Should All Parents Consider Embryo Selection?

Sperm competition doesn't appear to be doing much

Noor Siddiqui is the CEO and founder of Orchid, a genomics company that helps parents screen embryos for diseases before they are born (interviewed by me here). She caused a stir in August when she went on Ross Douthat’s podcast and implied that embryo selection is something all parents should consider. The madwoman actually said “Sex is for fun, Orchid and embryo screening is for babies.”

I have no moral objection to embryo selection and IVF, and I’m not going to take a position on the effectiveness of screening methods. In fact, I think we have a moral obligation to do what we can to create the healthiest, smartest, and best-looking children possible. I’m interested in a much narrower question here. Are IVF babies likely to be in some ways deficient compared to others? Setting aside the financial cost, inconvenience, and discomfort of going through IVF, is there a reason to suspect that your baby would be worse off relative to a child made the natural way?

Perhaps the best reason to suspect that the answer is yes is the existence of sperm competition. There is something deeply moving about how those little guys struggle so valiantly in the hopes of obtaining a future existence. And the selection mechanisms appear to be intense. According to one academic review,

In nearly all imaginable semen samples, IVF selects for another phenotype of spermatozoon to fertilize the oocyte than coitus does. IVF practitioners and researchers alike have long since acknowledged the differences between the selection of sperm in coitus compared with that in IVF, and they have used these differences to inspire research into how to select the most competent sperm for assisted reproduction and how to engineer methods for selection of spermatozoa in the IVF lab that mimics sperm selection after coitus. When reviewing that field of study, Sakkas et al. (2015) included a section on evolutionary mechanisms used to promote sperm selection after coitus. The spermatozoa ejaculated into the vagina first swim through the uterus and a fallopian tube, in close contact and interaction with female cells and secretions, and perhaps influenced by female peristalsis. Upon reaching the vicinity of the oocyte, spermatozoa are attracted to the oocyte by chemotaxis before penetrating the zona pellucida by applying a variety of means, both kinetic and chemical. In contrast, the phenotype of a spermatozoon selected for fertilizing the oocyte in IVF is one that swims fast over the shorter distances required by various sperm-preparation methods used in the IVF lab. In the case of ICSI [intracytoplasmic sperm injection], the demanding step of penetrating the oocyte is performed by the ICSI operator, and even an almost immotile spermatozoon may be selected. ICSI also removes the selection pressure on the spermatozoon to localize an oocyte in its immediate surroundings and overruns the selection of sperm that occurs after coitus by factors secreted from the oocyte.

The last part sounds bad! In the sex act, each ejaculate contains tens or hundreds of millions of sperm. Only a few hundred reach the oviduct, and of those only one can be the winner.

In contrast, here’s how IVF is described by a fertility clinic.

There are two methods to accomplish fertilization with your eggs during IVF: conventional insemination and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). The type of fertilization method used is determined by your specific clinical situation and your care team.

-Conventional insemination: In this method, the IVF lab team will combine 25,000-50,000 sperm with each of your individual eggs.

-Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI): In this method, the cell layer surrounding the egg (the cumulus cells layer) is removed and the IVF lab staff can identify which of your eggs are immature and mature. The lab team identifies single sperm under the microscope that have normal shapes (including the head, tail, and connection between both head and tail) and normal swimming function. With a very small, specialized glass needle, the IVF lab staff will inject a single sperm with normal shape into each mature egg for a direct approach for fertilization.

So either we filter out 99%+ of sperm and let the rest compete in an artificial environment, or technicians just pick one based on how it looks. The second method, which has almost no selection mechanism, is the default way of doing IVF, making up about three-quarters of all cases.

You would think that a process involving hundreds of millions of competitors with a single victor is going to end up with a better result than simply choosing a winner based on superficial criteria. Even if you create multiple fertilized eggs during IVF and choose the best one based on polygenic screening, it seems like you should still get an inferior result.

Reasoning from first principles, then, I would think that IVF babies should be deficient in some way. But we need empirical evidence to see whether this is indeed the case.

