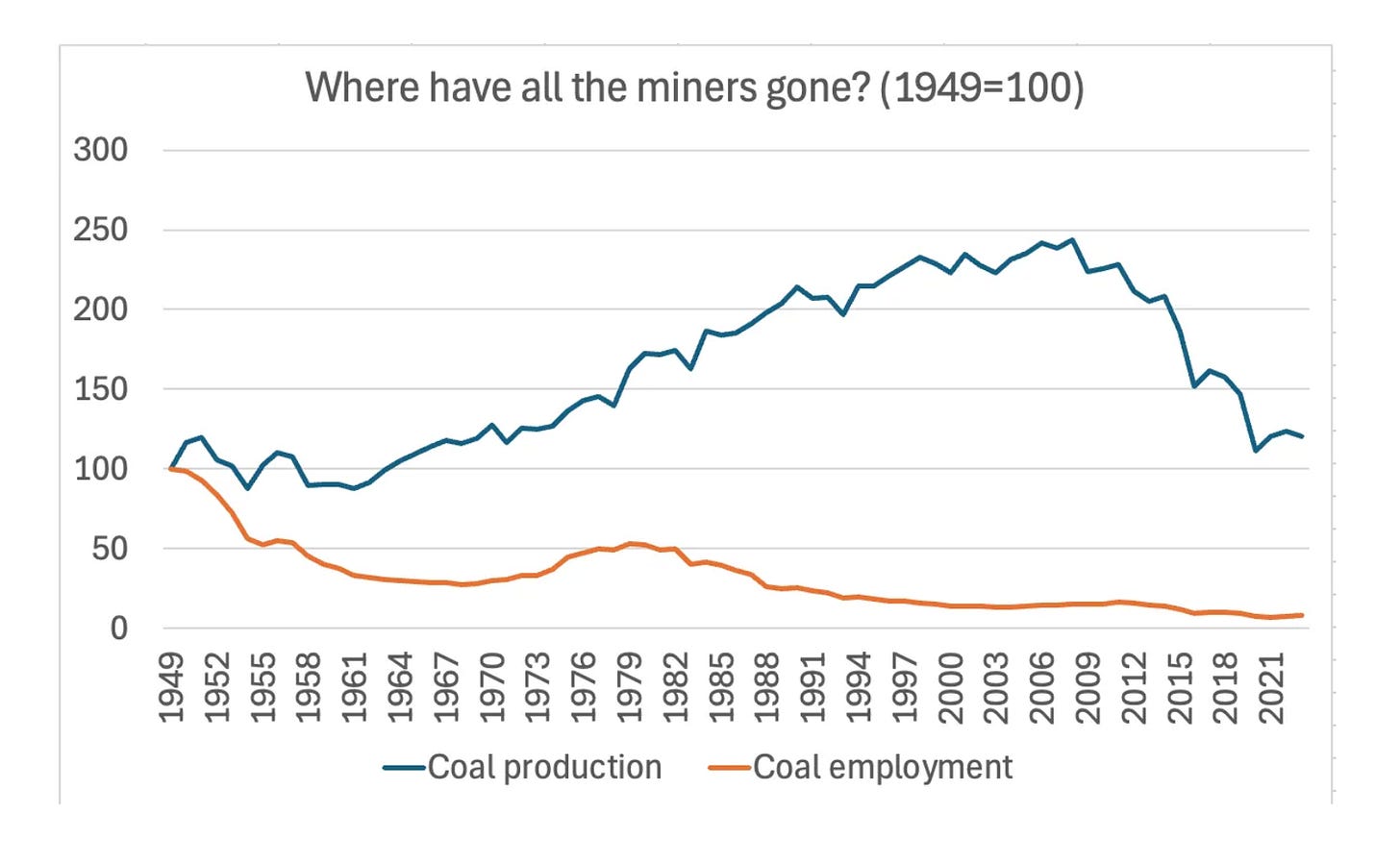

You can see this in what has happened in coal mining, where production has increased as the number of people working in the profession has declined.

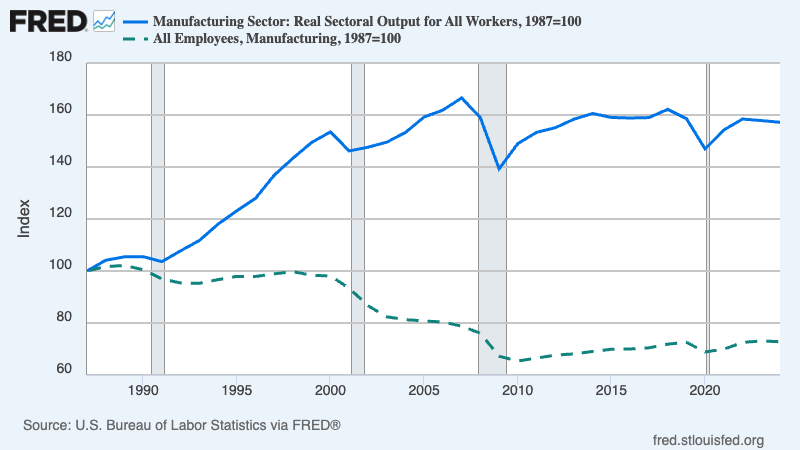

We can also observe something similar in manufacturing. Production has gone up 57% since 1987, with 27% fewer workers.

