Note: This is the second in a three-part series on the problems with organized labor. To read the first, on why labor unions are the result of government coercion, see here.

If you’re a libertarian, the fact that labor unions abrogate freedom of association and other individual rights might be enough reason to oppose them. But most people are willing to sacrifice some level of economic freedom to help the poor or reduce inequality. In this essay, I’m going to explain why, if these are your concerns, organized labor is a particularly terrible way to achieve your goals. Regulations favoring unionization are not only bad for economic growth, but not particularly targeted at providing help to those who need it most.

Two Types of Government Regulation

Broadly speaking, one can put government interventions to address poverty or inequality into two categories. First, there is direct redistribution. Government simply takes money from one group and gives it to another. Classic welfare programs fit into this category, as do things like unemployment benefits and the child tax credit. Second, there are attempts to interfere directly in the market. Instead of letting businesses and individuals do what they want and using the tax system to redistribute wealth, governments may try to not let income and wealth gaps get so large in the first place by regulating the behavior of individuals and firms. Policies in this category include price controls and price floors, licensing requirements, limits on working hours, and, of course, mandatory bargaining with labor unions.

One can disagree on the extent to which government should try to help the poor or reduce inequality. But no matter where you come down on this question, direct redistribution is preferable to interfering with the market. This is because interference in market processes tend to lead to larger inefficiencies. The thing about taxing money and redistributing it is that, if a market transaction is welfare enhancing enough, it will still get done. But if you ban a certain kind of transaction, there is potentially no upper limit to how much economic damage you might cause. Take the example of whether to allow Uber to operate within a jurisdiction. It doesn’t matter how useful people might find the service or what they would be willing to pay; if government decides to ban the app, there is nothing one can do. If there are specific harms of Uber worth worrying about, like traffic congestion, government could apply a tax on the service, though there’s no reason why this shouldn’t take the form of congestion pricing that applies to all drivers.

The policies with the worst costs for the economy tend to be prohibitions, not taxes. For example, the 1920 Jones Act requires that cargo sent between US ports be on ships owned, built, and manned by Americans. It doesn’t matter if Canadian or Chinese operators could provide a superior service at a better price. The Jones Act is meant to help American industry, but our ship building capacity has atrophied anyway, as the US has come to move around a remarkably low percentage of its freight by sea. American workers could potentially benefit from foreign ownership of vessels, and American businesses might be able to do better if they could employ foreign workers, but such transactions aren’t allowed. Overall, the Jones Act is estimated to cost tens of billions of dollars a year, but no matter how high the costs get, the economy can’t adjust to take advantage of the savings or superior service that foreign ship makers and workers can provide.

Even more significantly, when economists try to estimate the costs of housing regulations, they come up with massive estimates. Zoning laws make building more expensive, and also directly ban many kinds of dwellings from being constructed in the first place. This is particularly harmful, because no matter how massive the potential gains, nothing can be done to meet an intense housing shortage.

