Note: I’ve struggled with whether to paywall stuff and how much. I’ve come to the conclusion that for articles going forward, I’ll follow a rule where I keep those of general philosophical, policy, or social relevance free to everyone. But I’ll paywall the ones that are mostly of a personal nature or have a self-help component. As you’ll see in the opening paragraphs below, this article is sort of on the border between the two categories, but I’ve decided to place it in the second one.

I’ve been busy with book promotion stuff, but have been meaning to get my thoughts down on the experience of not being cancelled, and what people can learn from it.

The week it happened, people would text me and ask how I was doing. My response was always that it’s not pleasant but I’m less stressed about it than the vast majority of people would be in my situation, which was true.

I know that this is how humans show affection for one another, and people’s intentions were good so I don’t get upset with them, but I have such an aversion to thinking of myself a victim that it makes me uncomfortable when people check on me. I try to keep bad news from my personal life completely private, and when something bad happens and a person who is close doesn’t reach out, that’s how I know they truly get me.

I always knew that something like this could happen, and now that it has, it provides an opportunity to share some thoughts on where I think cancel culture is going and what the landscape now looks like in terms of free speech and attempts to “unperson” individuals who have said politically incorrect things. I do this in the process of writing what is essentially an advice column on how to not get cancelled for people who express controversial views on sensitive issues. If you think you might one day face a cancellation attempt, this piece may provide practical guidance. And if that’s unlikely, you can at least be entertained by my personal experience and get my thoughts on the history of cancel culture and more recent developments. Four lessons in particular stand out.

The Great Bifurcation

People often ask whether wokeness has peaked or not. I think what you’re seeing is a great bifurcation, with things being much better on the right, and generally the same or worse on the left, namely in the mainstream media and especially academia. Most other institutions, including corporate America, are generally trending in a positive direction, due to Elon Musk buying twitter and conservatives starting to focus more on cultural issues from a legal and institutional perspective.

The way people use the phrase “cancel culture” is to a large extent outdated. We’ve inherited the term from an era in which there was more of a monoculture that is now in the process of ceasing to exist.

On the right, you used to have National Review as sort of the gatekeeper of intellectual conservatism up until around the early 2010s. If they thought you were “racist” or “sexist,” your ability to make a living or be taken seriously as a conservative intellectual or activist was extremely limited. And they to a large extent took their cues from the prestige media. Around 15 years ago, I would read the writings of those who were “purged” from mainstream conservatism like Peter Brimelow, Joe Sobran, and Paul Gottfried, and the extreme bitterness felt towards William F. Buckley and National Review was palpable. By 2010 or so, I don’t think it was that the magazine was itself as powerful as right-wing critics thought, but its name served as a kind of metonymic device for non-mainstream thinkers to rally against, representing the idea that there was only a handful of powerful conservative gatekeepers that either granted or denied legitimacy.

Today, there are many more media options, and in the marketplace of ideas (or “ideas”) the anti-woke side has been winning out. Even without any official affiliations or the help of any mainstream conservative media outlets, a compelling writer or activist can go to X or Substack and make a living. Politicians, donors, and other conservative elites have responded to these dynamics, with establishment institutions moving towards wherever the populist energy happens to be. The right now sees part of its core identity as not caring what the mainstream media thinks, and not taking cues from them, especially on identity related issues.

The result has been that it’s really hard to get cancelled as a conservative these days, at least for “racism” or “sexism.” Paul Gottfried was one of those cancelled in a previous generation for, according to his account, not loving Martin Luther King, Jr. enough and opposing neo-con wars. Last year he wrote in The American Mind on how the stranglehold of the old gatekeepers has been broken, and I think he’s clearly correct.

