I’ve never written much about the fertility issue, as I’ve generally found it hard to explain why it varies so much across populations and therefore come up with something original to say. But I’ve always been interested in the topic. In late September, I was at the Manifest 2023 conference, and stumbled upon Robin Hanson holding court in a small circle on what I now like to call his “Kings and Queens” theory of declining fertility. Usually, we think of status in relative terms, and there are sound evolutionary reasons for this. From this perspective, if people in your life treat you poorly, you feel like you are low status, and you get an emotional boost when other individuals act as if you’re someone important and worth listening to. If status signals influence fertility, then, this would indicate that it would be through those we get regarding how we are doing relative to other people. But that wouldn’t explain anything about differences across societies, since we can say status is zero sum in all cases, though maybe with some caveats.

Hanson’s theory is that all people in developed states today feel high status at some level. Paradoxically, we use absolute measures of wealth to judge our relative situation. The idea is that through most of human history, most people were extremely poor, but a few elites lived well and had a chance for them or their offspring to become kings and queens. For those people, it made sense to limit fertility and invest in one or a few children. Because we’re all now walking around with full bellies, low parasite loads, etc., we all think we have a shot at being Genghis Khan, having our son become Genghis Khan, or marrying our daughters off to him. We therefore limit fertility, even if in our current day this is maladaptive.

I thought that this idea was brilliant the moment I heard it, and joked that it’s really funny to imagine the poorest Americans sitting there living in squalor, at least by our standards, and thinking that “we’re going to be kings and queens” because their bodies tell them that they’re living it up, which they objectively are relative to their ancestors. Using absolute living standards to judge relative status seems like it would’ve made sense for much of human history, and in fact signals of absolute wealth seem like they could in some ways be more physiologically plausible than those based on how we are treated by and relative to other people. An empty belly or a physical illness seems to much more reliably affect behavior than most kinds of social interaction.

Soon, I found out that Robin had written about this Kings and Queens (KAQ) Theory in 2021, and he argued that it not only explains fertility, but a lot of other things we see since the Industrial Revolution, including greater tolerance, the rise of hobbies, and individuals demanding more of a role in the political system they live under. In many different ways, regular people act more and more like aristocrats, or potential kings and queens.

Predictions and Empirical Analysis

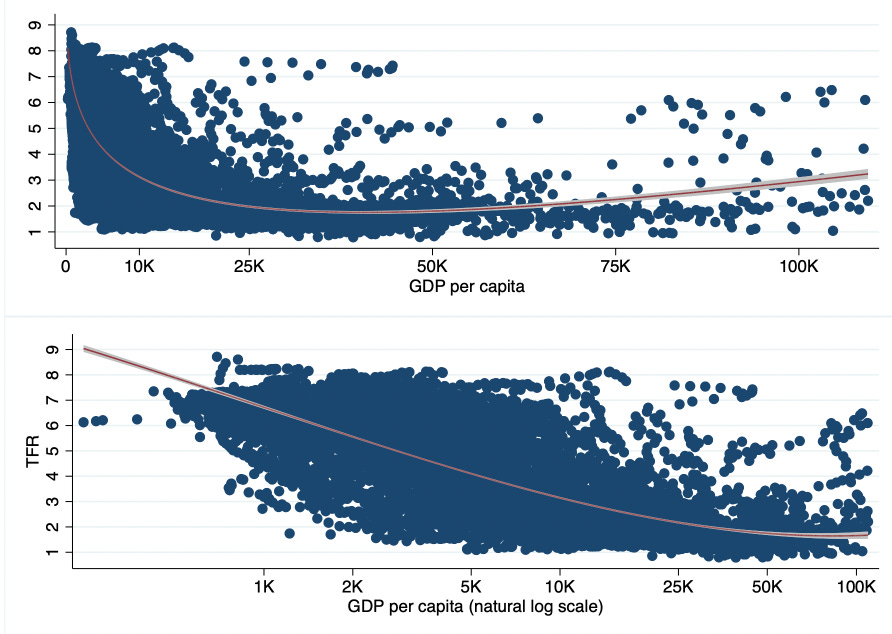

Are there ways to test this theory? The first thing KAQ predicts is that as income goes up, fertility goes down. This is what we see in the chart below from Our World in Data. Note that GDP per capita is adjusted for the cost of living.

