I enjoyed Lyman Stone’s article arguing that pro-natalists should be more open about their views, and also more judgmental about the choices people make in their lives. His argument is basically that among more sophisticated pro-natalists the tone taken is something along the lines of this:

Fertility is decreasing and that may cause a few societal issues. If you don’t want to have kids, that’s totally fine! We definitely don’t want you to feel pressured or judged in any way. But since people want more children than they’re having, maybe we should consider these small policy tweaks to make that more likely.

There are a lot of problems with this. First of all, as Lyman points out, it’s dishonest. The people who prioritize getting the birth rate up think it’s a good thing to have more kids. By necessity, this means that it is a bad thing to have no or few children. You can’t fool people on this point.

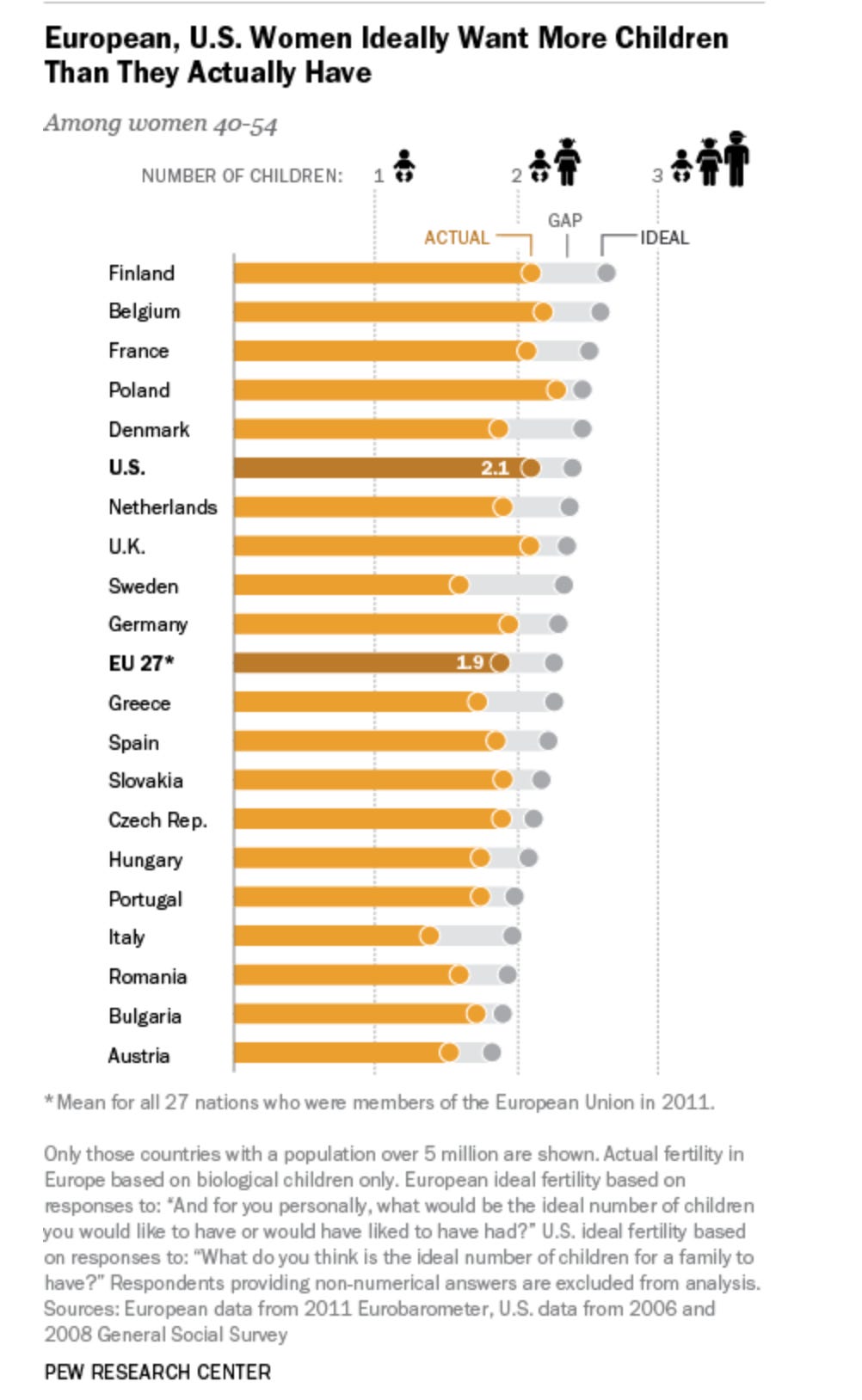

I would add that the “people are having fewer children than they want” argument is extremely weak. You will often see citations to charts like this.

I’m guessing that when you ask women this question, they’re thinking about an ideal scenario without tradeoffs. But there are always tradeoffs between having children and doing other things, and we should take actual behavior as closer to reflecting true preferences. The question “What would you do if you had no financial constraints and total freedom?” doesn’t tell us much about how individuals are likely to act under any real world conditions. As a purely financial matter, people in advanced countries are much more capable of having their desired number of children than anyone else in history. We have to acknowledge that they’ve chosen to have many fewer than is socially optimal and this is despite the relative ease with which they can create families today.

Anyway, Lyman has inspired me to write the piece I’ve been thinking about for a while, which is to explain why I am a pro-natalist. One reason I’ve hesitated is that those who care a lot about this issue are the kinds of people I find extremely unappealing. If you look at last year’s Natal conference, many of the attendees and featured guests are prone to white nationalism, spreading fake news, MAGA cultism, anti-vaxx, Based Ritualness, and overall rightoidism. There were also many attendees I respect. One of them, Bryan Caplan, wrote about his experience there:

The four speakers at the opening dinner were, to be blunt, embarrassingly bad. Classicist Alex Petkas was extremely smart and articulate, but his talk about Spartan mating customs was bizarrely irrelevant to modern fertility issues. He probably freaked out more than a few attendees. Influencer Jack Posobiec was paranoid, rambling, and misanthropic. He barely even mentioned fertility; indeed, there was no sign the man even liked children. Hanania says that Posobiec is a confessed liar, but insincerity would honestly be an improvement. Terry Schilling of the American Principles Project was temperate by comparison, but offered no coherent arguments.