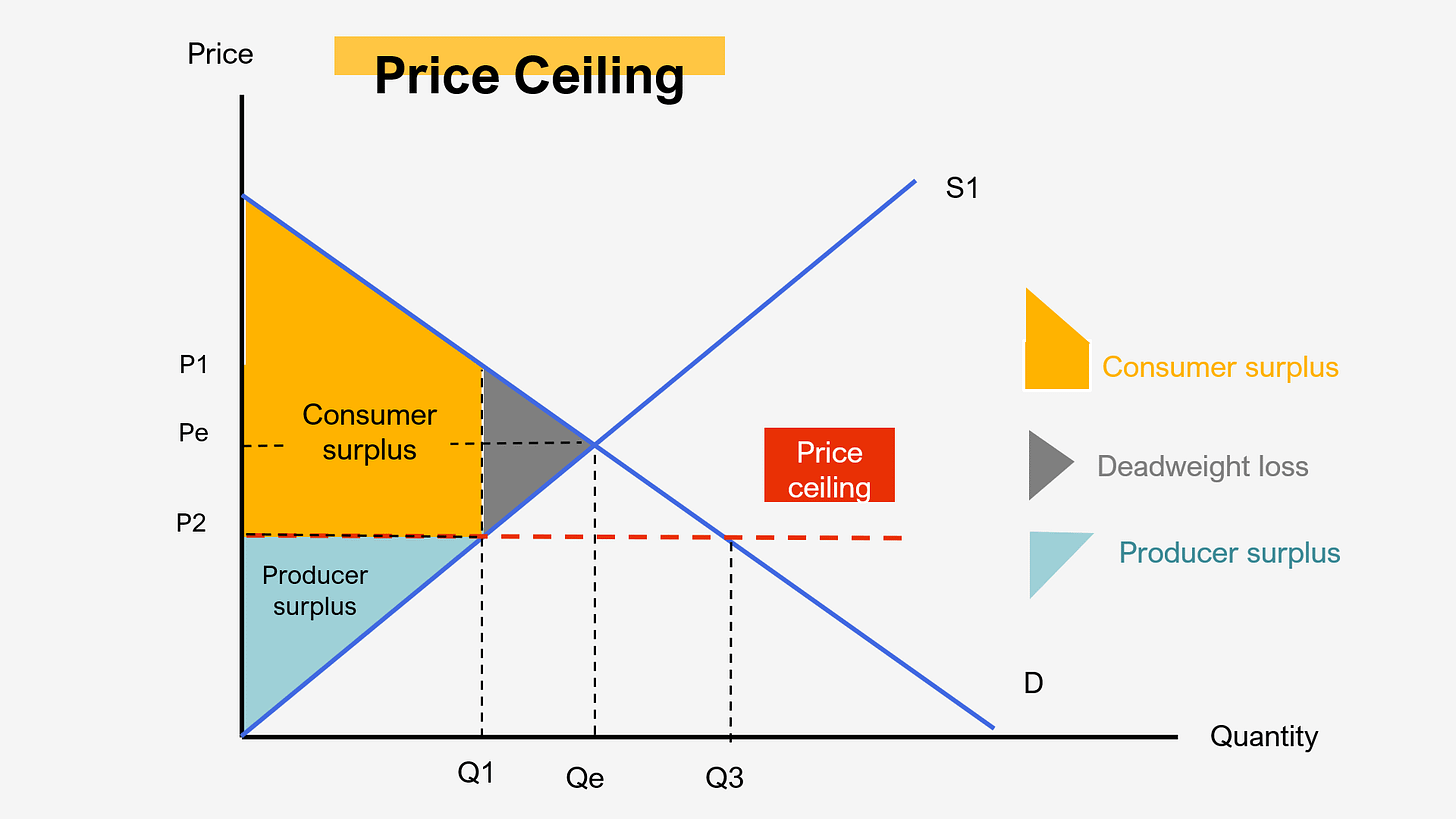

Economists use the term “deadweight loss” to refer to market transactions that do not occur due to government intervention. The two graphs below demonstrate the principle, showing what happens when government introduces price controls.

The goal is to maximize surplus. So when there is an unregulated market, price reaches Pe, where supply meets demand. Now imagine government sets the price at P2. Some consumers certainly gain, because they were able to get the same product for a lower price. The problem, however, is that sellers not only make less profit, but bring less of the product to market. This means that other consumers are not able to buy something they would be willing to pay for at the market price. The gray area in the second chart represents deadweight loss, which can be taken to represent how much poorer society becomes.

In this hypothetical, people can be nearly divided into the categories of “consumer” and “producer.” In real life, however, all producers are consumers too, since they need to buy things. If you set price controls across the economy, or enact other forms of flawed government regulation, we all get poorer. Another simplification in this example is that we assume the existence of a single homogenized product. In real life, technological and production innovations allow improvements in goods and services, and price controls limit the incentive to innovate by capping the ability to make as much profit as possible.

All of this is less of a problem when you just directly redistribute money. While the transaction costs of doing so might be considered a kind of deadweight loss, otherwise you’re just moving cash around. Of course, higher tax rates and welfare programs can discourage work too, and this is the efficiency versus equality tradeoff people always talk about. But if markets can remain relatively undisturbed and the laws of supply and demand are able to operate, we are generally better off. If you want something bad enough, you can get it, and innovation still moves forward.

Things are even worse than the figure on deadweight loss suggests, as it assumes that the consumers who are willing to pay the most for the good or service are still able to get it. In the real world, there is no reason to believe this is the case.

Let’s say many people are willing to pay $100 for a widget, but there is a shortage of widgets due to a price cap that doesn’t allow sellers to charge over $10. Since the fewer widgets that are produced can’t be distributed according to who is willing to pay the most for them, some other system has to be found, usually first-come first-serve. But this is a terrible way to distribute scarce goods and services, since the product in question is much more valuable to the person willing to pay more for it. If products that are subject to price controls are inputs into other products, one can imagine how much of a distortionary effect on the economy such policies will have.

In addition to creating less deadweight loss, the other benefit to direct redistribution is that you can be more confident that it addresses poverty and inequality. Do price controls actually benefit the poor? Maybe some poor people get to buy eggs or milk at a lower price. But if you artificially create a shortage, other poor people won’t be able to buy these products at all. Minimum wage laws might increase pay for some low skilled workers, but they will put others out of a job.

To go back to the Uber example, it makes no sense to care more about taxi drivers than other working-class people, including those who might not be able to afford a ride due to the taxi cartel jacking up prices and rideshare contractors not allowed to work. If members of a group happen to be poor, you can help them through the welfare state, but there is no reason to simply adopt a scattershot approach to every single industry where one is worried about workers, creating deadweight loss (i.e., making everyone poorer in the aggregate) all along the way.

A final point here is that up until now, I’ve been acting as if government can foresee the ultimate consequences of its actions. We usually don’t have enough data to forecast the impacts of complex economic regulations on different groups of people. Is raising the minimum wage worthwhile given the number of jobs that will never be created? Who exactly gets hardest hit by prohibiting Uber and making taxis more expensive? You could tell different stories, but the advantage of direct redistribution is that it requires a lot fewer assumptions. Find out who is rich, find out who is poor, and you’re basically done. That’s not a completely trivial task, but it’s a lot easier and simpler to do than making complex predictions about how millions of people will behave in response to any particular intervention in the economy.

