The Weirdness of Government Variation in COVID-19 Responses

What has surprised me about the politics of the pandemic

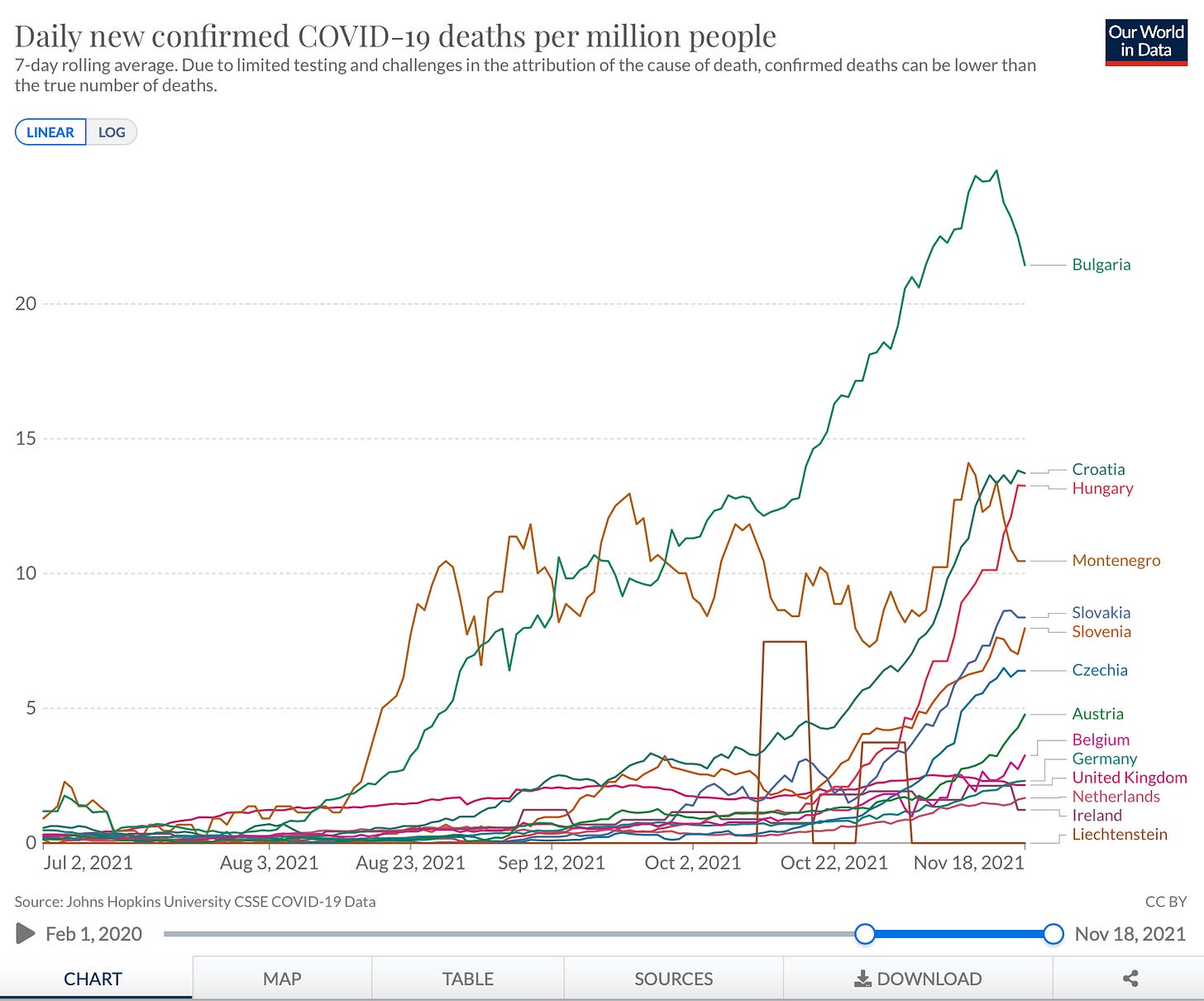

Austria has just gone into a 10 day lockdown, to possibly be expanded to 20, over COVID-19. Here is the state of the pandemic in various European countries.

Austria doesn’t have an unusually high number of deaths right now. It’s pretty high in cases, but even here it’s not an outlier. Slovakia and Slovenia are worse, while Belgium is catching up.

This illustrates something that has surprised me throughout this pandemic, which I haven’t seen anyone else discuss.

Usually, countries and regions that share a cultural legacy and the same political system don’t differ too much in the ways in which they respond to events in the real world. Like in Europe, the corporate tax rate varies from 10% in the lowest country to around 30% in highest. Basically every country in Europe likewise spends between around 0.2% and 2% on the military. Basic stuff like the number of hours kids spend a day in school, how to fight crime, etc. tend not to be that different across the continent.

But imagine at the start of the pandemic, someone had said to you “Everyone will face the existence of the same disease, and have access to the exact same tools to fight it. But in some EU countries or US states, people won’t be allowed to leave their house and have to cover their faces in public. In other places, government will just leave people alone. Vast differences of this sort will exist across jurisdictions that are similar on objective metrics of how bad the pandemic is at any particular moment.”

I would’ve found this to be a very unlikely outcome! You could’ve convinced me EU states would do very little on COVID-19, or that they would do lockdowns everywhere. I would not have believed that you could have two neighboring countries that have similar numbers, but one of them forces everyone to stay home, while the other doesn’t. This is the kind of extreme variation in policy we don’t see in other areas.