People like this are a psychological barrier to me being as enthusiastically pro-natalist as I should. And when I find myself holding a view that I share primarily with evil and stupid people, it rationally gives me pause. At the very least, by advocating for such a cause, I may make it more likely that these types of people could gain power, which would itself be a reason not to support the cause in the first place. Some people clearly just like pro-natalism as an ideology because it provides an excuse to tell people what to do, primarily women.

But the future of humanity is too important to say our species should die out because Jack Posobiec would prefer that it didn’t, as tempting as that argument might be.

So here I’m going to tell you why I am a pro-natalist. I’ll then go on to explain how I think we should think about the fertility issue in terms of public policy and culture.

Utilitarianism and Virtue

The utilitarian case for pro-natalism is straightforward. More people is good. A world of ten billion humans is better than five, holding quality of life constant. This raises the problem of the repugnant conclusion, put forth by Derek Parfit. If more life is good, why not advocate for a world where people spend all their time creating more children up until the point where the life of each person is barely worth living?

To me, this problem has a simple solution. Having kids is hard, and I don’t think a world where women are spending all their time focusing on reproduction creates lives that are positive net value. There are increasing opportunity costs to each child, along with diminishing returns in terms of how many resources you can invest in them and even the time you can take to enjoy them. What is the ideal fertility rate for a society? I don’t know, but would guess somewhere between 4 and 8 per woman. I think 15 is definitely too many, and 2 is too few. Perhaps a fertility rate of 6.5 is ideal from a utilitarian perspective. It should be said that my standard for “life not worth living” is lower than that of a lot of people, which is why I’m a huge euthanasia fan, and this goes a long way towards helping avoid the repugnant conclusion even without taking into account non-utilitarian considerations. If you think I’m wrong on this specific point, I still think you can reject the repugnant conclusion by arguing that even if the number of utils in the world would be maximized by trying to maximize fertility, there are non-utilitarian considerations of human flourishing that we should take into account. That said, if you’re a pure utilitarian and you also believe that even the worst human lives are positive net value, you should then just bite the bullet and support the repugnant conclusion. That is, unless you’re a pure utilitarian who also cares about animal suffering, in which case there’s probably a good argument for trying to end the world. But that’s an essay for a different time.

