Beyond the Culture War: Getting Serious about Reducing Crime

Red states are not doing any better

There’s a recurring debate about crime on X. It goes through the exact same cycle every time.

Conservatives: Look at those blue cities and how out of control they are

Liberals: Actually, Red States have much higher crime rates, har-har-har

Conservatives: Because they have black people! Oooh where’s Steve Sailer, wait until he sees this

Number one reflects the views of mainstream conservatives, and is the type of argument you would hear on Fox News. The third point is put forward by those who consider themselves edgy thinkers, more sophisticated than your average consumer of slop political content, although it is increasingly breaking into the conservative mainstream.

Pointing to demographics as an explainer for crime doesn’t provide much policy direction, other than perhaps as an argument against concerns over disparate impact. When it comes to policy debates, the main question we always end up discussing is whether Republicans or Democrats are better at fighting crime.

The recent murder of Iryna Zarutska brought this issue once again to the forefront. Charlotte is a blue city, in a state with a Republican legislature but a Democrat governor. On X, conservatives blamed lenient criminal justice policies for Zarutska’s killer being out on the streets, a point that is often made alongside statements that this is “what the left wants” or something. Yet state governments have power over cities, and if there is no difference in violence between red and blue states, as I will show is the case, it would indicate that Democrats aren’t necessarily the problem. Nonetheless, I would argue that there is a sense in which the left is at fault for the high rates of crime the US experiences, but to find our villains we need to go back to the 1960s and 1970s. I conclude by discussing what a more serious anti-crime agenda, one that goes beyond culture war point scoring, would look like.

Race and Poverty Matter, Party Doesn’t

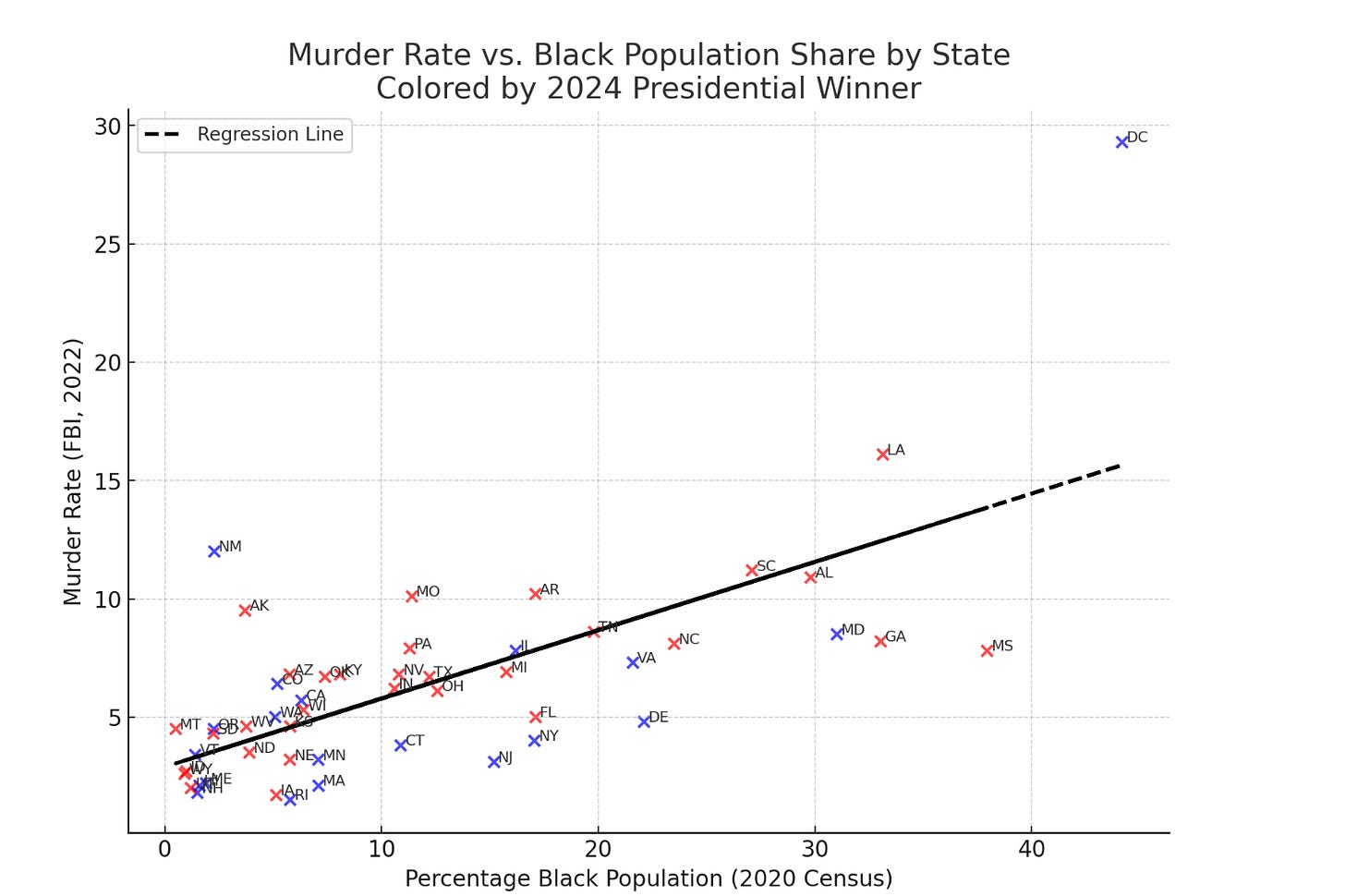

First, let’s start with establishing the link between race and crime, which has to be factored out before we consider anything else, given the strength of the relationship. I’m going to focus on homicide, since that is the most important crime, a good proxy for public safety, and less subject to variance in reporting. Here is the percentage of each state, along with Washington DC, that is black plotted against murder rates, with each point colored red or blue depending on how they voted in 2024.