So when people say “we don’t make things in America anymore,” they’re wrong! We make as much as ever, we just do it by employing fewer people, which is kind of the entire aim of economic progress.

At this point, you’re probably wondering whether we can take this logic too far. Imagine AI that can do literally everything humans can, at which point there will be no need for people. Maybe we’ll get there eventually. We can say for now, however, that there is zero evidence we’re anywhere near that point. Here is the US unemployment rate for those 20 years and older from 1948 to the present.

There is no indication that we are running out of jobs, despite increasing international trade and technological developments. The AI singularity putting us all out of work is still a theoretical possibility, and if we’re worried about it we should just try to stop AI specifically, rather than trying to create or save jobs in particular industries on an ad hoc basis. I’ve previously written about why nobody should worry about this possibility in the first place, and there’s no reason to rehash the same arguments here.

Now, since jobs need to be destroyed if we’re going to have any progress at all, that means that certain regions and towns must decline, particularly in places where concentrated industry no longer meets the needs of the economy. This is a natural process. When people came to live in factory towns in Pennsylvania and Ohio in earlier generations, they left some other places behind. There were adjustment costs and it was perhaps bad for declining communities, but there was no better way for individuals to improve their standard of living. Today, people look back with rose-colored glasses at earlier generations and think that everyone should have stayed exactly where they were in 1980 or maybe 2000.

Today, YIMBYs and abundance types explain how cities like San Francisco and New York City should have much larger populations, but they are stopped from growing due to restrictions on housing, which drive up prices and keep out the poor and middle class. But, setting aside immigration, if certain regions of the country grow, it means other places must decline. If it makes sense for more Americans to live in San Francisco, which they would if not for burdensome housing regulations, fewer must live somewhere else. And since the weather sucks in Ohio and Wisconsin and there’s no particular reason for more people to live in such places, it would make sense if the left behind communities were concentrated in such states.

All of this is to say that, if trade with China destroys some jobs and causes certain American communities to decline, that means the policy has worked. In an interview that JD Vance did before the election, Ross Douthat asked about his economic populist vision. I thought that the response was quite funny.

The main thrust of the postwar American order of globalization has involved relying more and more on cheaper labor. The trade issue and the immigration issue are two sides of the same coin: The trade issue is cheaper labor overseas; the immigration issue is cheaper labor at home, which applies upward pressure on a whole host of services, from hospital services to housing and so forth.

The populist vision, at least as it exists in my head, is an inversion of that: applying as much upward pressure on wages and as much downward pressure on the services that the people use as possible. We’ve had far too little innovation over the last 40 years, and far too much labor substitution. This is why I think the economics profession is fundamentally wrong about both immigration and about tariffs. Yes, tariffs can apply upward pricing pressure on various things — though I think it’s massively overstated — but when you are forced to do more with your domestic labor force, you have all of these positive dynamic effects.

It’s a classic formulation: You raise the minimum wage to $20 an hour, and you will sometimes hear libertarians say this is a bad thing. “Well, isn’t McDonald’s just going to replace some of the workers with kiosks?” That’s a good thing, because then the workers who are still there are going to make higher wages; the kiosks will perform a useful function; and that’s the kind of rising tide that actually lifts all boats. What is not good is you replace the McDonald’s worker from Middletown, Ohio, who makes $17 an hour with an immigrant who makes $15 an hour. And that is, I think, the main thrust of elite liberalism, whether people acknowledge it or not.

So if a minimum wage worker is replaced by a machine, he can level up and become a manager or something. If he is replaced by a human immigrant or a low wage worker overseas, for some reason the logic doesn’t work. One might ask why not just imagine that the migrant or the foreigner is a robot! In which case, everything would work just like adding a kiosk. The human is actually better from the perspective of creating jobs, because he needs to eat, a home to live in, etc., which means he creates demand for goods and services produced by other Americans. And the immigrant worker is more likely to need supervision from a fellow low-skilled human than a machine is.

Some politicians just go complete Luddite and say machines shouldn’t replace jobs at all, but Vance takes this weird position where having your job replaced is only harmful if the thing that takes it from you is conscious. So trade and immigration are bad, while technology is still good. We might call this the Qualia Theory of Economics. Doesn’t make any sense, but it’s a way to square the xenophobia of voters Vance appeals to with the techno-optimism of his Silicon Valley backers. Techno-optimist Vance is of course correct, while the nativist version is preying on the ignorance and anti-foreigner bias of voters in the Trump coalition.