Of course, we also have to factor in that for the most part, a growing population under non-Malthusian conditions is a good thing even in terms of average utilitarianism. Technological innovation is the ultimate driver of improving living standards, and more people equals more innovation, all else equal. On this point, I recommend Julian Simon’s 1981 The Ultimate Resource, which I would argue has in essence predicted the nearly half-century since it was written, during which we’ve seen very little in the world to indicate resource constraints on growth, and confirmation that getting political and policy decisions right are what matter.

People sometimes make the mistake of believing that all innovation has to come from geniuses, but this is wrong. Throughout history, manual laborers, farmers, and other ordinary people have just stumbled upon new ways of doing things in the course of their jobs. Examples of this can be found in Brian Potter’s The Origins of Efficiency, among these being the nineteenth century British textile worker who reportedly figured out how to use a piece of chalk to make sure his thread didn’t break, and then received a pint of beer every day from his employer in exchange for revealing his secret. Progress depends on small innovations building upon one another, up to the point that an entirely new technology for doing the same thing becomes cost-efficient and the old discoveries can be discarded.

Rather than requiring genius, many innovations are serendipitous and come from direct hands-on experience in a profession. Also, a higher population and more population density make it more cost-effective on a per person basis to provide law enforcement, education, sewage, and regular goods and services. More people within a particular economic zone creates larger markets that allow for more specialization of labor. Of course, there must be some limits to this principle, as if we all stopped working and just had as many kids as possible, the economy would suffer. But there’s every reason to believe that most people on average would be much better off in advanced countries if they had much larger populations.

In this sense, there’s a straightforward connection between being a pro-natalist and being pro-immigration, since in each case you’re understanding the overwhelming benefits of population maxing. But, as we all know, the people who talk most about the need for more babies, like JD Vance and most of the types who attend the Natal conference, tend to favor lower immigration, which is how you know their intentions are evil. They adopt zero-sum economic thinking on immigrants and jobs, but don’t follow their own logic when it comes to natives. Nearly all worldviews have some forms of cognitive dissonance, but “pro-natalism, anti-immigration” is a particularly extreme case, so it logically appeals to people who are bad at thinking and full of hate.

Lurking in the background is sometimes a concern with population quality, which is a more rational argument than zero-sum economics. The idea is that immigrants, or at least some immigrants, are more prone towards criminality and welfare dependency. I doubt this is the real motivation for the most aggressive nativists, since many of them also hate high skill immigration, when their own logic suggests they should be enthusiastic backers of it. We can at least give the benefit of the doubt to those who only oppose low-skilled migrants and say that many of their concerns are not completely imaginary or irrational. I think they still underestimate the power of simple population-maxing in most cases. Regardless, these are mostly good arguments to figure out how to fight crime and shrink the welfare state, since those are the mechanisms through which human beings harm others in modern societies. I don’t think the idea that immigration makes these issues more challenging to fix should be taken all that seriously, since higher order political outcomes are extremely hard to predict, and if you care about implementing policy X, the best thing to do is fight on that issue, rather than try to engage in demographic engineering and hope you get X as a byproduct. With all the uncertainty in the world, more indirect methods of getting to a policy outcome are generally not a good use of time, and in cases where people are trying to engage in demographic engineering for such purposes, their plans usually rely on overly simplistic models of the connections between the backgrounds of individuals, their views, and political outcomes.

