If you look at almost any kind of cross-national data, you notice that East Asians are fundamentally different from other peoples. So much so that we might talk about an “East Asian package,” a series of traits shared by South Korea, Japan, China, and the Chinese-descended nations and territories of Hong Kong, Macau, Singapore, and Taiwan. There are indications that even North Korea shares many of its important components, despite it being the most isolated country in the world. This package includes:

Low levels of crime. Every East Asian country, with the possible exception of North Korea, where we lack data, has a murder rate of less than 1 per 100,000. This is true whether you look at China and its 1.4 billion people, other sizable nations like South Korea and Japan, or the crowded city-states of Singapore and Hong Kong. The latter category is particularly notable because American liberals often respond to complaints about crime by saying that it is a natural part of living in a big city. But the largest and most crowded East Asian cities have less crime than rural and suburban areas in the West!

Extremely low rates of illegitimacy. Below you can see countries ranked by percentage of children born out-of-wedlock. Japan and South Korea are at the bottom, somehow below Turkey and Israel, thus making them closer to the Middle East than Europe in this area. Taiwan isn’t usually included in these cross-national comparisons, but it’s similarly low. I can’t find numbers for China, but I would be shocked if things were any different there.

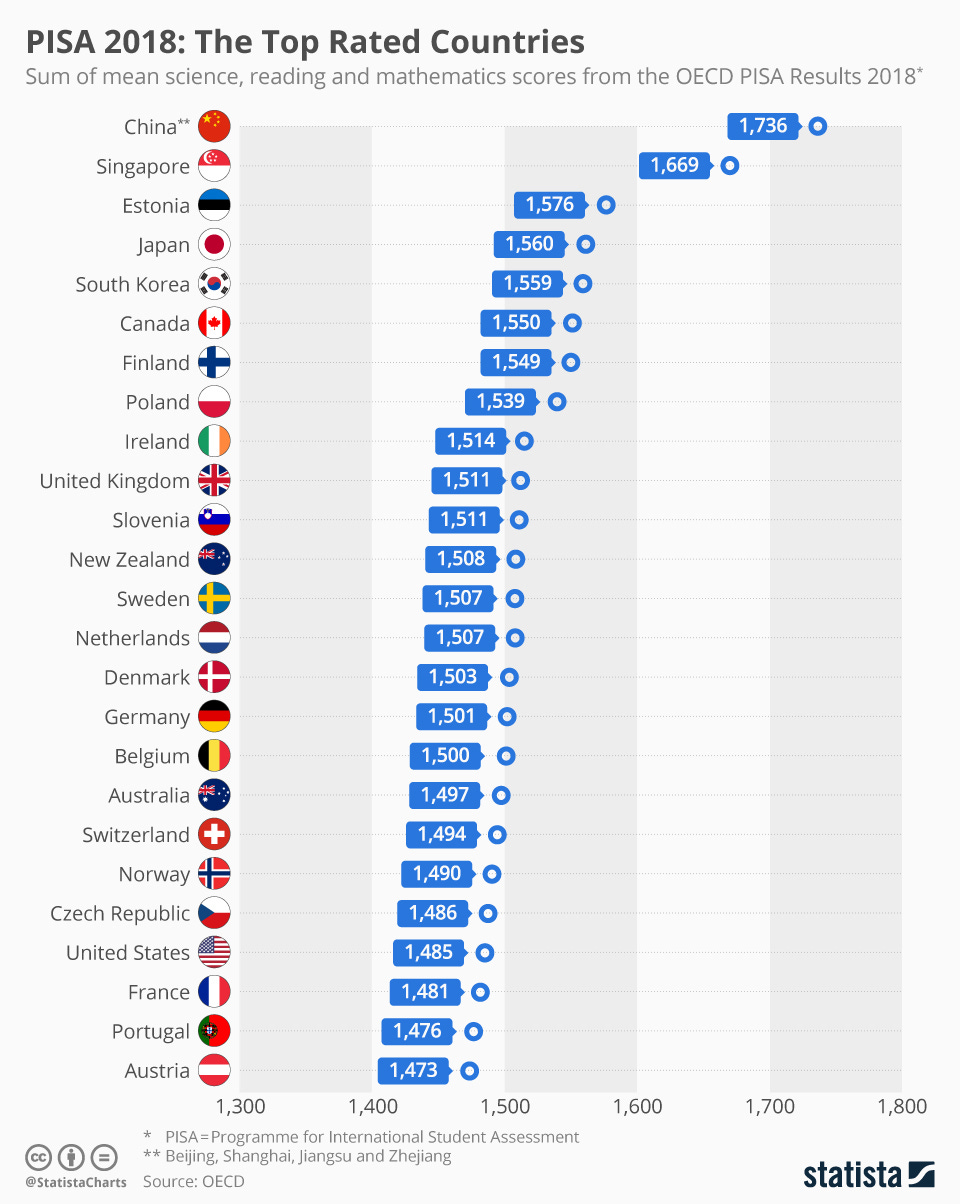