History backs up the idea that redistribution is better than trying to micromanage millions of individual decisions. The Nordic social democracies are wealthy, while countries like Venezuela, Argentina, and those in the former Eastern bloc have sought to more directly manage the economy. Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Denmark actually do quite well in indexes of economic freedom because even though they tax and spend a lot, they to a large extent otherwise leave the economy alone. I tend to think it’s pretty absurd to put these countries ahead of the US in terms of economic freedom, as these rankings often do, and I’ll get to that in the next essay, but it’s unquestionably true that Nordic countries today don’t have many of the kinds of leftist economic policies we often see in the third world. If you look at the worst performing countries since the 1950s, it’s basically a list of nations that have had civil wars plus Argentina and Venezuela.

I’d argue that Nordic countries are still much poorer than they need to be because they create too many disincentives to work hard and innovate, but still, they haven’t been complete economic basketcases.

Deadweight Loss, Preventing Innovation, and Regulatory Burden

It’s obvious by now where I’m going with all of this. Laws protecting unions are clearly the bad kind of regulation. They are prohibitions on individuals doing non-unionized work, or refusing to negotiate with a party that might be incompetent, selfish, or acting in bad faith. Labor is simply another kind of input into the economy, and when you set wages or working conditions artificially high, you once again get deadweight loss, as demonstrated in the figure below. Of course, everything I said above about figures like this underestimating the negative effects of price controls also applies here.

Leftists will sometimes favor price ceilings when it comes to goods being sold, and price floors when it comes to wages. In the first case, they see themselves taking the side of consumers over business, and in the second, workers over business. Yet both policies make society poorer overall, because they lead to fewer jobs being created, and fewer goods and services provided.

Moreover, unions don’t necessarily help the least skilled or worst off people in society. By raising the price of labor, they make it less rational to hire less skilled workers. And they may often harm consumers who are no wealthier than the union members themselves, when they raise prices or force businesses to close down.

Another concern in regulating the economy is that you always want to create fewer, rather than more, transaction costs. If an economic intervention increases GDP by X but costs > X to implement, this is an argument against the policy. The American tax system is extremely complicated and requires a lot of paperwork. This is in part thanks to lobbies like TurboTax, which benefit from the status quo. If government could simply pay them more than the business is worth to go away, everyone would probably be better off, but there’s no way to facilitate such a deal. Special interests will often have no problem harming society in order to gain something for themselves, even if what they gain is worth less than what the rest of us lose.

Laws protecting organized labor create artificial bureaucracies when none need to exist. This provides opportunities for corruption, and potential principal-agent problems. Sometimes bureaucracies are necessary; it would be hard to imagine police work or a functioning tax system without them. But in situations where they are not, we should be reluctant to create them.

Labor unions advocate wealth destroying policies even when they’re not acting in a way that is directly antagonistic to their employers. For example, hotel unions oppose Airbnb, putting them on the same side as their bosses. Many unions support protectionism for similar reasons, benefiting themselves and the firm they work for while hurting society as a whole. This kind of activism can be seen as demonstrating the general principle that when government creates cartels whose goal is to maximize the well-being of its own members, there are bound to be all kinds of perverse consequences.

One example of the damage labor unions tend to cause can be seen in their fight against the mechanization of ports on the West Coast. Scott Lincicome has written about this, as in the passage below.

As we’ve discussed repeatedly, labor disputes at U.S. ports occur somewhat regularly (basically every five years or so when the current contract is up), especially out West, and have recently centered on the issue of automation: Port operators and ocean carriers want to use robots, autonomous vehicles, drones, and other cool tech to boost container processing efficiency (“throughput”), while port unions strongly oppose this “job-killing” modernization. And, because the ILWU represents basically all dockworkers on the entire U.S. West Coast (22,000 of them at last count), because those ports are so critical to U.S. trade (especially imports from and exports to Asia), and because both labor law and California politics heavily favor the union, the ILWU been extremely successful in blocking technology that’s widely used around the world (even in places like Europe with strong labor unions)…

Most obviously, research consistently shows that work slowdowns and stoppages act as a self-imposed blockade on imports and exports from the ports involved, hurting anyone — workers, companies, farmers, transporters, etc. — linked to those transactions and the U.S. economy more broadly. Thus, for example, the Congressional Budget Office in 2006 calculated that just the direct costs of an unexpected 7‑day strike at Los Angeles/Long Beach would run between $65 million and $150 million per day. A 2008 paper, meanwhile, found that the 2002 West Coast port strike, which resulted in a 10-day lockout, “cost the U.S. economy billions of dollars,” created a 100-day backlog of ships waiting offshore, and depressed the stock prices of affected U.S. companies by approximately 8 percent on average. And a 2018 study found that just the work slowdowns in 2014–15, which the ILWU (of course) denied, significantly dented port efficiency for several months and thus generated more than $7 billion in direct economic losses and another $3–5 billion in indirect ones. (All values are in current dollars, so the losses would be much bigger if I weren’t lazy and did the inflation adjustment for you.)

What I find particularly maddening about this is just how much damage can be done in the interests of such a small group. The article mentions that there are only 22,000 dockworkers on the West Coast. That’s out of a US civilian workforce of 168 million. West Coast dockworkers are 0.01% of all workers, and able to hold the other 99.9%+ of the country hostage. You could probably pay all the dockworkers hundreds of thousands of dollars to go away and it would still be worth it to modernize American ports. Thanks to a lack of automation, we have some of the least efficient ports in the world.

