Taking the Medium-Term Past Seriously

The Industrial Revolution, World War II, and forecasting the future

In a recent podcast, Tyler Cowen and Peter Thiel debated whether we are heading towards some great discontinuity or society might simply muddle along.

COWEN: Let’s say you’re trying to track the probability that the Western world and its allies somehow muddle through, and just keep on muddling through. What variable or variables do you look at to try to track or estimate that? What do you watch?

THIEL: Well, I don’t think it’s a really empirical question. If you could convince me that it was empirical, and you’d say, “These are the variables we should pay attention to” — if I agreed with that frame, you’ve already won half the argument. It’d be like variables . . . Well, the sun has risen and set every day, so it’ll probably keep doing that, so we shouldn’t worry. Or the planet has always muddled through, so Greta’s wrong, and we shouldn’t really pay attention to her. I’m sympathetic to not paying attention to her, but I don’t think this is a great argument.

Of course, if we think about the globalization project of the post–Cold War period where, in some sense, globalization just happens, there’s going to be more movement of goods and people and ideas and money, and we’re going to become this more peaceful, better-integrated world. You don’t need to sweat the details. We’re just going to muddle through.

Then, in my telling, there were a lot of things around that story that went very haywire. One simple version is, the US-China thing hasn’t quite worked the way Fukuyama and all these people envisioned it back in 1989. I think one could have figured this out much earlier if we had not been told, “You’re just going to muddle through.” The alarm bells would’ve gone off much sooner.

Maybe globalization is leading towards a neoliberal paradise. Maybe it’s leading to the totalitarian state of the Antichrist. Let’s say it’s not a very empirical argument, but if someone like you didn’t ask questions about muddling through, I’d be so much — like an optimistic boomer libertarian like you stop asking questions about muddling through, I’d be so much more assured, so much more hopeful.

Listening to this passage, I got the impression that Peter really doesn’t like the idea of muddling through on aesthetic grounds. What this debate gets at is that some of the most fundamental questions we face in trying to forecast events relate to which base rates to pay attention to, if any. Let’s say you want to know whether the next US president will see articles of impeachment filed against him. One person might say that the vast majority of American presidents have not faced articles of impeachment, so the probability is low. Another argues that this is the wrong way to look at things, since it has happened to 6 of the last 8 men to hold the office. Is the correct base rate all American presidents, or just those of the last two generations? Another person might say that both these perspectives are wrong, and that Trump has completely transformed our politics, so you have to take that into account.

We must to a certain extent rely on the past to predict the future, but in doing so we face an endless number of judgment calls regarding how to understand and conceptualize the past. In a broad sense, I’ve noticed that there are three kinds of analysts, mapping on to the ways of thinking about the likelihood of impeachment articles listed above.

First, there are those who look to all of human history as a guide. They notice that our species has seen civil wars, civilizational collapse, famine, and technological regress disturbingly often. Why can’t we expect these things to happen again? I never get tired of using Peter Turchin as an example of a person who is bad at thinking, so I’ll do so again here. Some years ago, I read 1177 BC by Eric Cline, which is about the collapse of the Bronze Age. I enjoyed the history, but the author put forth a tortured attempt to make his research relevant to today by pointing out similarities to the world of three millennia ago. The argument was something along the lines of they had global trade and geopolitical tensions, just like we do, so isn’t that spooky? It was an extremely dumb argument and almost turned me off reading the whole thing, but I understand why he did this. A book that claims to use history to provide insight into our current condition is likely to sell more than one that simply tells you about things that happened in the past that have no modern relevance. In 2021, I wrote a critique of Graham Allison’s argument that a database of great power relations going back to the 15th century can tell us anything about the US-China rivalry today. More recently, Eli Dourado has an essay trying to glean insights from previous civilizational collapses in order to understand modern society, although he does a better job than others of pointing out that a lot has changed since the Mayans.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, there are those who imply that the past has nothing to teach us about the future. The clearest example of this is individuals who believe in the massive capabilities of coming AI, whether doomers or e/acc types. Humans have enjoyed a long run as the most intelligent life form on this planet, but those days are coming to an end. Instead of continuing to be the masters of our destiny, we’re about to find ourselves in the position of horses or apes, if not ants. The Bronze Age is useless for forecasting the future, but so are the 2010s.