High levels of academic achievement, particularly in math and science. You can see the 2018 PISA results below. Some people think the Chinese numbers here can’t be trusted because they only tested urban centers, but we’re still talking about kids who are coming from families that are poor by Western standards. North Korea doesn’t show up in international comparisons, but it actually fields a formidable Math Olympiad team, and has constantly shocked Western analysts by how quickly it’s been able to develop advanced military technology. The East Asian aptitude for math and science is reflected in it being the only non-Western part of the world to produce multiple major tech giants, including familiar names such as Samsung, Mitsubishi, Sony, TSMC, and Alibaba.

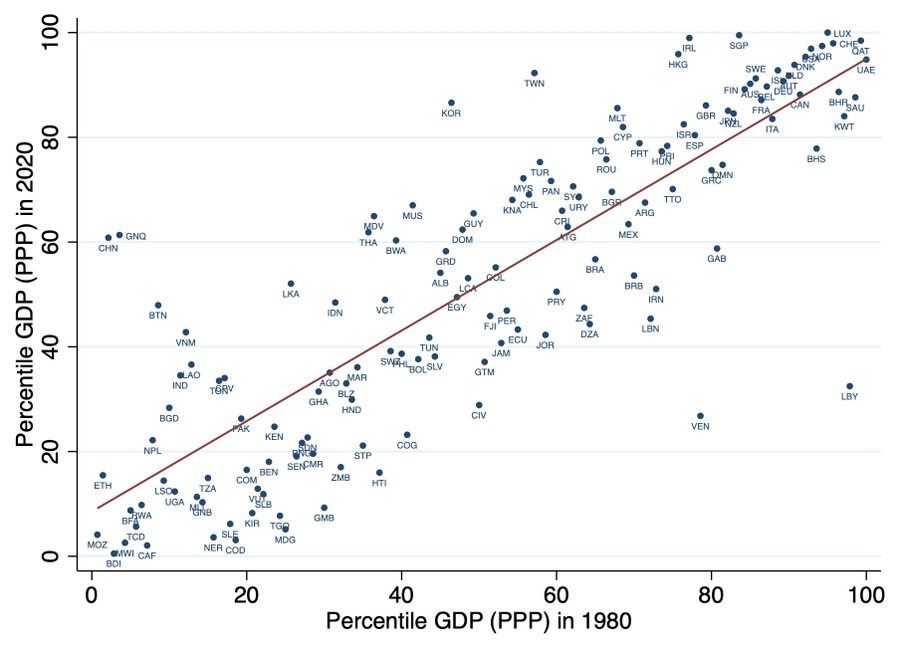

High levels of economic growth in recent decades. I’ve put together this chart showing relative change in GDP per capita between 1980 and 2020. The top five best performing countries includes three in East Asia: China, South Korea, and Taiwan. There’s a book called How Asia Works that tries to attribute this to East Asian nations adopting the correct developmental policies, but as Scott Alexander points out, “It seems weird that all the countries with good policies would be right next to each other.” Indeed, many of the policies the author suggests, like land reform, have been tried outside the region with limited success. Even if the book could explain economic development, it doesn’t explain East Asian success in other countries, nor the rest of the East Asian package.

