Free Speech Should Be a Masculine Virtue

The problem isn't oppression, it's that men are now cowards

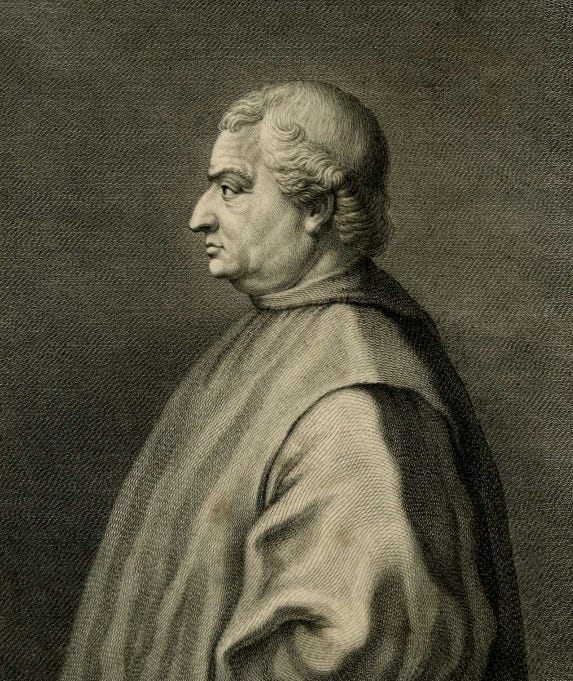

I’m reading Virtue Politics by James Hankins, about the political ideas of Italian Renaissance thinkers. This passage crystallized something I’ve often thought about, and helped me understand what I find distasteful about the modern free speech movement.

For example, humanists did not think of free speech as Americans do today, as a right guaranteed by law and protected in the courts. For them it was a virtue, speaking truth to power. For the statesman and diplomat Alamanno Rinuccini, free speech was closely related to the virtue of courage:

No one would call free the man who either in the senate, the assembly, or the courts would be constrained by fear, cupidity or any cause you like from daring to say openly what he thought and to act on it, so that, as I said before, someone might claim without absurdity that freedom is part of fortitude, since the free man and the courageous man are best revealed in action. The brave man is praised for undergoing grave perils in accordance with reason; the free man is manifest more in speaking and giving counsel; yet the duty of the noble soul is revealed in both the brave and the free, since neither one gives way before dangers nor lives in fear of threats. It is an extremely useful thing in free cities when citizens, in giving counsel, give their undisguised views on what is best for the republic.

To speak with freedom, to advocate what was right, especially before a tyrant or a howling mob, was a great virtue that required other virtues such as prudence and courage. It could proceed only from a strong soul that cared for the right.

Yglesias notes that many academic historians have privately told him that they secretly agree with David Austin Walsh’s comment that white men have a harder time getting jobs in academia. What I find interesting here is not that individuals might be cowed into silence, which happens. Rather, it’s that they have no shame about this fact.

When I spent more time around academics, I often used to hear some variation “of course I agree with you, but I’d never be able to say that!” To me it’s like hearing someone say “you know, I couldn’t satisfy my wife last night. Us guys with small dicks, am I right?” Sure, anyone could have one bad performance, but to indulge in it is weird. This is especially true if you chose to go into the world of ideas as your profession. To me, this comes with a sacred duty to tell the truth that is fundamental to my personal identity.

There is of course a difference between courage and suicidal recklessness. Think about men on a battlefield. We praise a soldier who puts his life on the line in order to pull a wounded comrade to safety. If a guy simply rushes into a hail of machine gun fire with no strategic purpose behind his actions, he might still be brave but we consider his stupidity more notable than his courage. There would likewise not be much value in trying to save a wounded comrade if there’s a 100% chance you will not be able to do so and probably get killed in the process. Courage as a virtue we might say involves taking some measure of reasonable risk for a higher purpose or goal.

For that reason, I don’t advocate people go through life simply blurting out whatever pops into their heads. If you are a junior scientist working on a project to cure cancer and have a disgust towards transgenderism, your obligation to yourself and society requires you not to shove that opinion in the faces of liberal colleagues. Yet I think people in the world of ideas have a special obligation, and most of them could be much more courageous on the margins.

Sometimes I’ve heard academics or businessmen say they like my work but can’t admit it. At the same time, I see people who seem similarly situated but are interacting with my tweets openly and under their own names. The difference here is one of personal character, and norms should encourage more rather than less personal bravery.

In America, you’re not going to be arrested or executed for your political views. If you’re a tenured professor, you won’t even lose your job. Free speech advocates will often complain about subtle forms of discrimination they face as someone with unconventional views. Yet imagine if we talked about gun rights this way. Nobody would claim that their Second Amendment rights were violated because their social circle doesn’t like firearms, and others might not want to date or hire them if they bought a gun. Most people would naturally respond that this sucks for you, but government exists to protect your right to do something, not shape attitudes towards your actions. A more direct analogy might be the LGBT movement, where a right to be left alone transformed into a right to demand acceptance from others and to infringe on their property rights.