There is a third approach that is usually more implicit, rarely dwelled upon because the story it tells is arguably less exciting. Nonetheless, it is I believe the correct one. People who compare the present to the distant past are taking too broad of a perspective, while those who want to ditch the study of history completely are also making a mistake. For the best forecasts, you should be taking the medium-term past more seriously than most analysts do.

Under this view, technological, political, and moral progress are real, and deserve to be taken seriously. Sure, civil war has been common throughout history, but there have been many prosperous democracies since 1945, and not a single one has experienced large scale internal conflict. This fact is likely to be more relevant than anything that happened in Ancient Rome or even the late Ottoman Empire. This is true even if we can’t put our finger on exactly what the most important changes have been — there are too many candidates to consider and no way to conduct experiments to adjudicate between them. It may have been possible for civilizations to collapse and important technologies to have been forgotten in the ancient world, but it’s difficult to see how that would happen in an era of mass produced books, television, and the internet. As important as Ancient Rome was, probably the majority of people alive during its existence had never even heard of it. Today, travel, widespread or universal literacy across most of the globe, and worldwide instantaneous communication ensure that knowledge that is truly valuable is rarely forgotten. If one country rejects a crucial or essential aspect of modernity for contingent political or social reasons, the rest of the world will know about it and be able to observe what is happening.

At the same time, one shouldn’t toss away the past completely. As Robin Hanson points out in his critique of AI doomerism, most technologies and developments cause incremental change at most. I use ChatGPT in my daily life, but I think that when the latest models came out we all got a bit too excited. Yes, it’s pretty cool that I can conduct data analysis and make graphs and figures in a fraction of the time it took before. It’s of similar magnitude to Excel or Google, not something that I think is going to turn us into paperclips. While questions about whether we can actually control a superhuman AI might be interesting, I’ve become less patient with those who use the concept of exponential growth to promise us that such a technology is right around the corner. Of course, hinge points do not have to be technological, as they can also be political or social. But the last few years have seen the downfall of serious ideological challenges to liberal democracy and I judge the probability of another world war to shake things up to be low.

Taking the medium-term seriously means understanding that there are singularity-type events that ensure that the old rules no longer apply. At the same time, they are very rare, maybe one every few centuries or so. The Russian-Ukraine War and 9/11 are certainly going to be part of any comprehensive history of the twenty-first century, but may not make it into a short book on the third millennium. Most events, whether geopolitical shocks or new technologies, don’t fundamentally change things all that much because the world is in a state of rough equilibrium, with most fundamental transformations being dependent on gradual trends, like population shifts or a changing climate. Certain technological capabilities increase exponentially, while we make very little progress at all and in many ways go backwards when it comes to governance, as we can see in how difficult it is to build new infrastructure and the fact that we see more urban crime and disorder than we did in the 1950s.