Extremely low fertility. South Korea keeps setting new records in this area. The country with the second lowest fertility in the OECD is Japan. If Taiwan was considered its own country, it would be challenging South Korea for the world record. Meanwhile, China isn’t even that wealthy yet and its birth rate has already cratered, having fallen behind Japan. While East Asians weren’t always infertile, indicating that this isn’t an immutable trait that exists independent of cultural and historical circumstances — we did somehow end up with 1.4 billion Chinese, after all — the nations of the region have without exception responded to economic growth and modernity by being much less likely to start families, and the extent of the collapse isn’t like anything we’ve seen anywhere else in the world.

High life expectancy. According to World Bank data, the top five countries or territories with the longest life expectancies in 2020 were Hong Kong, Macao, Japan, Singapore, and South Korea. Part of this was because the region had fewer covid deaths, but the results weren’t too different before the pandemic.

What’s really amazing about all of this is that these countries are extremely different by most conventional measures of how we understand and classify nations. China is an authoritarian state and about at the middle of the pack when it comes to income and its urbanization rate, while South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan are all developed and urbanized democracies in good standing. As mentioned before, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Macau are basically just cities, though we have numbers for them and can study those places in the cross-national context.

Moreover, you find the East Asian package outside of East Asia, among people of East Asian descent. In the US, Asians famously get higher test scores than whites, and are so successful that the affirmative action debate centers around whether schools can keep trying to stop them from becoming too large a portion of the student body. This is similar to the politics of many Southeast Asian countries, where Chinese success is a constant source of tension with lower-performing natives. In the UK, Chinese students have the highest test scores of any ethnic group. The Japanese are considered a “model minority” in Brazil. One could go on.

You’d think social scientists, if they were serious people, would treat this as one of the most important things they could be studying. We all want a longer life expectancy and less crime, and reducing illegitimacy and getting test scores up are forever goals of public policy. We have a major region of the world that is filled with extreme outliers on all of these measures. If there was a country with nearly no cancer, wouldn’t medical researchers want to know why that was? Why is it so uninteresting that an entire region of the globe seems almost completely free of the social pathologies that afflict much of the rest of the world?

The Failure of the Cultural Explanation

I never see liberals talk about the East Asian package, except when they’re arguing with their fellow leftists and trying to debunk some misconceptions they hold, in effect making a conservative argument. Conservatives and moderate anti-wokes, in contrast, like to talk about Asians, since their success seems to refute the liberal worldview. Amy Chua, for example, has famously argued that cultural differences explain which ethnic groups in the US succeed.

But do Japan, China, and Korea in fact share a common culture? People sometimes make this point in a circular way. The fact that East Asians behave similarly across various countries and social contexts supposedly indicates that they belong to the same culture. A group that does well on tests “values education,” while one that doesn’t have children out-of-wedlock has “conservative social values.” We might as well say differences in crime rates reflect how much various communities “value crime.” Such explanations are useless.

But is there a non-circular way to approach the topic? I think there is, and once you do, you struggle to find evidence that China, Korea, and Japan have all that much in common culturally. Without falling into the trap of circular reasoning, we can measure cultural distance or similarity by the following criteria.

Religion. We often say that peoples that share a religious faith belong to the same culture. About 70% of Japanese practice Shintoism, a religion that exists in no other country in the world. A similar number of Chinese either have no religion or practice “Chinese folk religion.” Meanwhile, in South Korea, a quarter to a third of the population is Christian, a faith that barely exists in Japan or China. All three countries have sizable Buddhist populations, but they each practice the religion in ways that reflect their own independent cultural histories. There has certainly never been anything equivalent to the Catholic Church in Europe, that is, a centralized spiritual authority for the region.

