The Case Against (Most) Books

Taking opportunity costs seriously in the quest for knowledge

Many effective altruists and rationalists oppose reading books. This position is easily mocked, but as someone who is familiar with the way academia and publishing work, I think it has a lot to recommend to it. According to the great moral leader Sam Bankman-Fried,

I don’t want to say no book is ever worth reading, but I actually do believe something pretty close to that…If you wrote a book, you fucked up, and it should have been a six-paragraph blog post.

Ideally, one would like to think that if someone has written a 300-page book, it means that they have 300 pages worth of things to say. My experience is that is rarely the case. People generally have an idea that can be expressed in terms much shorter than that, but extending your idea into a book looks impressive on a CV and gets you invited on TV shows and podcasts.

To take one example, the last book I finished was David Sinclair’s Lifespan. It has three parts, and the last of them is nothing but two chapters about his political and social views, where he addresses issues that are ancillary to conquering aging like what’s going to happen to social security and the impact of a growing population on global warming. He also comes out for universal healthcare, legalized euthanasia, and more income equality.

There is no particular reason that the world’s foremost expert on aging should be expected to have anything new or interesting to say on these topics, and he doesn’t. I would’ve skipped these chapters, except for the fact that I was planning on writing a book review and felt obligated to slog through them. It’s not that a professor at Harvard Medical School can’t have interesting political views, it’s that Sinclair’s opinions are a boring mélange of what one would find across Atlantic think pieces. But for some reason he feels the need to pontificate on various topics that have nothing to do with his area of expertise.

Why? Most likely, he’s simply filling up space. Either he thought the book needed some padding, or maybe he felt the urge to preach about single-payer healthcare and decided to trap readers into hearing his views after he lured them in with the anti-aging stuff.

The vast majority of books are like this in some way. Any Substack essay I have written could’ve been a book if I had the time or inclination to make it into one. You can always add more anecdotes or examples, or elaborate on how your idea relates to adjacent ideas, or find some new way to test your theory. You can also just repeat the same arguments ad infinitum. I’ve previously noted how Sinclair kept harping on his optimism regarding how we’re going to cure aging again and again, constantly making the same points while using slightly different words.

My experience in political science is that what will often happen is that an academic will get a paper published in a major journal. Then it becomes easy to sell a book to a publisher in which you just present the results of that paper and add a bunch of useless words. Something like this is the norm, not the exception. From talking to economists, I gather that they’re pretty negative on books, and this is one of the many ways they’re more sensible than other academics.

The issue here is opportunity cost. Let’s say you want to learn about why people form the political opinions they hold. You might read a 300-page book. Or, for the same amount of time and effort, you might read two chapters of that book that are 20 pages each, plus 15 different articles that are 15 pages each, plus say 5 Wikipedia articles that are the equivalent of another 35 pages. Something like the latter is usually the better path. And most academic articles are, to be frank, full of filler too, so you’re probably better off skipping the intro and conclusion of many of them. Substacks and Tweets are actually efficient methods of transferring information because you cut out so much of the useless fluff people include when they’re trying to build a CV.

It’s not that nothing can be learned from reading the 300-page book. It’s just that reading the book is a large commitment, and puts you at the mercy of one author, who probably took way too long to make his points for reasons of ego and career interest.

Three Kinds of Books to Read

For the reasons given, I think we can use more careful thought about when and how often you should read books in their entirety. Saying you should read fewer books makes an individual sound lazy, which is why people rarely give that advice. But we should take opportunity costs seriously. Given all the other things you could be reading like scientific papers and news magazines, not to mention other things you could be doing with your time, which non-fiction books are worth reading cover-to-cover? I argue that there are three categories of works that you may consider digesting in full.

Category 1: History books

When learning history, one can always decide at how granular of a level to investigate an era, topic, or important figure. Most social science or political science books are padded with filler because there are only so many interesting things you can say about most ideas. But history is different; you can always go into more detail about World War II, or the life stories of Ottoman sultans, or the fall of Rome. Even a thousand-page book on a historical topic can only capture a small slice of reality. The returns to reading history are somewhat linear — five hundred pages on World War II give you more insight than a 5-page summary, which gives you more than 5 paragraphs. If you were inclined to read 5,000 pages, you’d get more still, but we generally don’t have the time for that. Most things are not like this. I can’t say the same for, say, Jonathan Haidt’s Moral Foundations Theory. I think it can be explained in a few paragraphs, plus some charts. I loved David Reich’s Who We Are, which used the tools of paleoanthropology to go into the history of various major regions of the world. Unlike with Sinclair’s book, it didn’t feel that much of my time was wasted.