The China Shock Literature

Nearly all economists are in favor of free trade based on the logic discussed above. They have always acknowledged that some domestic workers who compete with foreigners are hurt by removing barriers to commerce. But mathematical modeling – along with straightforward empirical research and economic logic – suggests that trade makes each nation better off in the aggregate. Note that this doesn’t depend on all countries “playing fair” or anything like that. If the US opened its borders to foreign goods and services unilaterally, that would be to the benefit of most Americans. But that’s not how things are done, and when the US granted most favored nation status to China in 2000, it did so on a reciprocal basis, with China lowering its own tariffs and barriers in return, marking the beginning of a new era of mutual market access between the two economies.

As it turned out, the Chinese were really good at manufacturing.

This is actually not as impressive as it looks, since China’s share of world exports is pretty similar to its share of the global population. Nonetheless, going from in effect not trading with other countries at all to claiming approximately a sixth of the global export market created a great deal of competition for the rest of the world.

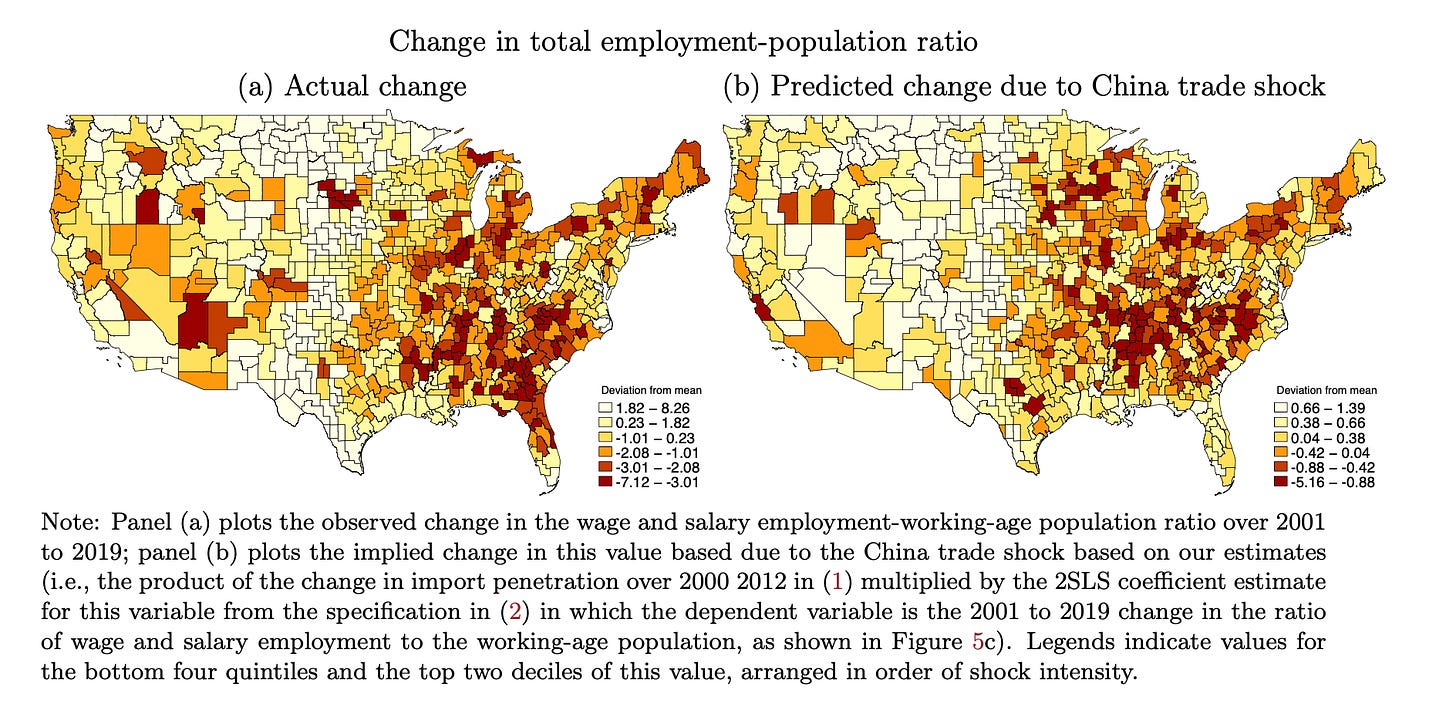

If you listen to nativists on the China Shock literature, you might think that it argues that this was a bad thing for the American people. But this is not the conclusion of this research area. Rather, scholars have argued that trade with China hurt certain communities more than previously thought. The landmark paper in this literature was “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States” (2013), by Autor, Dorn, and Hanson (ADH). They then followed this up with “On the Persistence of the China Shock” (2021). Both of these articles looked at what happened to wages in areas of the US that faced direct competition from Chinese imports.

The authors start by breaking the country up into over 700 Commuting Zones (CZs), which are “clusters of counties that are characterized by strong commuting ties within CZs, and weak commuting ties across CZs.” Of course, each CZ differs in how much manufacturing employment it has in sectors subject to Chinese competition. And if manufacturing declines in a CZ, you can’t just assume it is due to jobs being taken by the Chinese, since there might be demand related reasons, like for example the invention of a new product that renders an old one obsolete. ADH therefore construct a variable for how exposed to competition each CZ is by looking at the composition of manufacturing employment within each CZ and accounting for an increase in Chinese exports in advanced markets other than the United States. For example, if you have an area that makes luggage, and China has been exporting a lot of luggage to other developed countries, your region presumably faces a lot of direct competition from Chinese imports. At that point, you can see what the effects are within each CZ on variables such as crime, welfare dependency, unemployment, and wages.