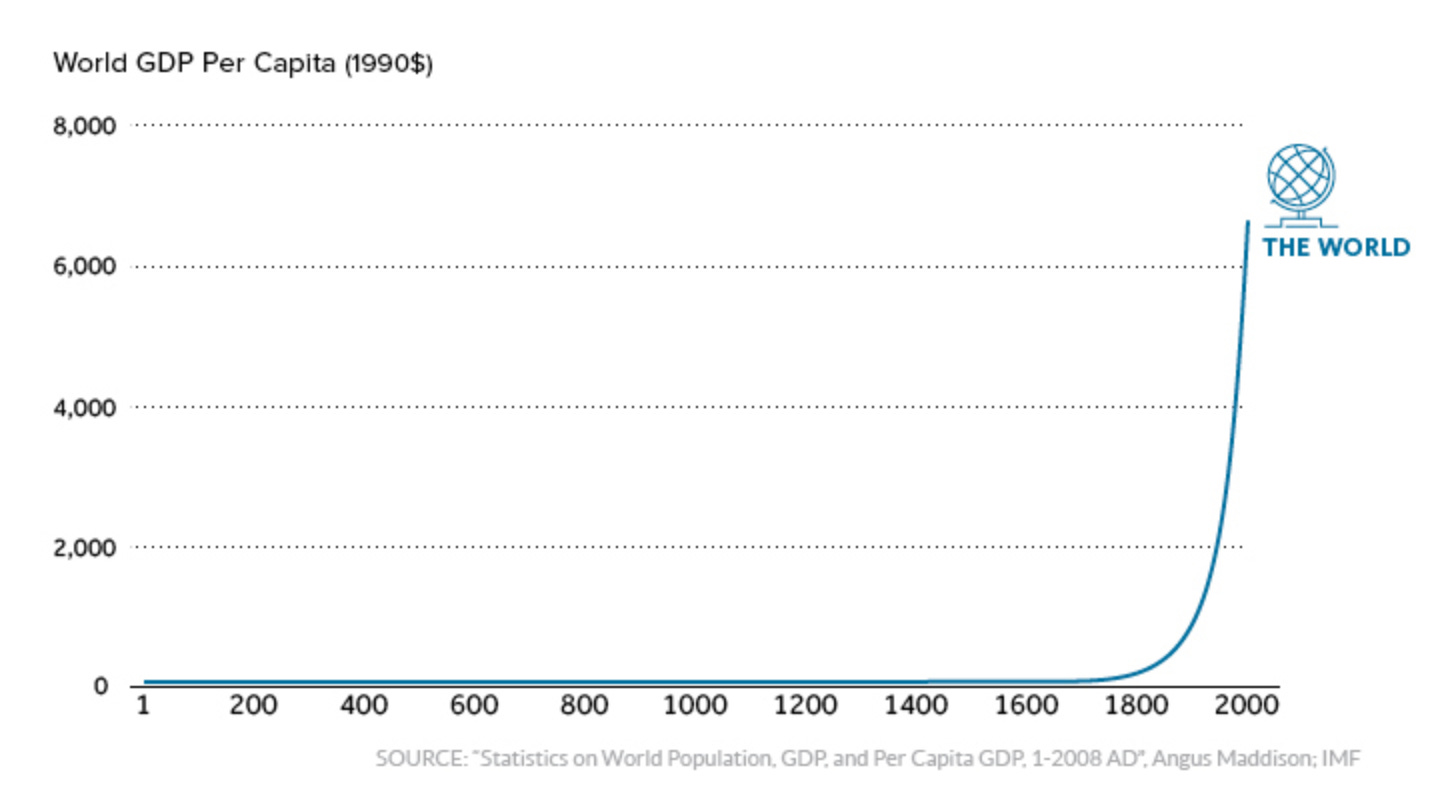

In our current age, I think that the two main phenomena that should be guiding how we think about the future are the Industrial Revolution and World War II. On the first of these, here is neoliberals’ favorite chart of all time.

From a broad historical perspective, when it comes to human living standards basically nothing at all happened until the eighteenth century, and since then progress has been quite continuous. Sure, there have been booms and busts, and economic growth has slowed quite a bit from its peak in the early-to-mid twentieth century. But what’s important to realize is that we’ve had roughly nonstop growth for two and a half centuries now. There doesn’t appear to be any consensus among economic historians as to how this process got started, but it’s easier to understand why once we got rich enough it was unlikely that we would go backwards. Production techniques and industrial knowhow are much less likely to be lost than before once you’ve crossed thresholds like mass literacy, computational power that can store large amounts of information, and the ability of people in any part of the world to communicate instantaneously.