Assisted Reproductive Technology and Health

First, some terminology. Studies in this field will often discuss Medically Assisted Reproduction (MAR) or Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART). The difference between the two is that ART refers only to procedures that involve handling eggs or embryos outside the body, while MAR is the broader category that also includes less invasive treatments like ovulation induction and intrauterine insemination. Sometimes studies seek to learn about the effects of MAR, which includes ART, while at other times ART itself will be the focus. To add to the confusion, IVF and ICSI can be referred to as different processes, while in other cases they are grouped together. For our purposes, whenever IVF is mentioned in this essay, it includes ICSI.

There are three ways to test whether ART leads to inferior outcomes, listed from the least to most reliable methods.

Compare ART children to those born naturally

Compare ART children to those born naturally, controlling for factors that make families that have ART children different from the general population

Compare ART children to other children born of parents who also had fertility problems, with studies involving siblings where one was born naturally and the other was born through ART providing the best possible insights, controlling of course for factors like birth order and age of the mother.

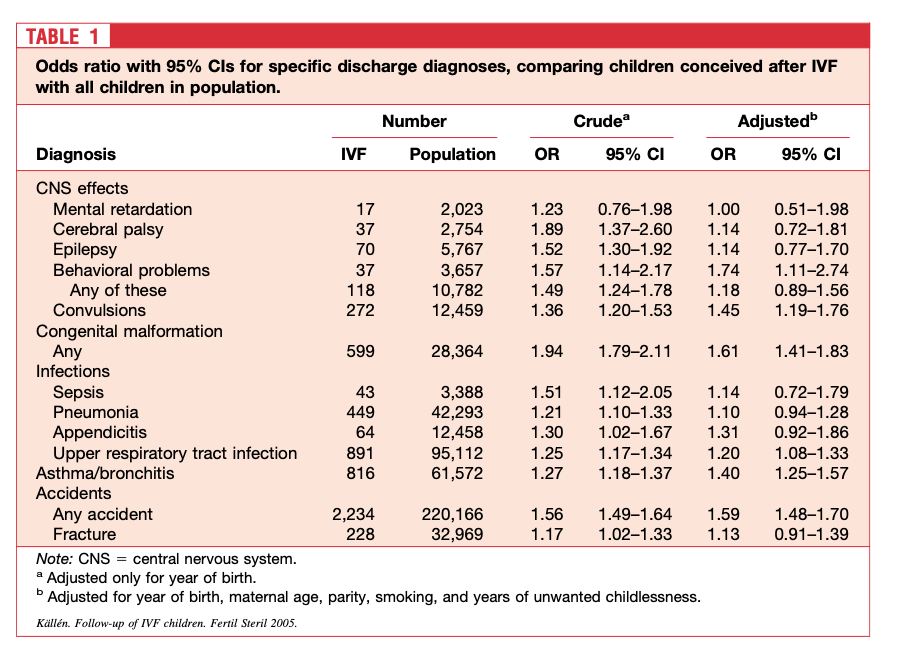

In Sweden, we see that, compared to all children, those born through IVF between 1982 and 2001 are more likely to be diagnosed with nearly every problem examined in the chart below. But if you adjust for certain factors like age of mother, most of these differences become statistically insignificant, with exceptions for behavioral problems (74% higher odds), convulsions (45%), congenital malformations (61%), upper respiratory tract infections (20%), asthma/bronchitis (40%), and any accident (59%).

People generally seek out IVF because they have trouble conceiving, which could itself indicate health problems. In the Swedish study, then, we cannot conclude that the process of IVF itself is the cause of the issues we see. I personally don’t take the “behavioral problems” result that seriously, since it seems possible that people who rely on MAR are likely to “medicalize” issues other parents would not consider worth paying much attention to. We might say something similar about accidents.

Strong evidence for the idea that MAR parents “overmedicalize” comes from a UK study showing that while naturally born and MAR children self-report similar mental health outcomes, when you ask the parents, suddenly the MAR children do much worse. Parents who conceive unnaturally are probably more likely to be hypochondriacs. Nonetheless, the categories of congenital malformations and asthma seem less subjective, and in the Swedish study we see statistically significant results.

