Gerontocracy Versus Western Civilization

How laws benefiting the old are robbing the world's most successful societies of what made them unique

In discussing the motivations behind China’s Zero Covid policy last month, I put forward three possibilities. Two of them – the idea that the policy is a source of pride and that it allows the government to control its population – tend to get a great deal of attention. A less common view, argued for by some defenders of the CCP if no one else, is that Zero Covid is actually a good thing for society, or at least that the government thinks it is.

Consider that people don’t like to make tradeoffs. A politician in the US who got up and said “choose this policy, it’s going to kill many more people, but you’ll have more economic growth and a higher quality of life,” would probably soon be out of office. Every time there’s a school shooting, Republicans don’t just tell people to accept that such incidents are an inevitable part of living in a free country; they latch on to some nonsense like “door control.” Why can’t Chinese leaders think the same way? What if their people do?

Part of the bizarreness of Zero Covid is it goes hand-in-hand with a subpar vaccination campaign. If you can force entire megacities to stay home because you’re worried about a disease, can’t you mandate, or at least heavily incentivize, those most at risk to do the one thing that is most sure to protect them?

There is one possibility that would explain both Zero Covid and a lack of interest in vaccination: China is a gerontocracy. In other words, it has a government that is especially prone to being influenced by old people. That’s not the same thing as doing what’s best for old people, since, after all, a more effective vaccination campaign would be in their interest.

To me, this is much more frightening as a possibility than the idea that the Chinese are, as many in Washington seem to believe, a race of super geniuses with a thousand-year plan to take over the world. Of all the things to try and optimize for, “keeping old people alive as long as possible” seems to be among those most likely to lead to a dystopia, as can be seen in the fact that about a quarter of the Chinese population is reportedly under some form of lockdown.

But if Zero Covid can be explained by China being a gerontocracy, it would indicate that they’re not that much different from us. Usually, public policy tries to come down on the side of the group that is seen as disadvantaged, such as blacks relative to whites, the handicapped relative to the able-bodied, or the poor relative to the rich. Yet old people are the wealthiest and most powerful demographic in the United States. Despite this, they are overwhelmingly beneficiaries of the welfare state, have seniority rights in employment, and are a protected class when it comes to anti-discrimination laws. This essay argues that this is a bad thing, and those worried about progress, identity politics, or burdens faced by young people should focus more on the advantages society gives to the elderly.

Criticizing boomers is fashionable, with advocates of generational warfare often blaming the old for being unwilling to pass the baton to future generations. Yet their complaints are generally superficial, directed towards things like calling for younger political leaders and CEOs. Of course, very few Americans achieve such prominent positions, so that while people might want “representation” at the top levels of society for aesthetic reasons, the demographic makeup of those who rule over us has at most an uncertain and indirect influence on policy. The generation warriors resemble wokes in disproportionately caring about who gets a few prominent jobs while usually missing the larger picture. In the process, they ignore the extent to which our entire system of governance revolves around favoring the old at the expense of the young.

The Federal Government is Welfare for Old People

Social security takes 12.4% out of the paycheck of each worker, on earnings of up to $147,000. Half of that is covered by employers. The program gives money back to people when they retire, starting at age 62 at the earliest, though a minority of recipients are younger and disabled. Medicare, which provides healthcare coverage for those 65 and over, takes 2.9% of whatever workers earn, again split between an employee and his firm.

