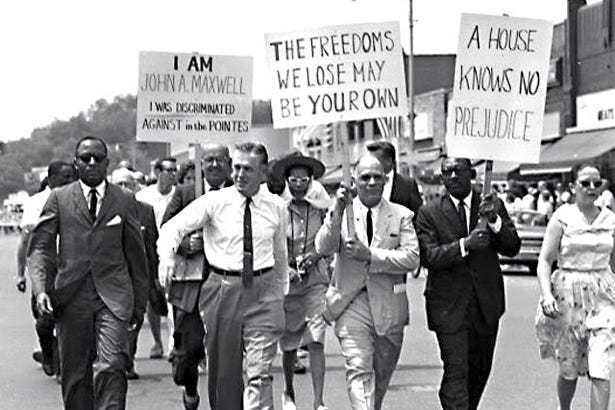

After becoming governor of Michigan in 1963, George Romney made a name for himself as a champion of racial justice. He called discrimination the “most urgent human rights problem” in Michigan, protested along with black activists, and issued a proclamation for “Freedom March Day” when Martin Luther King visited his state. This was out of step with the larger Republican Party, which in 1964 picked a Senator who had voted against the Civil Rights Act as its presidential nominee. Still, Romney was invited to the Republican National Convention that year, where he fought to put civil rights into the party platform, pointedly refused to endorse Goldwater, and denounced “extremism and lilly-white Protestantism.” When in 1967, Detroit was engulfed by race riots, critics of the civil rights movement thought that they had been vindicated. But so did Romney, telling the citizens of Michigan that society needed to address the root causes of such violence. Running for president himself in 1968, he met with Black Panthers, posed for photos with Saul Alinsky, and told white Americans to “listen to the voices from the ghetto.” Again, this wasn’t what Republican voters wanted, and they picked Richard Nixon instead.

Over half a century later, George Romney’s youngest son was sitting in his Capitol Hill townhome when he noticed a group of protesters outside marching towards the White House. The Senator opened the door and joined them, and when a reporter asked why, Mitt Romney responded that “we need to stand up and say that black lives matter.”

In understanding what the last sixty years of conflict within the Republican Party have been about, these stories are telling. If you’re a conservative, you’re likely to say that the base has been pushing back against a woke establishment that tends to surrender to the left on controversial issues. To liberals, Republican moderates have been a bulwark against grassroots extremism and bigotry. Whichever spin one puts on this conflict, the point is that there are ideological differences at its core.

While there’s something to this story, it’s also incomplete. One might be tempted to see both George and Mitt Romney as either, depending on one’s political orientation, brave champions of tolerance or self-righteous scolds, and argue that this is what has alienated them from the base of their party. Yet this simple characterization glosses over something that is more commonly missed: on race-related issues, Mitt Romney is far more conservative than where his father was. He’s even further to the right than Richard Nixon, who in 1968 beat the elder Romney by playing to the white backlash to civil rights.

It can be difficult to make direct comparisons like this. But, in his time, George Romney had serious policy disagreements with the right flank of his party on civil rights. Meanwhile, Mitt Romney became a Senator in 2019, and, especially after voting to convict the president in his first impeachment trial, was regularly praised by the Washington establishment for being the one Republican who would stand up to Trump. Yet the battles between the president and his most prominent critic on the same side of the aisle were remarkably substance free, at least when it came to public policy as traditionally defined as something that exists along the right-left axis. The same year that Romney voted to convict Trump for withholding aid to Ukraine, Ruth Bader Ginsburg died and the liberal establishment pressured the Utah Senator to once again defy his party by rejecting Amy Coney Barrett. Romney refused, and sighed to an aid that “Well, I guess that will be it for all my new friends.” He liked Trump’s judges, which tend to be the main part of a president’s domestic legacy, and by and large did not object to the personnel that he appointed to run the federal bureaucracy. Romney wasn’t in the Senate when Trump signed the tax cut that was the signature legislative achievement of his first two years, but it was the kind of reform that he would have enthusiastically supported.