It’s similar when you look at American jurisdictions. Los Angeles County was the first major jurisdiction in the country to bring back mask mandates after they had been lifted everywhere in summer 2021. Meanwhile, Orange County, the next jurisdiction to the south, doesn’t have one. Before COVID-19, most Americans would have considered having to wear a mask in public a major infringement on liberty. I would’ve believed you if you told me that the presumption against such an extreme mandate could be overcome if things got bad enough, but again, like the EU, I would never have expected similarly situated neighboring American counties to adopt such radically different policies. LA County and Orange County are at the same level of community transmission according to the CDC.

Why do jurisdictions tend to have similar policies in most issue areas? There are certain laws of political gravity. Make the tax rate too low, and you can’t pay for all the government services people want; make it too high, people get mad and you start to destroy economic activity. Yet with COVID-19, it looks like governments can do whatever they want, and there isn’t much of a backlash in either direction.

I would’ve thought that people in LA County would go, “Isn’t that weird? I have a sister in Orange County where they’re allowed to show their faces in stores, and they seem to be doing no worse than us. I also have a cousin in Louisiana, and his kids don’t even wear masks indoors in school, while my children wear them when playing outside during recess. And they have even less transmission in their area. Maybe this whole thing is stupid and my kids shouldn’t spend half their high school years not knowing what their classmates look like?” Or, alternatively, people would be so freaked out by COVID-19, that those living in Orange County would see that LA County has a mask mandate, and go crazy demanding the same thing. Likewise, I would’ve never expected that Austria would shut down the entire country, while its neighbors Slovakia and Slovenia have objectively worse numbers but let life be mostly normal.

I would’ve thought that “whether I can show my face in public”, or “whether most businesses in the country should be forcibly shut down” would be the main political issues in each region or country, simply because the COVID-19 restrictions are such an outlier in the extent to which western governments have restricted freedom and disrupted people’s lives since the end of the Second World War. We see polling data on things like mask mandates and lockdowns, but to me what they say is less interesting than the fact that restrictions are not all we talk about and do not overshadow every other political issue.

For most people, their view on COVID-19 seems to be “whatever my government is doing right now must be right, or at least not a big enough deal to motivate me to try to change it or vote on it, like I might vote on inflation or critical race theory.”

What does this tell us about democracy more generally? As the political reaction to COVID-19 has surprised me, I’m still trying to figure it out. But for now I can say it’s shifted my priors in a few ways.

People are more conformist than I would have thought, being willing to put up with a lot more than I expected, at least in Europe and the blue parts of the US.

Americans in Red States are more instinctively anti-elite than I would have thought and can be outliers on all kinds of policy issues relative to the rest of the developed world (I guess I knew that already).

Partisanship is much stronger than I thought. When I saw polls on anti-vax sentiment early in the pandemic, I actually said it would disappear when people would have to make decisions about their own lives and everyone could see vaccines work. This largely didn’t happen. Liberals in Blue States masking their kids outdoors is the other side of this coin. Most “Red/Blue Team Go” behavior has little influence on people’s lives. For example, deciding to vote D or R, or watch MSNBC or Fox, really doesn’t matter for your personal well-being. Not getting vaccinated or never letting your children leave the house does, and I don’t recall many cases where partisanship has been such a strong predictor of behavior that has such radical effects on people’s lives.

Government measures that once seemed extreme can become normalized very quickly.

The kinds of issues that actually matter electorally are a lot more “sticky” than I would have expected. Issues like masks and lockdowns, though objectively much more important than the things people vote on, are not as politically salient as I would have thought. A mask mandate for children eight hours a day strikes me as a lot more important than inflation, but it seems not to be for electoral purposes. If an asteroid was about to destroy earth and Democrats and Republicans had different views on how to stop it, people would just unthinkingly believe whatever their own side told them and it would not change our politics at all.

Democratically elected governments have a lot more freedom than I thought before, especially if elites claim that they are outsourcing decisions to “the science.” Moreover, “the science” doesn’t even have to be that convincing, and nobody will ask obvious questions like how “the science” can allow for radically different policy responses in neighboring jurisdictions without much of a difference in results. This appears true everywhere in the developed world but in Red State America, where people really hate experts, regardless of whether they’re right or wrong.

Anyway, there isn’t much of a larger point here. I just thought it was worth thinking about how the pandemic has confounded my expectations, and would be interested in hearing what others think.

I'm surprised, given your other writings, you can't see some obvious factors here:

1. Complete manipulation of the narrative and the "data" by those who benefit from said narrative. This includes people in media, government bureaucracies, pharma companies.

2. The difference in risk-tolerance between many kinds of people. People in white collar jobs, generally more coddled in life, are going to have a different response to risk than those who have very different lives.

3. A great many people don't agree w/ the local COVID policies, but have no power to change them until elections. This has actually happened in jurisdictions all over the US, but is largely not covered (VA elections had this as a bigger factor than was reported)

4. People, in the end, aren't as dumb as the experts want to proclaim. They can look around and see what's happened as part of their own, lived experience, and notice that the restrictions are entirely BS, have done basically nothing, COVID isn't nearly as dangerous as portrayed, and that the vaccines don't do virtually anything that was initially advertised. Being skeptical of utopian claims is actually a mark of wisdom, not something to be scorned (unless you're in the expert class trying to prove your worth to society).

Should these facts make us more skeptical of empirical research methods predicated on assumptions that two groups are basically similar? For example, the differences-in-differences technique requires an assumption of parallel trends--the trend of the control state post treatment maps out what would have happened in the treated state, in the absence of treatment. If neighbor regions that appear to be so similar on the surface can differ so wildly in response to covid, this seems to be a stronger assumption than previously thought. Of course, this assumption may be reasonably valid in non-outlier situations, but I see a lot of papers making assumptions like this to study Covid itself which seems inappropriate given your observations here.