Category 2: Books of Historical Interest

You may want to read Kant, Plato, and the Bible, because many people have been reading them for a very long time, and you want to be a participant in the wider culture. I don’t believe in the “wisdom” to be found in Great Books (see below). But I want to understand my fellow man. A large portion of people who live under the same polity as I do think that the Bible is the literal word of God, so it’s useful to get a glimpse into their reality. Similar things could be said about the Koran or the writings of Confucius. It’s like how one reason to read the NYT is that everyone else is reading it. So not only do you get the value of the news itself, but also insights into what’s considered culturally and socially important.

Category 3: Genius Takes You on a Journey

This final category covers works where you have some combination of a brilliant author who is a great storyteller and an important topic. I check out all of Steven Pinker’s books, because he’s a pleasure to read, he addresses fascinating issues, and I have trust in his judgment and intellect. One of the most valuable books I’ve ever read is Judith Rich Harris’ The Nurture Assumption, as I think the question of nature versus nurture is one that individuals should dig deep into before they even begin forming political opinions.

Some books fall into more than one of the categories above. I’d put On the Origin of Species in categories 2 and 3. The Federalist Papers are worth checking out for insights into the thinking of the men who founded this country, and they might even have some useful things to tell us since we’re still living under the system they designed.

I’ve published one book and have another on the way. I like to think that they’re both combinations of 1 and 3. My book on American foreign policy had two chapters devoted to international relations theory, and the rest gives you my take on topics like the US-Soviet relationship in the 1920s and 1930s and the war on terror, making it useful as a history of American foreign policy. If it was an entire book on IR theory detached from any kind of deep historical analysis, and those have been written, reading it all would probably be a waste of your time. My next book serves as a history of where wokeness came from, and provides practical political advice on what to do about it.

Against Great Books

When I wrote my piece on Enlightened Centrism, some took issue with me saying that I don’t believe in Great Books. After thinking about the topic a bit, I’m more certain that I’m correct. One might read old books for historical interest (Category 2), but the idea that someone writing more than say four hundred years ago could have deep insights into modern issues strikes me as farcical. If old thinkers do have insights, the same points have likely been made more recently and better by others who have had the advantage of coming after them.

This isn’t an issue of thinking every previous generation was dumb. Imagine hearing that we just discovered a tribe in the Amazon that previously had no contact with other humans. Nonetheless, this group developed a writing system. Living among them is an individual who they consider the world’s greatest philosopher. Being part of an isolated tribe, this philosopher has had no formal education or exposure to any modern ideas. He doesn’t know about evolution, has never logged on to the internet, has learned nothing of human history outside of the oral tradition of his tribe, and doesn’t even know whether the world is round or why the seasons change. Would it be plausible to believe that this Amazon philosopher had something to teach us about the way our government should be organized or whether the US should adopt protectionist trade policies?

Most people I think would say no, regardless of how smart he is. We might be fascinated by the Amazon philosopher, but wisdom one can learn from requires some baseline level of knowledge. If you reject the possibility that the Amazon philosopher has great insights into the modern world, on what basis would you trust Ancient Greece?

It’s not simply that the ancients had less information and access to empirical data, but ways of thinking have improved over time. Bertrand Russell once quipped that Aristotle believed that men had more teeth than women, but it never occurred to him to open his wife’s mouth and start counting.1 One of the best essays I’ve read in a long time is “You live in a world that philosophy built,” by Trevor Klee. We take the basics of the scientific method for granted today, but only after generations of newer scholars throwing off the shackles of official dogma.

Again, I feel the need to emphasize that none of this is to say I or my favorite contemporary writers are smarter than Aristotle. Would it have occurred to me to start counting women’s teeth to test a hypothesis? I’d like to think of course I would. But what if I had never been exposed to scientific reasoning before and everyone I had ever known had argued by simply making things up? Things that seem obvious today were beyond the grasp of most humans throughout history.

This is why I don’t buy the Lindy argument, that it’s worth reading certain thinkers because they’re the best minds humanity has ever produced. The smartest person in the world with a preschool-level education will not have much useful to tell us. And I say this as someone who thinks the vast majority of modern social science is either useless or wrong. Still, if 1% tells us something new and profound, then previous generations did not have access to a great deal of important knowledge.

