Organized Labor Requires Government Coercion

There is no argument for unions from the perspective of negative rights

Note: This is the first article in a three-part series on the problems with organized labor. To read the second, as to why organized labor contradicts basic economic principles and make society worse off, see here.

When I started writing about the problems with civil rights law, few people had any idea what I was talking about, even in right-wing circles. Most understood the Civil Rights Act as the bill that got rid of Jim Crow and banned explicit discrimination. It did in fact do those things, but as I argue in The Origins of Woke, civil rights law has over the years expanded to mandate differential treatment based on race and sex, and institutionalize concepts like affirmative action and disparate impact.

It seems that I’ve succeeded in changing the conversation around these issues. Now, conservatives know that the whole thing is a con and understand that when someone is a “civil rights advocate” they’re not simply demanding equal treatment for women and minorities, but in favor of policies that lower standards, restrict freedom, and discriminate against whites, men, and Asians. “Diversity” and “DEI” have similarly become politicized terms.

I feel like the conversation around unions within many intellectual spaces is about where the civil rights discourse started. I’ve heard people defend organized labor on freedom of association grounds. Why can’t workers get together and engage in collective bargaining with their employers? Don’t they have a right to do so? This lack of understanding has coincided with people on the right starting to say nice things about labor unions, including JD Vance, Josh Hawley, and the intellectuals around American Compass. It may be that conservatives who have taken on organized labor in the last decades have been too successful, to the point that young people on the right don’t even know what unions are anymore.

For this reason, I’ve decided to write a three-part series on collective bargaining. In this first essay, the goal is to just lay out the facts about unions and explain why they are products of government coercion. Part II will make the case that even if you don’t find pro-freedom arguments compelling, no matter what your value system is, unless it is highly unusual, you should not support labor unions. Relying on basic economic concepts and ethical considerations, I explain why there are more effective and just ways to deal with problems like inequality and asymmetric bargaining positions between firms and workers. Finally, Part III will argue that this is a fundamentally important issue, and one of the main reasons that the United States is so wealthy is that its laws don’t create special rights for unions to the same extent that those of other developed countries do. This means that maintaining American dynamism depends on making sure labor unions don’t regain the power they had in the mid-twentieth century.

Unions Restrict Freedom of Association and Other Rights

Pro-freedom arguments for labor unions that hold to a negative conception of rights tend to completely misunderstand what labor law actually does. Imagine that a group of customers of a store decided that they weren’t going to shop there until it reduced its prices. A boycott like this is of course legal, and there is no ethical issue. Now imagine that government requires that the store negotiate with this group, on everything from the products it carries to what hours it opens, and the result of those negotiations determines under which conditions all customers, including those who have no relationship with the organization, can shop at the store and what they can buy. If no deal is reached, it may lead to a shutdown of the store. Moreover, the business can’t ahead of time decide it doesn’t want such customers in the first place nor try to discourage those who enter from forming a consumers union.

It doesn’t matter if there are other stores that the gang can go to, and it doesn’t matter if the business and other customers want nothing to do with them. In the eyes of the law, they “represent” consumers, and so get to decide the terms on which other people can transact with one another.

This is not a strawman. This is exactly how private sector labor unions work. In 1935, President Roosevelt signed the National Labor Relations Act, which is sometimes called the Wagner Act. As explained in a book on the current state of labor law,

The majority of workers in an appropriate bargaining unit decide whether or not all the workers in that unit will be represented by a union. If a majority of workers in a bargaining unit choose to be represented by a union, the employer must bargain with the union regarding all the workers, even those who would prefer to bargain individually with their employer. The union becomes the exclusive bargaining agent of the unit; the employer must bargain with this union and none other. But if the majority chooses not to be represented by a union, the employer need not bargain with the union, even though many workers might be members of it.

Employers must not stand in the way of union organizing, and there are intricate rules that have developed over the years regarding what this means in practice.

At every step of the way, unions restrict freedom for different parties

The employer cannot decide whom to hire and fire at his own business.

The minority of workers who do not wish to join a union get the “benefits” of whatever the union decides, which means they are not free to have different arrangements they believe are best for themselves.

New employees cannot take a job with an employer at a business if it is unionized and they do not want to work under conditions that the union doesn’t approve of. Whether they can take a job with the employer at all might depend on if they live in a right-to-work state (see below).

Consumers are not allowed to have the kind of relationships they want with a business like, for example, buying cheaper products that are made with laxer safety standards. This is the case even if the firm wants to provide them with the goods or services they desire, and they can find someone else willing to do the work.

Most states have passed right-to-work laws, which usually say that unions can’t reach agreements with employers requiring that everyone at a job belong to the union. It has been argued that this violates the principle of freedom of association by prohibiting a certain type of contract. But this ignores the larger context of the Wagner Act, which requires collective bargaining when the majority of employees at a business vote to form a union. Given that this restricts the freedom of association rights of employers, consumers, and employees who don’t belong to the union, what right-to-work laws do is simply put limits on the degree of this coercion.