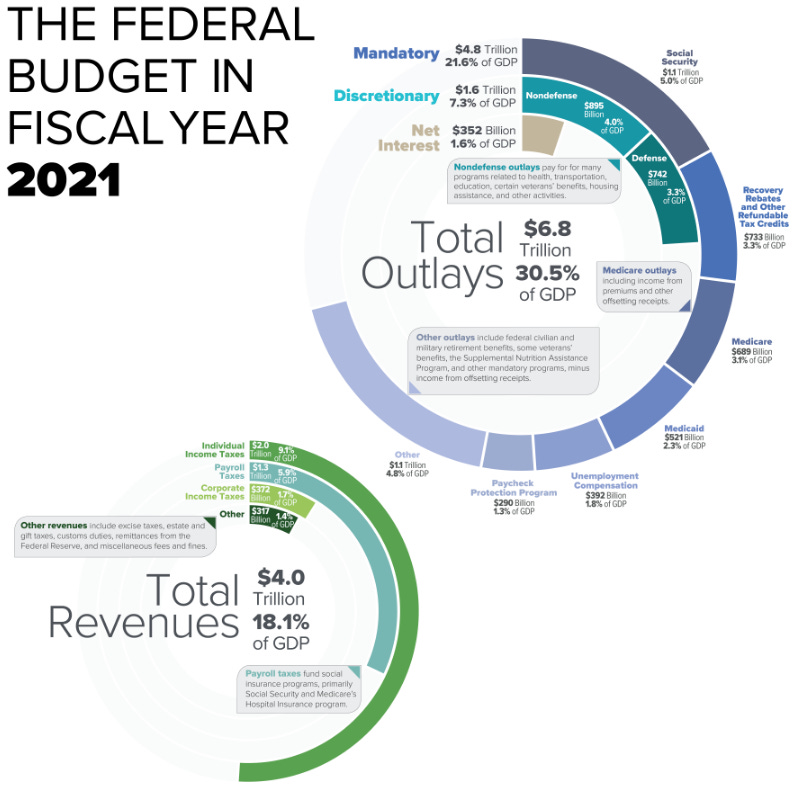

It is projected that this year about a third of the US federal budget will be spent on these two programs alone. Those 65 and over make up only 17% of the population. Of course, the elderly also benefit from other parts of the federal budget; the portion that goes to Social Security and Medicare simply represents what is earmarked for them. These programs together consumed 8% of GDP in 2021.

Social Security and Medicare can be seen as either redistributing money from the young to the old, or, in what amounts to the same thing, transferring money across an individual’s lifespan to their later years. This goes against the normal logic of the welfare state, in which we try to redistribute money from the rich to the poor. It’s not just total wealth, as age is also correlated with income for those of working age, meaning that future retirees are in a good position to save money in the years immediately before they leave the workforce.

Of course, these differences exist under the current entitlement system. The gaps would presumably be reduced if people were forced to save for their own retirement, though there is little reason to think that they would disappear completely.

Even putting aside the fact that the elderly are financially better off than the young, there is something particularly perverse about taking money from people when they’re in the years during which they can invest in themselves and their families and giving it back to them when it is least useful. Women only have 25 years or so of adulthood during which they can have children. Men remain able to reproduce for longer, but usually they are close in age to their partners so their time is also very limited.

As the elderly population rises and medical costs grow, entitlements are becoming ever more expensive. The net impact on the federal budget due to Social Security and Medicare is expected to rise from around 2.2% of GDP today to nearly 4.4% in 2040. Note, that’s not total spending on the programs, which is much higher, but the costs that are not covered by incoming revenue and must be borrowed, with the government thus committing yet another sin against future generations.

Anti-Discrimination Laws and Seniority Systems

You’d think that since the government showers so many benefits on the old and tries to make retirement as comfortable as possible, it would at least combine this with attempts to push them out of the workforce sooner to give young people a chance. In fact, we do the opposite, which contributes to a perverse system in which young adults have to hand over part of their paychecks to elders who get not only large welfare benefits, but artificial advantages in the labor market.

The Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967, modeled on the Civil Rights Act, banned discrimination against those between 40 and 70 years old in hiring, firing, and promotions. A 1986 amendment to the bill removed the cap of 70, and ended mandatory retirement in most industries. As with most civil rights laws, age discrimination has been interpreted to include actions taken that have a disparate impact.

People’s brains deteriorate as they get older. This is likely to be particularly noticeable in the most cognitively demanding jobs. It is unsurprising, then, that employers in science and tech industries are often targets of age discrimination lawsuits. In the 2008 Supreme Court case of Meacham v. Knolls Atomic Power Laboratory, a federal research lab ordered a contractor to downsize. It therefore told supervisors to rank employees in terms of their performance, flexibility, and importance of skill, even adding points for seniority. Management ended up firing 31 employees, all but one of which were over the age of 40. The Supreme Court ruled that the burden of proof was on the employer to show that it based its actions on “reasonable factors other than age” given the statistical pattern.

Within this legal framework, IBM is currently being sued for attempting to move towards a younger workforce and keep up with its rivals. The CEO had adopted this strategy as a way to become more competitive in areas like “cloud services, big data analytics, mobile, security and social media.” In 2020, the EEOC found that IBM took “an aggressive approach to significantly reduce the headcount of older workers to make room for Early Professional Hires.” The year before, Google settled a class action lawsuit brought by 200 older job applicants for $11 million. Oracle was being sued around the same time for a program to actively hire recent college graduates on the grounds that they were to replace older workers. This is all despite the fact that, as of October, the unemployment rate for Americans between 25 and 34 was 4%, significantly higher than the 2.5% it was for those 55 and older. Youth unemployment is an even bigger problem in most of Europe, where labor regulations are more stringent.