While people seem to think it’s hubris to dismiss previous generations, to me this is actually the humble position. No human being is smart enough to have much interesting to say without a wide base of knowledge produced by countless others.

It’s true that modern people, due to dogma, can in some ways be stupider than ancients. The obvious example here is “what is a woman?” But that’s not an argument for reading ancient thinkers. It’s an argument to read modern writers who don’t have certain mind viruses.

A few months ago, I picked up Meditations by Marcus Aurelius, after Ross Douthat said I subscribe to pagan morality, which I took as a compliment. I wanted to be deeply impressed by the book, because it sounds good to have a worldview with a basis in an ancient philosophy. But it’s all basic stuff like “don’t worry about what others think of you,” and “control your emotions.” Maybe it was mind-blowing the first time someone said these things, and it’s definitely sort of cool that a Roman Emperor can communicate with you across two millennia. But I’m 100% certain that if you gathered some passages from Marcus Aurelius and hired a halfway intelligent blogger to produce content made to sound like Marcus Aurelius, nobody would be able to tell the difference.

You might want to read the Stoics out of historical curiosity. I’ll claim them as part of my intellectual tribe to signal that I reject the moral underpinnings of both Christianity and wokeness, the two most powerful faiths in our society. But anything intelligent or insightful they said you’ve probably absorbed already through run-of-the-mill blogs and self-help books, shorn of all the stupid things that inevitably made their way into their writings.

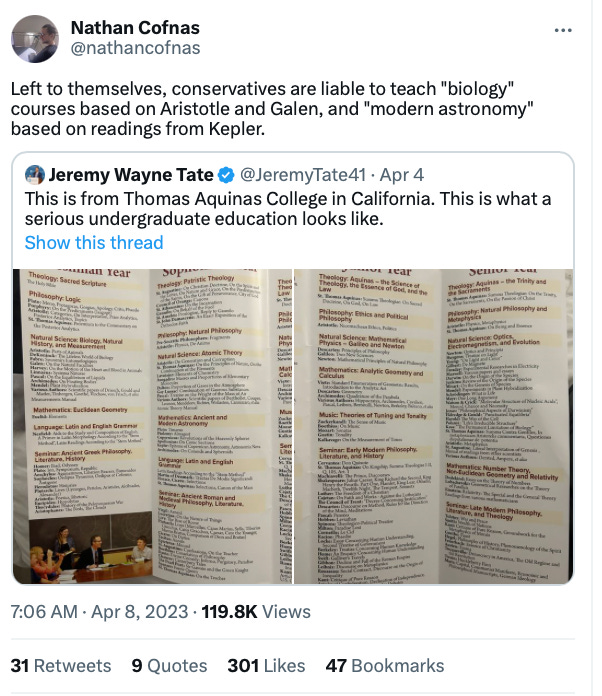

I’m not mad at people who want to read old books. The problem is that I get the sense from some of them that they think they gain more wisdom than others by doing so. Last month, there was a tweet going around that showed how absurd this worship of the past can get.

I think what’s going on here is that religious conservatives are into theology, and that’s one field where there indeed hasn’t been much progress over long stretches of historical time. So for theology to be a credible human endeavor, they need to pretend biology, economics, etc., are like theology, where an ancient thinker is just as likely to have a worthwhile idea as a modern scholar.

Anyway, there’s much more that could be said, but since a major point of this article is that intellectuals tend to go on for too long, I’ll stop here, and simply end by noting that although I think there are many valuable ideas in this essay, I won’t be turning it into a book.

Reading the link I provided, it seems like Aristotle might have actually been relying on the observations of others, who he thinks counted male and female teeth. The quote is

Males have more teeth than females, in the cases of humans, sheep, goats, and pigs. In other species an observation has not yet been made.

So it sounds like he may have been using proper scientific procedures, and we can only fault him for at worst not double checking. Then again, it’s unclear what he meant by “observation” here, it could’ve been something like “some other guy said it,” in which case Russell’s point would stand. And why would the ancients have gotten the number of teeth wrong across multiple species? It makes sense if they were just making things up, but not if they were actually checking their work. (Updated 5/11/23)

Most old books are a rebuke to the modern reader, as they demonstrate the crudity of contemporary language and the sloppiness of our thoughts.

I would add textbooks to the list of books that are worth reading. Not always, but often its the best way to learn a complex new field. Open to suggestions of alternative formats, like reading papers--though if you want an intro & problems, textbooks are still great.