A meta-analysis by Rimm et al. (2004) found that across 19 studies, IVF children had a 29% higher chance of major malformations (MM).1 Each study, however, lacked a control group of parents with low fertility who were trying to conceive. Rimm and two of his coauthors came back in 2011 and accounted for research showing that perhaps 40% of the difference between IVF children and natural conception children can be explained by parental characteristics, which we can estimate from comparing children born through IVF to children born of parents who experienced fertility trouble but nonetheless were eventually able to conceive naturally. Once this was adjusted for, there was no effect of IVF on major malformations. According to another review from 2014, “Although ART are associated with a 30% increase in birth defects; subfertile couples achieving pregnancy without ART show a 20% increase.” This is such a tiny effect that there’s a good chance the small residual difference is still due to the issues of parents themselves, since matching to subfertile couples who conceived naturally does not completely control for the problems IVF couples face. For an argument that some residual effect of IVF on birth defects remain after accounting for subfertility, see the discussion on pages 16-19 here.

In the years since Rimm et al., scholars continue to produce studies claiming to find a connection between Assisted Reproductive Technology and health problems without any controls for subfertility. Davies et al. (2012) investigated births in South Australia and found a 28% increased chance of a major birth defect. Yet this was practically identical to the difference between children of couples who conceived naturally with a history of fertility treatment and the general population. Thus, it seems like subfertility completely explains the higher likelihood of IVF babies having MM. The authors seem not to notice this, however, and declare that “[t]he risk of birth defects associated with ICSI remained increased after multivariate adjustment, although the possibility of residual confounding cannot be excluded.” Of course it cannot be excluded. The evidence for the effect of subfertility is right there in the article! See here for a critique of the conclusion in Davies et al. and the response by the authors.

You can still find more recent papers that state offhandedly that ART causes more birth defects, as in footnote one of this 2023 review. Yet there appears to be little research that shows this while giving the subfertility hypothesis its proper due. One exception is a 2021 study that investigated live births in four American states and found IVF kids to have a 15% increased chance of a major birth defect when compared to siblings. This is a small difference and still may be due to the subfertility of the parents. We should take numbers like this to be the absolute limit of any heightened risk.

To be fair, major malformations do not occur that often, meaning that it can be difficult to get enough statistical power in studies involving siblings or even subfertile controls to investigate the question. Nonetheless, the small differences found in the Rimm et al. meta-analysis and other studies without such controls or siblings to compare IVF children to indicate that if there is an increased risk of major malformations associated with ART, it is very small.