It’s not that one can’t find policy differences between Trump and Romney. It’s that these differences are small given the extent to which the educated public perceives them to be political enemies. Other Republican politicians have been able to selectively defy Trump’s policy agenda to a similar degree without incurring the wrath of the former president or his most ardent supporters. Of course, the main reason behind the antagonism between Trump and Romney isn’t rooted in ideology but the actions and behavior of Trump himself. Romney does not believe that presidents should lie all the time, engage in casual bigotry, withhold aid from foreign leaders in order to extract political favors, or try to overthrow the results of an election. These are the main divisions within the Republican Party in the Trump era. Yes, it’s also true that Trump would’ve never marched with BLM. But even on issues related to race and crime, Romney did not distinguish himself by being particularly liberal in the summer of Floyd. His deviations from right-wing orthodoxy at the time were similar in type and magnitude to those of Trump himself.

Romney: A Reckoning, by McKay Coppins, is a biography heavily focused on the political portion of the life of its subject, particularly recent history. The author was given an unusual degree of access to Romney’s journal and personal papers and communications, in addition to being able to interview the man himself, his family, and those who have known him over the years. What emerges here is not simply an interesting portrait of one individual, but a story that provides deep insight into what has happened to the Republican Party and the conservative movement over the last few decades. If Trump personifies the hopes and dreams of the insurgent side, Romney represents everything that they are rebelling against. But it would be a mistake to see the conflict as it currently stands as one primarily over ideology or even values. Rather, the fight is both shallower and deeper than most political struggles. It is short on policy differences, while also revolving around deeper divisions regarding what makes us who we are and how we classify “us” and “them” before even beginning to think through a tribalist lens.

Two Revolutions

Trump becomes a feature character only in the second half of Romney, but his shadow hangs over practically every anecdote and event. Coppins makes this explicit in the epilogue, when he goes out to Romney’s family compound on a lake in New Hampshire and reflects on just how different the man in front of him is from his main antagonist.

At one point, Romney takes a gaggle of grandkids out wakeboarding and becomes so engrossed in telling me about the John D. Rockefeller biography he’s been reading that he doesn’t realize two of his grandkids have pushed a third off the back of the boat. By the time Romney notices, the marooned kid is bobbing in the water several hundred yards off.

“Guys,” Romney grumbles, turning the boat around as the perpetrators double over in laughter.

Watching Romney in this setting, I can’t help but think of a certain former president, cocooned in his Palm Beach Xanadu with his third wife, fuming over something he saw on cable news, walking into ballrooms to bask in the applause of strangers.

Romney is simply puzzled by what Republican voters see in Trump. He obviously hasn’t been the only one. After years of trying to understand Trumpism, more perceptive analysts have come to realize that the movement is mostly a cult of personality. The man simply hates the right people and is bolder and more shamelessly confident than any of his opponents. It’s not what he has actually promised to do as president, nor even some kind of generality like “at least he fights,” unless one is talking about how much he fights for his own narrow interests rather than those of his supporters or the movement he represents.

Of course, Trump’s act wouldn’t work in the contemporary Democratic Party. There are different archetypes of leaders, and which one rises to the top in any particular community depends on the characteristics of its members. Trump is a perfect fit for the modern Republican Party, which is animated by people who have a combination of an inferiority complex towards more sophisticated elites and a sense of superiority in relation to the sexual nonconformists and dysfunctional minorities their supposed betters claim to speak for.

Romney, in contrast, is the straight out of central casting leader of those who are happy with their lives and the society they live in. Few men who are tall, handsome, married to their first wife who they still dot over, and surrounded by a gaggle of grandkids — all, as far as we know, still identifying with their biological sex — are enthusiastic Trumpists.

