Below is a lightly edited transcript of my conversation with Chris Nicholson on whether China can conquer Taiwan. The video is above.

To listen to the audio and find relevant links, click here. The audio, video, and transcript are all available to paid subscribers now and will be released for everyone else after one week.

Invasion or Blockade?

Richard: Hi everyone. Welcome to the podcast. I'm here with Chris Nicholson. Chris, as you know, loves all things war and all things military, and we're here to talk about, not Russia and Ukraine today, although that's a lot going on there, but the Taiwan and China situation. So Chris, we want to talk about some of the sort of military specifics of what a conflict here would potentially look like. And we're recording this just days after — we’re on October 17th, 2022 — the US imposed some restrictions to try to stop the development of China's chip industry. Maybe we'll get to that too. But for now, can you just pull up the... And this is going to be for people who are watching the video of this, and so people can follow along. But for the people listening on just audio, they're not going to be able to see what we're talking about. But just, can you pull up the map of what you're looking at?

Chris: Yeah, sure.

Richard: Okay. So that's Taiwan. It's right there in the southeast corner of the world. Okay. If you're China, what do you do? How do you take this island?

Chris: Okay, so there are a lot of factors to consider, and we definitely should talk about the semiconductor war that we've decided to start waging against them, because that's central to the military equation here. But, that'll come up a bit later. So Taiwan, right over here, a little over 100 miles away from mainland China. The basic two categories of military moves that we have to consider are an invasion versus a blockade. And most people have spent most of the time, over the last few years, talking about China invading Taiwan. And that is certainly an option. There are many considerations that arise, but a blockade is kind of the easier, slower military maneuver that they could employ against Taiwan.

And it's looking like a blockade is probably more likely. There's been more discussion lately about the US talking about whether it could break a Chinese blockade of Taiwan or not. So those are the two categories that we need to analyze.

Richard: And then you do the blockade and what? They surrender? Is that the point?

Chris: Yeah, so you do the blockade and the way you execute the blockade is basically you would surround Taiwan, especially its ports. You would use small, faster ships, you'd use a lot of submarines and you would basically control the imports and exports from Taiwan. So you would prevent semiconductors from leaving Taiwan, you'd interdict them, and maybe allow some of them through, maybe not. And China would potentially stop Taiwan from importing the oil that it needs or the food that it needs. Taiwan needs a lot of each. And so it would just apply the pressure and kind of strangle Taiwan until it gave in.

Richard: And then the other thing is an invasion. And how would you invade Taiwan?

Chris: The invasion would be much more difficult. This would be the largest amphibious assault that we've seen in history. It would dwarf D-Day. And these are some of the most complex, combined arms military operations that you can execute.

Richard: Why would it dwarf D-Day? What's so hard about this?

Chris: Well, it would just take a lot more men to take Taiwan through an invasion. It's hard to say exactly how many it would take, but it would take many trips back and forth. And China kind of has a limited amphibious assault capacity. This is related to one of the links that I pulled up. So let me just boil it down to the simplest parts. Okay. So you need boots on the ground in an invasion. And the way that China would have to get that is primarily, well, not primarily, but China would rely on its amphibious assault ships. China's been building a lot of those lately.

So these are military ships that carry troops and equipment like tanks. And China has built a limited number of these things, which is kind of interesting. Its military transports right now, it doesn't actually have that many. And their capacity is to land maybe 10,000 troops at a time on Taiwanese shores, 10,000 troops and equipment. That's a number that we might call a division, roughly. And 10,000 isn't that many, and they'd be under fire, under heavy fire from anti-ship missiles from Taiwan the entire time. It would be hell trying to make it across the strait. And then they'd have to claim the beaches.

Richard: Where can you actually land? I've heard that it's hard to... There's actually not that many places where you actually can land. Is this a major consideration here?

Chris: It is a major consideration. There are well-known, a certain number of limited, well-known landing sites that are prime opportunities for beachheads. And Taiwan is well aware of that. And they all tend to be mostly on the west coast of Taiwan. And that's really where it's most heavily populated, too. That's where all the ports tend to be. As you can see from the map right here, there's not that much on the east. It's mountainous and forested. So it's well-known and those areas are very well-defended. So this would really be hell to try to accomplish. Now, it could be done, potentially—

Richard: But how open is that west coast? Not even the whole west coast is open, right? Is each one of these ports just a little opening and the rest is mountains or what’s the geography?

Chris: Yeah, I'm not completely sure about that. And I forget the exact number of sites, but off the top of my head, the number of potential landing sites here, are on the west coast and in the southwest region. It's somewhere around a dozen, maybe a bit more than a dozen. So these are well-known and heavily defended. And there's a lot of discussion over whether China is capable of pulling off an invasion right now or anytime soon.

I will say that one major factor that most analysts don't consider is that they don't think about the possibility that China could employ its civilian transports to carry troops and equipment. This is a very important factor that really escapes a lot of US analysts. China’s military/civil structure is much more integrated than the United States’. For us, there's a very sharp division between what’s military and what’s civilian. For China, as part of their system of government, there's a much stronger integration. And so China has all these separate fleets that are semi-military that we tend to ignore in our analysis because they're just not under the label “navy.” They're not under the label “PLAN,” People's Liberation Army Navy.

One fleet we have to consider is its Coast Guard. It's got the world's largest coast guard. One thing China does is it takes military ships, capital ships, corvettes, small fast warships, and it just strips the missile tubes out and it sends them over to its Coast Guard and says, “Okay, you’re no longer a naval ship, you’re in the Coast Guard now.” And it's got 20 or 30 of those. If a war came, it could just strap missiles back onto those and suddenly, boom, more warships. We tend to ignore that.

The other really important fleet toward an invasion that we tend to ignore is what's called China’s Maritime Militia. And these are civilian ships, often fishing ships, and they are constructed according to military specifications. It’s been this way, at least for the last decade, I think. And so they’ve really been heavily involved in military exercises recently. China’s not being particularly secretive about this. It has its civilian transports do naval exercises with all the warships, and it loads them up with soldiers and tanks. So this is actually where the bulk of China's invasion capacity would come from.

Richard: And so are these ships, they're for state owned enterprises? What are they used for, usually?

Chris: In the Maritime Militia, some of them are used officially for fishing exercises. It's not clear how much fishing these fishing ships actually—

Richard: What's a fishing exercise?

Chris: Okay. I mean, just fishing. Officially, they're just used for fishing. Unofficially, the Maritime Militia, it’s employed in the South China Sea a lot. When you read in the news about China bullying the Philippines for instance, or Vietnam, really what that typically amounts to, is it’s sent its Maritime Militia fishing ships to just anchor down in a certain spot, a certain reef or something, and kind of crowd out the other countries that are around the South China Sea. It’s called a form of gray zone warfare, which China is really mastering that and using its semi-civilian fleets to accomplish that.

Now, the ships that I was just talking about, the ones that it would use to transport troops and equipment, those are often called ferries, especially what's called roll-on, roll-off ferries. Sometimes people abbreviate that as ro-ros. And so those, as the name says, officially, they're used to just ferry people and cars around. That’s what they’re supposedly intended for, to move lots of cars. But as a matter of fact, this would form the bulk of China’s amphibious assault capacity. And they have a quite large capacity here. I was just reading an article about it, good article from War on the Rocks, “The Cross-Strait Potential of China's Civilian Shipping Has Grown.” So to give you the bottom line here, and here you see one of these ferries that it could use.

Richard: Yeah, when I think of ferry, I think of those little things that you bicycle across the sea, but that’s not what that is.

Chris: And these things are actually, in some ways, better for this purpose than dedicated military amphibious assault ships, although China has a few of those now. Because the military versions, they’re kind of optimized to extend farther out, to be able to sustain a few hundred marines at sea for weeks or even months. But here, when it comes to invading Taiwan, China just needs to take as many soldiers and their equipment across the 100-mile strait. And so there’s no frills. They’re just optimized to carry as much as possible. And in reading this, the bottom line to it was something like this. If you just look at the dedicated military amphibious assault ships, China can carry maybe 10,000 soldiers at a time. If you include all of their civilian transports, that number rockets up to somewhere around 300,000.