Orthodox economic theory recognizes that cartels are particularly bad because they restrain transactions that would otherwise happen simply to benefit a select few. The debate over antitrust law has always been what and how much government should do to stop them from forming. I’m not a big fan of antitrust law, agreeing with Joseph Schumpeter’s critique of the concept in Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. Yet in the debate over organized labor, the question isn’t whether government should prevent cartels, but whether it should create them.

The cornerstone of antitrust law in the United States is the Sherman Act of 1890. In early court cases, judges ruled that unions organizing boycotts and strikes was illegal, because it involved a restraint of commerce or trade, which Congress had outlawed. Just as how two businesses could not conspire to set an artificially high price for their product, groups of workers could not do the same when selling their labor. Congress eventually decided in the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 that labor was a special case and exempt from the earlier law. As previously discussed, the Wagner Act two decades later not only allowed union cartels but in effect facilitated their creation across the economy.

Labor Unions and the Pareto Principle

Up to this point, I’ve mostly been treating labor unions as if they are simply a direct regulation, like the minimum wage. But this actually downplays how bad they are. Minimum wage laws and direct government regulations of workplaces have many of the same shortcomings of organized labor, but they tend to create less deadweight loss than unions.

One reason for this is that, as mentioned above, unions add layers of bureaucracy to society. When government sets a minimum wage, it simply decides on a rule everyone has to live by. It’s much worse to force an adversarial relationship onto workers and firms and create a private sector apparatus that mimics government, with all of its pathologies. Remember, it only takes a majority vote within one particular establishment to unionize. The other 49% of workers at the company might want nothing to do with organized labor, and they are prohibited from coming to a different agreement with their employer.

Even without unions, businesses have an interest in keeping their workers happy. This is why firms will often put together workers committees to address things like pay and working conditions in a non-adversarial setting. Organized labor tends to be hostile to these institutions, seeing them as rivals. The Wagner Act actually bans company unions for this reason.

Unions are also consistently anti-meritocracy. This isn’t a problem with other kinds of regulation of the economy, like minimum wage laws. If you have to pay $20 an hour to each employee because that’s what the government requires, you are sure to find the best worker you can for that price. Labor unions, however, practically always negotiate for a seniority system. This is true in the case of teachers unions fighting against education reform, even within the Democratic coalition during the Obama years, and also among private sector unions. This might appear confusing at first glance, as there doesn’t seem to be an immediate and obvious connection between collective bargaining and being anti-merit.

Yet it makes sense when you consider that unions have an ideological and material interest in building solidarity among workers, along with loyalty to the unions themselves. This is difficult to do if you acknowledge that some are much more productive than others. According to the Pareto Principle, a minority of workers tends to be responsible for the vast majority of productivity in any organization. This holds across industries and job types. Since unions need to win over a bare majority of workers in order to negotiate on behalf of everyone, including future workers at a plant or firm, what ends up happening is that the incompetent gang up on more productive employees and those seeking new opportunities. A hard worker is not going to be as in favor of a seniority system as someone who wants to simply do the bare minimum to get by; they would rather that employers have the option to compensate based on performance. Rules that make it difficult to fire employees likewise benefit the least productive, and stop them from being replaced by new hires who work harder or others currently in the firm who might be willing to do their share of the work for higher pay. The fact that unions tend to overwhelmingly attract and serve the interests of the lazy, unambitious, and incompetent has implications for the culture they create and how they end up negotiating with employers.

Unions create terrible incentives, and worker solidarity often shades over into hostility towards bosses, customers, and society as a whole. Skepticism towards the ideas of merit and getting ahead become embedded in the culture. After I published an essay on why unions are immoral last year, a reader wrote about his experience while growing up in the heyday of organized labor:

My father and several uncles and aunts were factory workers and union members…

To make money for high school and college, from the time I was 16 until I was 21, I worked every summer at The Lakeside Press, an enormous factory complex covering several blocks about three miles south of the Chicago Loop. We printed Sears catalogs and phone books for major cities, Time, Life, Sports Illustrated, and much more. I worked in the bindery, carrying stacks of printed paper to the binding machines, or loading or unloading conveyor belts. I once figured out that I was loading 81,000 lbs of catalogs per day onto the conveyor belt. I worked with some other students working their way through school, but mostly with full-time laborers…

The company sponsored a bowling league, a softball league, an annual picnic, and other activities, and published a beautifully bound, gilt-edged, book on some topic of American pioneer history every year. A book was sent as a Christmas gift to all full-time employees.

The company promoted from within and sponsored free classes for people who wanted to get ahead. If you got into an apprenticeship program, they paid you to attend class. There was a generous profit-sharing plan for people who came up with new procedures or mechanical innovations which saved the company money. A good idea was worth thousands of dollars per year for five years. Everyone kept their eyes open for ways to help themselves by helping the company.

The company did not provide all these employee benefits just to be nice. A major motivation was to keep the employees happy so the company would not become unionized.

Having no union made a tremendous difference. Employees were expected to keep their own work area clean, while janitors just cleaned the common areas. The management could put you on a different job whenever the need arose. There was no grief about needing to belong to a certain union before you could do a job. One day the machine I was working on had a major breakdown. About twenty people were suddenly idle. There was nothing for us to do, so the boss said, “You guys can check out and go home early, but I know that you need the money, so everyone who wants to stay come with me and you can start painting the walls of the warehouse.” There was no painters’ union to complain.