Anyone who has ever seen an elderly relative fumble with a touchscreen has to sympathize with tech companies trying to transition to a younger workforce. It is little wonder that IBM can’t compete with Google in cutting edge industries. It is a much older company, and therefore cursed with unproductive employees it can’t get rid of, while this is less of a problem for more recent arrivals. Although age discrimination laws apply equally to hiring and firing, in practice it’s probably easier to legally justify relying on objective criteria in the hiring process, as an initial rejection by a firm is much less likely than cutting ties to cause feelings of anger, which can lead to a lawsuit.

Old people are not only protected against younger workers with better brains, but also those with better bodies. A few years ago, five female journalists between the ages of 40 and 61 sued the local TV station they worked for alleging that they had been pushed aside for younger women and men, thus stating claims of sex and age discrimination. Social norms, and sometimes legal prohibitions, against placing a premium on beauty in the labor market exist to the detriment of younger, particularly female, workers. There’s an old Rush Limbaugh quip that feminism was created “to allow unattractive women easier access to the mainstream.” But it’s generally older women that benefit from the prudish, sex-negative aspects of feminism.

Advantages in brains and beauty are given to the young by nature. Anti-discrimination laws try to level the playing field in these areas, while our legal system also actively creates and protects artificial privileges bestowed on the old. Collective bargaining agreements regularly include seniority systems, where workers who have been in a job the longest get the most pay and are least likely to be fired when cuts need to be made. In the 1970s, there were prominent court cases in which plaintiffs alleged that these systems were racially discriminatory, since in industries and firms where blacks had historically been excluded, seniority had a disparate impact effect. Nobody of course has ever cared that the principle discriminates based on age, since we take it for granted that the job of governments and institutions is to give special privileges to old people at the expense of the young.

This is the context in which one should understand data showing that the average age of scientific grant recipients is increasing over time.

IBM, as a private firm, has at least tried to modernize by moving towards a younger workforce, even if it is having to fight tooth and nail to do so. Universities are not subject to direct market pressures in the same way, so they’re unlikely to provide even token resistance to anti-discrimination laws that require institutions to keep employing older workers at inflated wages. Being unable to institute mandatory retirement policies since 1994, universities are forced to keep on less productive professors or waste funds on paying them to leave. Of course, while brains and energy deteriorate, CVs only get longer, so older academics are perfectly situated to compete for grants distributed by far-off institutions that are in a poor position to monitor how recipients function on a day-to-day basis. Younger researchers do most of the work, taking advantage of the networks and reputations built by more established scientists, with the latter nonetheless getting most of the credit and becoming even better able to compete for scarce funds.

Gerontocracy is the Enemy of Western Civilization

The age issue is different from other kinds of identity politics. As mentioned, old people are the wealthiest and highest-earning demographic in the country, with the lowest unemployment rate. And there’s no case to be made that they – unlike homosexuals, blacks, or women – should get special privileges on account of being historically disadvantaged. In fact, across time they have generally had more power than young people.

We’re obviously wired to give the old special deference. In earlier stages of human development, this involved patriarchal clan-based systems and ancestor worship. Today, we express our respect for age through government budgets and the court system. But this is clearly a case of pathological altruism. We redistribute resources and opportunities away from those that need it most to those that need it least, and make it more difficult to support, or even create, future generations.

In The WEIRDest People in the World, Joseph Henrich points out that one of the secrets to the success of Western civilization has been that it gives less deference and respect to elders than other societies. This allows men more opportunity to compete for resources and mates earlier in life, with “males becoming heads of households at younger ages and new wives moving out from under the thumb of their mothers or mothers-in-law.” In a footnote, he discusses the uniqueness of our notion of retirement, when “people lose their leadership roles and economic centrality,” as opposed to most non-Western societies, “where the elderly remain economically and socially central unless they become cognitively impaired.”

Ironically, welfare for the elderly, seniority systems, and anti-discrimination laws can be seen as the West moving away from what made it special and reinventing the norms and forms of entrenched privilege that are the hallmarks of less successful societies.