ADH do indeed find that places exposed to Chinese competition suffered higher unemployment and lower wages, and these effects last for decades. In “On the Persistence of the China Shock,” ADH quantify the impact and show that, depending on which estimate of national gains from trade one uses, between 6.3% and 32.8% of the continental US population in 2000 lived in CZs that experienced net welfare losses from trade with China over the following nineteen years. Note that it’s not necessarily the case that any of these places got poorer in absolute terms. Rather, a significant portion of the US population, up to a third, lived in areas in which they were overall losers – compared to how wealthy they would have been otherwise – due to trade with China. Regardless of what estimates you use, however, the economists who brought attention to the negative effects of openness to Chinese manufacturing agree with the rest of their profession that it made the US better off overall, and that most Americans lived in areas that had improved living standards as a result. To take another estimate balancing the gains and losses from trade with China, Jaravel and Sager calculate an increase in US consumer surplus by about $400,000 per displaced job between 1998 and 2019

We must also note that scholars generally do not argue for protectionism based on the China shock literature. Writing in 2021, ADH warn readers not to become MAGAs or Bernie Bros as a result of their research, directly calling out the first Trump administration for abusing their work.

The favored solution of populist politicians to regional distress is to raise import barriers and block immigration. Indeed, the Donald J. Trump Administration cited the adverse impacts of the China trade shock to justify taking aggressive trade action against China (Redding, 2020). The subsequent U.S. China trade war succeeded in elevating U.S. product prices (Amiti et al., 2019; Fajgelbaum et al., 2020; Cavallo et al., 2021) but not in expanding employment in import-protected sectors (Flaaen and Pierce, 2019). We are aware of no research that would justify ex-post protectionist trade measures as a means of helping workers hurt by past import competition.

In 2016, David Autor told the New York Times that he still favored free trade. Instead of protectionism, ADH support targeted assistance to those left behind. They even stress that their preferences here don’t just apply to trade, but can be relevant to any shock to the labor market, including technological ones. This is another example of how economists see equivalency between job loss due to technology and job loss due to foreign competition, while politicians treat these as completely different things.

Basically, all economists agree that trade with China has been good for the US. They’re just debating the degree to which there were concentrated harms. And even the ones who think the harms were large reject protectionism. This is true even though if you hear a politician or pundit cite the China shock literature today, it is often to argue in favor of tariffs.