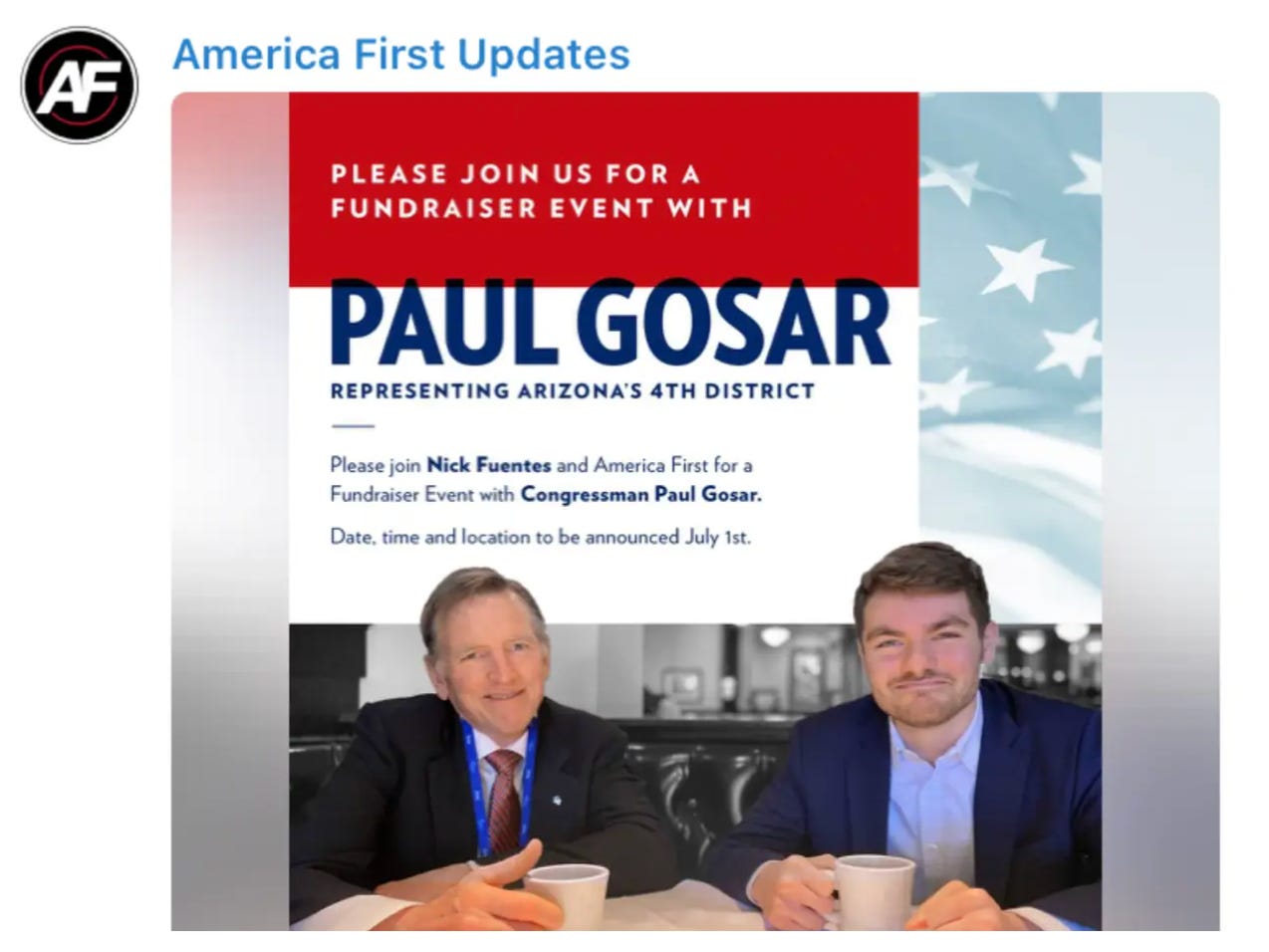

My favorite piece of anecdata is represented in the picture below. If you’re not convinced by my arguments, just check out who members of Congress are hanging out with these days.

Nick Fuentes isn’t getting meetings with Mitch McConnell, but the fact that a guy like this has a role to play in the conservative ecosystem at all tells you something. Charlie Kirk at first found himself under attack by Fuentes and his “groyper army,” and that only ended when Kirk moved towards them on race and identity issues. Even people on the right who dislike individuals like Fuentes dislike the idea of denouncing him even more. If Mitch McConnell and Tim Scott aren’t palling around with Fuentes like Paul Gosar is, it’s more because they’re genuinely disgusted with his views rather than afraid of what CNN thinks.

To be “racist” and “sexist” can even be an advantage, depending on how tied to institutions you are. John Ganz, one of those liberal essayists whose obsession with me makes me feel very important, is actually perceptive when writing about his experience infiltrating the world of young conservative journalists and activists.