Of course, there’s no denying that the reason government programs that benefit the elderly exist is because they’re popular. And old people vote. While economic self-interest is usually a poor predictor of political views, there tends to be an exception when the consequences of a policy are direct and absolutely clear. While everyone opposes making major changes to Social Security, the elderly are the most resistant segment of the population.

It’s funny how little attention the age issue gets given our obsessions with identity politics. People seem more willing to unthinkingly accept special privileges based on age than race or sex. Partly this is because all of us start out young, and if we’re lucky we get old. So there’s an idea that entitlements are just moving money around within the same lifetime. Yet, even putting aside complicated philosophical questions about whether the unified self is an illusion, 19% of Americans die before the age of 65. This means that around a fifth of the population can expect to get absolutely nothing from the two entitlement programs that are eating the federal budget. Of those that do make it to Entitlement Heaven, there is of course wide variation in how long they stay there.

An additional psychological predisposition that I think has led us on this slouch towards gerontocracy is the status quo bias. A seniority system intuitively strikes people as a good thing because they care more about preserving what individuals have than creating new opportunities. This goes back to the point that overly broad anti-discrimination laws are easiest to enforce at the firing stage. Similarly, a retiree having to reduce his standard of living after leaving the workforce seems more regrettable than a young man having to wait longer to buy his first house. While this impulse is understandable, indulging in rather than struggling against it is the path to stagnation. The story of Western civilization can be told as the heroic triumph of the one people that fought the status quo bias rather than allowed it to strangle progress. Unfortunately, allowing the market to redistribute power and resources from the old to the young is just another form of creative destruction we’re no longer able to bear.

Despite the difficult politics involved, those who are concerned about low fertility or wealth gaps between generations, or economic and social dynamism more generally, are going to at some point have to directly take on the gerontocracy. While wanting to protect the elderly is part of human nature, so is the belief that we should care for future generations. Most old people don’t want to be burdens on the rest of society. But that’s what they’ve become.

Another thing that’s strange about the politics of age is that usually movements want to claim the mantle of the “protected” class. So politicians will brag about winning Hispanic women, but feel ashamed if a disproportionate share of their voters are white men. Yet the elderly are in one sense part of the victim class, being protected by anti-discrimination laws. At the same time, political movements usually feel better about themselves if they can win over the youth vote. This indicates that, while people support welfare for seniors because they support welfare more generally, if someone wanted to push for age to become a more salient divide in our politics, there could potentially be more sympathy for younger generations.

Most writers who support generational warfare stick to very safe recommendations that sound good to most people. To them, going to war against the gerontocracy means picking a battle with a few rich white guys, always an easy target, with the assumption being that if we had younger leaders things would somehow change for the better. But those who would replace our aging elites would in all likelihood continue the same policies that got us here. The problem isn’t the successful business leader or politician. It’s the social security recipient who is able to stay in a house with two extra bedrooms he doesn’t need because of monthly government payments taken from couples deciding whether to have a second baby. Or the nice professor who is well-liked on campus and generous with his time but still paid and treated as if he’s one of the best researchers in the world when he’s functioning below the level of the average PhD student who won’t be able to find a job after graduation.

Those advantaged by our current system are generally sympathetic. But they still benefit from unearned privilege. I await a true youth movement that not only understands the problem of gerontocracy, but is willing to advocate for the difficult choices that need to be made in order to regain the dynamism that the West has lost.

You make some good points. But most people like their parents and don't want to see them poor and ALSO don't want to be personally responsible for their care/support in retirement.

And practically speaking if you told me "Hey we're cutting your parents off from SS and MCR and also no SS or MCR for you either but ur getting a 15% raise." I would not be excited and suddenly feel like I could afford more children.

U seem to be leaning towards death panels and assisted suicide to help lower the costs of health care spending on the super old. I get where u are coming from, just not sure it is the right approach. Perhaps doctors explaining to patients more about expectations and realities so that older folks can be smarter about decisions. Although that may not work either since elderly Doctors (who should know better) seem to statistically be no different than regular folks when it comes to "Do anything u can to save them" mentality.

Correction: Most old people don't want to be burdens on their relatives, but they are perfectly happy to be a burden on society as they demand their social security and pension checks. They merely displace the burden from someone they know to the anonymous everyman.

But in reality social security taxes the working age young parents who should be having children. They have fewer children because of the tax burden to support the elderly.

Such societies will all collapse due to lack of children in about 4 to 5 generations from the initiation of socialism. This is being seen in both China and Europe.