As with civil rights law, requiring “nondiscrimination” extends to restrictions on speech. Although an employer can close a business in order not to have to deal with a union, in NLRB v. Gissel Packing Co., Inc. (1969) the Supreme Court ruled that he can’t inform workers before the vote on forming one that this is the path he will take if doing so can be interpreted as a threat. In another analogy to civil rights law, courts have also abrogated for themselves the role of deciding whether certain kinds of firm behavior are permissible if they are motivated by animus towards unions. And although an employer can close down a business because he doesn’t like unions, his right to do so is limited if it can be interpreted as trying to influence employees in another part of the company. Unions’ hostility to speech can be seen in the United Auto Workers having just filed a complaint against Donald Trump and Elon Musk for talking about their opposition to organized labor during their conversation on X this week. Just as how some legal scholars argued that Google needed to fire James Damore in order to create a non-discriminatory environment, labor law in many cases doesn’t allow business owners to have the wrong opinion on unions.

The point here is that once you’re committed to the non-discrimination principle, a lot of other rights go out the window. Since to discriminate is simply to prefer one person over another, and it’s often hard to know what motivates an individual’s behavior, what ends up happening is that rights like freedom of speech and freedom of association get curtailed. This is true whether government is forcing non-discrimination according to an immutable trait like race, or membership in a group one opts into like a labor union. One may argue that the latter case is particularly corrosive to individual rights, since a person is forced to associate with a kind of institution he wants nothing to do with and there is much more societal consensus around the idea that racial discrimination is wrong. Unions are often explicitly political and engage in activities well outside their core mission, which means being forced to associate with them can in effect require an individual to support political causes that he doesn’t believe in.

Labor law tends to also create special rights for union organizers who aren’t themselves employees. In 2021, the Supreme Court ruled that a farm can exclude labor recruiters from their own property, despite a California law saying that they were entitled to being there for three hours a day for 120 days a year. The fact that this even was a legal question, that is, whether a person has a right to go on private property and stir up trouble for its owner, shows the extent to which labor law tends to be hostile to individual rights. The growers who filed the lawsuit had lost in the Ninth Circuit before prevailing in the Supreme Court in a 6-3 decision that split along conservative-liberal lines.

The Wagner Act also allows federal employees to create unions. For state and local employees, public sector unions are governed by state law, with some jurisdictions allowing collective bargaining among government workers and others prohibiting it. Here, the concern is not so much freedom of association, as it is sort of weird to talk about freedom of association as a right of governments. Rather, the argument against public sector unions must be more purely empirical, and rest on the idea that the point of government is to seek the well-being of all citizens, not facilitate cartels to give certain groups special advantages at the expense of the rest of society. Public sector unions are of course worse and even less justified than private sector ones, but I will save the discussion as to why for the next two essays.

Are Free Market Unions Possible?

One might argue that while labor unions in the US are creations of government policy and restrict the freedom of others, this doesn’t have to be the case. Perhaps it is possible that workers get together, and decide to collectively bargain for their rights without any coercion involved. From a pro-liberty perspective, there is nothing wrong with this.

While that argument is correct in theory, in the real world, without the right to restrict the freedom of others, unions tend to be small and weak. This is because they run into a collective action problem. Imagine all of the employees at a coffee shop decide to form a union. The problem here is that without something like the Wagner Act, they can just be fired and replaced with other workers, and firms may simply refuse to hire or retain pro-union employees in the first place. Unions call those who cross the picket line “scabs,” as if workers have a moral obligation to not take jobs that people want to hire them for in order to help someone who wants to do the same work under more favorable conditions. To return to the consumers union analogy, imagine if the law made it easier for someone to stop you from paying $2 for a candy bar because they believe they have the right to buy it for $1.50 just because they started shopping at the store first.

One problem with the case for collective bargaining is that it overestimates the degree to which workers have the same interests. Humans vary a lot. Some people prefer work that is more strenuous but higher pay, while others would rather have a more relaxed job with lower compensation. Some really prioritize getting nights and weekends off, and others are at a point in their life when they are trying to save up for something important and would like to work as many hours as possible. Unions seek to represent all workers within a single establishment or job category and impose a one-size-fits-all agreement regarding what a job entails. Most importantly, workers vary in how competent and valuable to a business they are. Unions tend to reward the least productive workers by making them more difficult to fire and ensuring that pay and promotions are based on seniority rather than merit. Where there is freedom not to be part of a labor union, the firms that are not unionized will likely get the best workers and run the most efficient businesses, outcompeting those that rely on organized labor.

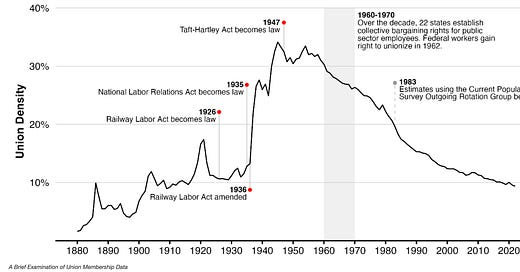

All of this is why union membership only took off in the twentieth century when governments began making collective bargaining mandatory, and then declined as the sectors and businesses that were unionized tended to see much lower job growth. There might be a few circumstances under which free market unions can exist and flourish. For example, imagine a small group of workers with a very specific skillset that employers in a certain industry rely on. But situations like this are rare. Below is a chart showing union density between 1880 and 2022.