The other thing I saw is that they related to the extreme fringe as some kind of oracle of forbidden knowledge. They were like these chtonic forces that had to be listened to for some reason. They would show me things and I was like, “These people are just obviously mentally disturbed shitposters,” but to them it contained some deep wisdom. And often, the more deranged, the better: it was closer to The Real for them.

This in part helps to explain the BAP cult. His extremism is actually an advantage in appealing to young conservatives. This is not alway good, as I sometimes feel like many of them are just seeking out the most extreme or provocative figures they can find on identity issues and then adopting whatever economic or social views they happen to hold. But whatever this is, it certainly isn’t cancel culture.

Meanwhile, on university campuses, we’ve seen the institutionalization of woke. I don’t think it’s even a matter of the official rules and regulations any more in the form of things like DEI statements. The environment has become so stifling over the last decade that it has pushed out a lot of people with centrist or conservative views. I think those left behind want, or at least are comfortable in, a woke monoculture. I’ve been reading BAP’s dissertation, and it’s funny to think how we were in academia at around the same time and what each of our trajectories would have looked like if the environment was different enough that we could’ve stayed. I think we’re clearly both doing much more good on the outside, so the fact that academia has gone in such a terrible direction isn’t all bad.

Cancel culture remains strong on university campuses even though we don’t see much physical intimidation and violence on the part of student protesters like we did in the mid-2010s. That kind of revolutionary fervor tends to always burn itself out. In many cases the protestors got what they wanted, while in others administrators have stood for free speech, but it doesn’t matter all that much because everyone who doesn’t buy into left-wing ideology has already decided to go into another profession.

This generation doesn’t have an Arthur Jensen – anyone that interested in truth on racial issues is weeded out long before they become a tenured professor. It’s hard to imagine that in the early 1990s there were prominent psychologists at both Berkeley and Harvard who publicly argued for the plausibility or likelihood of the black-white IQ gap being genetic. Today, even if a university adopted a pro-free speech policy, such professors would have to deal with open and never-ending hostility from college staff, students, and colleagues. The administrators at their schools wouldn’t necessarily ban them from speaking, but they would face ethics investigations, be shunned by their colleagues, see all their grant money dry up, and have the entire machinery of the university turned against them. No policy change can, for example, force graduate students to work under a politically incorrect professor if they think doing so is bad for their careers, or they’re genuinely horrified by his views. We’re at the point where wokeness at universities is more a matter of culture than anything that outside forces or policymakers can fix, although it’s definitely still worth taking steps like shutting down the activism masquerading as scholarship in the various “studies” departments.

The media, meanwhile, is as biased as ever on sensitive issues. Even though there’s been some sanity on trans, the Great Awokening and BLM have created a stranglehold on anything related to black people. Thirty years ago, The Bell Curve could get a sympathetic review in The New York Times, while today I’d don’t think you could even publish the Freakonomics argument about black naming patterns and crime in a major newspaper. I remember reading about it at the time in mainstream publications who treated it like a normal social science finding, which would be impossible today. Outside of conservative publications, white people basically can’t talk about black people at all except in the language of left-wing activism.

What all of this means is that the first step to not getting cancelled is to understand the great bifurcation, and if you can, avoid making academia or journalism your career. I’ve always known that I wanted to be able to tell the truth, and there were things in my past that could come out, so I built my public profile with that in mind. There has never been a better time for an independent thinker to push the envelope on sensitive issues if they’re inclined to do so. I don’t think that the fall of right-wing gatekeeping has been an unalloyed good, as it’s why conservatism is now so full of grifters and cranks. At the same time, it has unquestionably led to the opportunity for more truth telling when it’s needed.

Don’t act cancelled

I’ve known others who have been the victims of cancellation attempts, or observed their situations from afar, and very often they seem to take a passive posture and see themselves as observers of the process. They’ll dwell on how cancelled they are and how hard their lives have become, which I think becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

But you don’t have to be resigned to your fate. When the Huffington Post story was published, I was on my one real vacation of the year for the entire week. The author first tried to make contact on Wednesday, August 2nd. He left a voicemail, and then sent a DM explaining to me what was going on, saying his deadline to receive a response was the next day. I decided there was probably no benefit to talking to him, and so Thursday I went to Seaworld, and waited for the piece to drop. I received a stream of emails and texts throughout the day from people who had been contacted about the coming story.