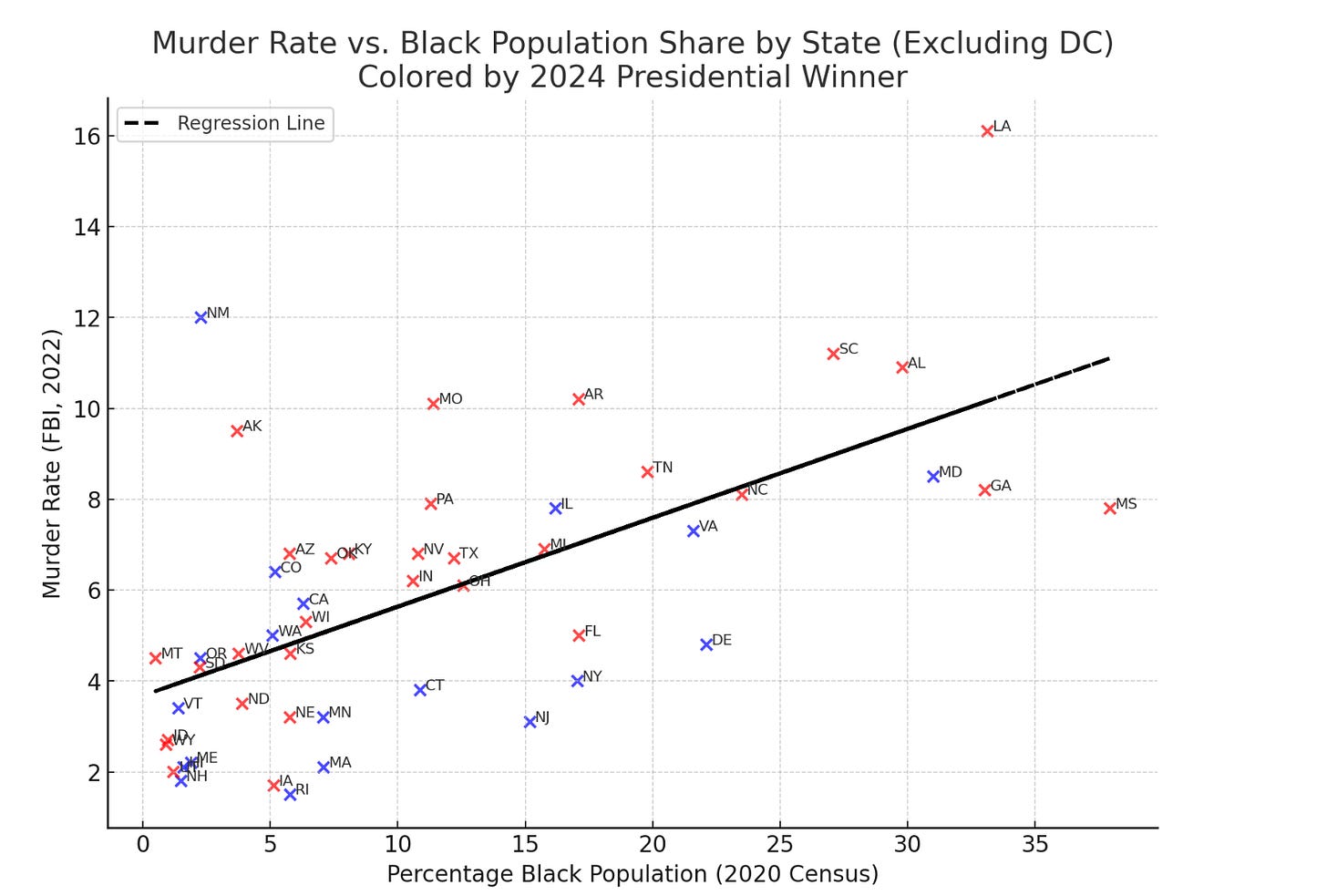

The inclusion of DC throws off the scale. Here is the chart without the city, which doesn’t change much.

When DC is included, the correlation coefficient is r = 0.7. Otherwise, it is r = 0.62.