The second thing I would expect is that the effect would change at different levels of wealth. Imagine three tiers of countries.

Low-income: Few people feel like they can become kings and queens.

Middle-income: Some people feel like they can become kings and queens.

High-income: Everyone feels like they can become kings and queens.

It is of course already well-established that there is a robust negative relationship between fertility and income. But KAQ expects it to be strongest among middle-income countries. For low- and high-income nations, the relationship will be much weaker, and idiosyncratic variation in culture and other variables will have more of a role to play in explaining fertility differences. We could expect a moderate negative relationship at the low-end, since even the poorest countries today are rich by historical standards. But when a country gets wealthy enough, it becomes what Hanson calls “status-mad” across the board.

What do “low-”, “middle-”, and “high-” income actually mean? I’m not sure. In The Roman Market Economy, Peter Temin comes up with an estimate of GDP per capita of $1K in the Roman Empire in 1990 dollars. The Romans famously worried about the low birth rate among their elites, and so we might estimate that it would only take a few thousand dollars per capita for human beings to feel “rich” in an absolute sense.

This was a relatively wealthy society by historical standards though, as GDP per capita in Europe was a few hundred dollars a year before the Industrial Revolution. A few thousand dollars a year to feel like an aristocrat must be a high-end estimate, implying that the vast majority of countries today have populations that are nearly universally drunk on status.

The table below shows the correlations between income and fertility depending on what we consider a low-, medium-, or high-income country, for all years between 1950 and 2019. The data it is based on can be found here.

We have a total of 10,108 observations, with each observation being a country-year. I set the lower bound at either $1K, about the GDP per capita of Ancient Rome, or $2K, and I consider countries high-income if they have a GDP per capita of either at least $5K a year or $10K a year, since those seem at the approximate levels at which even the poorest people can live like elites did in the vast majority of past societies.

We find support for KAQ theory here. In each model, the correlation between income and fertility is strongest in the middle band, although the theory certainly looks stronger if you choose $10K instead of $5K as the high-income threshold. Once you get past the larger number, the relationship disappears completely. If we wanted to justify using the $10K threshold, we might say that there is bound to be a cultural lag. While everyone may have evolutionary reasons to feel like a potential king or queen at $5K, usually norms and culture don’t change overnight, which is why it might take time for society to adjust to the new reality.

It is also possible that we use a combination of relative and absolute signals to judge our status, but for everyone to get status drunk it takes a level of wealth beyond the point at which an ancient aristocrat lived in order to overcome the fact that in any society some people are constantly reminded by others that they have lower status. If we go a step further than before and only look at countries with a GDP per capita of at least $20K, we find a slightly positive 0.19 relationship between wealth and fertility.

Regardless, we should be hesitant about being confident about any of these thresholds, since uncertainties in this type of analysis tend to pile on top of one another. We don’t really know what level humans would need to reach to feel wealthy in an absolute sense, GDP isn’t an exact measure of well-being, and even if it were what actually matters is not necessarily the average but how many people fall into higher or lower bands of wealth. Instead of coming up with our own numbers a priori, it’s probably better to explore the data and see if we can find the expected pattern where the strongest relationship between GDP and fertility is somewhere between the highest and lowest ends of wealth. I suspect $10K might be too high for our high-income floor, but I’m more confident saying that we definitely shouldn’t go much above that. Pretty much everyone in a society where GDP per capita is $20K a year is rich by any reasonable historical standard.

Figure 2 below shows the relationships between wealth and fertility for countries with a GDP per capita of at least $10K in selected years.

We can see that there are a handful of resource rich states that have a lot of kids. From the looks of Figure 2, this may be distorting the data. In order to check if this is a problem, we can calculate the relationship between wealth and fertility at higher incomes after we exclude Algeria (DZA), Equatorial Guinea (GNQ), Gabon (GAB), Kuwait (KWT), Oman (OMN), Qatar (QAT), Saudi Arabia (SAU), and the UAE (ARE). The correlation between GDP and TFR among high-income countries then goes from -.07 to -0.17, becoming stronger, but nowhere near the effect that we find among middle-income countries. I’m unsure if it makes sense to exclude those countries, as the KAQ theory holds that after a certain level of wealth idiosyncratic cultural factors come to matter more, and being a Muslim nation sitting on a sea of oil certainly counts as one of those. Nonetheless, it seems that the effects of the resource-rich states balance each other out. Qatar has a major effect on the slope of the line in some years by being rich and fertile, while in many years countries like Algeria and Oman are just barely above the $10K a year threshold and likewise exert an outsized influence but in the opposite direction.