In all the time I worked there, I never heard anyone complain about the company. We workers felt that we were part of the company.

The summer between my two years of graduate school I got a job at The Riverside Press in Cambridge. I figured it was perfect: it was right down the street from my apartment, and I knew how to do the job. I even got to work the evening shift, which is what I’d done in Chicago. The Riverside Press was a union shop. The contrast with The Lakeside Press was astounding.

First, it paid about 7% less per hour. I attribute this to the employees being so unproductive that the company could not afford to pay them more. The place was filthy, but you were not allowed to sweep your own floor because that “took a job away from a member of the janitors’ union.” Machinery broke down more frequently because there was no pride in being productive. Every costly breakdown and idle hour was seen as a way to “stick it to The Man”.

One night the foreman asked me if I wanted to work overtime. Usually the plant closed down at eleven, but they were terribly behind on an order and were willing to pay time-and-a-half to catch up. I gladly said yes.

At eleven I went to the lunch room for some coffee and a quick snack. At about twelve after, I got up and started to leave. The operator of our binding machine said “Where in the hell are you goin’?”

“I’m going upstairs. Don’t we start at 11:15?”

“Sit down,” he ordered. “All the bosses go home at eleven. We work or asses off all day. They can’t make us do it now.”

I told him I’d be more comfortable waiting at the machine and left. At about 11:45 the first crew members started straggling in. The operator turned on the machine at twelve but ran it slower than normal. Fifteen minutes later he stopped it and turned off the working lights. “That’s it,” he announced.

We spent the next two hours and forty-five minutes sitting around so we could punch out at three…

Many articles about unions talk about their costliness and destruction of productivity. (An exhibitor at a computer convention was forced to pay $350 for a union electrician to make a service call to plug in an extension cord. A theater group had to pay an entire orchestra to sit silent each night because the only music required by the script had to be a local station playing on the radio. Enthusiastic new workers who point out ways to be more productive are told to slow down or face the consequences.) But I haven’t seen mention of the serious damage done by unions in their destruction of the human spirit. People in union jobs are constantly told by coworkers that they are being screwed, mistreated, and exploited. People are frustrated by being kept from doing their best. You can’t live with those feelings year after year – and spend every day bitching about it – without feeling terribly inadequate.

We might feel sorry for the lazy and incompetent, but the problem with letting them gang up on superior workers is that we all benefit from having a more meritocratic society. If you don’t want to blame individuals or see them suffer for being unproductive, then simply advocate a free market economy that unleashes the forces of meritocracy and supply and demand and then work to directly provide help to those who need it.

Are Unions Responsible for All Good Things?

One argument that supporters of unions make is that they have been responsible for improvements in pay and working conditions over the course of history. For example, see this meme that Bernie Sanders posted to Facebook in 2020.

In this telling of history, employers were once allowed to do whatever they wanted to those they hired, and only when working people organized were they able to coerce businesses into treating them better.