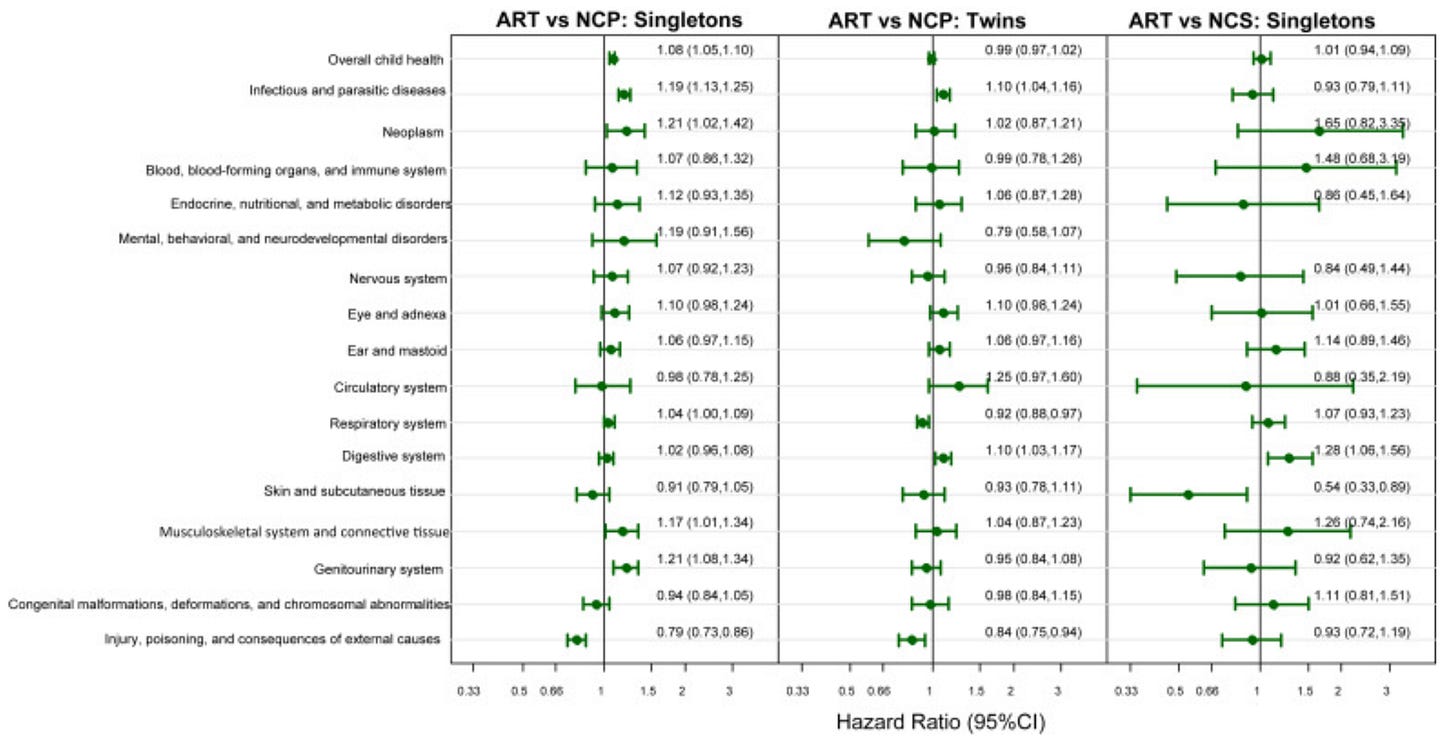

All of this teaches us that we need to be very careful when interpreting data on this issue, even when papers control for factors other than subfertility. Of course, sibling design studies are best of all. One from the UK looked at children born through Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) from 1997 to 2009, for a sample of 63,877. They compared their health outcomes to naturally conceived population controls (NCP) and naturally conceived siblings (NCS). The results are below.

This is a big fat nothing. When you measure against population controls, you get a handful of statistically significant negative health results, and all but one disappear in the comparison to siblings. Note that while in the comparison with population controls, nearly all of the point estimates are positive, in the sibling comparison models they hover around zero, once again indicating that there are likely few if any negative health outcomes related to going through the IVF process.