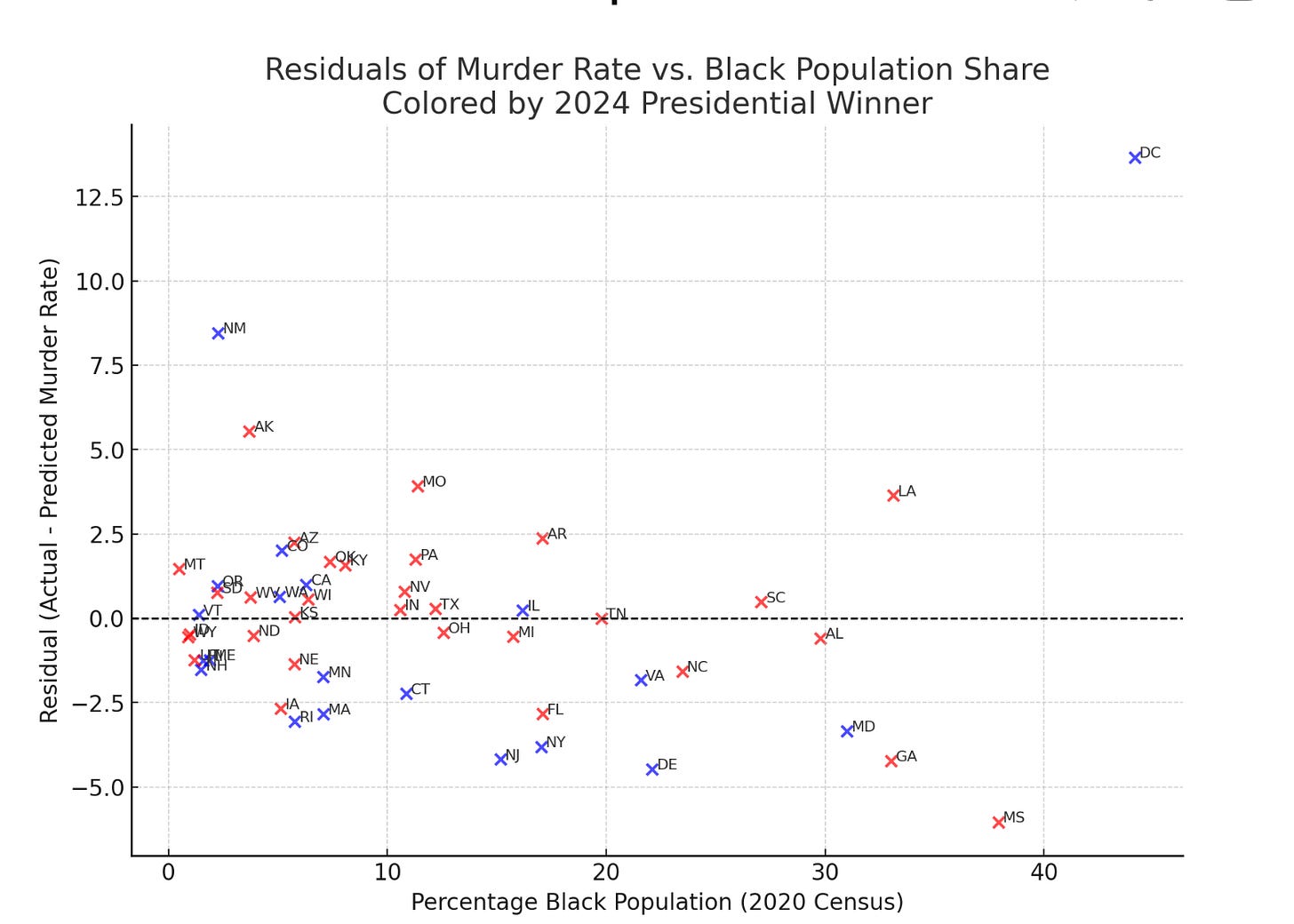

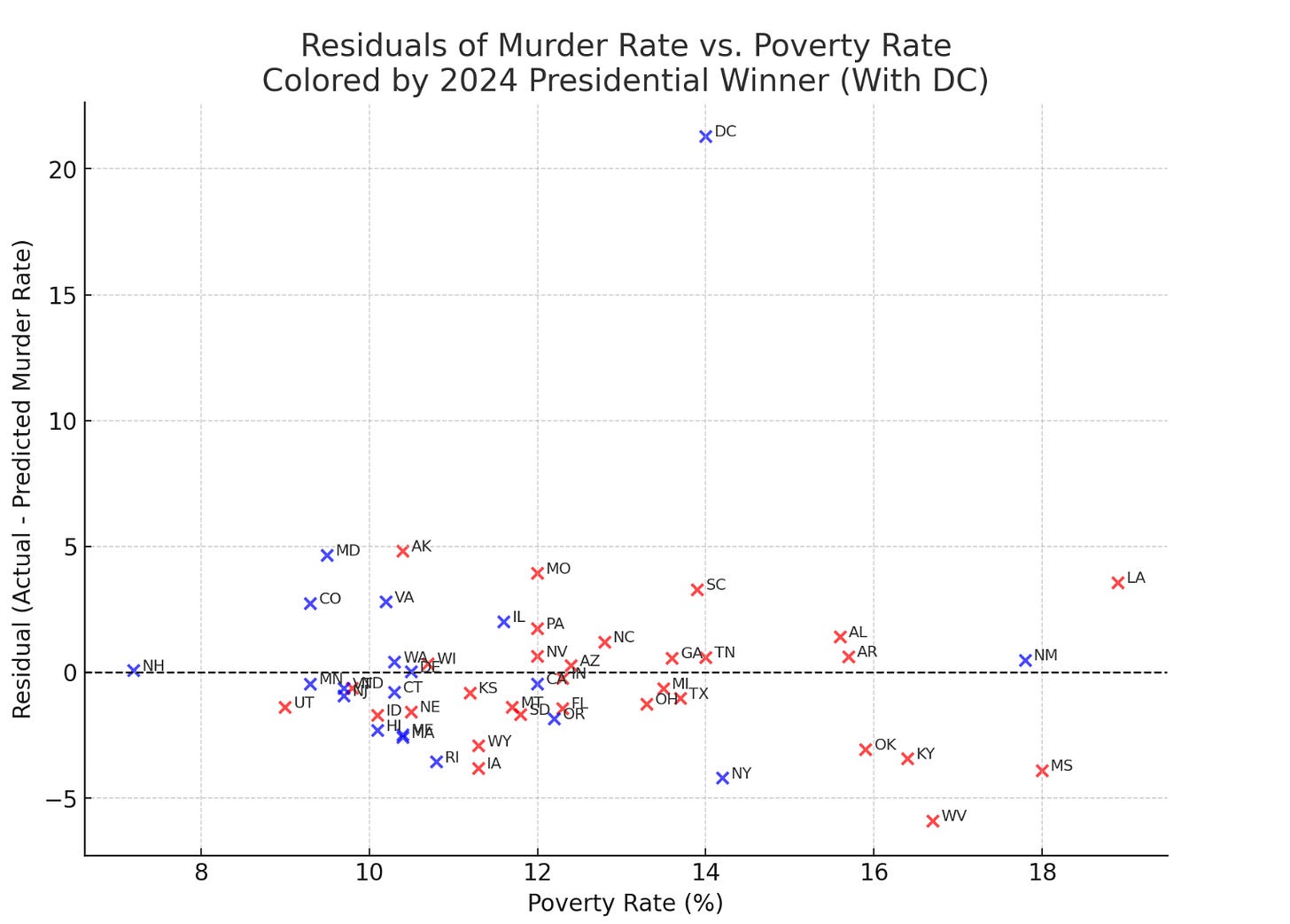

In order to get a grip on partisan differences, we can check out the residual plot. On the x-axis below is again the percentage black. The y-axis is the murder rate minus what you would expect it to be given the percentage black in each state. The way to understand this graph is that states above the line are doing worse than predicted from their black population, while those under are doing better.

The main places that do much worse than predicted are DC, New Mexico, and Alaska, while Mississippi is surprisingly the best performing state when accounting for its black population. Although you might be tempted to chalk this up to Republican governance, the heavily-black and Republican run states of Arkansas and Louisiana are well above the line.

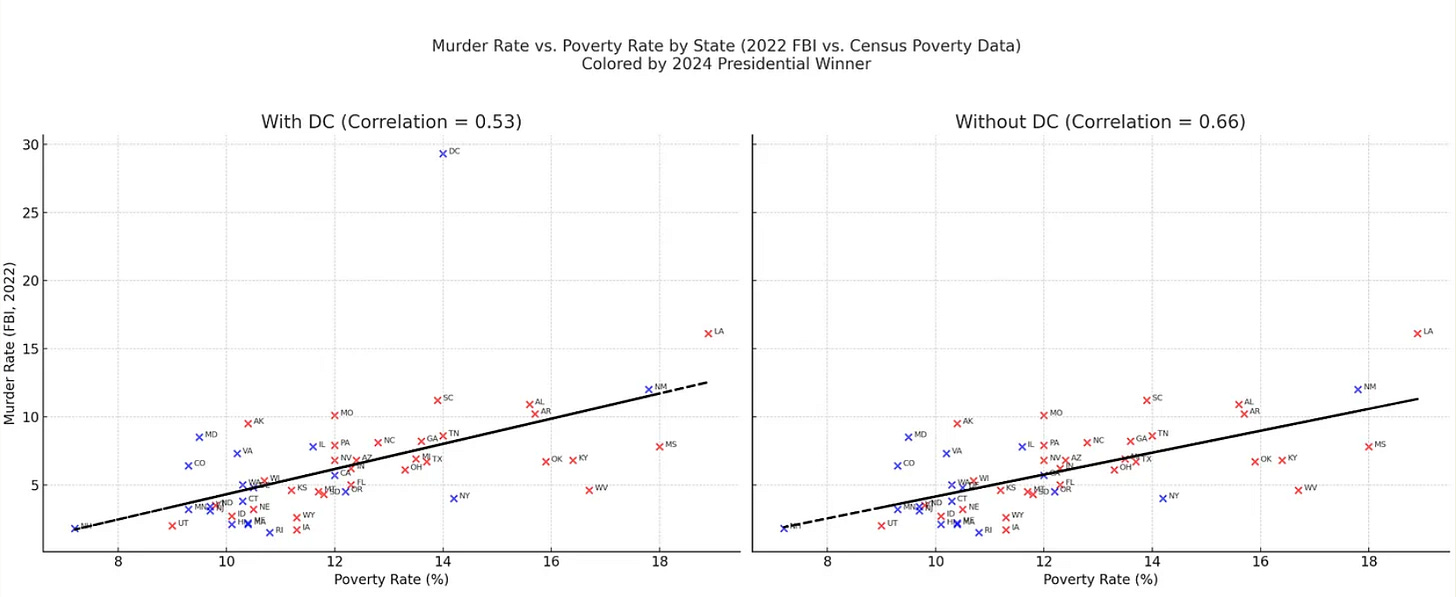

Is percentage black just a proxy for poverty? No, as we know that race has independent predictive power. Below is the poverty rate plotted against the murder rate in each state.