And so this is a major factor in China’s invasion capacity that American analysts often ignore. And it’s really dumb how they ignore it. You read some articles from American analysts saying, “Oh, we don't need to worry about a Chinese invasion of Taiwan because they would need a lot of transport capacity. We add up their military transports and we say, oh, they can only transport 10,000. They're nowhere close to the capability they need.” And then as an observer, you have to sit back and think like, “Wow, that's really dumb of China to not build transports when it wants to invade Taiwan.” But the answer is, it has. It just labels them “civilian.”

Richard: So how many are in the Coast Guard? And how many are just... I mean, I assume they’re state-owned enterprises, they’re something the government can call on, basically anytime they want? Are they around the world fishing and they’d have to be called back and repurposed? I mean, how available is this stuff?

Chris: That’s a good question. So China’s Maritime Militia, it does kind of roam. Now, these particular ones, the transports, the ferries—

Richard: The Maritime Militia, what is it? Is it a branch of the military? What is it?

Chris: Officially, yes. I think its status is a bit of a legal gray area, and this is constantly in flux. Just a year or two ago, China passed a law that more closely integrated its Coast Guard and its military. And I think around the same time, China passed a law authorizing its Coast Guard to fire upon enemy ships when they intruded into—

Richard: So, this is the Coast Guard?

Chris: That’s the Coast Guard. Now, the Maritime Militia, in the Maritime Militia, we ought to separate the fishing ships from the ferries. The ferries, I think those tend to be close to Chinese shores. And there are some Hong Kong ferries, too. That’s an important branch. They tend to—

Richard: Why do they have fishing boats, ostensibly, within this branch of the military? Why does the military... It just catches fish for—

Chris: Well, it’s a gray zone strategy. Remember, this is a kind of hybrid warfare that Russia really started to pioneer back in 2014 when it used these gray zone tactics. People called them little green men.

Richard: So they built the fishing boats. They’re not actually... I mean, are they fishing? Do they sell fish?

Chris: Officially, they are intended and designed to fish.

Richard: But why would you do that? Why would your military have fishing? But, does the military do that? Militaries don’t do that, right?

Chris: Well, China does. It’s kind of pioneering this and it’s because this is the idea of gray zone warfare. You want to use a level of force that’s semi-military, that’s enough to bully around Filipino fishermen, but that is not a high enough level of military force to invite a naval response, from the United States especially. So that’s where the Coast Guard comes in. It’s a level of military force that the Coast Guard ships have big guns, they’ve got helicopters, they have machine guns, but they don’t have missile tubes. So the Coast Guard is the level of force just below a navy. And the Maritime Militia is a level of force just below the Coast Guard where these fishing ships, they might have some guns, they are built to be able to ram other ships, for instance. They’re designed to be able to ram effectively. And they have water guns, sometimes.

Richard: Water guns, as in they squirt water?

Chris: Yeah. They shoot water with great force. And so they go up to the Filipino fishermen and they don’t pump them full with lead. They just shoot these forceful water guns at them and that’s enough to drive them off. And so that’s critical to gray zone military tactics, to employ a level of force just above the opposing fishermen. Enough to bully them, but not enough to invite a US naval response.

Richard: Is this something the US or the Western countries do, equivalent to this, these so-called gray zone tactics? So when the US arrested the high ranking official from Huawei, they had the Canadians arrest her, I think she just stayed under house arrest in Canada, and then went home. I guess this is maybe something else. Is the gray zone defined as something that’s like military, but not quite military, but it’s connected to the government? Is that sort of the definition?

Chris: Basically. And it’s called gray zone because it occupies a legal gray area.

Richard: So what about Blackwater? Would that be something like the US, if they would have to be used strategically? If they’re just used in, sort of everything’s out in the open, then it’s not? But if they were, I don’t know, out overthrowing other countries, that would be sort of a kind of gray zone?

Chris: We don’t really talk about gray zone tactics much when it comes to the United States. And in part, it’s because we don’t really do that much of that. China is the one really pioneering this area. We have to think about trying to catch up to them. There’s some talk of sending some US Coast Guard ships over to the area to respond to China’s own coast guard. We don’t want to escalate by responding to their coast guard or militia with destroyers, with warships. So we kind of are catching up to these tactics still.

We don’t employ many gray zone tactics ourselves, especially navally. Now you could try to call something like Blackwater... I think it’s been renamed, by the way. I forget what its new name is, but they don’t want the Blackwater brand anymore. You could try to call that a version of gray zone tactics. It normally isn’t, but yeah, it’s in the same spirit. If we tried to hire Blackwater, whatever it’s named now, to do something instead of our own military—

Richard: Wagner and Russia would be something like this, right? Even though they’re more integrated into the Ukraine war, when they go out and they just do stuff in other areas, that’s like gray zone?

Chris: Yep. Kind of.

Richard: Okay. China has potentially the equipment to transfer a lot of these... Okay, so this makes sense, because I would read these Chinese fishing vessels are pushing around Filipinos or Vietnamese. And you know, fishing vessel, like what’s that? Okay. So they’re military fishing vessels, that supposedly are supposed to just catch fish, but are actually just used to bully. How old are these fishing vessels? How long have they been doing this?

Chris: Not that old. Some of them are probably older, but I think a lot of them have been built and employed within the last decade or so.

Richard: Okay. I mean, is there an ancient Chinese tradition of having fishing boats as part of your military or something? Or does it seem like a more conscious strategy to just invent something new?

Chris: I don’t know if there’s an ancient Chinese tradition of it, but these particular gray zone tactics, these are something that we’ve really seen China use a lot of within the last decade, I would say.

Defending Against an Invasion

Richard: Okay, so you have the capabilities to invade. It’s tough because the Taiwanese know where sites are. What about air power? What can China do? We’ve been watching this in the Russia war. I mean, I’m surprised how little Russia can do with infrastructure. I thought having missiles and stuff, you can knock out a country’s power, but apparently that’s not the easiest thing in the world to do. What can China do, sort of, from the air to Taiwan?

Chris: Well, they can do a lot. China’s been developing its air force, its bombers, its fighters, its aircraft carriers. And so certainly it could contribute a lot of firepower from the air. Now, I want to be careful. I don’t want to say that China could invade Taiwan tomorrow. I do want to say that in any consideration of its capacity, it’s a central consideration that you consider its civilian transports from its Maritime Militia, especially the roll-on, roll-off ferries. That is the central capacity it would use to carry troops. At the same time, the fact remains that it is very difficult to conduct an invasion, an amphibious assault on that scale. And a lot of these would be sunk and they’re juicy targets, these civilian ferries. There are various things that China would do to try and protect them. It’s got all its ships, its destroyers, its frigates.

We’ll probably talk about a bit more as this goes on, about different classifications of ships and their role. And those are outfitted with missiles that it would use to try to shoot down the Taiwanese missiles to protect the ferries, to protect the transports. Another thing it would do, I read an interesting think tank analysis that was specifically on the subject of all the different ways that China could use its Maritime Militia to supplement an invasion. And they can make contributions beyond just the transport capacity itself. I was reading in this analysis, it was saying that it could basically use some of its civilian ships as decoys, outfit them with radars and mirrors and other measures to blind the Taiwanese sensors to try to disguise the ferries.

So there are many considerations on both sides here. At the end of the day, I’m left thinking that China is not quite ready to pull off an invasion of Taiwan. It would be pretty bloody. And it’s far from a sure thing. And so I think that when it comes to invasion, China probably wants to build up its capacity for at least a few more years.

Richard: Yeah, I mean there’s—

Chris: That’s why a blockade is a much easier affair.

Richard: Yeah, it’s interesting because China has one real foreign policy goal, which is to reunite with Taiwan. And everything else seems secondary, as far as what it can do with its military. And Taiwan has one military goal, which is to defend itself against a Chinese invasion. And I mean, it’s interesting. It’s just the specifics of whether the offense or defense is favored here. And this looks like a situation where it’s clearly the defense that’s favored. But China is a much bigger country, has a lot more resources to throw at this thing. But yeah, I mean we saw in Russia-Ukraine and the various US wars where it lost against weaker opponents, that’s not the end-all, be-all. So it’s very hard, right?

Chris: Yeah. So I’ll tell you, when it comes down to an invasion scenario, basically the key element is how quickly could Taiwan and say, the United States, shoot down all the Chinese transports, both military and civilian. And this is something that came up in some prominent recent war games that were publicized. There were a bunch of articles about the results of these war games. And the war games, they were kind of phrased as if the United States and Taiwan fended off the Chinese after three weeks or so. Because what they said was, after three weeks we shot down all of the Chinese military transports and so then what they were left with were 10 or 20,000 soldiers stranded on the west coast of Taiwan without the possibility of reinforcement. Now, these war games, I don’t think they fully considered all of the civilian transport that China could use. At the same time, that is the consideration that it would come down to. Our submarines, especially, would also be having a field day trying to sink China’s transports in the strait.