Cognitive Ability and Academic Achievement

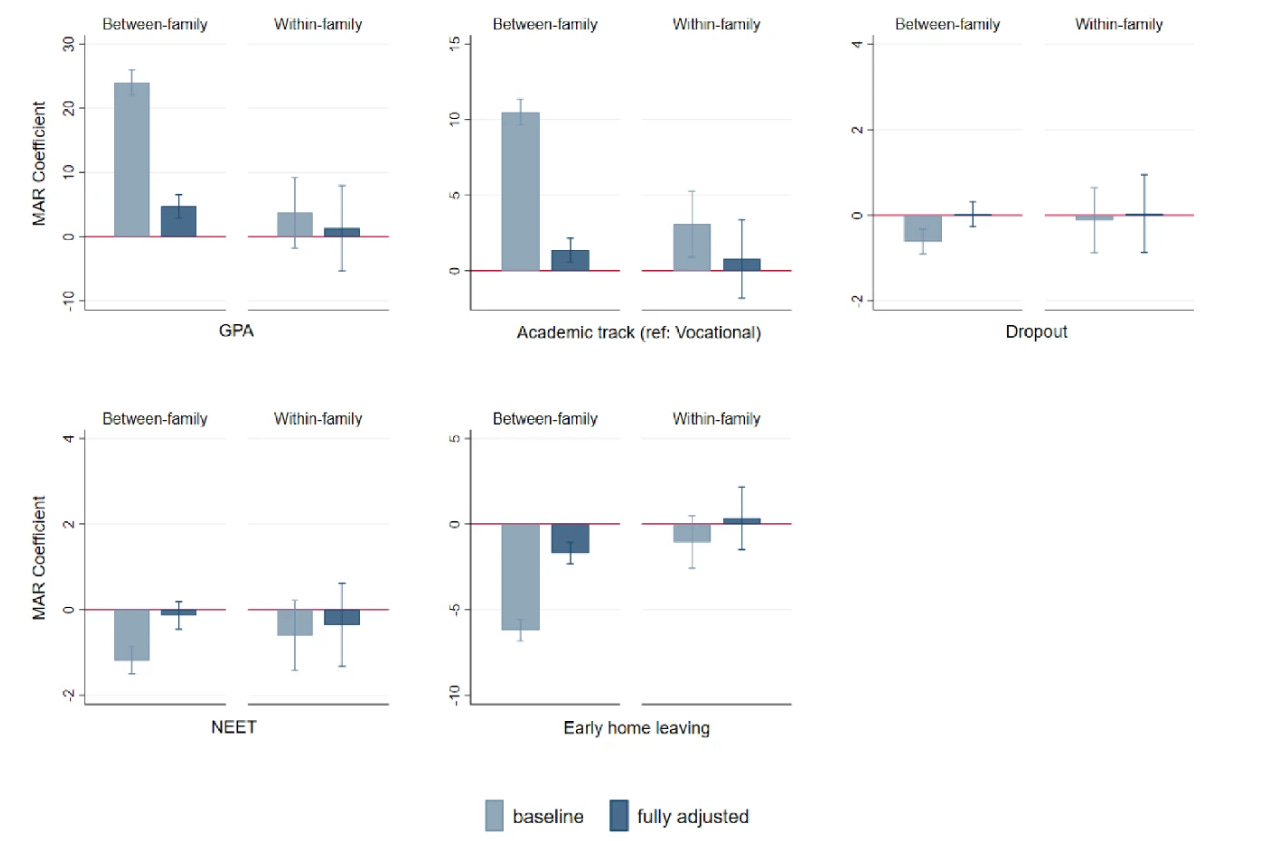

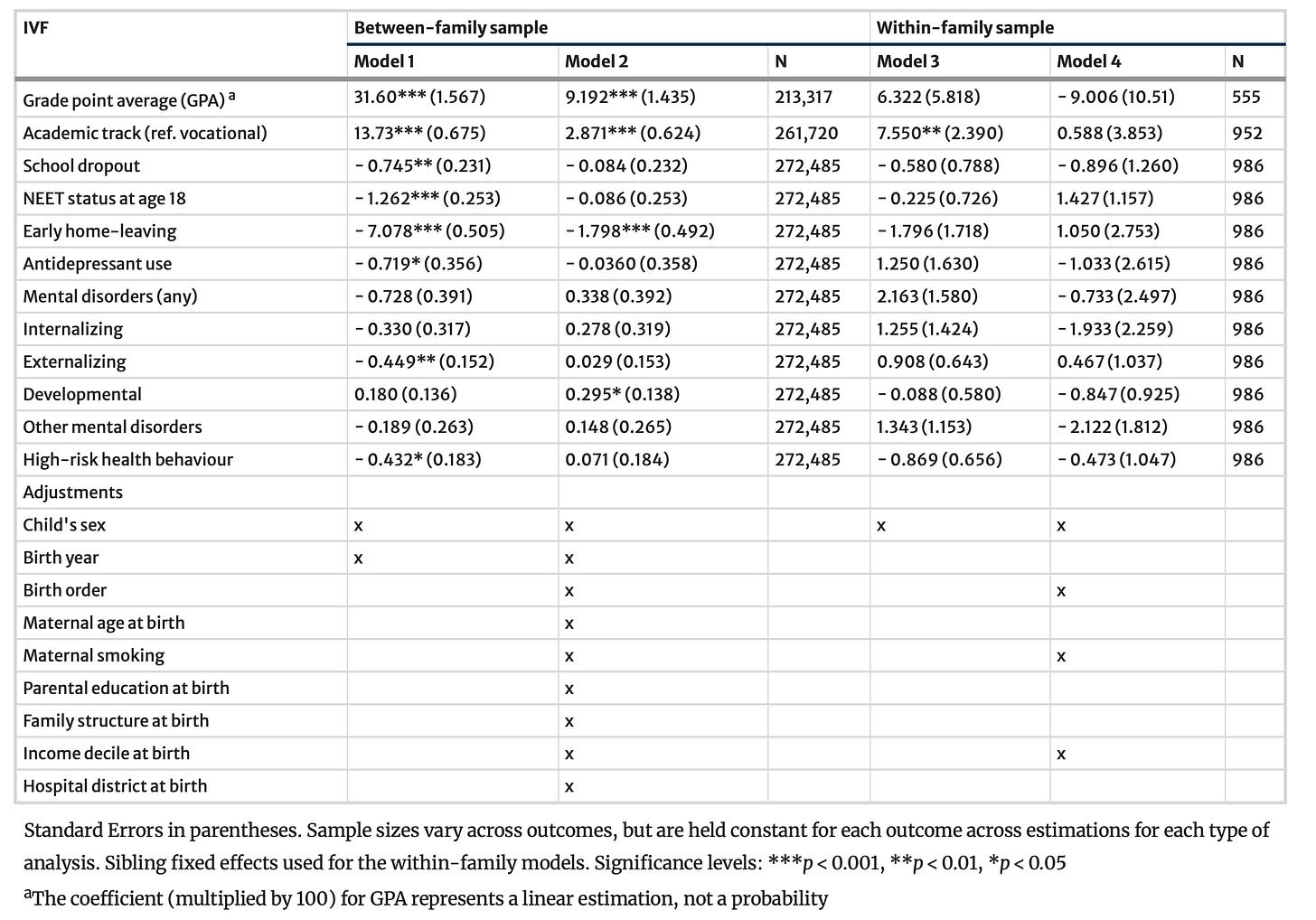

So much for sperm competition doing much good for your health. How about longer term nonhealth outcomes? The best study on this is from Remes et al (2022). It comes out of Finland and looks at all children born from 1995-2000. They were able to do a sibling design by matching births to medications women were on in the time period they had gotten pregnant. The authors tested for adolescent outcomes, namely GPA, being on an academic rather than vocational track, dropping out of school, NEET (not in education, employment, or training) status, and leaving home early. The results of the between-family and within-family (i.e., sibling design) models are below.

MAR kids did clearly better than the general population. The results were attenuated when controlling for demographic factors between families, and then completely disappear when comparing siblings.

The chart above shows the results for all MAR technology. About 40% of the MAR cohort was born through IVF.2 What if we just look at that subsample? Again, we find positive outcomes for IVF kids between families, and nothing going on in the within-family models.

In Denmark, 15- and 16-year-olds born through MAR have higher IQs than the general population by about 0.2 standard deviations, but when controlling for them being higher socioeconomic status, they are actually 0.1 SD below children born into similar environments. This is not a sibling design study and has no control for subfertility, and given the tiny magnitude of the difference and what we know from previous papers, we can probably say that the effect of MAR itself on IQ is approximately zero.

