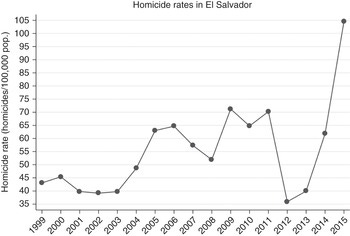

There were two objections I saw to my recent piece on the invisible graveyard of crime. I didn’t see anyone seriously quibble with the back-of-the-envelope cost-benefit analysis. Rather, people raised the question of whether the Bukele crackdown actually worked as advertised. First, some people looked at the graph below and noted that the murder rate had been falling since 2015, when it was at an astronomically high 103 per 100,000.

In 2018, the year before Bukele came into office, it had already dropped to 51 per 100,000. How reasonable would it be to assume the number would’ve continued to fall until it reached something like 7.8 even in the absence of a gang crackdown? We might begin by checking historical trends in El Salvador. Here’s what we find.

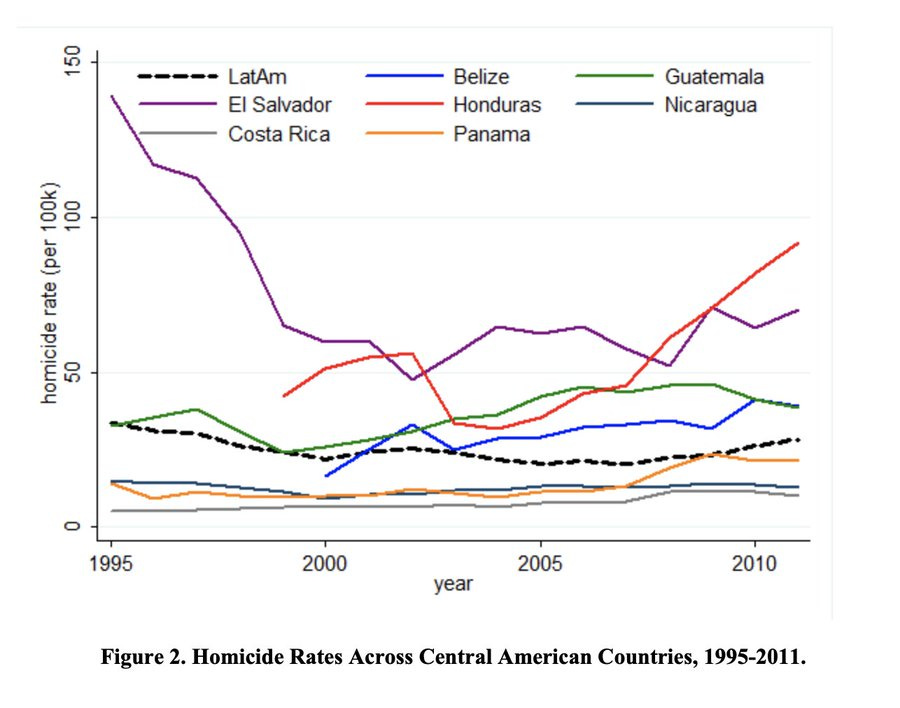

According to this source, between 1995 and 2011, El Salvador went from a murder rate of over 100 to fluctuating in the 50-75 range. Another estimate has the number at around 40 in the early 2000s, but tells a similar basic story.

All of this means that when Bukele came to power in 2019, the murder rate was within the historical norm as judged by the last three decades.

The assumption that “things tend to revert to the mean” is a much better assumption than “trends continue until they reach numbers never seen before.” For example, let’s say you have a typical summer day in late July. The next day, the temperature drops 5 degrees. It would be pretty stupid to extrapolate and say that it’ll keep getting colder until you have snow in August. To make an analogy more directly to the point, the murder rate in the US increased by 30% in 2020. It wouldn’t have made sense to assume that would keep happening each year until after about a decade the US becomes more violent than the most dangerous Latin American countries. I’ll make a prediction that the US murder rate in 2030 is going to be somewhere between the highest and lowest level it’s been since the 1960s. If by that time our numbers look like Honduras or Japan instead, something important would’ve had to change.

In sum, the 2022 murder rate of El Salvador is so far outside the historical norm that it cries out for an explanation.

This leads to the second argument I’ve seen, which is that Bukele simply worked out a deal with the gangs. That case was made in a National Review article, and by Matt Yglesias on Twitter.

If this theory were true, it would beg the question of why no other government ever worked out a deal that could get the Salvadoran murder rate down to the single digits. But as someone on Twitter pointed out, it appears that the agreement with the gangs broke down in early 2022, and they went on a killing spree. This led to the current crackdown, with the murder rate finally plummeting to a new historic low. It looks like the “deal” that finally worked to make El Salvador a safe country was the government saying to criminals “we’re going to lock you all up and not worry about human rights norms.”

I think what we have here is a classic case of the midwit meme.

What was happening before 2022? Human rights organizations were already complaining that Bukele was being too tough on criminals in 2020. Any agreement that was made between gangs and the government has to be understood in the context of a state that was starting to take public safety seriously, which likely gave it leverage in any negotiations, and may have been what caused the deal to break down in 2022.