In terms of politics, there has been historical learning, and though we’ve seen that liberal democracy has a great many problems, the best argument for it is still the failures of every other system. Sometimes things do get worse in certain regions and areas of life, like with, for example, the increase in violence in Latin America over the last few decades. But institutional variation and knowledge about what is happening elsewhere in the world means that a Bukele might come along and show a different way forward. We collect statistics and have a global media, so the successes and failures of different societies become clear to others. There is of course a great deal of bias and noise amidst the signals we receive about what works and what doesn’t, but enough truth gets through to allow for course corrections. If Bukele actually ends up permanently solving crime in El Salvador, the rest of us will know about it. This process of global communication and learning explains why the Soviet Union collapsed. Had there been no capitalist world to look to for inspiration, or no way to learn about it, it is difficult to see how the people of the communist bloc could have imagined a different future.

If the Industrial Revolution permanently changed the technological context in which societies operate, World War II created new political realities. If you read Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature and look at the graphs throughout the book, you notice that something fundamentally shifted in 1945. It’s hard to differentiate between the effects of the end of World War II and the invention of nuclear weapons because these two things inconveniently happened in the same year. But I tend to think the American-led order set in the postwar years as described in John Ikenberry’s After Victory is a better explanation of the course the world has taken. A kind of paradox of the taboo on nuclear weapons use is that I think it’s worked so well that nukes have almost become irrelevant. The two major wars that have gripped the world’s attention in the last few years, Gaza and Ukraine, involve a state with nuclear weapons fighting an enemy without them, but no one seriously thinks they’re going to be used. Russian nukes may make the US think twice before escalating, but even if they didn’t exist I don’t imagine that we would ever fight a land war over Ukraine anyway.

Oona Hathaway and Scott Shapiro in The Internationalists put forth a bold thesis, arguing that it was the much-maligned Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928, which supposedly “outlawed war,” that created new international norms, as the border changes that occurred through military force after that time tended to get reversed. Yet, as the authors acknowledge, it would be wrong to argue that norms like this would have been just as likely to have been enforced had the other side won the Second World War. Of course, World War II, like the Industrial Revolution, can be considered as a number of discrete events, or even part of a larger story, as when historians sometimes talk about the great European civil war fought in the first half of the twentieth century. But the point is that for the purposes of understanding our current circumstances, I think the best framework involves taking seriously the argument that we are still living in the shadows of the Industrial Revolution and World War II.

What are the implications of this? First, you should be bullish on economic growth into the foreseeable future. Life will incrementally improve for most people living in most places. Between 1950 and 2016, only nine countries in the world got poorer and most ended up much richer. It’s of course worth noting that of those nine countries, seven are in subsaharan Africa, and another one is Haiti, composed almost exclusively of people of black descent. Since this has the highest birth rate of any region, that might be a reason for concern, as the world becomes Africanized. Nonetheless, Africans will still only be 25% of the world by 2050, and I would expect fertility between them and those who live in other regions to narrow. Changing global demographics are a long-term concern, say on the order of 100 years, but in the meantime I expect most of the non-African world to continue seeing life get better, and even most of Africa too. The world may at some point become so African and Muslim that the old rules no longer apply, which would be one of those gradual long-term shifts that can’t be traced to a single distinct event but ended up changing the world, in the way that the United States was populated through natural growth among European settlers.

I think that some level of economic growth is practically automatic at this point. Even the Soviet Union got wealthier under communism, which means it’s almost impossible to screw this up. In fact, economics textbooks used to predict that it would eventually surpass the West, even though they overestimated Soviet progress, likely due to ideological bias. While rates of growth can vary based on human capital, policy decisions, and institutional quality, you have to get a lot wrong in order to go backwards in the era of global communication and widespread knowledge of technology and what makes for more successful societies.