If you believe that your free speech rights are violated because other people might not like what you say, I really don’t have much sympathy. Truth and a need for self-expression are simply not that important to you. That’s fine, and I don’t begrudge anyone over this. I don’t believe everyone can or should be an intellectual. But what’s really pathetic is to see someone put what must be at least 20 hours a week into a twitter account while being anonymous. Clearly, self-expression is important to you. But you just want all the benefits of participation in the marketplace of ideas, with none of the risks or potential costs. As someone who is openly in the public sphere, I see right-wing anonymous accounts as engaging in a kind of stolen valor.

One could argue that we should build a broader culture of tolerance because people saying what they think is a social good. We can approach this question by asking what kind of world we want: one where only the brave express their views, or one where everyone feels comfortable doing so? In other words, can the marketplace of ideas use more input from individuals who are personally cowardly? The thought of a society where you can only express your views if you’re willing to take on some risk appeals to me. At the same time, creating such a world may mean that the craziest and most reckless individuals dominate the public sphere. Arguably, this is what we see with MAGAs on the right and wokes on the left. You may think that the justice system goes easy on BLM protestors, but there’s no world where an urban professional with a comfortable life throwing a Molotov cocktail at a car isn’t brave. Likewise, no faction within conservatism has taken more risks in recent years than the January 6 rioters, even if they were delusional in their beliefs.

We arguably need stronger free speech norms, then, to give the less brave and reckless – and hopefully more sane – a fighting chance. The problem with this argument is that it makes no demands on those who want to be listened to and rule. It selects for a more cowardly elite. Rather than lower standards and demand the public arena make room for the mentally weak, I’d prefer a project to try and instill masculine virtue among individuals with the traits necessary to rule society. This is not something anyone is even trying to do. Ezra Klein talks about how he has no idea what a left-wing version of Jordan Peterson would look like, given that liberals don’t really have a positive vision of masculinity. Conservatism is less conflicted on this issue, but its version of masculinity has no place for stoicism in the Trump era. I find few things to be more unmasculine than exaggerating the problems and challenges one faces. Right-wing spaces are nonetheless filled with individuals referring to themselves as “kulaks,” “dissidents,” or “heretics.” In a way, Trump is the perfect leader for this movement, in that he has all the vices of masculinity and few of the virtues. MAGA populism looks at what happened to Alexei Navalny and says that this only reminds us that the real victim is Trump, and I wonder how much their aggressive callousness towards the victims of Putin reflects the shame of individuals play acting as freedom fighters getting angry when confronted by the real thing.

There is in the end something deeply defeatist about the argument that we have to make room for the cowardly because they have at least as much to contribute to the marketplace of ideas as the brave do, if not more so. It assumes that we can hope for individuals who are either courageous or smart, but not both, and to get more intelligent input into public discourse we need to be working all the time to make sure nobody is ever “discriminated” against for holding an opinion. Like all other anti-discrimination crusades, this one has the potential to be open-ended, create new classes of designated victims, and become hostile to individual liberties.

It would be much preferable to cultivate masculine virtue in people who are smart, moral, and have good epistemological habits. Since contemporary Americans don’t face any substantial oppression based on political views – MAGA hysterics notwithstanding — this project would involve finding inspiration from earlier historical eras and different parts of the world. I keep going back to the Enlightenment, when ideas about freedom and individual liberty were still new enough to intoxicate intellectuals and motivate them to act with courage. When the American Founders pledged “our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor” to the cause of independence, they weren’t just motivated by a love of individual liberty in the abstract, but a sense that as men they were called on to behave in a certain way. It’s not even the point that they actually faced any risks. Rather, it’s that they lived in a cultural environment where the entire idea of being a man meant that you behaved in a masculine way and stood up for the rights of yourself and your community. I think they would’ve seen being cowed into silence as a mark of personal failure, rather than something to joke about with friends.

Another place to look for inspiration is in pro-democracy movements across the world. In places like Ukraine and Myanmar, more liberal forces have shown at least as much bravery as reactionaries. I used to mock the mawkish sentimentality of those who talk about things like the march of democracy and the rules based international order. The Bush era taught us how dangerous utopianism in foreign policy can be. At the same time, people need inspirational stories to motivate them and guide their values. In the US and Europe, most of our problems are caused not by overt oppression, but bad policies and misaligned incentives that usually have good intentions. It’s difficult to motivate people to get angry about such things. Fighting Putin or Hamas is more inspiring than fighting NEPA or the FDA, and perhaps hating foreign enemies can create the culture that leads to needed technocratic solutions by reminding us of the importance of freedom and the fact that you as a Westerner are not all that oppressed from a historical perspective. If you’re still afraid, then the problem is you.

I think that your division into masculine (and presumably feminine) virtues is part of the problem. We have too many cowards in society, period, and a good many women think that they get a free pass on this, because courage is somebody else's problem. Or worse, that there _are_ courageous people is the problem, in a world where cowardice is called a virtue, such as 'being agreeable'. Courage is for everybody. Daughters need to be taught how to be brave, too.

I love this essay. So much here. Minor point: The masculine virtue is a combination of speaking truthfully and openly under one’s own name combined with some sense of honor, epistemic integrity, and civic virtue. Conflating this with free speech alone seems off. Free speech is the foundation for this virtue but not the virtue itself.