Figure 3 below shows the relationship across the income scale, with GDP either being unaltered or having undergone a logarithmic transformation.

The logged data in particular shows a very nice fit. If you simply regress TFR on logged GDP per capita, you get an R-squared of 0.56, implying that wealth alone can explain the majority of the variance between countries.

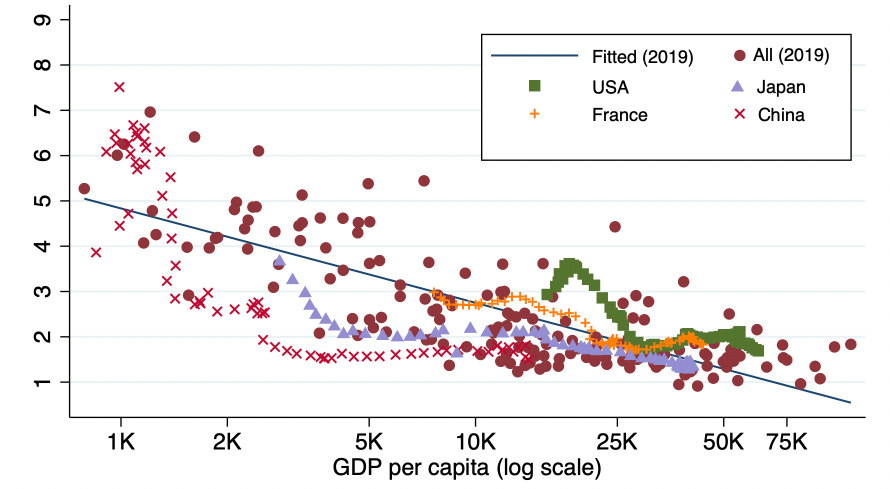

Just for fun, here’s what it looks like if we plot fertility for the US, France, Japan, and China for all years against all other countries in 2019.

We see a precipitous drop for China and Japan very early, and then a leveling off. France gradually declines between $10K and $25K and then stabilizes. The US sees a positive association between GDP and fertility at lower levels, but fertility plateaus at around the same point that it does for France.

There of course could be confounding variables explaining the observed data. Imagine that there was a cultural shift starting in the 1960s that reached different parts of the world at different times. GDP has been going up over the last several decades, and fertility has fallen, so the fact that they seem connected could be due to cultural changes that operate independently of economic growth.

To test for this, I ran a regression that had TFR as the dependent variable, and with GDP and year as predictors, for countries with a GDP per capita of less than $10K. Both variables are statistically significant below the p < .001 threshold. The effect of an increase of $1K in wealth goes from 0.42 fewer children per woman to 0.4 when year is added as a control, a negligible difference. Adding year to the model where GDP predicts fertility increases the variance explained from 38% to 51%. A model with year alone as a predictor only explains 18% of the variance, making it less important than wealth.

Another way to check for time dependence is to see whether the pattern of middle-income countries having the strongest relationship between GDP and fertility holds across the decades. Figure 5 shows that it does.

No matter which decade you focus on, middle-income countries consistently see the strongest relationship between higher wealth and lower fertility. For high-income countries, the relationship mostly hovers around 0. It reached a high of 0.38 in the 1970s, which was, as indicated by the data above, driven by Gulf Arab countries seeing a spike in living standards due to high oil prices.

Overall, I think this is very strong evidence for an effect where the relationship between wealth and fertility starts out weak and negative, becomes strong and negative as more and more people feel that they and their children are potential kings and queens up to the $5K or $10K range, and then disappears as practically everyone is subject to this effect.

Objections to KAQ

KAQ seems to roughly fit the data. Does it make theoretical sense? I can think of at least a few critiques.

Critique #1: Very few people would historically have been in a position to become kings and queens. So there’s probably no all-purpose “Kings and Queens” module in the mind.

I think one way to get around this is to say that we are disproportionately descended from people who took radical gambles and succeeded. It’s true that most peasants throughout history did not have a chance at becoming rulers. But those that did and succeeded passed on their genes to an extremely disproportionate degree. Half of one percent of all men on earth famously got their Y chromosome from Genghis Khan. That’s a massive evolutionary payoff, and one could imagine a succession of waves where more and more people come to be descendants of those who had successful strategies for navigating the upper reaches of politics.