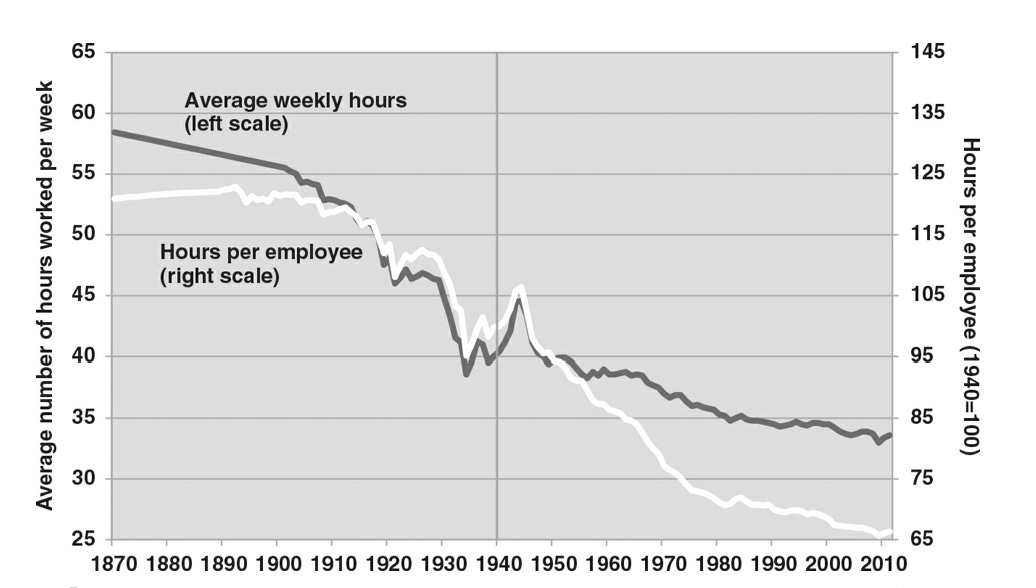

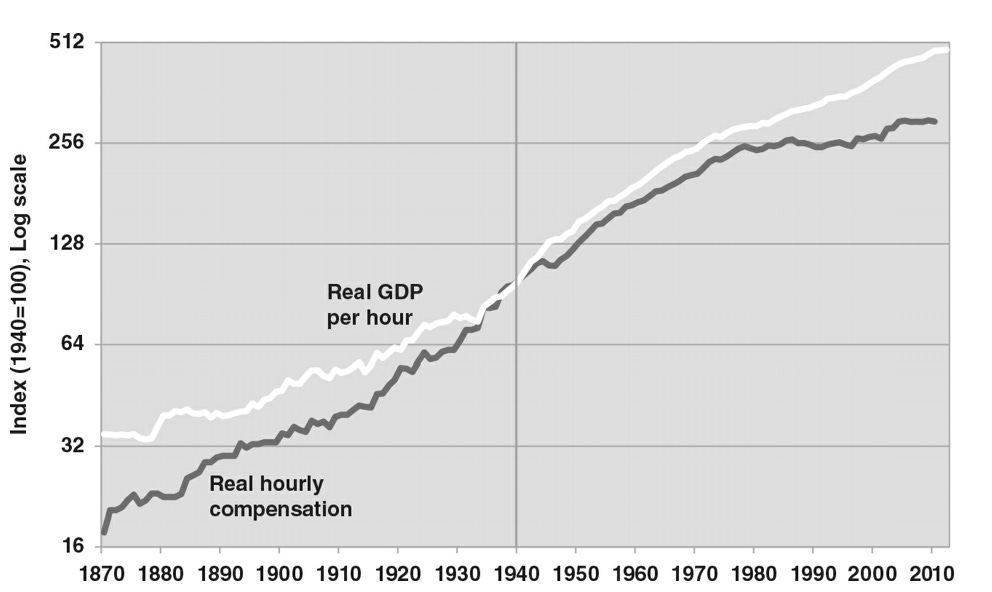

It is true that working conditions have improved over time. Yet one would expect this to happen anyway as societies get wealthier. If you look at improvements in working conditions across the decades, it’s difficult to see the effect of labor unions. Here’s one chart from Robert Gordon’s The Rise and Fall of American Growth.

As you can see, average number of hours per week declines pretty much continuously from 1870 until 2013, with the notable exception of a sharp increase during the Second World War. There’s nothing to indicate that the growing strength of labor unions in the middle of the twentieth century had anything to do with it. You see the same thing if you look at wages.

It’s not difficult to understand that people will accept lower pay, more dangerous conditions, and work longer hours when they are poorer. If unions hinder growth, then they may increase the well-being of workers in the short run while hurting them long term.

Imagine if someone said that without a customers union, stores would treat all their patrons poorly and charge them thousands of dollars for a loaf of bread. This doesn’t happen because stores are in competition with one another, and try to attract customers based on price, service, and the quality of goods. We have generally applicable laws against things like fraud and selling tainted meat, but there is no need for collective bargaining on behalf of consumers. If you don’t like a business, you find a new one, and if enough people feel the same way, it soon won’t be able to continue operating. All reasonable people would agree that even if some good things could come out of a customers union, the transaction costs of such institutions would be so high and it would add so much friction and bureaucracy to society it’s wouldn’t be worth it. A system where we all just decide where we want to shop is obviously superior.

This same principle holds when it comes to the labor market. To see how this can work, note that only 1% of workers earn the federal minimum wage. Sometimes this is because state minimum wages can be higher than the federal minimum, but five states have no minimum wage laws, and even there over 97% of workers make more than firms are required to pay them. Clearly, competition for employees ensures that firms can’t simply pay them pennies on the dollar. The same is true for working conditions. Whatever it is that employees value – breaks, safety, or anything else more specifically related to a particular job — firms need to attract workers who have the option of going elsewhere.

The idea that unions are responsible for a reduction in hours and other improvements in working conditions is so commonly repeated that one may think it is something of an economic consensus. But a 1995 survey of members of the Economic History Association shows that they overwhelmingly credited economic growth.

I don’t think we should rely on appeals to authority because experts can be biased, but at the time economists tilted towards the Democrats by about a 2:1 ratio. That number has grown in the years since, but even in the 1990s economists clearly weren’t knee-jerk free market fundamentalists on most issues.

Some pro-union types argue that it is the threat of unionization that keeps employers in line. There are studies that claim to demonstrate this empirically, with others showing the opposite effect. This is one of those questions not really suited to empirical analysis, as without experimental or quasi-experimental methods such work is hopelessly confounded, and there’s no way to measure all outcomes we might care about, like the society-wide effects of increasing unionization. To take one of many possibilities, if you have more unionization in an area, you might expect unions to attract many of the less competent workers for the reasons discussed above. This would mean non-unionized workers are more productive due to a selection effect, but a biased economist could argue that the same evidence shows unions raising the wages of all workers through a different mechanism.

Despite the impact of competition, it’s true that there can still be power asymmetries in the employer-employee relationship. Once again, and I’m going to sound like a broken record here, you may try to reduce those asymmetries by redistributing wealth. Someone who has a guaranteed income or free health care will likely be much less desperate for any job he can get.

People value different things. Even the rhetoric of the pro-union side assumes this away. Looking at the meme posted by Sanders above, we may ask whether the 8-hour work day is ideal. Maybe for some people, but certainly not others. Is child labor always bad? Definitely not, and if you tried to ban it in earlier centuries, it would’ve likely caused mass unrest, since putting kids to work was something of a necessity in societies where there were few white-collar jobs for adults, which means lower payoffs to education, and people were living in what we would today consider crushing poverty.