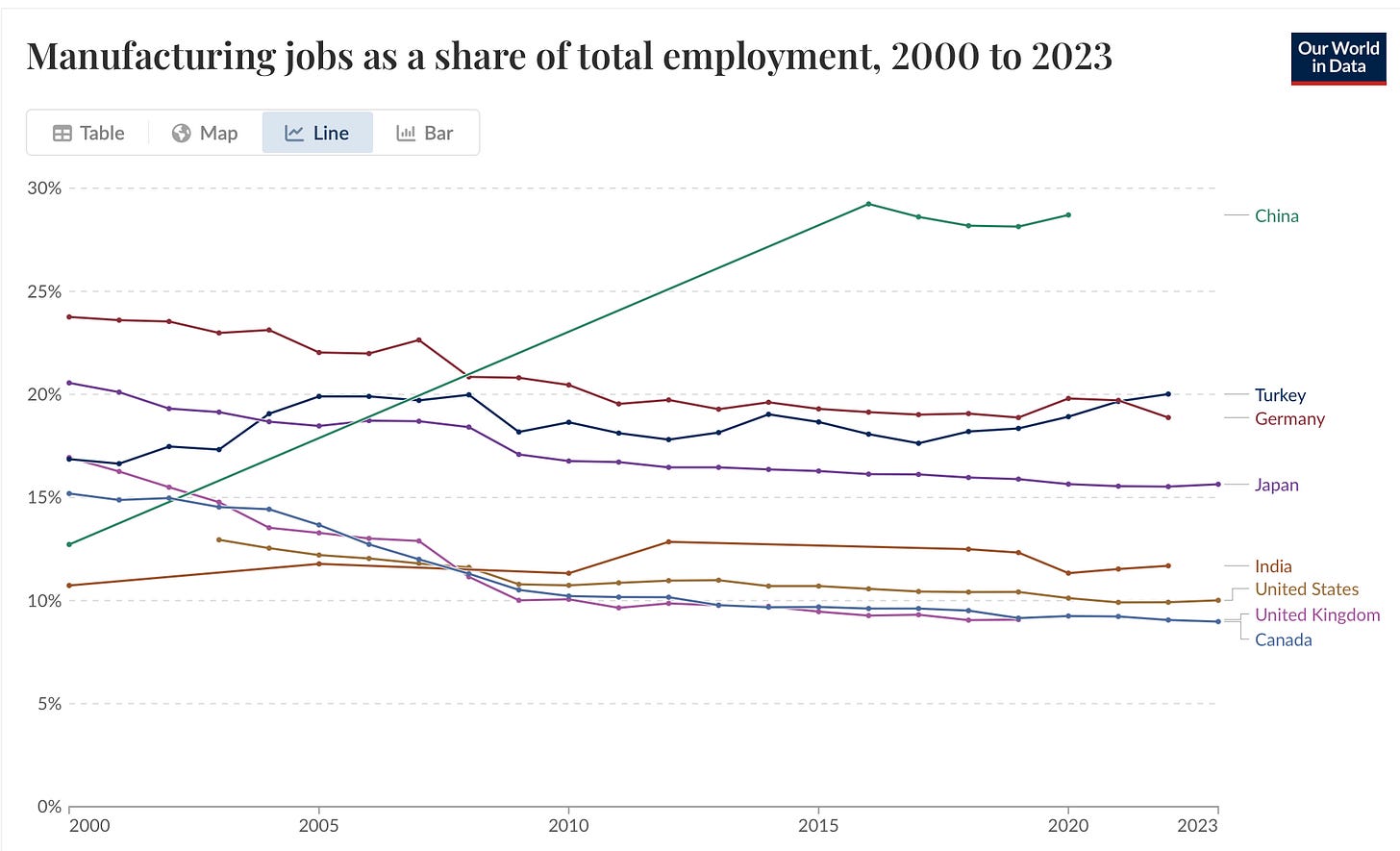

One more thing to note here is how crazy it is that we’re so obsessed with this one type of work. Here’s a chart showing percentage of jobs in manufacturing for select countries between 2000 and 2023.

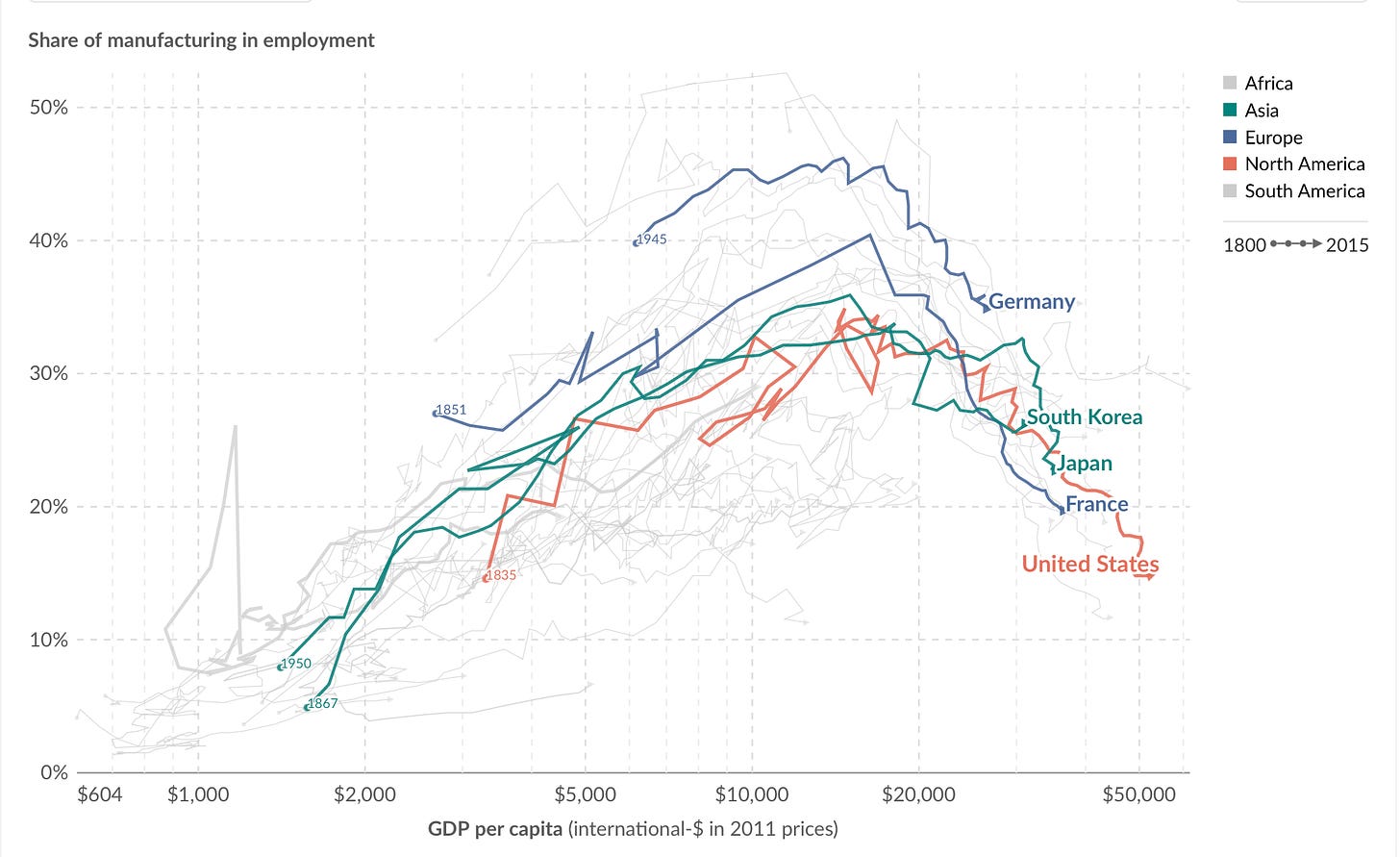

The US is at 10%. There is basically a universal pattern where countries see an increase in manufacturing jobs as they get wealthier, but then the numbers decline, in an inverted U-Shape.