To understand the Trump-Romney rivalry, it’s important to note that there have been two revolutions within the conservative movement since the 1960s, the first practically complete and the second still in progress. In terms of ideology, there is the conservative takeover, which has made Republicans and the judges and officials that they appoint more reliably right-wing. That battle is basically won. Romney, Liz Cheney, Ted Cruz, and Donald Trump all love the same Supreme Court justices. Then there is the revolution of the riff-raff. These people don’t have ideas about whether the Republican Party should be more right-wing or not, but rather want leaders who flatter them, and make them feel heard by expressing agreement with their conspiracy theories and Manichaean worldview in which elites are consciously scheming against them, whether through demographic warfare, collusion with globalist institutions, or Big Pharma implanting them with microchips and suppressing the truth about ivermectin.

The Tea Party was a sort of hybrid movement of these two forces. If you listened to the claims of its leaders, they were fighting for fiscal responsibility, but the rank and file were strangely also obsessed with asserting that Obama was born in Kenya. Birtherism was of course the original issue that made Trump into an identifiably right-wing celebrity. Still, when it came to the 2012 election,

Romney had made up his mind in favor of running, convinced that he could court Tea Party voters while staying true to himself. The real meat of the movement, he’d decided, was fiscal policy. That’s what they were always shouting about, wasn’t it? Unchecked government spending and excessive regulations and too-high taxes — this was where he’d win them over. “I didn’t see it as a populist movement at that point,” he’d later tell me. “I saw it as, these people are really concerned about something I’ve always been concerned about — the deficit and the debt.”

Lest one think he was only moving right on fiscal matters, Romney also played to the conservative base on immigration, promising that his policies would make people living in the country illegally “self-deport.” After losing in 2012, he was criticized for being too harsh on the issue not only by the media and the RNC, but by Trump himself. This only added to the absurdity of the situation when, a few years later, Trump would shoot to the top of the polls in the Republican primary with anti-immigration as his main issue. When Ted Cruz tried to position himself to the right of Trump here, it didn’t work, just as how the DeSantis strategy of being “more Trump than Trump” has so far similarly failed this time around. While a conservative ideologue might care about the specifics of immigration policy, the riff-raff, while having some distaste for demographic change, are far more interested in Obama’s birth certificate, and finding a politician who will play to their fantasy of having discovered something important that will lead to the current object of their rage rotting in a jail cell.

If Trumpism was about issues, whether social or fiscal, there could be something that the Republican establishment could do to mollify its base. But Trump remains in control of the party because that’s not what any of this is about. Rather, the man is mind melded with the Republican base, genuinely sharing their distaste for foreigners and the gender non-conforming, along with a conspiratorial view of the world. Trump also has the personal characteristics that they want in a leader. People can change their positions to win over voters, but not who they fundamentally are.

The title of the book seems to be based on the liberal author conflating the two revolutions. He wants Romney to confess that he has had a role to play in the slide towards Trumpism based on the ways in which he compromised his integrity in the past. The problem with this view is that Romney is actually conservative! So when he moved towards the Tea Party in 2012, he wasn’t being particularly dishonest, at least by the normal standards by which we judge politicians. It seems that the most dishonest position that he ever took was when he convinced himself to be pro-choice in order to win the governorship of Massachusetts, which was an instance of him playing to a left-wing electorate. One thing Coppins seems particularly offended by is Romney having accepted Trump’s endorsement in 2012, but he now justifies this by saying that Democrats aren’t forced to answer for every crazy thing that any left-wing celebrity who endorsed them has ever said, so why should he have had to? This makes sense to me. It doesn’t seem that Romney did much to help the riff-raff revolution along. In fact, by becoming the nominee in 2012, he probably helped delay its ultimate triumph by a few years, while later showing unusual courage by standing up to Trump after joining the Senate.