Critique 2: Aren’t siblings useful?

If you want your child to be a king or queen, wouldn’t it help to give them siblings? On the one hand, they might kill each other in succession battles, and as Hanson argues, they could compete for the resources of their parents. On the other, they could be allies and help one another along. Ideally, you’d maybe want one boy and a lot of girls, to invest everything into making the former a ruler and marrying the latter off, but humans can’t choose the sex of their babies.

Critique 3: The mechanism must be too fine-grained.

The idea of KAQ is that humans have this module where they limit fertility because they think that they might become kings and queens one day. But the ultimate goal is to actually seize power, at which point you should want to reap the rewards of this strategy.

This means we have to imagine something in our evolutionary programming that says “limit fertility when you are close to becoming a king, but be fruitful when you actually become a king.” But it seems like your absolute standard of living would be similar if you’re almost a king versus actually being a king. So how would a theory that is based on absolute living standards explain wealth being a signal to limit fertility in one situation but not the other?

One could argue that we use absolute living standards to decide we’re aristocrats, but then rely on signals of relative status to decide we’re kings, like if you hear trumpets playing before you walk into a room. When I pointed this out to Robin recently, he acknowledged that this was indeed an implication of KAQ in a postscript to his article. But this makes the theory somewhat ad hoc, relying on signals of absolute wealth in one situation and then conveniently switching to relative status in another.

Other Theories that Fit the Data

Are there other theories that can explain the patterns that we see, keeping in mind that we must be able to tell an evolutionary story that makes sense? One might expect we have some kind of programming where we are supposed to seek out stimulation to improve our cognitive functioning, become more interesting to mates, or whatever. Through most of our evolutionary history, you wouldn’t have to worry about this tendency going haywire, since most people just sat around on the savannah or in mud huts all day and didn’t find too many chances to be entertained. But then at some absolute level of wealth, the world becomes too much fun and we end up not having kids. We instead go to the movies, watch TV, gossip, play sports, or do whatever else people do to pass the time.

This would I think explain an overall negative relationship between wealth and fertility, but not the U-shape of the relationship. Do options for entertainment and diversion increase most at the middle-income level? One could speculate about when the opportunity costs of having kids are highest, but I would naively expect more money to be able to buy more vacations, entertaining gadgets, and experiences up to just about any level of wealth. Does a person gain more opportunities for enjoyment by going from an income of $5K a year to $10K, or from $10K to $100K? One thing that seems plausible is that 1-2 children per woman is the natural lower limit in any society, $10K a year gets you to that point, and then there isn’t much room for the fertility rate to go lower.

Recently, Hanson came up with another theory, which says that we evolved to imitate successful people, and due to selection effects, among elites the most successful around them tend to be those who had the fewest kids. On average, having a small number of children wouldn’t have been a good evolutionary strategy, but it would sure look like it if you are only looking at the top levels of society. Historically, elites have often seen collapsing birthrates. As for why this limited fertility norm has only spread to the general population now, one has to “again postulate that humans encoded this behavior as something that mainly makes sense for parents who are relatively rich and high status, but not otherwise.” This strikes me as not very convincing, and perhaps not even internally consistent. The theory holds that evolution equips us with a feeling of where we are in a hierarchy based on absolute wealth, but that mechanism is at the same time maladaptive, because it causes elites to fall prey to selection effects. Why would we have such a complicated way of interacting with the world, only for it to be defective both historically and in modern times?

A simpler version of this imitation theory, one that doesn’t rely on threshold effects, might say that the most successful members of society were always those who came from families that limited their fertility. But most of the population usually did not have enough exposure to elites to notice. Under this theory, elites have always been behaving maladaptively and falling prey to selection effects, but not enough people have been elites for this to change our evolutionary trajectory. Now, with greater wealth and communications technology, more and more people are exposed to the ultra-successful. This would explain both decreasing fertility as wealth increases, and also decreasing fertility as time moves forward, given the spread of radio, TV, and the internet. I was surprised to just find out that there are even today countries in the world where internet connectivity is still in the single digits, and those places have very high fertility. This theory may also be consistent with a threshold effect, where you’re either aware of elites and how they live or you’re not, with greater wealth not bringing any more awareness. We can call this “elite exposure theory.” I think that for it to work, one must in addition assume that at the level of a village or whatever, the most successful members of society didn’t actually limit their fertility that much, but once people expand their horizons, the true outliers in status and prestige disproportionately come from small families. Thus, the blind heuristic of “imitate successful people” leads to different fertility outcomes depending on how broad a perspective individuals take regarding their wider society.