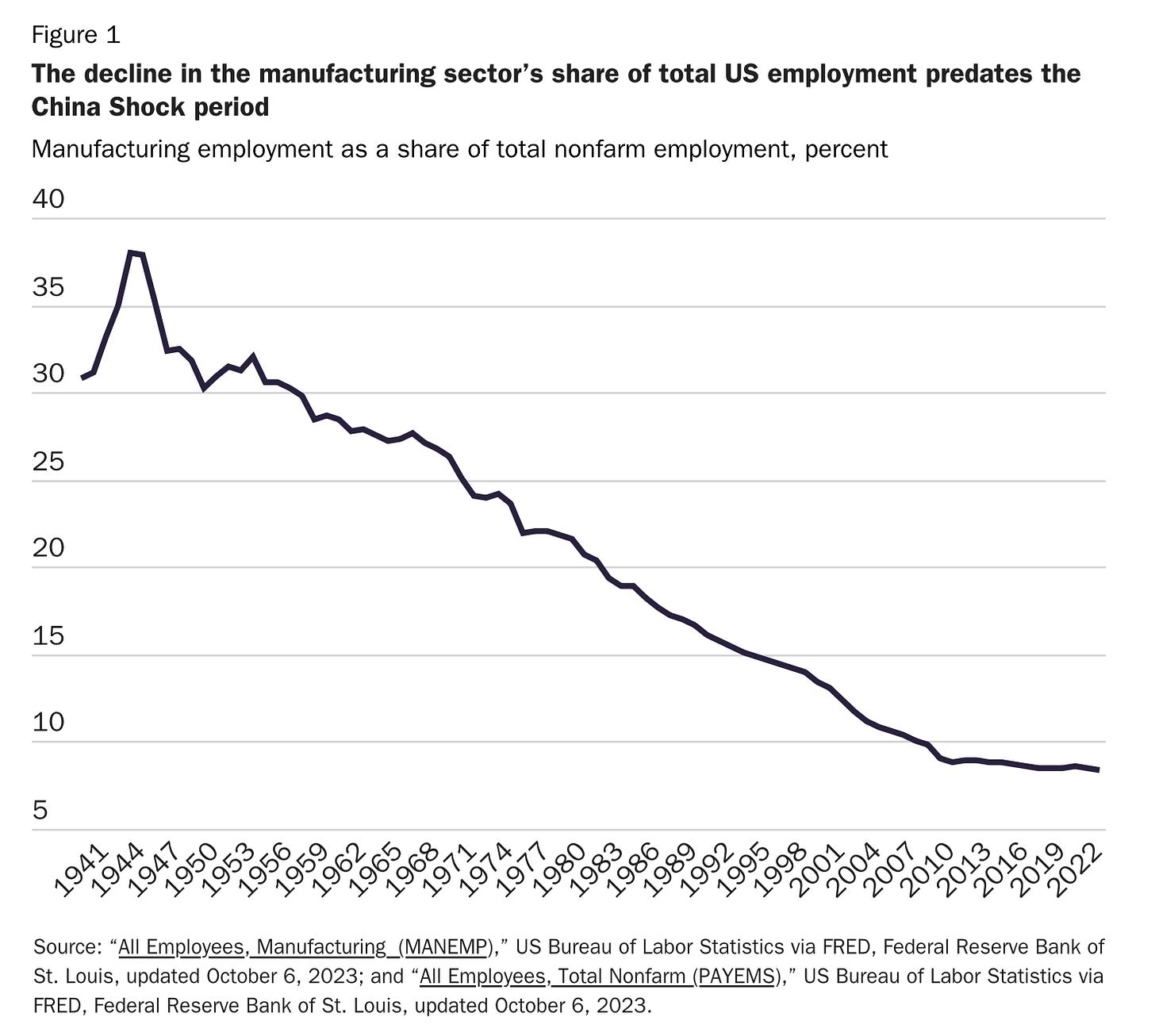

Of course the US doesn’t employ a lot of people in making physical objects these days! Manufacturing is highly automated, and we’re a rich country because most jobs are services, such as doctor, lawyer, or programmer among the white collar professions, and barber, garbageman, and Uber driver among the working class. The fact that so much of the discourse is obsessed with growing manufacturing jobs, with Trump making it the center of his economic program, shows how fundamentally irrational our politics is. People have this image of a prototypical job in their head, and it’s a guy working for Henry Ford on the assembly line. But this just isn’t what most people do in a modern advanced economy. To look at it another way, here is the US share of manufacturing jobs from 1939 to 2022. The China shock appears not to have been anything special, but rather the continuation of a long run process.