Critiques of the “gig economy” are similarly misguided. Some people like routine, while others want to avoid a commute and really value flexibility and convenience. The kinds of work that are available, what these jobs pay, and under what conditions individuals do them are ideally set by market needs and individual preferences, which, it must be said, government has no ability to weigh and measure. The pro-union movement tends to have a special hatred for more flexible kinds of jobs, because individuals who work at their own pace and at the times they prefer are difficult to organize, compared to those who all gather at set hours in the exact same place. But there is no reason to think that what is best for labor unions is in fact best for workers as a class.

A Word on Public Sector Unions

One piece of feedback I got on Part I of this series was that I should have talked more about public sector unions. I didn’t see this as necessary, as if you make a strong case against private sector unions, then it’s obvious why government unions would be even more problematic. I’ve seen people who support unions only in the private sector, but nobody who supports them only for government workers. Therefore, attacking unions unaffiliated with the state seems sufficient to make my points.

But, in case anyone needs to hear this, public sector unions are very bad. Government workers are ideally meant to serve the public. When they engage in collective bargaining, they have an incentive to get as much as they can out of government, and, unlike business leaders, political authorities usually don’t have much incentive to keep them from taking too much. It’s a particular problem when elected officials grant union members massive pensions, the costs of which won’t be felt until decades down the line. This is why the dominance of public sector unions is leading Illinois, along with the city government of Chicago, off a fiscal cliff.

Public sector unions also, not unlike their private sector counterparts, tend to get involved in politics, further tilting the playing field in their favor. Up until Janus v. AFSCME (2018), 22 states and Washington DC forced public employees who were not union members to pay “agency fees” to the union. In that case, the Supreme Court ruled this was unconstitutional, as individuals were forced to financially support a political organization as a condition of working for the government. Public sector unions negotiate directly with the officials who are their bosses, but there’s an extra layer of corruption when they provide funds to support the politicians they expect to give them more of what they want.

Ideological capture also tends to be a problem. During covid, the US was an outlier in terms of masking and school closures. Teachers unions were the primary reason for this. In Los Angeles, public schools did not fully open until April 2021, and mask mandates went on for a year longer. This shows the role of ideology in public sector unions, which are bad enough when they’re self-interested, but worse when they become culture warriors.

It looks like that due to covid extremism and their embrace of identity politics, teachers unions supercharged the school choice movement, harming their own interests. But ideological capture is a common occurrence in the world of organized labor, and the problem can be particularly bad in the public sector, where jobs are guaranteed and there is no competition. Any private sector union that behaved like teachers unions did in the last few years and acted this contrary to the wishes of those they served would have driven the business they work for into the ground. Teachers unions are suffering the consequences of their actions through declining enrollment and red states passing universal school choice, but the damage is much more limited and takes longer to manifest compared to what would happen in a competitive marketplace. In states and localities that are solidly blue, there have been almost no consequences at all.

Speaking of covid, as of two months ago, only 6% of federal employees were back to working in the office full time. The Biden administration asked them to return to work, but they refused, with one union representative saying that government workers are heroes and they don't have to be there if they don't want to. They sometimes show up to the office just to protest against having to show up at the office. Under some circumstances, working from home makes sense, and it’s hard to measure government productivity so who knows how much this matters, but the point is that the White House seems nearly powerless to have the kind of workforce it believes it needs to govern the country. Just like the teachers unions, the American Federation of Government Employees has milked covid for all it can. Note also that only 0.5% of the federal workforce gets fired every year, compared to 3% in the private sector, once again demonstrating the point that unions overwhelmingly protect the lazy and unproductive.

Public sector unions are, like their counterparts in the private sector, anti-meritocratic cartels that harm the rest of society. But being directly tied to government monopolies makes them even more damaging.

Economic Theory and Empirical Reality

To everyone but the anarchist, government coercion is sometimes necessary. Just because unions require restricting freedom, then, doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t have laws aimed at giving them a larger role in society.

However, when we consider basic economic theory, it is clear that we should expect these institutions to impose great costs and bring few direct benefits, especially when one considers the alternative of the state engaging in direct redistribution.

Many on the left claim that unions are responsible for improvements we’ve seen in wages and working conditions. In the grand scheme of things, it is difficult to find empirical support for this view. The US after the Second World War, when labor unions were most powerful, had a lot going for it, as discussed in Gordon’s aforementioned The Rise and Fall of American Growth. Among these advantages were the damages inflicted on advanced societies throughout the Second World War, and the fact that in many cases other countries had even more powerful labor unions.

The final questions I’d like to address relate to how much labor unions matter today, and the degree to which their strength or weakness determines the level of prosperity within a society. I will take up these issues in the next article. For now, the point is that unions are a particularly terrible form of regulation from the perspective of economic theory.

According to a recent survey of economists, there is overwhelming agreement in the field that increasing unionization would boost the wages of workers eligible to be members. But when you ask whether more unionization of the American workforce would give a noticeable wage boost to the median household, 23% agree, 14% disagree, and 49% are uncertain. Even that question focuses only on wages and ignores future economic growth. Moreover, only 2% say unionization would have a positive effect on employment, compared to 44% who disagree.