In contrast to the direction of economic growth, the decline of war has been more contingent. I think that civil war within advanced societies is practically impossible today. But October 7, along with Putin’s attack on Ukraine, imply that dictators and fanatical movements will still make war when the opportunity presents itself and they are ideologically driven to do so. American leadership here is therefore very important, as it is the only nation that can be the focal point of a liberal democratic alliance. So I’d predict no civil wars in developed countries, and global order to prevail only if the US stays committed to continuing its leadership role.

A world of consistent, but not stratospheric, growth, is far from a dystopia. Two percent growth a year leads to a doubling in living standards over 35 years. But 4% gets you to the same place in less than 18. If you have children today, that’s an important difference for their future quality of life.1 We should definitely all argue and fight for the economic policies that get us closer to 4% than 2%. In practice, the world of 2100 will look very different from that of 2024, just as how our own era looks different from the 1950s, even if we unfortunately never colonized space. Quantity has a quality all its own, and even 2% growth in the long run is enough to lead to dizzying amounts of change, even from the perspective of one lifetime.

At the same time, I think that the confidence intervals of what is going to happen geopolitically are a lot wider. If in economics, 2-4% growth a year is the range of outcomes we can expect, then in geopolitics the possible outcomes range from nuclear war to world peace. And while I think that we know what is conducive to faster economic growth, and achieving it requires only the political will to overcome special interests and bad ideas, in geopolitics there is a great deal more uncertainty and need for careful thought regarding what the ideal policies are.

One thing that neither World War II nor the Industrial Revolution has settled, or even necessarily placed on the right track, is violence in the developing world. Much of Latin America is ravaged by crime, while Africa and the Middle East are in many places suffering from civil war. Unlike economic growth, the trend hasn’t been moving in the right direction, or at least not consistently enough and on a long enough time scale for us to be confident of what’s going to happen in the future. According to Our World in Data, among Central and South American countries for which we have numbers, most had a higher murder rate in 2020 than 1990. Across the globe, more than twice as many people died in civil wars in 2022 than 1989, which is a faster rate of growth than that of the world population. Of course, as already discussed, these deaths have practically all been in poorer countries, which indicates that once your society reaches a certain level of economic and sociopolitical development, you’re pretty much in the clear. It’s just getting there that is the problem.

To summarize, here are my medium-termist predictions regarding what will happen in the course of say the next 50-100 years.

Economic growth at 2-4% across the developed world.

Political and economic stability in developed countries.

More chaos, death and destruction in the third world, with things having the potential to get either much better or worse. I’m bullish on Latin America and South Asia and bearish on the Middle East and Africa.

Geopolitical stability if the US continues to play its historic role as the guarantor of the world order, and no I don’t mean in the European sense of becoming a “humanitarian superpower” by helping Hamas win, but rather punishing terrorism and interstate aggression. This will require in many cases tossing aside human rights norms, which to a large extent now work to the advantage of global actors we don’t want to have power.

These predictions may seem a bit boring. People seem to enjoy fantasies like us devolving into a kind of Mad Max dystopia, or alternatively heralding the creation of machine-Gods. I don’t think that the world will be that exciting in the future, but we can still have a lot of fun cheering for the triumph of Israel over Hamas, and defeating the statists who want to push us closer to the lower end of growth forecasts.

Let me note here that I don’t want to give the impression that I take GDP growth numbers that literally. As Diane Coyle points out in her book on the topic, there is a lot of subjectivity and uncertainty that goes into this metric. Consider terms like “2% growth” and “4% growth” to roughly correspond to “living standards get better slowly” and “living standards get better faster than that.”

It's odd to take the world since the industrial revolution and since WW2 as your baseline but not to think that events like them could happen again.

The industrial revolution raised the global growth rate from 0.1% to 2%, why couldn't AI rise it from 2% to 40%?

If WW2 can happen, why not WW3?

"there have been many prosperous democracies since 1945, and not a single one has experienced large scale internal conflict."

Huh? Argentina was a very prosperous democracy. Chile too. That's just off the top of my head.