If there’s a policy that makes 67–94% of areas in the country better off, and causes an overall net improvement for the nation in the aggregate, you take it every time. If your standard for a policy is that it has to make literally everyone better off, you will never do good things, and American living standards will stagnate. I don’t see any particular reason to compensate the losers either, as if every good policy that goes in a pro-market direction can only be justified if it is wedded to new forms of redistribution, government will grow indefinitely. One might ask why people who benefit from protectionism never have to compensate consumers for profiting off their loss. There is nothing particularly special about factory workers losing jobs to Chinese competition that requires us to make up for new policies that benefit Americans in the aggregate. I could imagine someone arguing that doing so might be smart for political reasons – to tamp down some of the anger over the negative effects of free trade – but I think there’s little in American history to suggest that the recipients of welfare become less bitter upon getting government benefits. The opposite appears closer to the truth, as it legitimizes grievances and gives people something to blame for their problems.

It is better to just keep doing things that benefit say 70% of the country, and there’s no reason to think that it’s going to be the same 30% that is harmed each time. If you’re worried about the distributional effects of free trade policies, the Americans who benefit are disproportionately poor, because they spend a higher portion of their incomes on consumer products. Again, not many people work in manufacturing in the first place. This isn’t surprising, as there are plenty of pro-market reforms that can disproportionately benefit the poor, like removing occupational licensing requirements and restrictions on building housing. Not doing good things because someone somewhere might suffer is a terrible way to approach public policy.

Some Regions Must Lose (Relatively)

The US is a land full of opportunities and natural beauty. These things are overwhelmingly concentrated on the coasts and in Southern states that have taken the most laissez-faire approach to economic policy. There is no particular reason we should want more Americans living in Appalachia or the Midwest, which unlike the coasts aren’t building anything that humanity can’t get cheaper elsewhere. If the market is left to its own devices, it will funnel workers to places that have good weather and high-paying jobs.