One can clearly see the dramatic impact of the Wagner Act. The figure above actually exaggerates the influence of unions before 1935, as many more Americans used to work as farmers. So 10% of nonfarm employees belonging to a union in 1900, when around 40% of employed Americans worked on farms, is different from the same statistic in 2020, when around 2% do. As a percentage of the workforce, unions have a larger role in society today than they did in the early twentieth century.

In 1799 and 1800, the British government actually banned labor unions through what are called the Combination Acts. This was reversed in the Trade Union Act 1871. But for unions to take off, it required that they not be subject to broadly applicable criminal and civil laws. In the Taff Vale case (1901), a group of railroad workers in the UK went on strike. When the company hired replacements, the unionized workers began to sabotage the functioning of the rail lines. The House of Lords ruled that unions were financially liable for the damage that they caused while striking. This led to outrage and the growth of the Labour Party, which soon gained seats in parliament and helped overrule Taff Vale in 1906. The idea that unions would be responsible for the damage that they caused, like any other saboteur or individual who attacks private property, was seen as an existential threat to them.

Even before the protection of the Wagner Act, unions in the US likewise got their way through violence and extortion. They would take over a mine or rail line, and either seek to be paid off or dare the authorities to come in and stop them. Crucially, labor disputes generally did not involve a group of employees threatening to stop working and simply daring the bosses to get on without them. They have always had to prevent other people from doing the jobs they claim to have a right to, whether through law or extrajudicial intimidation and violence. This is why there has been such a strong connection historically between unions and organized crime, since both kinds of organizations rely on implicit and explicit coercion against honest people trying to make a living on behalf of the ingroup.

No Libertarian Case for Labor Unions

Current debates regarding labor unions aren’t about whether we should pass laws like the Combination Acts. Rather, the question is the degree to which unions should get special privileges. Everyone with an opinion on this issue should realize that if you leave things to the market and enforce broadly applicable laws against violence and property damage, there will be very few labor unions and the ones that do exist will be weak. Only through creating special laws for them that force collective bargaining onto employers, and not holding them to the same legal standards as other individuals and institutions, can labor unions flourish.

Of course, not all people are libertarians. Many care about inequality, asymmetric bargaining power between workers and employers, or have a host of other concerns. Some don’t take worries about individual liberty seriously when it comes to relationships with major power disparities.

I will address these arguments soon enough, and make the case that no matter what your values are, you should not support labor unions. I do not require that anyone adopt libertarian ethics to agree with me on the issue of organized labor. For now, it is important to clarify the terms of the debate. If you believe in strong labor unions, it in effect means you want to use government to restrict a wide range of agreements people are prone to enter into as workers, employers, and consumers. This is for the sake of facilitating one particular kind of agreement that is the result of forced negotiations between a firm and a group representing the majority of its current employees.

This may be worth doing in the end. But in no way can it be reconciled with common understandings of individual liberty.

I have very similar feelings about Unions. In arguing against them I often think about their historical contingency. Like if you were starting today, without the history of unions would these be the best tools for equalizing the power of labor vs capital. The answer is almost certainly no.

So I think we need to offer a trade. No unions, but a few programs that help labor be more powerful. We get no fault unemployment insurance. you can quit your job and based on how much time you've worked you get unemployment. Second the governement will pay for you to move, up to 3 times as long as it's to a place with more opportunity. Third sometype of systemization of retirement and health benefits accross all employers. You set up your 401k, and just give you employer an account number like direct deposit, health has to be similar, no changes with jobs.

If just say unions are immoral, which they are, but don't deal with the power imbalance, rational folks will stick with the unions.

A rare miss from Richard here but a large one.

At macro level you just won’t find any theoretical or empirical support for unions making a big difference to living standards.

I work in a large organisation in Europe and I’d say about 2/3 of my colleagues are union members. Non-membership is not a big deal, and membership is a trivial 0.5% of salary. I’m a member and I don’t have any interest in picketing or striking nor does anyone but a small minority. I am interested in my own working conditions, however, which align pretty closely with the 95% of colleagues who like me will never be senior managers. Membership gives me an outlet to push for utterly tedious things like parking spaces and work-from-home rights, etc. I keep union leadership appraised of my gripes, which get an outsize weight as most union members don’t bother to complain. I’ve in the past volunteered on union committees - again tedious work but one that gave me an insight into how the organisation works in a way that has helped my career progression.

If there wasn’t a union someone would in fact invent one or something very similar like an elected workers’ council. Management likes having a union there (at least in theory) as they can at least claim they have consulted on matters.

Overall Richard just overstates the impact of unions. They’re just another NGO and have a pretty minimal impact on the world.