The Biomechanics of Romney Hate

Even by 2012, Romney’s advisers knew he didn’t fit with the then emerging Republican Party. Yet he was able to do enough to give the base what it claimed to want on fiscal policy and immigration to win the nomination. In the Trump era, however, as the riff-raff revolution arrived at a much more advanced stage, Romney could not stay true to himself and also remain in good standing in the party. Now, the question wasn’t whether you would reduce spending or not, but if you were willing to shamelessly lie to protect one man’s ego by denying the contents of a phone call transcript or the fact that he lost an election and tried to overturn the results. While running for Senate in 2018, Romney is taken aback by a woman who asks whether he would take action to shut down CNN, the New York Times, and the major broadcast networks. He responds that of course he won’t, and is rattled that Trumpism has reached even Utah. Voters no longer even felt the need to hide their desire to hurt others by making plausible sounding arguments about the budget.

In one interview with Coppins, Romney worries that the Republican Party is in some kind of moral death spiral, in which reasonable people of good faith are leaving, therefore surrendering more and more ground to the crazies and making the problem of being a club for the stupid and mean spirited even worse. Romney’s perfection isn’t simply too much for the modern Republican voter. It was his Achilles’ heel in 2012, as Obama was successfully able to shift focus away from cultural issues and win over bitter Midwestern whites by demonizing the wealthy. When Romney ran for governor of Massachusetts and his campaign cut an ad about how much he and his wife loved each other and their children, voters hated it because they refused to believe anyone could have a relationship like that. He would later reflect that “I was accused of being inauthentic. But in reality, that’s just who I am. I’m the authentic person who seems inauthentic.”

This is an issue with Mormons more generally. They are the nicest people one can meet, but broadly disliked relative to other religious groups. When an elder in the church asked Romney if he would consider starting a Mormon ADL, he responded that prejudice against the faith wasn’t really a problem and they should focus on bettering themselves instead. This is despite the bigotry that Romney and his family faced while he was running to win deeply Evangelical states during his two presidential campaigns. Mormons are attractive and have large families that they love. Unlike the ADL, wokes, “Great Replacement” obsessives, or the Q types worrying about the trafficking of adrenochrome, they don’t care all that much what you say about them. For the more jealous among us, this makes them even more frustrating.

As much as the Republican base has come to hate him, one of the most heartening parts of the book is realizing that the feeling is mutual when it comes to the more Evangelical and downscale wings of the party, along with the politicians they tend to support. Mike Huckabee is a “huckster” and a “caricature of a for-profit preacher.” Michele Bachmann is “a nut case.” On Pence, Romney says that “no one had been more loyal, more willing to smile when he saw absurdities, more willing to ascribe God’s will to things that were ungodly.” Despite his strong Mormon faith, Romney’s cosmology is largely deist, and he has undisguised disdain for those who would imagine a divine will working its way through our politics.

I lost track of how many times he comments on the intelligence of others. On Rick Perry: “his prima donna, low-IQ personality doesn’t work for me.” Romney appears to give a lot of thought to the question of whether Trump is actually as dumb as he seems, carefully considering Jared Kushner’s theory that there’s a method to his madness, but comes to the conclusion that “he’s not smart. I mean, really not smart.” Despite some misgivings about DeSantis, he concedes that he’s at least “much smarter than Trump.” Romney’s entire plan for creating a third party appears to be to team up with Joe Manchin, adopt the slogan of “Stop the Stupid,” and then say, “this party’s going to endorse whichever party’s nominee isn’t stupid.”

Romney also discusses a colleague who once had a good reputation but has spent the last few years destroying it by kissing up to Trump. “He isn’t married. He doesn’t have any kids,” Romney reflects. “I don’t know that he spends a lot of time thinking about legacy.” This seems to be a (very) thinly-veiled reference to Lindsey Graham. At one point, Romney speculates that Mike Lee doesn’t like him because, in addition to being given more deference as an elder statesman of the party, the junior senator from Utah is too tall and physically towers over his colleague. “Maybe, he just can’t stand being in my shadow.” Romney’s enemies are not only much stupider than he is, but also short and gay. Contempt for his opponents is actually a trait that he shares with Trump, and it’s therefore perhaps unsurprising that Romney liked the future president and considered him a harmless amusement when he was only a reality TV star and not the leader of the Republican Party.