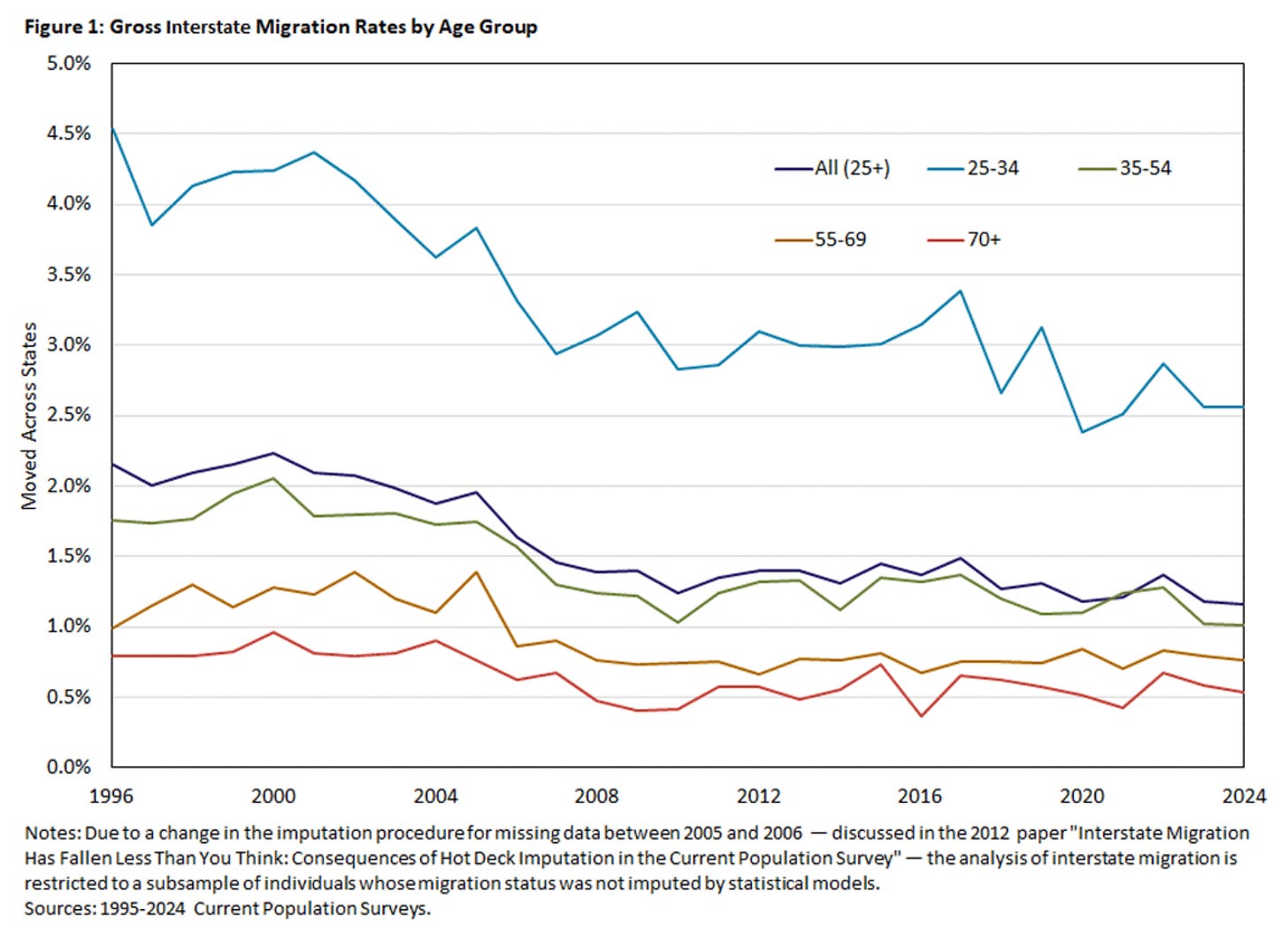

ADH stress that empirically, we do not see that many people move away from places that are economically declining. So if your argument is that trade doesn’t harm many individuals because they all just move, that is not necessarily the case right now. Part of this is likely due to out of control housing costs in urban metros, where there are opportunities for higher salaries, but at the same time, rent and mortgages make moving prohibitive for many. The welfare state also makes individuals comfortable and allows them to sponge off government. This is another reason to disagree with ADH on a need to direct more help to people experiencing economic shocks. If we do that, then maybe we should subsidize them moving, as geographic mobility is on the decline.

I see no reason to doubt that housing costs are a huge part of this. If YIMBY reforms succeed, then, like the China shock, they will contribute to the relative decline of the Midwest and much of the heartland. And like the China shock, that will still be good for the country as a whole. Giving someone benefits is feeding them for a day, having them move to a more economically dynamic area is teaching them to fish.

Most economists prefer direct redistribution. They complain about the effects of trade in order to get a larger welfare state. Meanwhile, politicians argue for protectionism and saving jobs, or bringing back jobs that are long gone. If you must do something, the economists have the better argument, though I would still oppose them on this point. But people like the idea of creating jobs and dislike the idea of welfare, so we get dumb populist policies instead.

Some foundational thinkers on the right like Pat Buchanan and Sam Francis have argued for protecting jobs on conservative grounds. Here they might cite Buckley’s famous maxim about “standing athwart history yelling stop.” Yet I think this is a dumb understanding of conservatism. It makes no sense to freeze everyone in the jobs and the local communities they are now in. Modern protectionism is even sillier than that, promising to return manufacturing to certain regions that have no comparative advantage anyway. If you were going to bring manufacturing to America, it would overwhelmingly be concentrated in the more free-market South. That’s where many of the jobs went anyway, as employers have fled more union-friendly states. But even more so the jobs went to machines.

A better version of conservatism doesn’t mindlessly try to freeze everything in place, but rather sticks to the principles of the Anglo-American tradition, based in liberty, limited government, and a faith in market processes rather than bureaucratic planning to order society. Technological progress is the basis of improvements in global living standards, and it depends on creative destruction. Free trade is part of the same process. Just picture Deng Xiaoping as an entrepreneur who opened a factory with over one billion robots ready to do the bidding of Americans, while also sending their dollars back in the forms of investment and purchases of other goods and services.

I’ve been saying for years that anyone, from either party, telling voters that manufacturing jobs are coming back because of this or that policy, is committing a heinous act equal to telling a child that their terminally ill parent is gonna pull through.

"One more thing to note here is how crazy it is that we’re so obsessed with this one type of work."

It's because it is perceived as being particularly good for relatively stupid, unsophisticated men. Or "real men" as people who romanticize such men probably consider them. The populist right frets over relatively stupid, unsophisticated men the way the woke left frets over black people.

There's also lingering romanticizing of them on the left because the left still traffics in stupid Marxist ideas, often without even realizing it. In this case, the working class isn't just the people you are trying to save from capitalist exploitation, but they are the demographic possessed of some magical gnostic wisdom that will let them overthrow the capitalist order and then something something utopia. This is the central problem/paradox of Marxism. It's supposed to rally the industrial working class, but the industrial working class largely doesn't care about this, and the radicals you actually get are educated elites and literal peasants who want land redistribution. Communist revolutions happen in peasant quasi feudal societies, not industrialized ones.

Meanwhile, normies are populist in general and picture cliche imaginary assembly line man with a Ford, a picket fence, a housewife, two kids, and a dog as being "someone like me" as opposed to tech bros or finance bros or whatever. I think the reason they fixate on this meme in particular instead of, say, truck drivers or construction workers is literally just advertising. People also romanticize antiquated farming practices for similar reasons. The supermarket has pictures of big red barns and spotted cows grazing in green grass, not CAFOs or vat grown beef. Meanwhile, nobody thinks cottage garment production is romantic. You don't see pictures of happy peasant women in a knitting circle in the clothes department even though such imagery is also nostalgia inducing.