Richard: But China is right there off its own coast. So Taiwan and the US would have... But China would also have these air bases right on the coast and I guess so would Taiwan. But I mean presumably China would have a lot more, right? So that would factor into the battle.

Chris: It would. But we have certain advantages. And one of our biggest military advantages against China, both in an invasion and blockade scenario, is our submarine fleet. Our submarine fleet is pretty unmatched. And all of our subs are nuclear. They’re very stealthy, very quiet, and very modern. And so a lot of this comes down to how good China could become at anti-submarine warfare.

Richard: Well, I mean, this is a big assumption. The US goes directly and starts shooting at Chinese ships. I don’t think that that’s anywhere close to guaranteed, right?

Chris: Well, that’s kind of the big question. And what we have to do to figure that out is consider how it would go. I’m not really making the assumption. It’s that both sides are making the assumption that the US would intervene, in order to figure out whether the US could or should intervene.

Why a Blockade Can Work

Richard: And even if it goes well, you also have a whole set of new problems, too. So yeah, it doesn’t answer the question that obviously. But okay, so that’s the invasion scenario. Now, how does the blockade look like? So you just have this west coast. This west coast is where the ports are, and that seems manageable, just looking at the map.

Chris: Yeah, this is actually what we saw China practice a version of in its extensive naval exercises, right after Pelosi’s visit. Well, during Pelosi’s visit too, I think. China really did a bunch of war games where it didn’t game out a complete blockade of Taiwan, but it chose many zones of Taiwan. I think there were six zones or so that it exercised in. What was kind of interesting about those exercises is that although they were officially kind of simulating a partial blockade, they weren’t actually using the same ships that they would use in a real blockade.

So you have to separate capital ships, warships. The big warships are called capital ships, and those can be divided into the bigger ones and the smaller ones. So the bigger ones are cruisers and destroyers. What’s interesting is that in those exercises around the time of Pelosi’s visit, China simulated a partial blockade using its big capital ships, its cruisers and destroyers. And those are not, in fact, the main capital ships that it would employ in an actual blockade. For those, it would use the smaller ones, the frigates and the corvettes, because those are smaller and faster. And so those are better at intercepting ships.

Richard: So to stop merchant vessels from getting in, you don’t need the big destroyers, right?

Chris: Exactly.

Richard: You just need something.

Chris: Exactly. You don’t need a hammer to squash a nail. You need to get the smaller, faster ships. And not only that, there’s the consideration about what you want to expose to Taiwanese firepower, what you want to risk losing to Taiwanese anti-ship missiles. There’s no reason to send your biggest, most expensive ships for the purpose of a simple blockade. Those ships are intended to fight other big ships. For this purpose, you want to use the small, cheap ships that you wouldn’t mind losing, that are fast enough to intercept merchant ships.

Richard: Yeah, even if—

Chris: And you’d use submarines.

Richard: And even if China—

Chris: And the Coast Guard too.

Richard: Yeah.

Chris: The Coast Guard is relevant, I think, in the blockade scenario. China’s Coast Guard is massive. It’s got at least a couple hundred ships. Many of those are former naval ships, so its Coast Guard would be especially relevant to enforcing a blockade of Taiwan. That’s a large capability that the United States often doesn’t consider for whatever reason.

Richard: How easy is it to make sure nothing gets through? I’m thinking it’s very easy because merchants, they’re going to be risk averse. They’re not military.

Chris: Exactly.

Richard: If there’s a chance they might get shot or captured, they’re not going to go there. It’s not going to be worth it, right?

Chris: Exactly. I think that’s the main consideration. It’s not really so much about whether they could make an impenetrable net around Taiwan. Even if it’s semipermeable, but there’s great risk to a ship, it no longer makes business sense to try.

Richard: Even if Taiwan fights, it’s a war zone. It’s still a big risk. You have to get rid of them on the coast completely for this stuff to stop this, right?

Chris: Sorry, what are you getting at there?

Richard: Even if Taiwan... It’s like Taiwan has these battles at sea where it goes out and tries to fight the Chinese ships, that’s still the blockade. As long as the battle’s going on, there’s going to be a blockade because merchants aren’t going to go through that, right?

Chris: Yeah. Now, there’s a lot of discussion about how effectively the United States could puncture a Chinese blockade. There were some articles that came out a week or two ago where a US Admiral was saying, “We could definitely puncture a Chinese blockade.” So the key to this battle would be our submarines versus their anti-submarine warfare. This is a capability that right now is our biggest naval advantage. China is working on developing its anti-submarine warfare capacity in various ways. It’s building its own submarines. It’s building a lot more helicopters and planes that specialize in finding and destroying submarines. But it’s not clear that China is all the way there yet. It might want at least another year or two to build up these capacities and the training to execute them.

Richard: Right. There’s no way to, I guess, keep Taiwan fed from the east. The ports aren’t there. I guess the road system’s probably not that great. Maybe you could fly in, like West Berlin, you could fly in some essentials, right? Not oil.

Chris: I think that would be pretty shaky. The volume would be so low. It would be so expensive, so difficult. Then the planes themselves would be so vulnerable. I don’t really think that flying in supplies is a viable option.

Taiwan’s Plan is to Wait for the US

Richard: Okay. If the US is... Let’s try the assumption that the US doesn’t want to directly fight China, and I think that’s probably the most likely scenario. What can Taiwan do? Is there a way without the US submarines coming to their rescue, is there any way they could break this thing?

Chris: On their own, no. Taiwan’s entire military strategy is basically built on holding out, defending itself for a few days to a few weeks until the US cavalry can arrive. That’s basically their entire plan.

Richard: But that seems like a strange plan given that the US doesn’t have an official guarantee to fight for Taiwan. It doesn’t even recognize Taiwanese independence. It seems to me they’re putting a lot of eggs in that basket, isn’t it?

Chris: Yeah. But what else can they do? They’re an island of 20 million people. There’s 1.5 billion Chinese people out there, and they’re right next to them. There’s only so much Taiwan can do.

Richard: They could spend more of their GDP on... They don’t spend that much militarily.

Chris: They can, and they probably should. I think Taiwan has been fairly lax in investing in its own defense over the last several years, the last decade. In fact, the US is kind of pissed at Taiwan right now over not taking its own defense seriously enough. Taiwan has tended to invest in these big flashy military capabilities. For instance, Taiwan just commissioned its first amphibious transport ship. That’s an odd thing for Taiwan to invest in. What it ought to be interested in is defending its own island. It ought to be buying a lot of small things like missiles. It ought to be buying anti-ship missiles by the bushel. But instead, it spent a lot of money on this amphibious transport ship, like it wants to go on the offensive in a war against China. I’m looking at Taiwan thinking, “You think that you need to invest in the capability to invade islands that China’s holding and assault them?” That’s not really a wise use of their money.

Richard: Is it that crazy? I think before the Ukraine war started, people would’ve thought, “There’s no way Ukraine could ever go on the offense.” Then just a day or two ago, there were strikes in Belgorod, and that seems to be happening a lot. Could they, I don’t know, have missiles? I don’t know about an invasion, but could they do something that could potentially raise the cost of China doing a blockade or an invasion?

Chris: Certainly. Certainly what Taiwan ought to be doing is foregoing all the advanced splashy capabilities, the amphibious transport docks, the jets, the expensive fighters, the ships of all kinds, tanks. What Taiwan really should be investing in is as many anti-ship missiles as it can get its hands on. It should also be getting HIMARS and all the rockets to be launched from it. They should be getting all of that smaller stuff. This is related to what has lately come to be known as the porcupine strategy. Have you heard that term?

Richard: I’ve heard it.

Chris: Yeah, it’s the term that some military guys have started throwing around lately. Basically, we want to make Taiwan into a giant porcupine bristling with anti-ship missiles. That’s what it should be doing.

Richard: Yeah. Is there support within Taiwan for... Is there some support for being reunited with China? I’ve seen polls that indicate maybe. I’ve seen a little bit of this. It seems like the trend is in the direction towards more being separate from China.