Language. Linguistic similarity and relatedness tend to correlate with closer cultural affinity, both because close languages allow for communication across political boundaries, and indicate that people belonged to the same community not that long ago. Linguists put languages into family trees, based on the theory that the major families of the world each represent an ancient proto-community. All forms of Mandarin are part of the Sinitic branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family. Meanwhile, when I studied linguistics as an undergrad, Japanese and Korean were said to be “language isolates,” meaning they had no known relatives, although Wikipedia tells me that they are now considered part of the “Japonic” and “Koreanic” families. Some scholars have proposed something called the Altaic family, which would encompass Japonic, Koreanic, Turkic, and Mongolic languages, but this appears to be a minority view. In other words, although East Asian languages have shared loan words over the centuries, Mandarin is at its core as distant from Japanese or Korean as English is from the indigenous languages of Australia. Korean and Japanese are either just as distantly related, or share a common origin so deep in the past that most linguists doubt that they should even be grouped together.

Political history. As mentioned above, China is a dictatorship, while Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan are democracies. Singapore is somewhere in between. Japan has been an independent unified nation for over 400 years, and has had a parliament or some form of representative government since 1889. It generally has been extremely xenophobic and closed off to outsiders. The Joseon dynasty of Korea (1392-1897) was so isolated from the rest of the world that Western scholars named it the “Hermit Kingdom.” China under Mao underwent one of the greatest social upheavals the world has ever seen, and it now has a very unique political system. It’s true that Japan briefly colonized Korea and Taiwan, but this was an exception to a long history in which the three major peoples of East Asia had relatively little contact with one another and lived under different kinds of governments. Even if East Asians did start out sharing the same culture, it’s hard to see how the events of the last 150 years, from the Meiji Restoration to World War II and Maoism to democratization across much of the region, wouldn’t have caused divergence given the different experiences of these nations.

Moral psychology. According to Joe Henrich, writing in The WEIRDest People in the World, Japan has “a unique social psychology, distinct not only from WEIRD societies but also from populations in South Korea and China, with which it’s often mistakenly lumped together with psychologically.” Even placing South Korea and Chinese-derived countries and territories together strikes me as a stretch based on the data. Check out this famous chart based on the World Values Survey. It’s gerrymandered in a way that would make a Republican state legislator blush. All East Asians get grouped into the “Confucian” category, despite China being closer to Belarus than it is to South Korea, and Japan being as close to Protestant Europe as it is to its neighbors. Given how distant China is even from Taiwan and Hong Kong, one could argue that it would be too much to grant that all Chinese-derived nations and territories have a similar culture.

Pop culture. Japan and South Korea have produced pop cultural products that have large fan bases abroad. China has not, remaining unattractive to outsiders, or as Peter Thiel calls it, “weirdly autistic.” And although I’m no expert in either, from my limited experience K-Pop and Japanese anime strike me as fundamentally reflecting different values and cultures.

Attitudes towards sex. South Korea is by almost any measure a socially conservative country. It bans pornography, while Japan is known for being extremely creative in this area. Until very recently, South Korea prohibited most abortions and even adultery, with change only coming through court decisions. China is of course even more socially conservative, and has zigzagged from an emphasis on gender equality during the Mao era to the Xi government declaring a war on sissies and telling women that it’s gross for them to remain single over 30.

If having a similar culture doesn’t mean being similar in terms of language, religion, moral psychology, political institutions and history, pop culture, or sexual attitudes, what could it mean? Again, one can’t define “cultural similarity” in terms of things like high test scores and low levels of crime and illegitimacy, as that’s what we’re trying to explain in the first place.