And here is the residual plot.

When you place both poverty and race into a regression, both are statistically significant, but the impact of race is stronger.

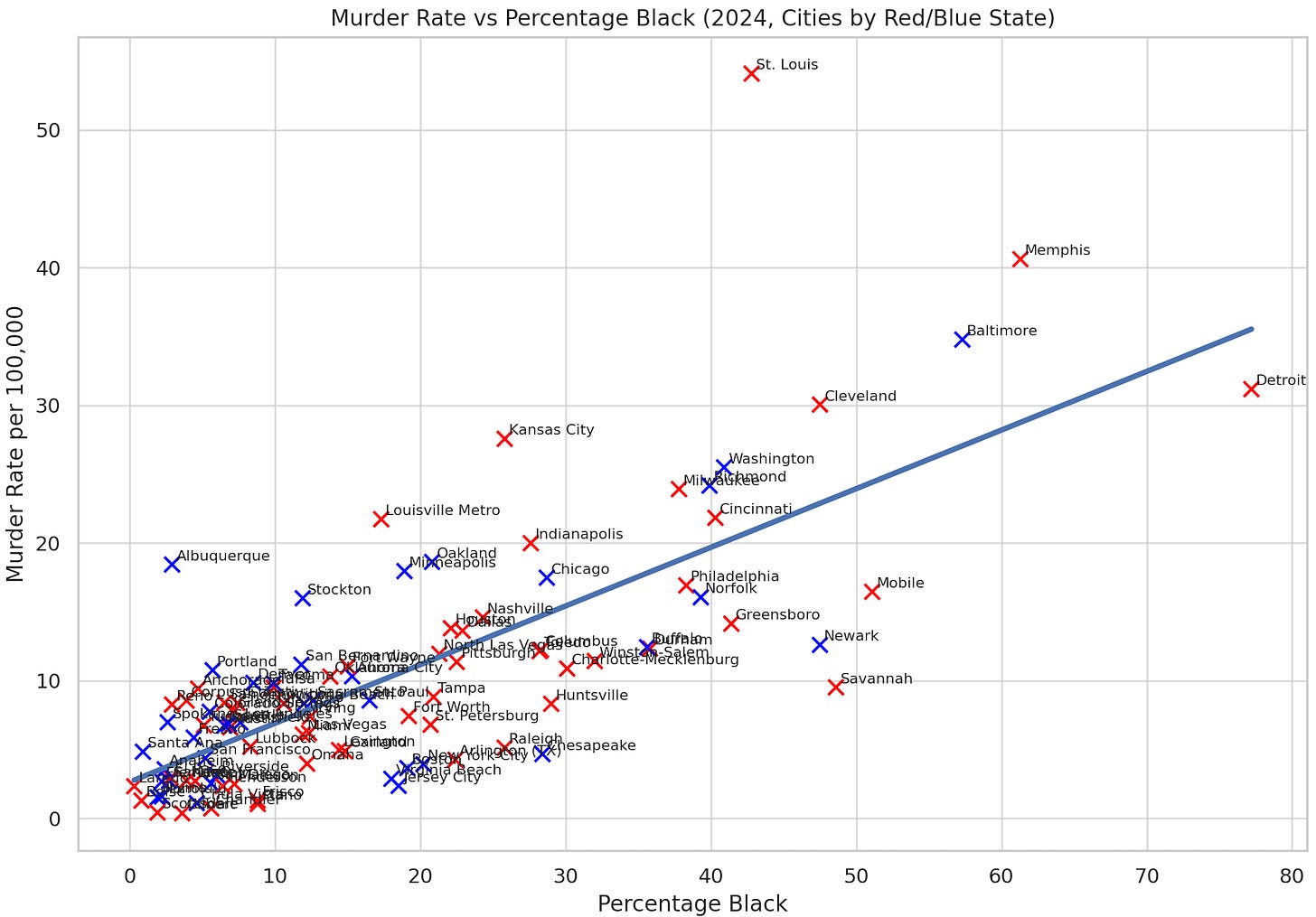

Analyzing states is somewhat crude, and we can get a larger sample size and more precise data by looking at cities. Below is a plot of percentage black against murder rate for the top one hundred most populous cities that reported data to the FBI UCR system in 2024. The murder rates are taken from this Wikipedia page, which also uses FBI data for population numbers. I use the Census Dots website for the percentage of each city that is black. The correlation is 0.78, which is considered near the upper bounds of what you can ever expect in the social sciences

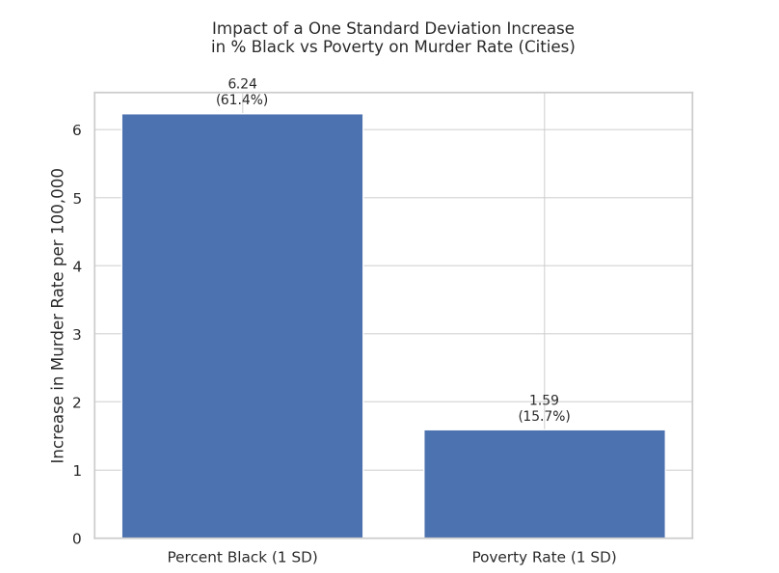

The website Index Mundi lists the poverty rates for the 100 largest cities, taken from the Census Bureau. There wasn’t an exact match between this list and the ones that reported data to the FBI in 2024, so there are only 90 observations that I can match to a city with a murder rate here. When I conduct a regression for cities with both poverty and race as independent variables, percentage black is significant at the p < 0.001 threshold, with a much less impressive p value of 0.04 for poverty rate. A one standard deviation increase in percentage black (15.5 points) raises the predicted murder rate in a city by about 6.2 per 100,000, which is 61% higher than the mean. Meanwhile, a one standard deviation increase in the poverty rate (6.1 points) raises the predicted murder rate by about 1.6 per 100,000, a 16% increase over the mean. Race has about four times the predictive value of poverty. Here is that finding in chart form.