Chris: Yeah.

Richard: This was an open question before the Russia invasion of Ukraine. I think a lot of people thought Russia had more support within Ukraine than it actually did, although it always had some support. Has China infiltrated Taiwan well? Does it have sleeper agents? Does it have sympathizers? Could it rely on Taiwan not holding together in an invasion or a blockade?

Chris: I would be shocked if China had not infiltrated Taiwan to some degree. How great is that degree? I don’t get the impression that there is especially strong Taiwanese support to be reunified with China. As you said, I think the trends currently are more toward independence of one kind or another, official or unofficial.

Richard: It’s hard. It’s such a different situation. Russia was vulnerable when it invaded because it didn’t have enough men and was covering all this land. It could be hit by these small roving bands. Very mobile, small groups could attack Russia. On the ocean, you can’t rely on the populace to go out there and fight a sea battle. It’s more a conventional military thing. In which case, maybe it’s more difficult, maybe that public support really doesn’t matter all that much. It’s just classic military capabilities.

Could There Be an Insurgency in Taiwan?

Chris: Right. But that’s stage one. If the amphibious assault goes well, there’s going to be lots of Chinese boots on the ground. At that point, the Taiwanese populace is a key element, their ability to fight and their willingness

Richard: Maybe. In the Ukraine situation, it was the fact that there had been some resistance within the occupied territories, but it’s in the context of a larger war going on. There’s still a Ukrainian government. If China took... We don’t know if there would’ve been a Ukrainian... How much of a Ukrainian resistance there would’ve been without a Ukrainian government. There was a Ukrainian government. It seems like there’s not a strict line between the government and the insurgency.

The insurgency on parts of Ukraine, it’s not like it’s huge. These cities that Russia takes, there’s assassinations and such, but it’s not like when the US was occupying Baghdad, where the US couldn’t drive down the street without getting blown up or shot, so maybe not. Maybe it’s not that hard to just hold out, especially if they have enough troops. Russia had a relatively small number of troops, especially if China brought whatever, I don’t know what counterinsurgency theorists recommend, but whatever Russia had in Ukraine, it wasn’t nearly enough. They had 150,000. They needed 500,000, a million, or whatever the formula is. Maybe China sends out enough men and maybe they don’t have to deal with that much of a resistance.

Chris: It’s an open question right now how many Taiwanese people would be willing to take up arms against a Chinese invasion and how effective they would be. I don’t think anybody can have a high degree of confidence about those questions right now. We see signs of the Taiwanese becoming more willing to fight. I think Ukraine has played a role in inspiring some of them to think that it’s possible to effectively resist.

Richard: I think that’s right. I think the mental, the spectacle of what’s going on in Ukraine, I think China would... Both sides learn from it. China’s not going to make the same mistake as Russia. They’re not going to send in 100,000 troops, expect to be greeted as liberators, and not even call it a war. They’re not going to do that strategy. Maybe they would’ve been stupid enough to do something like that before. Taiwan maybe is going to see resistance as something that realistically they can do once they’ve been conquered, right?

Chinese Missiles Can Destroy US Ships and Military Bases

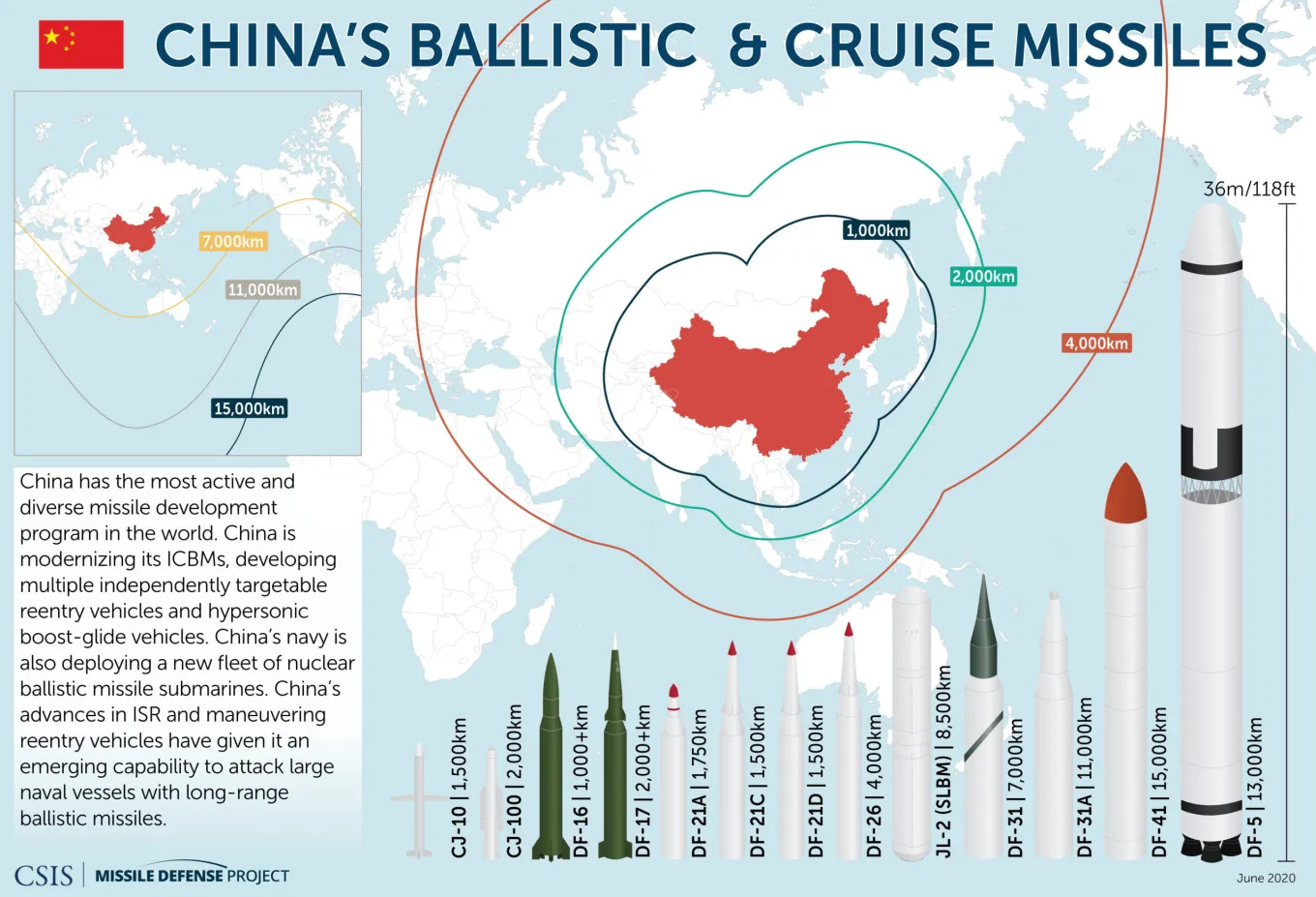

Chris: Yeah. China has a key military capability that’s relevant to all of this that I haven’t mentioned so far. Might as well bring it up sooner than later. Taiwan is really going to have to rely on its civilians for resistance and for whatever military capabilities are highly mobile and easy to disguise because any bases, any kind of fixed hard points that are storing equipment and weapons, are probably going to be taken out relatively quickly because one of the main military capabilities that China’s been investing in is its intermediate-range ballistic missiles. This is related to what we call China’s Anti-Access Area Denial strategy, AA/AD. This is the reason why our own navy is not an enormous factor in this, not as much as you might expect, because China has designed massive quantities of these intermediate-range ballistic missiles that can take out a variety of these targets.

Certainly in the early days of the war, it would use its missiles to wipe out as many Taiwanese air defenses as possible, as many of their anti-ship defenses as possible. Really, Taiwan would have to rely on whatever’s mobile. That’s what it really needs to invest in, mobile anti-ship capabilities. This massive Chinese rocket ballistic missile arsenal is also a key reason why the US naval response, I’ve really been focusing on the submarines so far, because our submarine fleet is vast, highly advanced, and it’s what we have that can get there. The US Navy is built on the backbone of our carriers. Our aircraft carriers, especially our 11 or so supercarriers, are what have traditionally made us seem invincible to other people. The United States has 11 supercarriers, and those can carry anywhere from 70 to 90 fighters at a time.