We can see how culturally separate East Asian nations are from one another by imagining what a similar exercise would look like for Europe. Here, using the same methods, we can find strong evidence for cultural connections. With a handful of exceptions like Hungarian and Basque, all languages of the continent belong to the Indo-European family, broken down into categories and subcategories like Germanic and Slavic. All countries have historically been overwhelmingly Christian and except for Belarus and Russia all are democracies. Finally, European history can be understood as a series of consolidations and fragmentations of various empires, from Rome to the Soviet Union. The idea of united Europe, or Christendom, has been strong enough to inspire major political projects, as varied as the Crusades and the EU. For centuries, Europeans have seen themselves as part of one community, with political, social, and scientific ideas easily permeating across ever shifting state boundaries. In contrast, in East Asia there has never been a strong idea of an identity that encompasses Japan, China, and Korea and separates their civilization from those of other peoples, or at least nowhere near to the same extent. Thus, while it makes sense to speak of a European culture, the idea of an “East Asian culture” seems like a convenient shorthand used to arrive at a quasi-explanation of why countries that happen to be next to each other have similar outcomes. Europe is even more of a coherent concept in the World Values Survey cited above, unlike the gerrymandered East Asian category.

None of this is to say that some ideas like Confucianism and Buddhism haven’t crossed the borders between China, Korea, and Japan. Only that political, social, religious, linguistic, and other kinds of links between the nations of the region have been extremely tenuous and weak compared to Europe, and also other parts of the globe we consider broad civilizations like the Indian subcontinent and the Muslim world.

Global Stereotype Threat

Liberals believe in “stereotype threat,” in which our expectations and perceptions regarding how groups behave become self-fulfilling prophecies. We’ve seen that cultural explanations for the East Asian package favored by conservatives don’t make much sense, so maybe liberals are on to something.

As Ibram Kendi and other modern scholars argue, racism is an all-pervasive force that can explain practically every group outcome within the United States. He teaches us that, “To be antiracist is to deracialize behavior, to remove the tattooed stereotype from every racialized body.” While Kendi’s analysis is limited to the American context, how much of a stretch is it to think that such forces can operate on a global scale?

Granted, stereotype threat as a way to understand the East Asian package has certain difficulties. It would need to explain how stereotypes operate globally, across cultural, linguistic, and political barriers. Somehow, a Korean in Los Angeles and a descendent of Japanese immigrants in Brazil must both know that Westerners expect them to have a certain collection of traits. This influence of stereotypes even penetrates foreign countries, including China, despite the best efforts of the government to keep its population culturally isolated from the outside world. Of course, Xi Jinping is no match for the power of global stereotype threat, given that it even made North Koreans good at math. Kendism may also need stereotypes to travel back in time to work since East Asians somehow were already wealthy in the US decades ago, despite China being associated with crushing poverty throughout most of American history. But these are small details for Kendism, an ideology so convincing and scientifically well-established that universities produce glossaries to teach its core tenets.

Say what you will about Kendi, but he’s given us a framework that can possibly explain the East Asian package. Can it be a coincidence that we see the highest levels of economic growth and mathematical success, and lowest levels of illegitimacy and other forms of anti-social behavior, in countries that are geographically adjacent, despite the limited cultural links between them? And that people from these countries show similar traits when they move abroad? Journalists and academics write papers about low South Korean fertility or remarkable Chinese growth over the years, or about Asian success in American schools, and look for local factors at work, without seeming to understand that they’re observing any kind of broader phenomenon. It’s like if scientists were trying to figure out the association between elevation and weather, and were coming up with an independent hypothesis about the relationship on each continent without ever attempting to synthesize various kinds of data into a more general theory.

Given that conservatives and anti-wokes more generally have done such a poor job of presenting a theory that fits what we see in the world, it is no wonder that Kendism has unrivaled influence. With our advanced modern state of understanding of social phenomena, it remains the only school of thought that has broad explanatory power.

Commenters here chastising Richard for ignoring genetics is truly beautiful.

The East Asian countries in question all have a history of strong (compared to their central and southeast Asian neighbors) central government. They also have a history of literacy. And they aren't independent: the origins of both the Japanese and Korean legal traditions lie in the Chinese classics.