Misalignment as the Human Condition

I think that there are strong empirical reasons to believe that there is some kind of threshold effect on fertility, where it drops when people reach a certain level of wealth. Here I’ve only looked at fertility at the national level. But the theory should apply at least as strongly to class differences. We should expect a strong negative relationship between income and fertility in poor nations, but a weak one or no relationship in wealthy countries where everyone is status drunk. I’m unaware of data on fertility by wealth or income in developing states, but I’m sure something is out there.

I find KAQ theory appealing because it fits the data, the idea can help us understand things other than fertility, Robin Hanson personally explained it to me, and most of all, it’s funny. That said, it has a few theoretical problems, the most serious being it doesn’t explain how humans switch from low-fertility mode to high-fertility mode when they transition from being close to power to actually achieving it.

Whatever the true explanation is for the threshold effect, it’s likely to have a mishmash of components that seem to be in tension with one another. I’ve already mentioned the possibility that under KAQ we rely on signals of absolute wealth to decide that we’re aristocrats, but signals indicating relative status to consider ourselves kings and queens. This seems unlikely, but humans are complex, and they clearly rely on absolute signals for some things and relative signals for others, so we can’t completely rule out that this is how it works.

Similarly, it’s not impossible that the opportunity costs of having children increase more rapidly between the income band of $2K to $10K than any other. We’d have to come up with reasons why, and we probably could if we were motivated to, but who knows if we would be correct? The advantages and disadvantages of elite exposure theory are similar. Occam’s Razor would seem to suggest that distraction theory or elite exposure theory are both superior to KAQ, so I would lean more towards either of them since they are arguably just as consistent with the data.

One thing that seems certain is that there have been different selection pressures operating across populations. For example, Europeans were relatively unique in mandating monogamy even for rulers, and this had downstream effects on the way society was organized. This poses an obvious problem for KAQ theory. And it is just one example of a region-specific effect; there are surely a thousand others, whether we look at recent centuries or the more distant past. That brings up another difficulty in thinking about all of this, in that we have to assign different weights to various parts of the human past, whether our time spent as hunter gatherers, farmers, or people living in modern developed states. Traditionally, scholars argued that most of our evolutionary history was spent as hunter gatherers, so the impacts of recent evolution are likely to be negligible, but genetic research has discredited that framework. When the environment shifts dramatically, the speed of evolutionary change takes off, and what’s difficult about reconstructing the influences that shaped humanity is the fact that we’re a species that is remarkable precisely for repeatedly transforming its environment and changing the way it lives.

In at least one way it’s easier to predict the future of human evolution than to reconstruct its past. If the threshold effect does exist, for whatever reason, modern society must be selecting against it. We’re all Kings and Queens now, and the future belongs to those with traits that are less ill-suited for the world as it currently exists. Yet whatever those traits are, they’re unlikely to always remain the most adaptive under all circumstances, since as a species we almost certainly haven’t undergone the last major shift in the way we live. Some misalignment between how evolution has shaped us and what leads to the most reproductive success at any particular moment is likely to always be with us. In that sense, the modern world is not as unique as most of those who write about low fertility might think.

While I think these are fascinating theories that likely have some degree of truth...

What about the very simple theory that people have fewer kids when their opportunity cost to having kids rises?

I bet that explains most of the decline.

You are making this waaaaaay too complicated. If you were to visit some of these poorer countries, you would immediately find that in most of them, the idea of parents providing a quarter century or more of full financial support for their children is a totally alien concept. Before WW2 in this country, it was still pretty common for kids to start working full time immediately upon completing primary school. They would continue to live with their parents, helping with the household expenses, until they got married in their teens and began the cycle for a new generation. Children in such societies are a huge financial boon for their parents. Not having them makes survival more difficult. In our society, parents are expected to shovel most of their life's earnings into the bottomless pit of child rearing and college educations in the hope that maybe their kids will one day help defray the cost of three bowls of gruel a day in a nursing home.