The next highest nation with the number of carriers, China has three right now. It just launched a third. The UK has two. I think India has two. We have a lot more than anybody else. We also have nine light carriers. We call them amphibious assault ships. But ours are capable of carrying helicopters and fighters. The F-35B is a modern fifth-generation fighter that is capable of taking off short and vertically from an amphibious assault ship. We have a ton of carriers. But the thing is that China has invested for a long time in these intermediate-range ballistic missiles that have a range of, say 4,000 kilometers or so. Remember, everybody other than us thinks in terms of kilometers. That’s what the analysis comes in. These things, we don’t have these ourselves, by the way, because until recently, we were forbidden by treaty from developing our own intermediate-range ballistic missiles. Us and Russia were bound to that treaty until...

Richard: This was so Russia and Europe couldn’t fire missiles, Russia to Europe and vice versa.

Chris: Yeah. But China had no such obligation. It’s been building up an arsenal of these things. The main ones to keep an eye on are, I think, the DF-21. That’s its shorter range one, with a range of maybe 2,000 kilometers. Then for our purposes, especially relevant is the DF-26. There’s an anti-ship version of it called, I think, the DF-26D. Those things have a range of somewhere around 4,000 kilometers. This tiny spec on the map here, let me zoom in and see if this is Guam. No, that’s not Guam. Let me look for Guam. Guam is too small to show up on the map unless you look for it. Guam is the United States’ key naval base in this region.

Richard: How many kilometers is that from China?

Chris: Sorry, what was that?

Richard: How many kilometers is that from China?

Chris: It turns out to be basically the range of China’s DF-26 ballistic missile.

Richard: They could fire it from the sea too, couldn’t they?

Chris: No, these particular ballistic missiles are fired from land.

Richard: Okay.

Chris: Let’s measure this roughly. Okay, so this is 3,000 kilometers. So Guam is well within range of these Chinese missiles. And the gist of it, China labels these things “carrier killers” for a reason. If it comes to blows, we have kind of accepted that we cannot station our carrier strike groups within range of these missiles. We can’t do that and expect them to survive. In the recent war games that were publicized pretty widely, we were expecting to lose two carrier strike groups within the first few weeks of a war. And if we lose even one of these things, that’s viewed as a disaster for us.

Richard: What this means is that the US cannot send fighters or bombers basically, right?

Chris: Bombers are a different matter. Now, fighters we can’t send.

Richard: Go ahead.

Chris: Fighters have a short range. For our fighters to really be within range, they’d have to be carried by our aircraft carriers. And our carriers can’t really get within range.

Richard: But these aircraft carriers and the base at Guam, they must have good air defenses, right?

Chris: Well, air defenses can only be so good, especially against ballistic missiles. You should separate missiles into cruise missiles and ballistic missiles. I think cruise missiles are easier to shoot down. They fly lower and slower. Ballistic missiles come in from high and fast. I have a friend who’s a rocket scientist, he works on Starlink right now. It’s kind of sad, my friend’s skills are ideally suited to working on military projects, but he doesn’t want to work on military stuff. But his career, he moves from place to place trying to avoid working on military stuff, and he can’t avoid it. Now he’s working on Starlink.

Richard: Starlink ends up a military weapon.

Chris: That turns out to be a crucial military capacity. So my rocket scientist friend explained it to me once — he works on rockets that are related to all these missile capabilities — and he doesn’t really think that it can be that effective. He doesn’t have great faith in the ability of missiles to shoot down other missiles. He told me, “Imagine that you’re trying to shoot a bullet out of the air with another bullet.” Very difficult. You can have some success, sure. But you really need a lot of volume. The offense has the advantage.

We’ve been talking in our last podcast about Ukraine. We were talking about where the offense has the advantage and where the defense has the advantage. Now, in many aspects in the Ukraine ground war, the defense is at an advantage. When we come to the issue of ballistic missiles and defense against ballistic missiles, trying to shoot them down, in this important aspect of naval warfare, it’s really the offense that has the advantage. It’s a lot easier to overwhelm a strike group of ships with ballistic missiles than it is for that group to effectively shoot those missiles down.

Richard: Yeah. So what Russia was firing at Ukraine recently, a week or two ago, there were 80 missiles, and 40 of them were shot down or something. Those were all cruise missiles. They were not ballistic missiles.

Chris: I think the majority of those were probably cruise missiles.

Richard: Okay, so Ukraine can get 50% of those. Russia just doesn’t have enough ballistic missiles. They would’ve fired ballistic missiles, which are just better if they could have, right?

Chris: Yeah. They’re better. They’re rarer. By the way, the news just came out, I think, yesterday that Iran is probably selling a bunch of these cruise missiles and its ballistic missiles to Russia. So that’s a relevant factor.

Richard: How many IRBMs does China have?

Chris: It’s hard to say. This is something that obviously it’s keeping pretty close to the vest. But it’s numbered in at least the several hundreds, if not the thousands.

Richard: You don’t need a lot of them to get through to destroy a military base. You just need a few.

Chris: As a sign of how worried we are about these, I think just a few years ago, the news came out. Up until recently, our air force stationed a lot of bombers on Guam. And then a few years ago, the news came out, “We’re no longer going to station bombers on Guam. It’s fine. We can put them somewhere else.” Well, that was because we knew that Guam would be overwhelmed with these intermediate-range ballistic missiles in the early stages of any war. We are worried enough about these that we’ve decided we can no longer station bombers on Guam.

Richard: Yeah. Okay, so the US situation is if it wants to help, its aircraft carriers are useless. The fighters are not going to be very useful. They have submarines, which are potentially helpful. Then what about regular cruisers, destroyers, ships like that? Those can be part of it if they wanted, right?

Chris: Well, those are also vulnerable to the massive Chinese rocket arsenal.

Richard: Aren’t they mobile? Aren’t they harder to hit than...

Chris: Yeah, they’re mobile. Look, certainly, there are many considerations here. I don’t want to exaggerate it and say that any US strike group is an automatic goner. There are factors you have to consider. The technical military term for this is called the “kill chain.” There is a chain of events that has to happen in order for these ships to end up getting killed by the Chinese. The various steps, I’m probably not going to get every step accurately, but the important thing is that first, the Chinese have to be able to spot where our ships are. They’d use satellites. They’d use various underwater sensors that would try to detect them. They’d use radar and other capabilities. So, first step is they’ve got to find our ships. And we have various methods we would use to try to prevent them from finding our ships. This links into the whole issue of Trump creating the Space Force.

I think some people laughed at the idea of a Space Force. No, the Space Force is important because satellites play a central role in identifying these ships. And so our defenses, before you even get to the level of anti-ballistic missile defense, where our cruisers and destroyers would try to shoot down the Chinese missiles, our best hope really would be trying to prevent the Chinese from really effectively identifying our ships. We can’t just assume that the Chinese would know where our ships are. There is a game to be played there that we could play with some effectiveness.

Richard: Let me ask you this question. If the US doesn’t want to get directly involved with China, but it wants Taiwan to defend itself, why doesn’t it just give Taiwan half of its submarines? Why doesn’t it just give them all their submarines and let them do it?

Chris: That’s an interesting question. So first of all, there’s the issue of training. It just takes a long time to train the sailors to man all of these things. Second, there’s the question of escalation. If we did just hand over all these advanced submarines—I mean, nuclear attack submarines, that’s some of the most advanced military technology in the world. We just inked a deal called AUKUS between the United States, the UK, and Australia for the US to give Australia nuclear attack submarines. China was not at all happy about this deal.

Richard: Nuclear attack, are they nuclear powered or they’re for nuclear use?

Chris: Ah. So we have to distinguish attack submarines from ballistic missile submarines. The super-secret, quiet subs that you put the nuclear missiles on to annihilate another nation in what might be called a potentially second-strike capability—these are not the main ones that we have to consider in all of this. Those subs are just off on their own, chilling out deep in the ocean to annihilate any nation that tries to nuke us. That’s the role that the ballistic nuclear submarines play. They are a crucial element that gives us what we call second-strike capability. If somebody nukes us first… they don’t nuke us first because they know even if they annihilate us, our subs are out there to get revenge in a second strike.

That is separate from the main consideration here, which are the attack submarines. Those are the bulk of our submarine force. We’ve got 60 or so of those, something like that. Those are nuclear powered, but they don’t have nuclear weapons on them. It’s just the nuclear power is an important capability because it allows them to stay at sea without replenishment for longer. That’s one of the key reasons why the nuclear element is important to those.