My favorite Romney clip is of him responding to getting booed at the 2021 GOP state convention in Utah. He had become fixated on a woman with a child by her side who was screaming at him at the top of her lungs. “Aren’t you embarrassed?” he sneers, with the intonation he might use if he was encouraging his grandson to get back on his bike after falling off.

I found this clip deeply moving in a world of Republican politicians who have never found an argument too stupid or demagogic for them to repeat as long as they believe it might make some red-faced woman who can’t control herself in public happy.

Despite his respect for pure brain power, Romney feels the most disgust towards smart politicians who should know better but play to populist resentment and push narratives like that of the stolen election. Josh Hawley and Ted Cruz receive particular scorn here. Romney even says that, in contrast, he is at least able to work with those like Ron Johnson who are legitimately crazy. In his analysis of the modern Republican Party, all of his opponents are either stupid, or smart and soulless. Yet Romney seems to ignore another category, which is the smart politician who has come to actually believe in the populist style, either through rationalization or because he has had his brain turned to mush by the same paranoid right-wing echo-chamber that has wreaked havoc on the mental well-being of conservative voters. This oversight is ironic, given that Romney reflects on the ways he has compromised his own integrity in the past. Yet there’s a difference between fudging your positions a bit as you try to win a primary, on the one hand, and denying the benefits of vaccines or being complicit in a plan to discredit the entire democratic process on the other. While Romney might have a good theory of mind when it comes to understanding the stupid or the slightly dishonest, he’s fundamentally too decent to grapple with a new category of Republican politician that lacks even the ability to distinguish truth and fiction.

The Personal and the Political

Most presidential candidates want to achieve power because they have a kind of grand vision for society. Coppins finds no such desire in Romney. Rather, he genuinely believes he’s the best person for the job. This is an aristocratic conception of power and might be enough to gain it in a society without major moral divisions. His unwillingness to compromise on how he perceives basic reality, or indulge in dumb populist tropes with regards to economics or the dangers of foreigners, and his contempt for those he considers beneath him, are similarly admirable.

Being anti-populist doesn’t mean denying that there are problems in society. Rather, it acknowledges that things are good from a historical perspective, and rejects a brand of politics that does an extremely poor job of identifying what those problems are, much less finding solutions to them. The answer to bad elites is better elites. That is, Mormons coming out of the world of venture capital rather than those with backgrounds in community organizing.

A less neurotic and more confident conservatism would embrace Romney for his sense of superiority because it is justified. It would realize that there is no wisdom to be found among the masses, and especially not among the low IQ and poor, whether they are black and urban or white and rural. Unfortunately, many intelligent conservatives have come to the conclusion that the kind of society they want will require becoming more like the left, and in some ways worse.

Yet it would be a mistake to simply assume that hitching conservatism to Trumpism has been good for the former. Many educated Americans are willing to accept reasonable arguments for low taxes, a limited federal government, tough on crime policies, rolling back the excesses of civil rights law, and other positions that the conservative movement has been arguing for over the last sixty years. Yet they rightly recoil from conspiracy theories, concerns over supposed demographic warfare, aspiring authoritarianism, election denial, and other beliefs indicating stupidity or malevolence that have come to be associated with the American right. The fact that modern conservatism repulses educated people has led powerful institutions to become more liberal, regardless of who wins elections. At the same time, it was the left that originally taught us that coercion works, and when all is said and done there’s a good chance that the more aggressive attitude of the Trump era will end up serving a larger purpose by fundamentally changing the incentives that individuals and institutions face. While DeSantis will likely lose the primary, “DeSantisism” might turn out to be more important than Trumpism in terms of its long-term effect on our politics. My impression is that Romney, like many anti-Trump conservatives, can at least live with DeSantisism, even if it’s not their preferred approach to governance.