These results are obvious for any American who reads the news or has lived around a major city. We hear stories about gang shootouts in urban black areas, but not in rural communities with a lot of poor white people. When we think of the most dangerous cities in the US, our minds go to places like Chicago and Detroit, rather than Phoenix or Seattle. Statistics simply confirm what makes intuitive sense to any highly informed person living in the United States.

I also conducted a regression with a dummy variable for whether the state where the city was located voted for Trump or Harris, and then another one with a variable for the share of the two-party vote total obtained by Trump in 2024. Thus, we have a model where we dichotomously split states into red and blue, and another where we take into account partisan tilt as a continuous variable. In both cases, partisanship has no impact on murder rates.

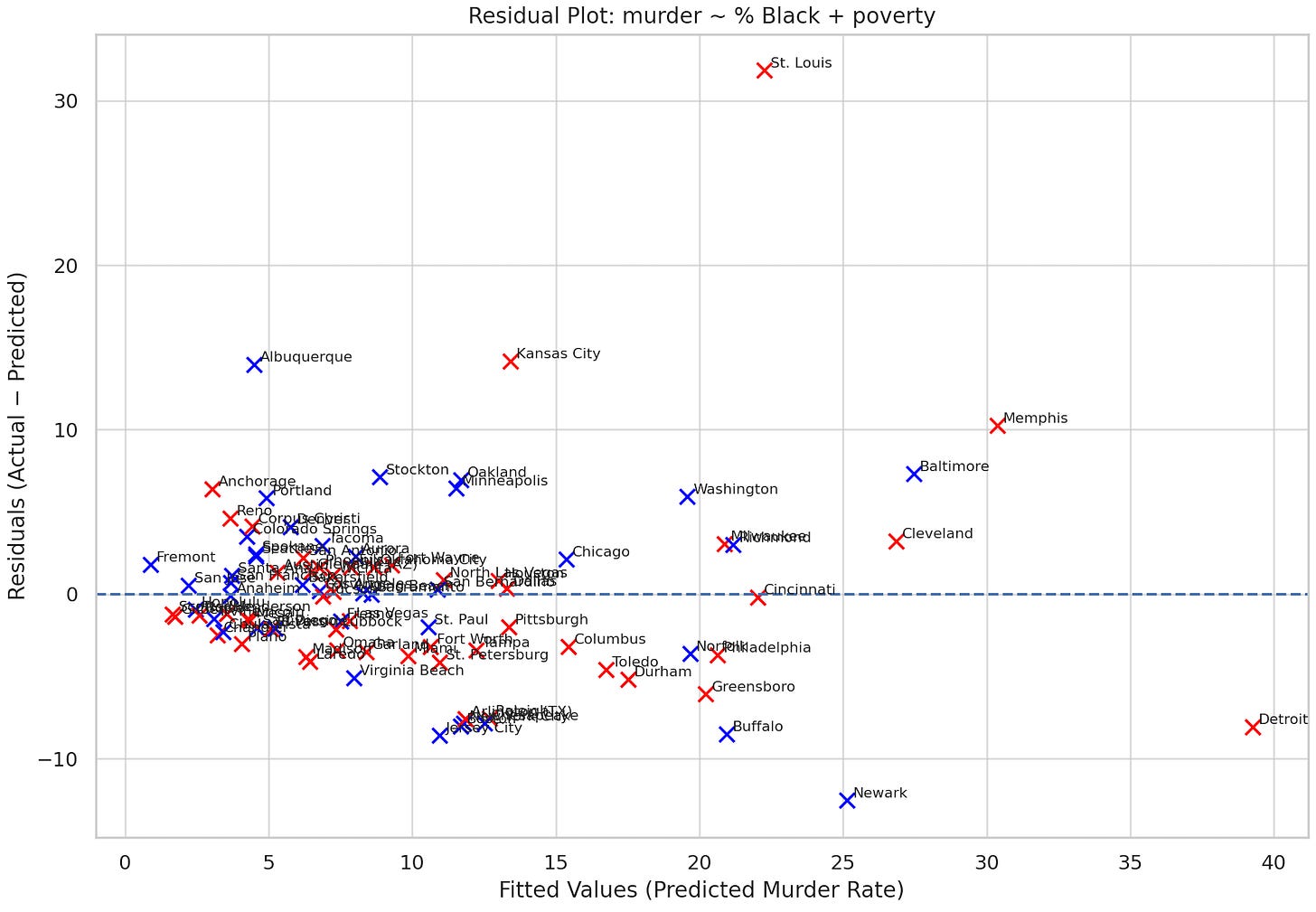

Here’s the residual plot of the model with percentage black and poverty rate as independent variables.

We can visualize the lack of partisan difference here. I wonder what exactly is going on in Missouri, where St Louis and Kansas City are the two cities with the highest residual values, which again, means their murder rate is most above what the model would predict. The two cities with the lowest residuals are Newark and Jersey City, again in the same state. Rounding out the top six best performing cities are Buffalo, Detroit, Boston, and New York City. While there is no red/blue state difference overall, something has gone right in the Northeast. Even Philadelphia, a pretty dangerous place, is relatively safe given how poor and black it is.

You can’t eyeball much of a Hispanic effect. Albuquerque does really poorly, as do to a lesser extent a few West coast cities like Oakland and Stockton. At the same time, the heavily Hispanic cities of San Bernardino, Gilbert, Tucson, Anaheim, Fresno, Mesa, El Paso, Phoenix, Los Angeles, and Las Vegas all cluster around zero, while the residual for San Jose is -5.4. As I’ve said, conservatives are lying about immigrant crime. They’re of course telling the truth about conditions in black cities, and people have trouble keeping these two thoughts in their heads. Hispanics are slightly more criminal than whites, but this shouldn’t be one of your top concerns, given all the policy choices we are free to make that can have a much larger effect on public safety than reducing immigration, especially since such an approach would be disastrous for American living standards. We must also consider the fact immigrants are often the victims of urban crime, serving as a buffer for the rest of the US population.

All of this is to say that there’s no indication that Republicans have any idea how to stop crime. For all their talk of “dangerous blue cities,” Republicans being in power does not noticeably impact the murder rate. I’m not bothering to look at locales with Republican mayors because there are so few among major cities that there’s likely not enough of a sample size to conclude anything. But remember, while cities have control over things like policing strategies, it is state law that determines how crimes are punished and provides the budgets for local governments while setting the rules for how they function.