There is one category of outcomes on which some ART children — specifically those conceived through fresh embryo transfer — do worse even compared to their siblings, and that is being born preterm and with a lower birthweight. A Danish study of 3,879 sibling pairs found that when all ART conceptions were pooled together, ART children were on average 65 grams lighter at birth than their naturally conceived siblings, although this pooled figure concealed substantial differences by treatment type. A Finnish within-family study reached a similar conclusion: fresh embryo transfers were associated with modestly lower birthweight even when comparing siblings born to the same parents. By contrast, in the Danish data, children born after frozen embryo transfer were actually 167g heavier than their fresh-IVF siblings who came before. The authors suggested that frozen-embryo transfer might resemble more natural implantation conditions and that embryos surviving freezing and thawing may be particularly robust. There are apparently risks of children being born too large, but it seems that except in extreme cases they’re mostly to the mother rather than the child.

Westvik-Johari et al. undertake a sibling comparison study based on nationwide data from Denmark (1994–2014), Norway (1988–2015), and Sweden (1988–2015), involving over 4.5 million births. Once again, freshly transferred embryos were born with a lower birthweight, but children born from frozen embryos were 82 g heavier than their naturally conceived siblings. However, both fresh and frozen ART children were associated with a higher likelihood of preterm delivery.

To emphasize this point again, even the low birthweight result isn’t proof that ART treatment itself is the issue. After all, among the same parents, there has to be a reason a couple chooses to conceive naturally in one scenario but not the other. Sibling design studies keep the parents constant, but do not fully control for health, since people’s health changes over time. Nonetheless, this is the one kind of negative result of ART that does not disappear when you try to control for subfertility.

Overall, across the UK, Australia, and Nordic countries, the results are remarkably consistent. We can conclude that:

IVF may cause lower birthweight and preterm delivery, though the results are small and even in sibling-design studies might be due to the health of the parents.

Frozen embryo transfer is associated with higher birthweight. You should maybe consider freezing and thawing your embryos so only the strong survive rather than implanting them fresh.

Sibling studies and those that otherwise control for subfertility indicate that there is very little to no impact of the IVF process itself on traits such as health, GPA, IQ, and social dysfunction.

Overall, IVF lets people who are less healthy have more kids. Age and subfertility status are major contributors to negative outcomes, but the IVF process itself isn’t. And on long term outcome traits we care about like academic achievement and NEET status, kids born of higher socioeconomic status (SES) end up above average regardless of how they’re conceived. If you want a smarter and better functioning population, the order of priority in encouraging births should be 1) High SES couples who can conceive naturally; 2) High SES couples who have trouble conceiving naturally; 3) Lower SES couples.

Using MAR or IVF itself doesn’t change health or academic outcomes. Any negative outcomes for ART relative to natural conception are likely due to the traits of the parents, not the process itself, except perhaps for the higher odds of preterm birth and lower average birthweights.

One upshot here is that we should not take seriously people who say they are against MAR because they worry about the selection effects, especially if they don’t worry about the selection effects of letting poor people have kids. Being born to parents of high socioeconomic status is more important for success than the circumstances under which you were conceived. Also cast aside any talk about surrogacy and the “cruelty of taking a child away from its mother.” Given how much socioeconomic status predicts outcomes, for both genetic and cultural reasons, one of the worst things you can do from a public policy perspective is put barriers in the way of smart and wealthy people reproducing, no matter how they do it.

I haven’t looked into every possible disease, disorder, or flaw that IVF kids might have. But I have tried to gather the highest quality studies, and given the wide range of characteristics checked for and the null results across the board, at this point I would be very skeptical of any supposed large negative effects of MAR or ART. There are still studies claiming undesirable effects, but if they’re not using a sibling design method or at least trying to control for subfertility, they are useless for establishing causation.

Isn’t This Weird?

One practical implication here is that the results suggest that, if you trust genomic scores to be predictive, there is a decent case for doing elective embryo selection even if you don’t struggle with infertility. Going through IVF and picking a baby at random won’t lead to any worse results than natural conception on average, so if you can get a handful of embryos and sequence each of them, the outcome should be even better. I’m not taking a strong position on the value of genomic scores, but I would be shocked if they were completely worthless. So if you think the investment makes sense in terms of time, money, and discomfort, feel free to go ahead and try for a superbaby. There’s no scientific reason why Noor Siddiqui’s vision cannot or should not come true.