Unions have always been steadfast supporters of the left in electoral politics. There are 4.5 Democratic economists for every Republican, which means that if there is any issue on which you would expect them to be biased, it would be this one. The fact that economists are divided on the topic indicates that support for organized labor contradicts some of the most fundamental and widely held beliefs of the field.

I’m somewhat surprised by the fact that relatively pro-market liberals don’t make arguments similar to the ones I put forward here. For example, Yglesias holds my view that direct redistribution is better than interfering in the economy. Yet I never see him talk about whether there might be serious problems with the way labor law works in the United States. I searched “NLRB” and “National Labor Relations Board” in Slow Boring and only found one result in a post, in addition to a handful of mentions in the comments, and got zero results for “Wagner Act.” Searching for “unions” shows articles explaining why teachers unions are bad, but no in-depth treatments. When Yglesias mentions private sector unions, it’s usually to position himself on the other side of them, like here where he defends Airbnb and points out that hotel workers unions oppose the company. Based on this record, I’m guessing that Yglesias doesn’t particularly like even private sector unions, but would rather not bring up the issue so as to not alienate his left-of-center audience. It’s like when a conservative never mentions abortion except to point out the pro-life position is bad politics. In cases like that, I assume the individual supports abortion rights.

This is unfortunate, as I think that sensible liberals should challenge bad ideas on their own side. Another thing to consider is that people also have a tendency towards a status quo bias. Unions have already gained some degree of power in most industrialized countries, so this creates a disinclination to challenge them, and many who should know better come to even convince themselves that they’re not all that bad. But I think if unions didn’t exist and someone proposed them today, there would be wide recognition among the economically literate portion of the public on both sides of our political divide that such institutions would be cartels, bad for both individual liberty and economic growth.

I don’t like high taxes and redistribution either, and I think any form of the welfare state has serious deadweight losses. But in general, direct transfers are preferable to bans, and especially to government-enforced cartels that create new bureaucracies that go to war with meritocratic principles and often sanction property damage and violence. There are simply better ways to help workers than to support labor unions.

My first exposure to unions was before I worked in online marketing, I had an English Education degree and had to complete an internship by teaching for a semester. We had to sign up for the NEA even when in college, I'm sure to funnel them more money and bolster their numbers - while getting us in the habit of mindlessly supporting them before having real world professional experience.

When I was teaching and interacting with other teachers, the topic of unions came up from time to time. It was a clearly parasitic relationship, the idea being that we were looking out for ourselves against society, namely the parents and government. It was funny hearing leftists online suggest that this was an entirely pro-social arrangement given that actual union members were much more realistic and grounded about the entreprise.

You missed the boat so completely as to call into question what you think a Libertarian is. Labor unions are a free association. No real libertarian would ever want to ban individuals from forming and joining such an organization, as it would limit freedom (the entire point of libertarians is to increase freedom). Furthermore, the increase in cost is a feature, not a bug. Your example of the longshoremen earning a living wage in an expensive place is an example of labor unions working. Importers are free to use alternative ports. Mexico is right there, free of longshoremen. We would see many imports choosing that option if the microscopic impact of longshoremen's wages were in any way significant (they are not).

The entire point of unions is to meet at eye level large corporations that have an unequal ability to suppress wages, especially in small towns where alternative employment is rare. Furthermore, workers favor many expensive, pareto suboptimal career benefits such as employing workers after they are no longer in the prime of their lives. This pushes employers to avoid practices that wear down the bodies of their employees. The policies of layoffs and rehiring is also one that employers love and employees hate. Higher labor costs are worth the lower volatility once an individual is hired. Such policies will be managed one way or another, and labor unions negotiating in a market is superior to the regulatory alternative.

Remember, unions only arose in opposition to market failures in employment, workers compensation and dangerous workplace practices. Unions allowed for private sector corrections without excessive government intervention. The alternative means MORE regulations, a larger, stronger OSHA, and likely a set of rules so cumbersome as to make new company formation rare. We need less regulation and more unions, not the alternative that has restrained our economy for the last fifty years (declining unions with ever increasing regulation).

As with all things, labor unions have a cost. It is a cost their members CHOOSE to bear and benefit from. There are externalities, of course, as all actors in an economy have. This is a fact of life. There are real reasons to oppose unions for public sector workers. That makes sense given the absence of an opposing shareholder (public sector managers have no profit to manage, and no incentives to keep costs down). There is no reason why private sector workers should not have the right to organize and demand a larger share of value added. If this imposes costs on others, so be it. If the cost is too high, the companies they work at will fail. The system works. Private sector workers should enjoy their right to organize, and have the ability to opt out. I would agree with you that workers should have that ability to say no. Requirements that all employees must pay for all union services are wrong. Workers should at the least be able to opt out of political expenditures. Public sector employees should have the right to opt out of all union dues, and frankly should not exist at all, but given the relentless persecution of unions along with the senseless attacks on work in general, this has never been a realistic goal.

The alternatives to the mass unionization the US had in the 1950's and 1960's is mass government regulation and the dumping of corporate externalities on the public. This has been right in line with high taxes on earned income and foolishly low taxes on capital gains. We would be better off eliminating such distinctions and having the same rates on all income of any kind, ideally with an end to corporate taxation (only taxing income distributed to shareholders).