I have a new report for Defense Priorities called “Phantom Empire: The Illusionary Nature of US Military Power,” that’s also featured in the Politico newsletter National Security Daily.

The main argument is that much thinking about American military commitments abroad is based on faulty reasoning. The US incurs costs and takes serious risks for little gain, in part because American elites want to defend foreign countries, sometimes more than the nations themselves want the help. The highlights:

The US has become a “Phantom Empire,” a country that appears to be powerful because it has a robust military presence abroad but cannot use garrisoned forces to achieve geopolitical objectives.

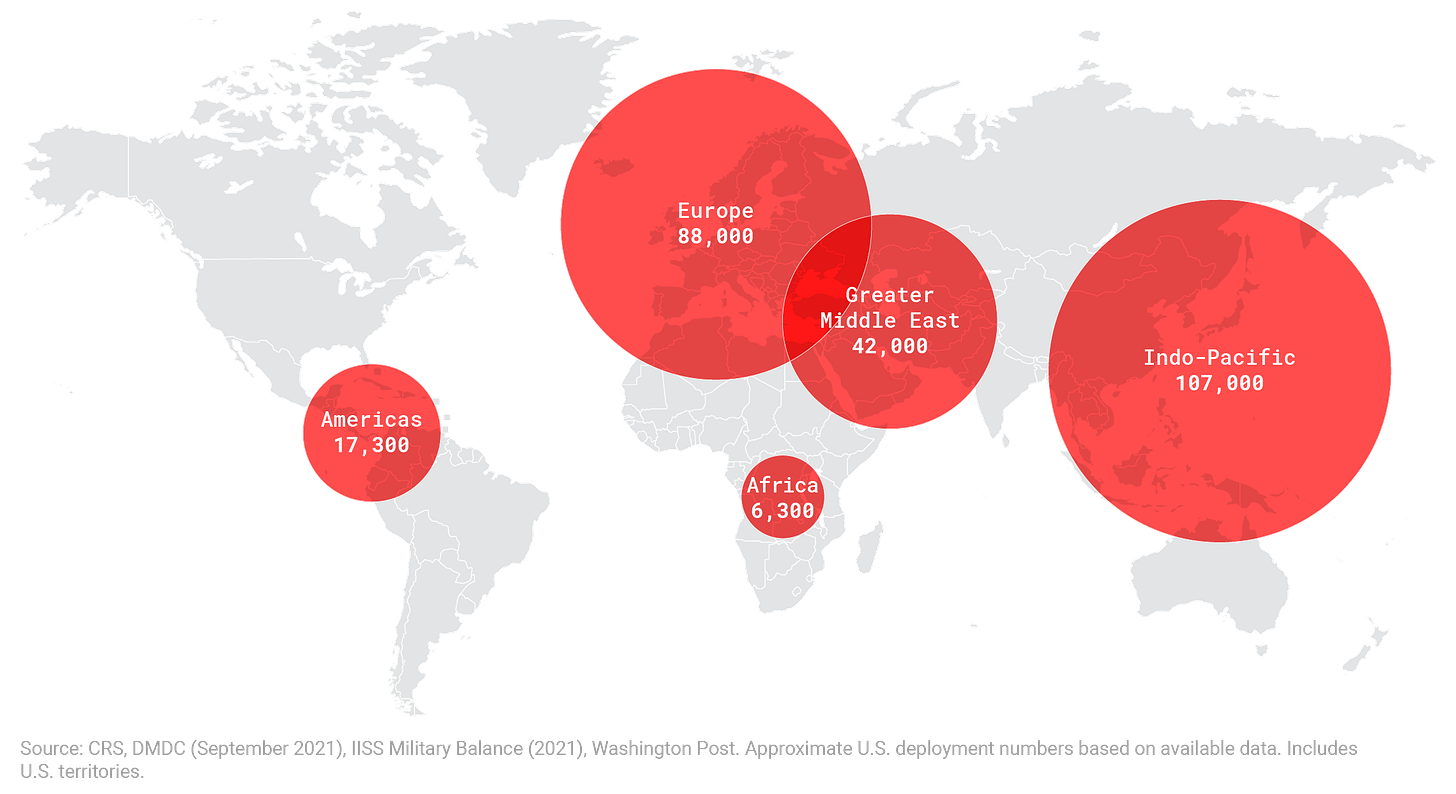

More than 225,000 US troops and DoD personnel are stationed abroad in more than 175 countries. The largest deployments are to wealthy US allies (Japan, Germany, and South Korea) capable of defending themselves.

US leaders often justify military commitments by arguing they preserve “influence.” But because American leaders are committed, in most cases, to maintaining troops abroad as a good in and of itself, the US squanders most of its leverage to influence hosts. Threats to withdraw troops are not credible, making them irrelevant for most US geopolitical goals.

The sources of US power and influence are ultimately rooted in economic prosperity and soft power. A foreign policy that cultivates these sources of strength over maintaining military commitments would better achieve US geopolitical goals.

I discuss these ideas in the context of American foreign policy in Europe, the Middle East, and East Asia. Read the whole thing here.

In other news, two excellent articles recently appeared in City Journal that cite my article Woke Institutions is Just Civil Rights Law, one by Charles Fain Lehman and the other by Gabriel Rossman. Glad to see the idea that opposition to wokeness has policy implications being taken more seriously.

Finally, I recently got a lot of new subscribers (thanks Tyler). For those who are not on the mailing list of CSPI, the organization that I run, you should get on that too, as we’ve been doing great work.

One possibility is that elites are more activist than the public. They station troops in county X in order to give the public a stake in country X. The troops are a "tripwire," for example. If some of our soldiers are killed, the public will want to retaliate, and that gives elites leeway to be activist.

Under this hypothesis, it does not bother the elites that the troops fail to enhance our influence with country X. The actual goal is to influence American domestic opinion. If the public believes that X is our friend (they host our troops, don't they?), then this gives elites more leeway to engage in activist policy--make deals with X, give aid to X, etc.

Maybe this is too cynical.

Having worked for the U.S. Military overseas my observation from ground level is that the public has a love/hate attitude towards them being there. Small businesses and landlords love the money GIs spend in the local economy. The U.S. also spends a lot of money to rent the bases and mitigate the effects of our presence. There is also a SOFA (Status of Forces Agreement] that stipulates, among other things, how many locals are employed at the base and in what capacity. This varies from base to base. Some of the locals like us but most don't. They see GIs as rude, invaders, and as the WWII British used to comment "Over paid, over sexed, and over here". GIs are almost never held to local account for any laws they break other than traffic, an never go to jail for more than overnight because the Military Police come and get them and they are often hustled back to the States quickly. Also, the Americans tend to be insular, mostly hanging out with eachother.