Besides eyeballing graphs and conducting simple regressions, another way to get at the question of whether Republicans are better at fighting crime is to look at elections that were close, and see whether which party won had an impact on public safety. This is called the regression discontinuity design method, and it is generally superior to comparing observations while controlling for relevant factors, since there is bound to be unseen variation between them. Whether Republicans or Democrats win close elections can be treated as creating something close to randomization. A few papers have done this, and broadly arrived at the same results. Ferreira & Gyourko (2007) find that between 1950 and 2005, cities where Republicans barely won mayoral races did not have crime rates any different from places where Democrats barely won. A paper from this year confirms these results, concluding that there is “no evidence that mayoral partisanship affects police employment or expenditures, police force or leadership demographics, overall crime rates, or numbers of arrests.” The latter study covered the period between 1990 and 2021. This cleared up a misgiving I had about Ferreira & Gyourko, which is that by going back all the way to 1950, they were capturing an era in which there weren’t such extreme partisan differences. Finally, a third paper by Andrew Leigh used a similar design to find Republican governors winning elections had no impact on crime rates, even though they did incarcerate slightly more people.

Republicans Aren’t That Much Tougher on Crime

This result might seem surprising. Surely the party that takes a punitive approach to crime should see less of it compared to the one that sympathizes with violent offenders and worries about racial disparities in arrest rates? Or if you’re a liberal, you might say of course being more sympathetic to people’s material and mental health needs will get them to behave less destructively.

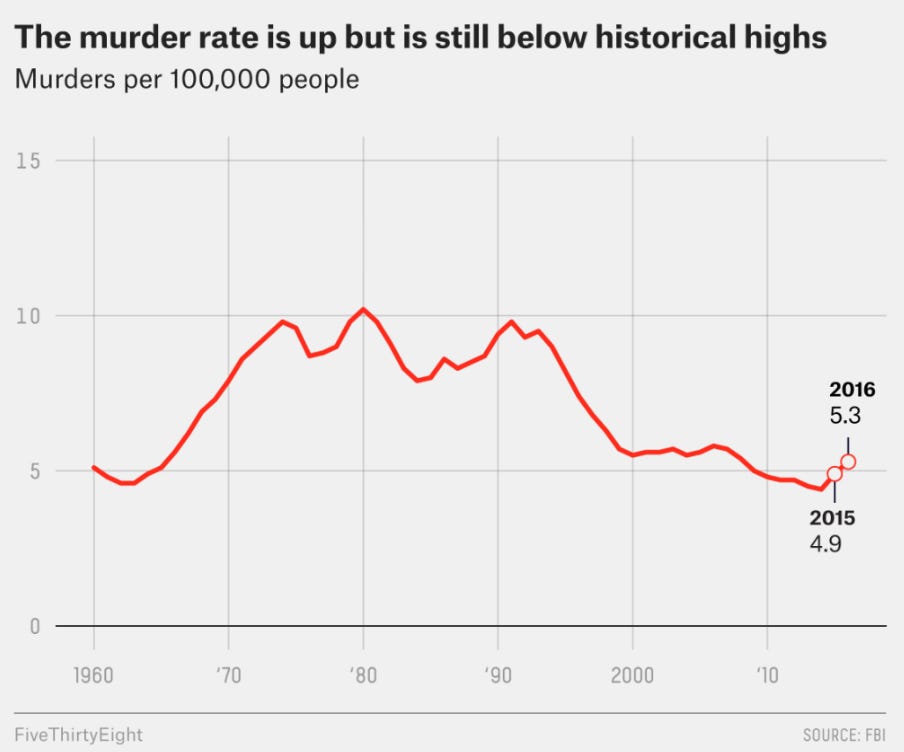

I happen to think that the conservative approach to crime is the correct one. There is little evidence that welfare spending or economic growth reduce crime rates, and a good deal of evidence that a larger police presence and more incarceration do. The US crime rate shot up beginning in the 1960s, during a period when the country was becoming substantially wealthier.

If I were going to guess as to why partisanship doesn’t matter, I would say it’s probably because the policy differences between Republicans and Democrats are quite small. It’s like the situation in El Salvador, where previous governments had tried tough on crime policies, with limited effect, while Bukele’s more extreme approach caused the murder rate to plummet.

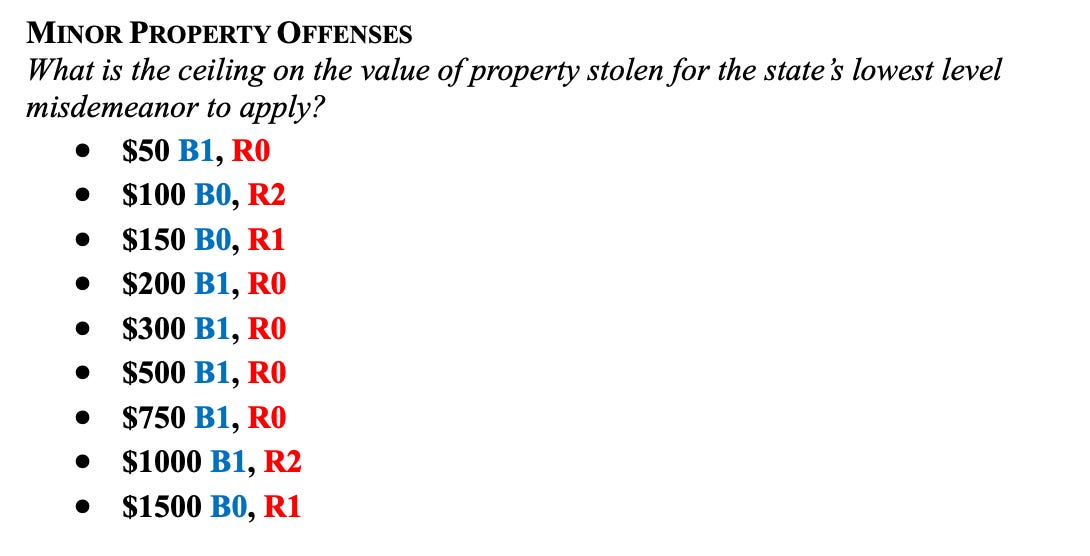

In fact, an analysis from three University of Pennsylvania professors finds few criminal justice policy areas in which six of the reddest and six of the bluest states consistently differ outside of culture war hot button issues like abortion rights and marijuana laws. The authors write that “[o]f the many thousands of issues that must be settled in drafting a criminal code, only a handful – that sliver of criminal law issues that became matters of public political debate, such as those noted above – show a clear red-blue pattern of difference.“ There’s a lot of discussion in the media, for example, about liberal locales letting people get away with stealing more property. Yet there isn’t a clear difference between red and blue states regarding how much you can steal and only face the lowest level misdemeanor charge.