Here’s an article from 2020 on the “carrots and sticks” approach the government was taking.

Locals offer two very different reasons for the extraordinary security achievements of Bukele’s government. The president and his cabinet claim that full credit belongs to their “Territorial Control Plan,” the government’s as yet unpublished and largely secretive stick-and-carrot strategy, combining “iron fist” law enforcement measures with incentives for youngsters in low-income communities to stay away from gangs. As in many other Latin American countries, mano dura (iron fist) is enduringly popular, offering voters the assurance of unsparing punishment and mass incarceration for criminals even though it repeatedly fails to curb violence over the long run.

Under the plan, the government uses its control of El Salvador’s jails, among the most overcrowded in the world, to pressure gang members who remain free. The authorities threaten that if gang members still on the streets don’t curb their use of violence, the government will step up punishments and harsh confinement of those inside prisons, appealing to gangs’ camaraderie and to the deadly perils that gang members could face if they don’t defend the interests of their jailed leaders. The government delivers this point in simple, direct statements, and has used pictures of stripped and jailed gang members to drive home the message. “Stop killing immediately or those who will pay the consequences will be you and your homeboys,” read one tweet from Bukele in April.

His threat followed a sudden spike in homicides, which rose from two per day to 85 in a five-day span. The government’s response to the killing spree was so harsh that it gained international attention. “No light beams will enter,” warned Osiris Luna, head of the national penitentiary system, as he laid out the new prison rules. Members of rival gangs would share the same cells for the first time since 2004 (when they were separated by affiliation to avoid bloodshed). Cell doors and windows would be sealed, in compliance with presidential orders, so inmates could neither see the sky nor talk with inmates elsewhere…

But despite mounting evidence that the gangs and the government have been talking, there is much less reporting about “whom they’re talking to and what they’re talking about,” in the words of another former 18th Street gang member. The supposed process is shrouded in secrecy by both the gangs and the government, though some details have seeped out. El Faro’s report suggested that, as part of negotiations, the government had pledged to reverse the decision to mix members of different gangs in shared cells alongside other concessions. These included allowing fast-food deliveries to jails, transferring aggressive guards, and reportedly reforming gang-related legislation, should Bukele’s party win next year’s elections.

To be clear, the timeline here appears to be that, first, Bukele comes to power and institutes a crackdown. He then reaches a “deal” with the gangs, which involves relaxing the repression a bit by letting them have fast food, not letting prison guards abuse them so much, and not placing them in cells with rivals where they kill each other. The crime rate goes down. The deal collapses, at which point the government increases the level of repression and the crime rate plummets even further. At the end of this process, Western pundits tell us that repression doesn’t work, and attribute everything to Bukele being friends with the gangs. They ignore the fact that it was the tough-on-crime approach that made it an option to reduce the murder rate with cheeseburgers and curly fries in the first place.

The interesting question here is why people are so resistant to the idea that the crackdown is working. I think there’s a common mental trick where analysts are uncomfortable with the existence of a tradeoff, so they pretend it doesn’t exist. People like the idea of post-Warren Court civil liberties, and they don’t want to say “if it’s going to lead to a lot more death and destruction, so be it.” Instead, they convince themselves that repression can’t work. To me, it seems obvious that a lot of stuff we do in the US, like reading suspects their Miranda Rights and warning them not to say anything too incriminating, makes being a criminal a lot easier and solving crimes a lot more difficult. Yet people are attracted to a belief in a kind of karmic justice, in which the society that behaves in the least punitive way towards criminals ends up with greater safety and prosperity. That certainly hasn’t worked in Latin America, where governments, under American influence, tend to be more restrained and respectful towards the rights of the accused than in other parts of the developing world. It’s perhaps time to try the other thing.

It really seems like a significant portion of the American intelligentsia just doesn't understand—or wont admit—that in every society a small but non-trivial minority of men are both (1) highly prone to violence and causing havoc and (2) can't be "fixed" or rehabilitated and must be sequestered from society in one way or another.

I think you've nailed it. The pundit class in the Anglosphere simply doesn't do tradeoff thinking when it comes to issues that they find emotive. Civil liberties are a prima facie good, and since they're good they can't contribute to anything bad, and crime is bad, so civil liberties have no relationship with crime. That really is the sum total of the thought process.

You can apply it to so many things. COVID lockdowns. An unalloyed good. Their proponents wouldn't even countenance the damages to education and to the mental health of those who need high levels of socialization. It wasn't even "we are making this temporary tradeoff - there will be some costs, but the benefits outweigh them."

Politically this makes sense. Pointing out the flaws in your own plan is seen as weak, even if you believe your plan to have benefits that far outweigh those flaws. But I think because we don't speak this way and because we're not expected to speak this way, we also don't bother thinking this way. (Maybe this is backwards and the thought precedes how we speak.) My point is that I think much of our pundit classes and political classes have actually lost the ability to think about these tradeoffs at all, and that they are acting in the service of 100% good, 100% of the time, and that they genuinely can't anticipate any downsides to their chosen courses of action. It's a holy crusade all of the time.