The question that originally motivated this inquiry was not really practical, but came out of intellectual curiosity about the process of sperm competition. I started out inclined to believe that some kind of amazing selection process must be going on when you begin with hundreds of millions of little swimmers and only one wins. But it looks like nature doesn’t do any better than some guy in a lab looking at sperm and saying “hmm…this one will do.”

What exactly is the point of all these sperm? Robin Baker’s Sperm Wars argues that they’re there to fight off competition from the genetic material of other men, but his theories appear not to have held up well. There doesn’t seem to be much selection going on when individual sperm are fighting with one another and they do not work as teams. Those of us who got here naturally started from sperm that weren’t all that special; they in effect won the lottery.

Maybe we can think of sperm competition as a battle royale. Imagine you put a million men selected from the general population in the same room and dropped a football somewhere at random. Whoever first manages to place both hands on it for at least five seconds wins. Some percentage of men will have no chance at all: the severely handicapped, the weak, the unusually timid, etc. But among all slightly above average men, there is tons of randomness in the process. You wouldn’t expect the strongest man in the room to have odds much better than most others. Conducting a battle royale might on average not lead to a result that is different from just picking a guy who looks like he might be the type to win a competition like this.

It appears as if the only reason male mammals produce so many sperm is that they’re really small and cheap. Many malfunction, but in the end all you need is one that is adequate enough to get through.

At a broader level, I think this says something regarding arguments about playing God. I’m not religious and less likely to fall for the naturalistic fallacy than 99% of people out there. Intuitively though, something tells me that ART should lead to worse outcomes, and I even started out with a scientific-sounding reason based in evolution as to why we should be careful about deviating too much from natural methods of conception.

But my instincts were wrong. Even if ART has some negative effects, they are so small as to be practically untraceable regarding everything except possibly preterm delivery and low birthweight. Doctors or technicians in coats can pick sperm about as well as the billions of years of selection compressed into our reproductive organs. The lesson here is maybe that we should keep messing with Mother Nature. At our best, we are much smarter than her.

Rimm et al., like some of the literature, defines IVF as conventional insemination, and puts ICSI in a different category. The 29% increased chance of MM in the 2004 meta-analysis is the pooled result of children born through both conventional insemination and ICSI.

Although this isn’t clear in the paper, I confirmed with the lead author that IVF in this case includes ICSI.

This was interesting. I wrote about this a while back and came to a different conclusion looking at it more from the prenatal care provider perspective. Here's from that essay "The risk of placenta previa is more than six times higher in pregnancies resulting from assisted reproductive technology (ART) than in those conceived spontaneously. This condition is dangerous because it can cause severe bleeding, increase the chance of preterm labor, lead to low birth weight, and necessitates delivery by cesarean section to protect both the mother and the baby.

This increased risk appears to stem from the embryo transfer procedure itself rather than underlying infertility. Supporting this, a Swedish study comparing individuals using preimplantation genetic testing (PGT)—similar to the approach offered by Siddiqui’s company—with other IVF users found similarly high rates of placenta previa in both groups, indicating that the elevated risk is associated with ART rather than fertility issues."

Here's my post if you want to link to the study: https://annledbetter.substack.com/p/why-i-dont-fear-an-ivf-takeover

It's an interesting post. The big questions, in all of this, is whether natural insemination via sperm competition is optimal and IVF somehow inferior through interfering with the natural selection of the most fit spermatozoon to reach the egg.

The unstated assumption is that the quality of the successful spermatozoon is somehow related to the quality of the genetic material inside it.

Intuitively I find it hard to accept, by what mechanism would a particular DNA configuration packed into a sperm's head affect the mechanical efficiency of the flagellum and link to the ATP firepower of the midpiece's mitochondria.

The reality is, as usual, complex and complicated. Correlating the two populations will be informative, but whether enlightening - with the numbers of confounding variables - I'm not sure about. I'd definitely like to know though.