Richard: Yeah. It’s confusing to call it nuclear attack submarine. You can see why.

Chris: Yeah. They attack other ships. They’re meant to attack other ships, not other countries.

Richard: It sounds like with nuclear weapons, whatever they’re using to attack, it sounds like they’re... Okay, got it. It’s escalation, but I wonder if it’s... It’s escalation. You worry about escalation from the American perspective because you’re worried about you having to be involved in the war, right? If you give Taiwan the submarines, maybe the war becomes more likely. But they could fight it better, and you don’t have to be involved. I guess the timing of this is difficult because from the time you start doing this to the time that they actually get the submarines and figure out how to use them, there’s some delay there. But also, maybe Taiwan does not want this. For them, the best-case scenario is not provoking China, and then having the US come to their aid. They don’t want to reduce the odds of the US coming to their aid. That’s the worst of all worlds.

Chris: I don’t think it’s really a realistic option for us to just hand Taiwan a bunch of nuclear attack submarines. First of all, it’s just so much easier said than done. They wouldn’t know how to use them if we gave them.

Richard: They’re smart. They’re Chinese. They could figure it out.

Chris: It’s not like it would tip the military balance— 10, 20 nuclear attack subs. That wouldn’t tip it. We’d be better able to use them than Taiwan would. We would be able to use them in conjunction with, say our bombers. Our bombers would be another key capability. They’d have a very long range so they would be able to contribute to any fight. It’s really just needlessly dividing our strength if we even attempted something like that. It wouldn’t move the needle. It would make us weaker overall.

Richard: Assuming that the US wants to get involved, which we don’t know.

Chris: There is not a hope that Taiwan could hold out on its own without the US. If the US is not fighting, there’s no discussion. Taiwan’s losing.

Richard: There’s no point in giving them nuclear attack submarines. I see. The South China Sea, the artificial islands that they’re building, is this relevant to the Taiwan thing or is it just about pushing around those other countries down there?

Chris: I think this is mostly a separate situation. This is a separate territorial interest that China is pursuing. These artificial islands it’s constructed, it’s loaded them up with missiles, with some other military...

Richard: Is it both the Paracel Islands and the Spratly Islands?

Chris: Well, so these are different matter from the artificial islands, the artificial reefs.

Richard: Where are the artificial islands? They’re close around there, right?

Chris: They’re kind of scattered throughout the region.

Richard: They’re not on the map, I presume?

Chris: Now, they do have potentially some relevance. There is an issue we haven’t discussed yet that is relevant to the military angle here. So there are a couple important things we haven’t discussed yet. So let me just get to them in order, as kind of a preview. As kind of a preview.

Richard: Now Chris is going through the map, for people who are not watching the video. But yeah, go ahead.

The Rise of the Chinese Navy

Chris: So we haven’t talked yet about the relevance of the Indian Ocean region to any of these conflicts. And we will get to that. Because it turns out what I’ve been saying is that the United States can’t really effectively beat China in a naval battle near its shores, the East China Sea and the South China Sea. Thanks to its anti-access area denial strategy, we can’t effectively get that close. And the closer we get the easier it’s going to be for it to spot our ships and wipe them out. We also haven’t talked about the relative ship capacities and the shipbuilding capacities. So let me turn to that next. But as a preview, it turns out that our greatest advantage is that we probably could beat China in a naval battle in the Indian Ocean region. And so that turns out to be our best response. If they invade or blockade Taiwan, we can cut them off with a counter-blockade, cutting off their oil supply lines to the Middle East. We could blockade them in reverse, basically. That’ll turn out to be our best response.

Richard: Does that matter? I mean you still have land, you have the rest of the world.

Chris: Yeah, let’s get to that later, because that’s more toward the end of the story about what options are available to us. But first, let’s fully flesh out the problems that we face. So, I’ve mentioned one major problem we face, which is China’s anti-access area denial. Its vast array of intermediate-range ballistic missiles. Our fleet is designed around aircraft carriers. And our aircraft carriers would have a lot of trouble getting into the fight. Our simulations say that we’re looking at losing two aircraft carriers and all of their escorts very quickly in any war. And yeah, maybe we have 11 of these, but when you compare the US Navy and the Chinese Navy, a lot of people make the mistake of just looking at the ship counts.

Richard: Mm-hmm.

Chris: And they don’t realize everything China has is in the area of the fight. The United States is a global, what’s called a blue water navy, and we’ve got all kinds of commitments with our ships, all around the globe.

At any one time, of our 11 carriers or so, a bunch of them are in for refit and repairs. And then you’re looking at seeing at least one in the Mediterranean area. Maybe you’re looking at having one somewhere around the Middle East, maybe in the Arabian Sea or somewhere near there. Maybe you’d have one up near the Baltic Sea, something like that. So our carriers are really split, our navy is split. So you can’t just add up the ships and say “who’s got more?” Everything China has, is in the area of the fight. Ours is all split up. Other thing that you’ve got to look at when it comes to these ship capacities, you’ve got to look at the raw numbers of ships.

Richard: Wait, you could just move them. They’re ships, you could just move them.

Chris: Well, yeah, but then we don’t have them in the areas where we need them to provide protection against say, Russia.

Richard: I mean, I think you can maybe neglect the threat from Iran, I mean during this war, the idea that Iran’s going to invade its neighbors. So maybe you don’t need the Middle East. I don’t know where else they would be.

Chris: So certainly we would have a degree of flexibility where we could just abandon, temporarily, some of our defense commitments that our navy has in other regions of the world. But to a certain extent, we’re using the carriers elsewhere and to a certain extent we want to use some of them elsewhere.

Richard: Yeah, okay.

Chris: Now, let’s talk about raw numbers. Much has been made lately of the fact that China is now the largest navy in the world by ship count. Now, what people will often say is that you can’t just look at the number of ships, you gotta look at their quality, you gotta look at how big they are too. The tonnage of the US Navy still at least doubles China’s, and that’s largely because of our carriers and our amphibious assault ships. But China has been rapidly building its navy over the last decade. It has really surged ahead. And every time you look at the situation, every time you check back in, it turns out that China has built new ships faster than we had anticipated. And it continues that trendline. I think the news just came out a few weeks ago, a picture of a Chinese shipyard came out, where it’s got a clutch of another six destroyers that it’s building in that one single shipyard.

Richard: Yeah.

Chris: Now let me quantify that for you. The United States, other than our carriers, the backbone of our navy is our destroyer fleet. We have, I think 70 or so.

Richard: Can you pull up a picture of a destroyer? I want to see what destroyers look like.

Chris: Okay. Let me look up, let me show you our main destroyers... Arleigh Burke destroyers. So these are our fighters. Our fighters in the sense that these are our main muscle.

Richard: But what do they shoot? Do they have cannons? Cannons. What do they shoot with? What’s their... just artillery?

Chris: Well, all... Okay. So really it comes down to missiles. I mean, every ship does have big guns, you can see the big gun right here.

Richard: Yeah.

Chris: But that’s not the main consideration. In these battles it really comes down to the missiles. The missiles that we shoot them with and the missiles that we defend against their missiles with.

Richard: And planes can take off from there, I assume, right?

Chris: Well, these destroyers, they don’t carry fighters. They do carry a couple helicopters. And helicopters are an important element of all this, an important capability, because helicopters add a lot of flexibility to the capability of the destroyer. Helicopters turn out to be one of the keys to anti-submarine warfare. Basically, in the grand chain of being, navally, submarines rule the seas, submarines eat everything else. Submarines eat all the other ships. They sink them and they can’t easily be sunk or spotted by them. But anti-submarine warfare helicopters eat submarines.

Richard: Mm-hmm.

Chris: Because they can try and find the submarines. And a helicopter can kill a submarine a lot more easily than the submarine can kill the helicopter.

Richard: Uh-huh. And so what are these anti-submarine helicopters? What’s the technology involved?

Chris: So I’m still looking into the details a lot more, but there are various ways. So the destroyers and the helicopters, they both use radar. I think the destroyers especially would try and use… well, maybe sonar.

Richard: Mm-hmm.

Chris: And I think that there are kinds of depth buoys that the helicopters would sink down, that they would try to identify... that would maybe acoustically try to identify the submarines. And apart from the helicopters and the destroyers, there are just underwater microphones that are an important element of all this, that both sides have kind of planted everywhere. Underwater microphones that are trying to pick up the noise from any enemy.