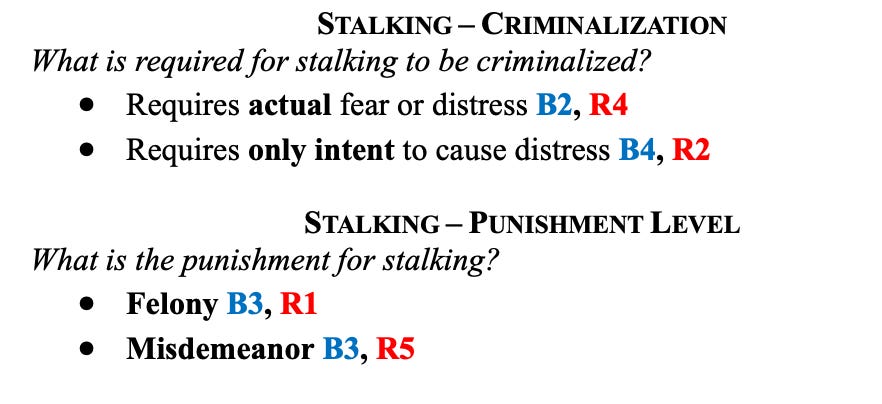

Interestingly, blue states are tougher on stalking, perhaps for MeToo-type reasons.

All six Democratic states have three-strikes laws for habitual offenders, along with five of six Republican states. When it comes to average time served for incarcerated individuals convicted of violent crimes, California, New York, Florida, and Texas are all in the range of 7-8 years. The death penalty is one area where the red/blue divide is clear, but it’s rarely used, and then only after a long process of appeals, so it would be unsurprising to learn that it doesn’t have much of a deterrent effect.

Going back to the Leigh paper above, the impact of Republican governors on the incarceration rate was only 12-13 per 100,000, about a tenth of a standard deviation, and in some models the number wasn’t even statistically significant. The mean incarceration rate in the sample was 216 per 100,000, which indicates that a Republican governor might increase the prison population by about five percent. That may not be enough to matter as far as reducing crime rates. While I believe that incarceration works as a general matter, differences between Republicans and Democrats in this area might not be sufficiently large to have an impact on public safety.

Can We Still Blame the Left?

Despite these findings, I think that there’s still a way to blame the left for high crime rates. While blue states and red states might not differ all that much in their criminal justice policies, that may be in part because all governments are operating under the same limitations on law enforcement and prosecutorial activity shaped by liberal jurisprudence. Consider the following Supreme Court decisions.

Mapp v. Ohio (1961) – Applied the exclusionary rule to the states, barring use of illegally obtained evidence in state trials.

Gideon v. Wainwright (1963) – Required states to provide attorneys to indigent defendants charged with felonies.

Escobedo v. Illinois (1964) – Recognized a suspect’s right to counsel during police interrogation.

Miranda v. Arizona (1966) – Required police to inform suspects of their rights (“Miranda rights”) before custodial interrogation.

Argersinger v. Hamlin (1972) – Extended the right to counsel to misdemeanor cases that could lead to imprisonment.

Furman v. Georgia (1972) – Struck down existing death penalty laws as arbitrary and capricious, effectively halting executions nationwide.

Gregg v. Georgia (1976) – Reinstated the death penalty but with procedural safeguards, reflecting more limits than the pre-Furman regime.

Tennessee v. Garner (1985) – Police can’t use deadly force against a fleeing suspect unless they pose a danger to others.

Beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, courts “discovered” new rights for suspects and criminal defendants. At the exact same time that this happened, the crime rate started shooting up. I don’t think that this is a coincidence.

We take a lot of the procedural rights established in the 1960s and 1970s as sacrosanct, having become part of our collective consciousness through police dramas, but they’re relatively new innovations and in some cases quite odd. Take Miranda Rights. Criminals are very dumb, so as soon as they come across law enforcement, they may start confessing to all kinds of things, intentionally or not. They can’t be compelled to talk, but Miranda forced police to remind them of that fact. Why exactly are we going out of our way to make it harder for criminals to sabotage themselves? Giving defendants a right to counsel throughout the process from the time they are interrogated to the trial likewise introduces friction in the system.

Of course, the justification for decisions like this is that we do not want innocent people to go to jail. But the fact that the Supreme Court started discovering new “rights” in the Constitution at the same time our inner cities began turning into dystopian wastelands should make us consider the possibility that the Warren and Burger Courts did serious damage to American society. The rule laid out in Mapp, where there is a general exclusion on using illegally obtained evidence, is still rare among first world nations. One thing that people should remember is that the more you get the crime rate down, the less you have to worry about individuals being wrongly imprisoned, since there are fewer serious offenses to punish. So a more punitive approach that puts less emphasis on civil liberties may not only work by deterring crime and incapacitating dangerous individuals, but also lead to fewer chances for mistaken convictions through the simple mechanism of the crime rate being lower.

All of this means that no matter how conservative states are, police officers and judges must still operate under rules of constitutional interpretation that moved far to the left in the 1960s and 1970s. In a world where government has to go out of its way to make sure criminals don’t incriminate themselves, everyone gets a lawyer, you can’t shoot criminals who are fleeing, there are strict rules regarding what kind of evidence can be presented against defendants, and the death penalty can only be used rarely and after decades of appeal, it is perhaps unsurprising that red and blue areas don’t differ in crime rates once demographics are accounted for.

One may doubt whether Republican areas would adopt tougher crime policies even if allowed to do so by the courts, given the paper by the Penn professors mentioned above. I think that probably not right away, but eventually you would get more policy drift based on the ideological compositions of states. As mentioned, the problem with a lot of the data comparing states is that ideological sorting has been getting more extreme only in the last few decades. This will take time to show up in criminal statutes, given that legislatures usually don’t overhaul the entire body of state law overnight. If the aforementioned court decisions from previous eras were overturned, I think we would over the years come to see larger gaps between red and blue states in both policies and crime rates, when demographics are accounted for.

A More Serious Crime Agenda

Conservatives spend a lot of energy complaining about the left’s approach to crime. The evidence overwhelmingly suggests that, given the current structures shaping our politics, partisanship has little control over how violent any particular state or locale is. Race and poverty are the main factors determining crime rates, without much room for variations in policy under current conditions to have a large enough impact to be noticeable in the data.

Nonetheless, that doesn’t mean that those who care about public safety cannot do anything productive. A series of decisions by the Warren and Burger courts made it much more difficult to apprehend and punish criminal defendants, and, despite conservatives gaining control over the judiciary, these rulings have continued to go unquestioned. That could change. I’m not sure that allowing cops to shoot fleeing suspects and not giving them lawyers when they are caught would significantly reduce the crime rate. I suspect that it would, and the beauty of federalism is that we can allow different states to take separate approaches and maybe learn something about what works. The Warren and Burger courts, by suddenly discovering new constitutional rights, cut off this process of discovery. The crime rate shot up, and, because Supreme Court rulings apply throughout the country, we cannot know with any certainty the degree to which judges are to blame. Some research suggests that these decisions did have a negative impact, and I hope to dive into this literature at a future date.