A conservative who has gotten on the Trump train can find support in Coppins’ book for the more confrontational and tribal approach that the right has taken over the last several years. Romney himself has no shortage of grievances when it comes to being smeared or treated unfairly by the left. He expresses dismay that Biden gave a speech in which he basically said that anyone who opposed his bill on voting rights, which Romney did, was acting out of racist motives. In the 2012 campaign, Harry Reid told blatant lies about Romney not having paid taxes and ended up getting away with it. Yet to exaggerate the slights against one’s side, that is, to take such incidents and say that they put us in a state of “cold civil war” or on the road to conservatives being imprisoned, is to indulge in pure hysteria, not all that psychologically different from black activists who take a single case of injustice and start talking about genocide.

A more sophisticated case for Trumpism as a style wouldn’t invoke anything that Democrats have done, since they’ve generally respected American political norms much more than their opponents have, but the laws of political economy, in which the natural state of the world is that government power is always expanding. This means that those who believe in freedom will have to behave morally worse than their opponents — that is, lie more, appeal more to base impulses, and violate democratic norms — to have any hope of accomplishing their political goals. I’m not sure if I buy this, but if I was going to make a case for conservatives indulging in tribalism and their persecution complex, that would be it. From this perspective, the two revolutions within conservatism cannot be easily separated. The more that the right adopts unpopular policy positions, ones which I mostly agree with, the more it needs to fight dirty in order to subvert public opinion and the ossified power of established institutions. It may require a movement to believe it is fighting on the side of democracy to be effective in undermining it.

Putting aside any questions of political strategy, I just really like Mitt Romney. In Bronze Age Mindset, we are asked to imagine “a Mitt Romney, but different… a Romney who actually was capable of acting like he looks, and was worthy of his looks.” The real Mitt Romney may not be a Nietzschean hero but he’s certainly one for Nietzschean Liberals. I’d obviously prefer that he not have marched with BLM or voted to confirm Ketanji Brown Jackson. But the fact that he is fundamentally superior to his adversaries weighs heavily in my worldview. That he understands this and spends a lot of time thinking about it, treating his critics with aristocratic contempt rather than a kind of Trumpist rage that is often the mark of an insecure and unstable psyche, makes him even more endearing. Romney is a natural aristocrat in the Jeffersonian sense, one we would all be lucky to be ruled by in a society with a more functional political system.

In the last chapter, it becomes clear that even at 76, Romney isn’t finished. Given the course of the man’s life, one has to believe that even if his plan to create a high-IQ party doesn’t work, he’s going to move on and try something else. Maybe he will save the Republican Party from populism. Or maybe not. Either way, Mitt Romney is going to be fine. Although he believes that, given his family history, he doesn’t have much time left, I imagine that even the thought of an impending death must not be that bad when you have so many grandkids that you’ve lost count. Most people can’t be Mitt Romney. But we can all take as many incremental steps as we can away from loserdom, a process that also takes us further away from the spirit of populism. Whether we want to nonetheless adopt its style with strategic goals in mind is a different question.

This blog surely wins the prize for most consistently striking contrast between the posts and the comments.

"Few men who are tall, handsome, married to their first wife who they still dot over, and surrounded by a gaggle of grandkids — all, as far as we know, still identifying with their biological sex — are enthusiastic Trumpists." Not my observation AT ALL. Trump voters of my acquaintance and age cohort are precisely this, men circa age 60, conservative Catholics, married to their first wives, typically grandfathers. Not all are tall and handsome. Most are professionally accomplished.

Your vision of Trump voters is clearly mostly driven by your own contempt for him and them, and not data driven. Dig into the survey data more. You are the professional pundit around here. You can do better.

"Putting aside any questions of political strategy, I just really like Mitt Romney."

It shows.