Richard: So the submarines have a special noise that other things... Presumably they do, they have a motor or whatever?

Chris: Yeah, and I think one of the advantages of the nuclear attack submarines is that they’re very quiet.

Richard: Mm. Okay.

Chris: So these destroyers, these are the backbone of our fleet, other than the carriers. And one of their main tasks... A destroyer can do it all, it’s a well-rounded ship, large, well-rounded ship. It can do every kind of mission, except...

Richard: So how many do we have and how many does China have, and how many are they building?

Chris: So China has a lot. So let me go to look at destroyer fleet strength by country. This is something that really, only the big guys have these. So as you can see, this site is saying the US has 92 of them. This is actually including our cruisers. This is including every country’s cruisers as destroyers. Cruisers are a rarer class of ship that are larger than destroyers. And cruisers are kind of specialized these days for anti-air defense. So in a US carrier strike group, there will always be one cruiser, at least one cruiser. We have the Ticonderoga-class cruisers, and they bristle with anti-air defense.

Richard: Yeah. So combined destroyers and cruisers, we see US has 92, China, 41, Japan, 36, Russia, 15, South Korea, 12, France, 10, India, 10.

Chris: And the numbers really drop off.

Richard: Yes. UK, 6. Okay. All right. So this is recent you’re saying, China is catching up?

Chris: China is catching up. And these numbers are good to give you a rough picture, but they aren’t quite up to date, and so they don’t fully reflect China’s shipbuilding capacity. So China, I would say China has been the last few years building at least five or six destroyers per year, plus two or three cruisers. China has kind of the best new ship on the seas. China calls it a destroyer, we call it a cruiser because it’s big. It’s the type 055 destroyer. This is the newest, baddest thing on the high seas right now. And China is building a lot of these.

Richard: What makes it cool? What makes it so cool?

Chris: So it’s somewhat stealthy, and it’s big, and it’s modern. It’s got the most modern radar. It can carry a couple helicopters.

Richard: “Return of the Dreadnought,” I do see a picture there. Return of the Dreadnought. The Dreadnought was these awesome giant right ships that apparently they all got... Weren’t they all destroyed in World War I?

Chris: Huh. Yeah, the Dreadnought. I mean, I think those weren’t around by the time of World War II. I think that they might have played a role in World War I.

Richard: Yeah.

Chris: But these things...

Richard: I think they were... I think it was... No, I think they thought they might have a role for them. I don’t know, but it was some either World War I or World War II, they were sort of just discredited as a... I think it might have been World War II, it might have been the navy. It might have been the Pacific battle where people... Yeah, they weren’t around by World War II, so it must have been... I think the submarines killed them. I think that’s what killed them in World War I, because the air power wasn’t as developed.

Chris: So these things, China’s been pumping them out lately. I think it has maybe somewhere around eight active right now, and it’s still building at least two or three each year. These are China’s cruisers. And so I would say between its destroyers and its cruisers, China’s pumping out at least 10 of those each year.

Richard: How many is the US doing?

Chris: The US is capable of making right now about 1.5 destroyers per year. And we are not producing cruisers, we are actually beginning to retire all of our cruisers.

Richard: Mm-hmm.

Chris: We have somewhere around 20 cruisers, the Ticonderogas. But what you have to understand is that they’re ancient. They’re pretty much all at least 30 years old right now, and they’ve got a max lifespan of 40. And I think they generally need a bit of renovation to reach that max lifespan of 40. So the US is in a really big bind right now when it comes to the short term capabilities navally, the numbers over the next several years. A key element of all this, when kind of figuring out the question of what China’s window is to take military action against Taiwan. China’s navy is growing by leaps and bounds. It’s adding at least 10 big ships every year.

The United States is actually losing big ships each year for the next five years or so. This is part of what’s called our divest-to-invest plan. Basically, the Navy is starved of money. There’s this kind of dumb thing going on where the US has these three military branches, Army, Navy, and Air Force. And we have decided for a long time to give them all equal funding.

Richard: Mm-hmm.

Chris: We don’t look at it like, “Oh, what do we need more of? Do we need more of a navy? Do we need more of an army?” They’re all clamoring to be fed. And we have said, “I love you all equally.” That’s how we divide the funding, we say, “I love you all equally.”

Richard: Yeah, that seems dodgy. What are the odds they all need the same thing? Exactly.

Chris: And so our navy just doesn’t have enough money. And so it said, “Hey, if you want new ships, if you want us to design and build new ships, the only way we can do it is by making cuts.” And so what we’ve decided to do is retire a lot of our ships, decommission many of our ships over the next several years, so that we, instead of pouring in money into renovating the Ticonderogas so they can limp along for another five, maybe ten years, we decided to just retire them early. They’re old. We’re going to use that money toward designing and building new ships, which will not be active until the 2030s.

So our navy is shrinking. We are getting rid of our cruisers. We’ve already started getting rid of the Ticonderogas starting several months ago. I think we’ve decommissioned at least a couple of them by now. And over the next several years we’ll be getting rid of the remaining 20. And so this is kind of funny, after China’s naval exercises where it simulated a partial blockade of Taiwan, a couple weeks later, the United States sent our military response by sending a couple of the Ticonderogas cruising through the Taiwan Strait. It was kind of our warning message. And it was meant to be a kind of aggressive warning message, because these are the biggest warships we have.

Richard: Can you pull them up? I want to see what they look like.

Chris: So we sent a pair of these. We sent a pair of these cruising through the Taiwan Strait.

Richard: Yeah, they don’t look as high tech as the new Chinese ones.

Chris: They are old.

Richard: Yes.

Chris: They’re all in their mid-thirties roughly. And the funny thing is, this was meant to be our big warning to China, “Oh look, we’re sending two of our biggest ships right through the strait.” Funny thing is about this threat, if China just waits a few years, we’re going to retire those ships ourselves.

Richard: Yeah.

Chris: We’re threatening them with ancient ships that we are about to get rid of, that will no longer be available if it comes to a fight.

Richard: So people have...

Chris: That’s really kind of a symbol of our toothless empire.

Richard: So, the people in the US, I mean, they’re so worried about China, they’re doing stuff on the chips front, they’re investing in science and tech to counter China. I mean is anybody listening to these arguments and advocating investing more in the Navy?

Chris: Not enough people. It is a hard sell to say that we need to invest a lot more in the Navy. Big question is, where does it come from? I think right now... Yeah, I think in the latest budget, the Department of Defense allocation was actually increased and it was getting somewhere above 800 billion. And so people look at that and say the military industrial complex is a problem, it’s already getting too much money. Especially people on the left will say, “No, we need to have a conversation about cutting defense funding, not a conversation about increasing it.”

And the bigger problem is just the question of allocation. I think that there’s a very clear need for the Navy to be getting the lion’s share of the funding, but we have decided we love all the three branches equally. We will not determine allocation of defense funding by whether we need a navy or an army more. I mean, look an army in a fight over Taiwan? I mean, just look at this big ocean here. How much is our Army going to be helping us in that fight? It’s clearly the Navy that needs the lion’s share of the money.

Richard: And I mean there’s a normative thing there about how much we should be thinking about defending Taiwan. I don’t want to get into that. In this conversation I like this just as sort of a descriptive one, and maybe we’ll do the normative and political stuff some other time.

Yeah. So it seems like... people have talked about... there was a famous article by Ross Douthat not that long ago, maybe a year or two or three years ago. I’m not good with keeping up with when arguments were made, but it was within the last few years. And basically, he was saying that China might just have a window to conquer Taiwan because China’s having a declining population now. I mean because the birth rate is low now. And my response to that is look at the Taiwanese birth rate. I mean if it’s just a comparative thing, Taiwan is reportedly shrinking faster than China.

But the idea was basically they might have a window. And the other thing that people could say is that the US and Taiwan are coming closer together. The Biden administration particularly, they seem to be inching towards greater cooperation. There’s more of a political imperative to defend Taiwan. I think the odds of the US coming to the aid of Taiwan have gone up compared to what it was one year ago, or five years ago, or ten years ago. I think the trajectory is closer US-Taiwanese relations. And so that’s all the case for China having a small window. But then what you’re talking about seems much more important, which is the US can lose Taiwan all at once. If China’s naval advantage is growing year by year, then time is on China’s side, not on Taiwan or the US, right?