In addition to going back to the practices of previous eras, technological surveillance can potentially have a large role in reducing crime. Economist Jennifer Doleac has found that collecting DNA samples from arrestees causes a massive decrease in recidivism rates. Her methodology is very convincing, relying on data from the US and Denmark in which suspects or convicts were added to DNA databases after a certain date. She finds a decline of recidivism by 17% over the next five years in the US, and 42% over one year among Danes. These are huge effects with direct policy implications. Criminals may well be overestimating how much the government having their DNA increases their likelihood of getting caught, but even if so we should take advantage of their lack of sophistication about these things.

All states now collect DNA from individuals in the criminal justice system, but the scope varies: some collect from everyone arrested, others from those charged with certain misdemeanors or felonies, and others only from those convicted —sometimes only of specified serious crimes, other times of all felonies or even select misdemeanors too. There doesn’t appear to be much of a red-blue divide here. Places that only collect DNA from convicts, that is, not from arrestees or suspects, include deep red states like Idaho, West Virginia, and Wyoming, and also Hawaii, Massachusetts, and New York. Doleac’s work implies that all states should collect DNA samples from as many people as possible. This is one of those policies that sounds bad to many people, but it’s hard for me to think of the downsides.

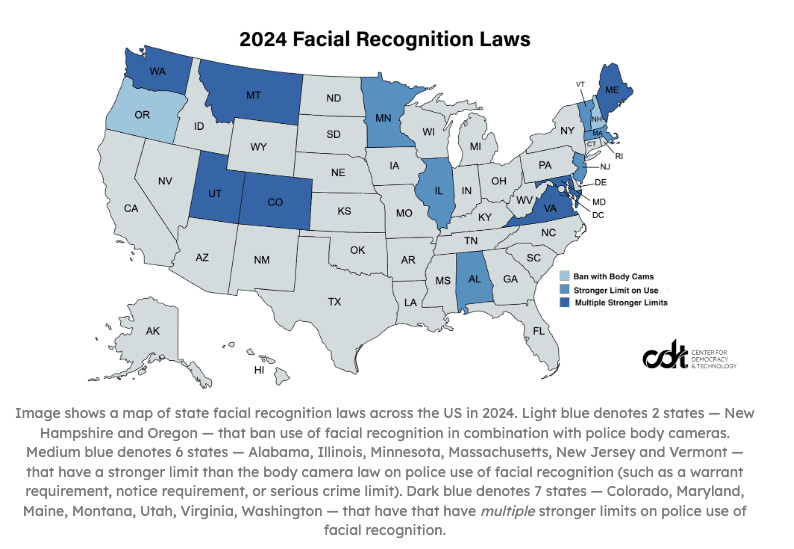

Another new technological development that has crime fighting implications is facial recognition. Left-wing activists complain about privacy violations here, but again, it’s difficult to see what the actual costs are. As with DNA databases, when technology can identify criminals with greater precision and few costs, that is mostly a good thing. Activists sometimes complain that facial recognition isn’t always accurate, which is true, but I haven’t seen anyone show that it is worse than eyewitness identification, which is notoriously flawed, and no one suggests that we stop relying on that. One study found that on average, police agencies deploying facial recognition technology saw a 14% decrease in homicide rates. The debate over shot-spotter – a service that alerts police to gunfire so they can respond quickly – is similar. This is a straightforward crime fighting technology, but attacked on the basis of allegations of racism that make no sense.

As with DNA surveillance, we see no red/blue split on limits on facial recognition technology.

It’s very interesting that while conservatives express much more frustration with crime, Republicans aren’t enthusiastic adopters of the best new methods for keeping their communities safe. The approaches that states take to DNA databases and facial recognition appear to be independent of ideology.

Most of the recurring discussions we have on crime are completely divorced from empirical data. Conservatives seem most interested in blaming minorities and blue cities, while liberals talk about the high rates of violence in red states. It is true that race matters, though that does not have many direct policy implications, not even on immigration, for reasons mentioned above. At the same time, the evidence is overwhelmingly clear that neither Republicans nor Democrats have a clearly superior approach to fighting crime.

As consistent with the entire story of human history, technology has a major role to play in making our lives better. Evidence suggests that DNA databases and facial recognition technology work for preventing crime, and all states should use them more expansively. The “privacy” arguments here are difficult to take seriously, as I have trouble understanding what the concerns even are. A lot of the critiques seem to come from people who just don’t want criminals arrested on principle, perhaps because getting them off the streets contributes to racial disparities. I don’t feel like my privacy is violated if my face can be identified by law enforcement or the government has my DNA, as I have trouble even coming up with a plausible story in which either of these things would have any negative impact on my life. As with privacy in medicine, people are letting implausible theoretical concerns get in the way of adopting policies that can tangibly make society better off.

We should also probably reconsider many of the legal decisions that beginning in the 1960s made the jobs of cops and prosecutors more difficult. There would be costs to such an approach, including the possibility that more innocent people might be arrested or jailed. But the thing about these decisions is that, in many cases, they involve suppressing information that is true. Evidence obtained through illegal means is still evidence, and Miranda rights make it less likely criminals will incriminate themselves, even if they may sometimes confess to things that they didn’t do. Criminals are usually dumb, and society benefits from this fact. The large uptick in crime beginning in the 1960s indicates that there have been serious costs to the rest of us trying to protect them from their own stupidity.

More thoughts. Not only is the influx of drugs omitted from the article, but there's this:

https://capitolweekly.net/the-republican-who-emptied-the-asylums/

"As state hospitals emptied, the number of inmates with diagnosed mental illness incarcerated in jails and prison increased, as did homelessness, to the consternation of Lanterman and his Democratic coauthors, Sens. Nicholas Petris of Oakland, and Alan Short of Stockton."

Mental hospitals were essentially emptied in the 70s, and those people became homeless, addicts, incarcerated, some combination or all three. Drugs and mental illness are a toxic brew, and both issues collided and are correlated with the increase in crime (as well as vagrancy and public disorder). I think both data points should have been included and discussed.

I very much doubt justice-related civil liberties expansion had much effect on crime rates. For one thing, crime rose basically everywhere in this period, at least in Western Europe. England and Canada both introduced their major expansion of suspect's rights in the mid 1980s, for example (Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 and Charter of Rights and Freedoms 1982), after the rise in crime (which occurred there as well) had almost finished- crime started falling not much afterwards.

I think the most boring, prosaic explanation that the 60s/70s rise in crime (and subsequent fall) were largely driven by the post-war baby boom resulting in a lot of young men, is probably basically correct. I still think the lead hypothesis may have some merit, too.