Chris: To a degree. So, I do give some credence to these factors like China’s demographic decline that’s approaching, and its potential economic decline that we’re seeing evidence of. So I do tend to believe that China probably has a window, an optimal window for military action that occurs that—

Richard: Well Taiwan’s population matters too, right? Taiwan’s TFR is like 0.9. I mean it’s really low, I mean Taiwan is growing very old, if anything at a faster rate.

Chris: It is a relevant consideration. But I think you’d compare...

Richard: To the US.

Chris: ... Chinese demographics to US demographics more than Chinese to Taiwanese.

Richard: Yeah, fair enough. Okay.

Chris: So, I do lend some credence to these ideas that China is going to have various forces moving against it as we approach the 2030s… demographic, economic. But there are some analyses that have been coming out lately that’s saying this makes China more dangerous in the short and midterm, not less. Because historically there are analyses that a power is less likely to take military action if it foresees itself just growing stronger indefinitely.

Richard: Mm-hmm. Right.

Chris: If it’s growing stronger indefinitely, just be patient, wait, and then keep throwing your weight around and bully people without attacking.

Richard: Well, I think this is what happened with Russia and Ukraine. I think that what Russia saw, that Ukraine was coming closer to the US, the US was arming it better. Ukraine was building a real military, the drone situation. There was a great article by Rob Lee, I forget where he wrote it, but this I think what was happening with Russia, right? I think Russia saw that Ukraine was sort of shifting out of its orbit, politically and sort of militarily it was going to be in a worse situation as time went on.

Chris: Yeah. And so I give credence to that. And I think that as far as the naval situation goes, it’s a key consideration that trends favor China if it just waits a few years, as its navy continues to grow rapidly by leaps and bounds. And we actually are intending to shrink our navy. We are beginning to shrink our navy, and our navy is going to reach a low point somewhere around 280 ships by the year 2027. And so I’m really looking at somewhere around 2027 as the window of maximum danger, because we’ve kind of telegraphed our intentions. When it comes to building ships and retiring them, you have no choice but to telegraph your intentions, because these plans take years in advance to design and implement. And so everybody knows that our navy’s going to be at its weakest sometime around 2027, and there’s really not much we can do about that.

Explaining Zero Covid

Richard: Yeah. And the economic growth thing, I mean China has had 40 years of catching up and that a bad... Recently the zero COVID stuff. But I think that they think... I don’t think they’ve given up on the idea that they’re going to keep growing at a faster rate than the US. I mean, I think they have reason to think that they might be able to. So yeah, we’ll see. I think the zero COVID thing is just so interesting, because it’s harmful to economic growth. And if you think that China wants to maximize its power globally and its military capabilities, you’d think they would prioritize that a lot, but they seem to not... I mean, they’re explicitly saying “we’re not prioritizing economic growth.” And it seems like a lot of the things they’re doing are consistent with that. So what do you make of that? It seems a little bit crazy.

Chris: It is a bit of a puzzle. I mean, if I were in charge, that’s probably not the way I would play it.

Richard: Yeah.

Chris: But they have their own priorities and I’m at a loss to explain why zero COVID is such an incredibly high priority for them. Do you have an explanation?

Richard: Actually, I was going to write a... I was thinking about writing a substack on this, and I think there’s three, I guess I’ll preview it now. If I actually do it, I still don’t know. I always have 10 articles in my head and then I pick one. So this is one that might actually be an article. There’s a few theories. Number one, all they care about is maintaining control of the population. The zero COVID is actually very useful for that. So they have these QR codes that you have to scan everywhere you go. There was a story in the New York Times that somebody... people were trying to protest the government and they changed their QR code from green to red. And when it changes to red, apparently you can’t be out in public or something, you have to isolate. And they didn’t plan this probably from the beginning, but what a power in the hands of the government to say, “Okay, public health, Chris Nicholson, you go home for a month.”

You just have that regime, that’s a lot of power. That’s a lot to give up. So it’s a social stability kind of thing. People say stuff like, “Oh zero COVID is their pride,” and they want to prove that their system is better than the US. Okay, I think you made your point that you can handle COVID better than the US, so I don’t know why you have to keep doing that indefinitely. It just seems sort of crazy and it discredits the system. So I don’t know if that argument makes sense. So I think the control argument makes sense. I think the argument that it’s just a national pride thing. We just had the Communist Party conference. It’s still going on right? The National Congress. And so that’s one of the theories that it just has to... when Xi Jinping gets his third term, they’ll switch up. So it’s just a personal accomplishment for Xi Jinping.

That’s a possibility. We’ll know more in the next months and the next year or so. And so maybe that political argument would make sense if we see them relent. If they keep going after Xi Jinping securing his third term, we’ll have to keep... we’ll have to think about the other theory. So the other theory is our number one, control. So just going back. Number one, control. Two, the pride and the accomplishment through zero COVID. Three, and this is maybe the funniest but of the most horrifying possibility, well, maybe they just really think it’s a good policy. Maybe they just want to save as many old people as possible, and they think economic growth and living a good life is overrated. And there’s a quote from Xi Jinping in his last speech at the Congress where he’s just like, “We put lives over other considerations, and we showed the superiority of our system,” or something like that. What if this guy actually believes that? Maybe he does. And so that’s another possibility that I haven’t seen people take seriously, but it’s just like they’re just hysterics about COVID and they just want to protect their population.

Chris: Yeah. We’ll have to see how it develops. They always have the choice of reversing course or softening the zero COVID approach, if they think it comes to affect them too much economically, and if it starts to infringe on their military development too. Now the semiconductors—

Richard: Maybe it doesn’t have to be a tradeoff because it’s just like... they really prioritize saving lives in COVID, they really prioritize the military. So we’re just going to see a lot of the budget go towards the military no matter what, even if the growth is relatively low. And they’re going to sacrifice a lot of GDP for COVID too, right? I mean, they’re just going to something where they don’t care about growth and they’re going to focus on these two priorities.

Semiconductor Warfare as a Sign of Desperation

Chris: It’s certainly possible. But Biden’s aggressive semiconductor warfare starts to come into play here, because whatever margin for error China had economically and militarily, begins to shrink when you now consider this new semiconductor warfare we’re playing against them. We’re basically trying to cut them off at the knees with the entire semiconductor supply chain. And I think that’s closely linked to the military situation that I’ve been laying out for you. I have been laying out a grim picture where the naval momentum, the military momentum is entirely on China’s side and against us.

And I see Biden’s semiconductor maneuver in the light of all that. Where basically we are saying is we cannot catch up to China as far as the shipbuilding trend goes. We cannot. We don’t have the capacity, we don’t have the industrial base here to create more shipyards and staff them. The staffing is a major issue, especially. It takes a lot of work to train the people to be able to build these ships. China is exceptional at that. China is the world’s leader in shipbuilding, civilian and military, and they’re integrated. We just cannot catch up in that battle. And so what I think we’ve decided to do is slow China down. And we’re slowing them down by starving them of the advanced chips that they need to create the most advanced ships and planes and rockets and missiles. That’s how I see the move. It’s a move of desperation. We cannot catch up, and so we are slowing them down.

Richard: Yeah. I mean the problem is, this is a very technologically capable country. China, I mean it passed the US on the Nature Index. So the Nature Index takes into account just not number of scientific publications, but also how cited they are, so as far as we have measures of comparative and scientific output. Things like number of engineers they’re graduating a year. I mean, some of the biggest tech companies are from China, Alibaba, and Huawei, they’re very capable. There’s a lot of people, it’s a big market. Yeah. I mean in the long run, I don’t know. That’s a very smart country with a lot of people and it’s very good at science and technology and could the US and Europe be ahead of them forever? Yeah, it seems unlikely.

Chris: Forever? Probably not. But in the short to midterm, we can hurt them badly by starving them of—

Richard: Yeah. So 10, 20 years maybe you hurt them, and then who knows what happens then? In a hundred years, China maybe is destined to be the world leader in scientific innovation, but who knows what’s going to happen by then.

Why Care about Taiwan?

Chris: So at the center of all of this, of course, is a thing we haven’t mentioned, I think we probably assumed that our reader, our listeners know this. Our entire interest in Taiwan is about its semiconductor fabrication capabilities. We may say it’s about defending a fellow democracy. That’s just kind of the polite thing we say publicly, because it sounds a little crass to say, “We need them for their semiconductor fabrication.”