In addition to the straightforward utilitarian argument, I believe that having children is virtuous. There are some things you should just do because you should want to be the kind of person who does them. As I’ve previously written:

Upon more reflection, perhaps we can say the real reason I had children and hope to have more is that it fits into larger narratives I am committed to about the world and my place in it. It is sort of like not littering. I get mad when I see other people throw garbage on the ground and tend to confront them. An effective altruist might argue that this is a waste of time, and instead of paying attention to who around me is littering I could do more by donating money to whatever organization does the best job of tackling the problem. This line of thought might lead to the conclusion that I shouldn’t even bother to refrain from littering myself since doing so doesn’t really add much to the problem. But it feels wrong to approach a societal issue in this way.

Leftists are often criticized for virtue signalling, which involves favoring largely pointless gestures instead of taking more substantive steps to address the problems that they supposedly care about. Perhaps that is what I’m doing when I yell at a litterer. But what is called virtue signalling in many cases can be thought of as making sure there is alignment between what one believes and how he behaves in his own life, which might be taken as one of the definitions of virtue itself.

People need something to believe in. I think society has gotten worse and the discourse much dumber since more and more people have sought to find meaning through politics. Having a family cures people of nihilism and despair. Many modern problems faced by the young aren’t the result of economic challenges, but life being too easy. I’ve known junkies who’ve gone deep into their twenties never having worked a job, instead sponging off their parents their whole lives. This would be impossible without their families as enablers, and we’ve reached a point in society where enough capital has been built up that even middle class people can indefinitely support their kids as adults in their childhood bedrooms. This has been a negative consequence of getting wealthier, and promoting marriage and having kids as a goal can help solve these types of more existential issues.

Pro-natalism also coheres with other values I hold dear. I believe in vitality. We should have a culture that is appreciative of its past, optimistic about the future, and willing to sacrifice for the good of the species. People should believe that there is much more to life than being safe and comfortable. Having kids is the ultimate statement that life is not merely something we should try to survive, but worth affirming and extending into the future.

Policy Implications and Culture

I’m convinced by Lyman’s argument that birth subsidies work. This may be hard to see because countries don’t spend all that much on pro-natal policies compared to things like taking care of the old and national defense. A policy that gets fertility up by 0.2 per woman results in many more births, but you need to do a lot of social science in order to be able to establish a causal connection. So if Hungary’s TFR is 1.5, it’s hard to know if that means Orban’s policies failed, or that it would otherwise be 1.3 if he did nothing. The point of social science is to try to answer these questions. And I think that in general, the common sense notion that paying people to have kids actually does influence their decision making is sensible and backed up by data.

Just because something has an effect doesn’t necessarily mean it is cost justified. Lyman’s report advocating for expanding the child tax credit claims it would cost $200 to $350 billion extra over five years. That’s $40 to $70 billion per year. He estimates that this could increase the US birth rate by 3 to 10 percent. In 2024, there were 3.6 million babies born in the country. Three to ten percent of that is between 110,000 to 360,000 births a year. If these numbers are correct, you end up with a cost of something like $1 million-$3 million per child. This is a bargain from the perspective of most cost-of-life calculations that are cited to justify government policies. The numbers usually used are probably too high, but the $1 million-$3 million range seems like a good deal, and the fact that we’re talking about babies, who obviously have longer life expectancies than adults, makes the case even stronger. Moreover, there is reason to believe that every child increases the likelihood of other people having children through shifting norms, other cultural effects, and making society more accommodating to families, further adding to the case for subsidies, assuming these effects aren’t already fully captured by estimates of the effects of pro-natal policies.

Since we’re being honest, it is of course preferable for more new children to be concentrated among the responsible and wealthy. It makes sense to tie fertility support to the opportunity costs of working, which is associated with the likely contribution children of high earners will eventually make to society. I hesitate to fully embrace parental leave requirements, as when government is interfering in the economy I usually prefer direct cash payments instead of unreasonably burdening employers and messing with the market. But if parental leave, which is tied to income, is the only politically plausible way to reward people for having children in a way that is somewhat proportional to their sacrifice and contribution, then I may have to reluctantly support it. Allowing families with kids to pay less in income taxes, which Hungary has done, is also a good policy for the same reasons.

I’m generally a libertarian because I care about individual liberty and efficiency and care nothing for equality. With birth subsidies, you still have the liberty concern, but I think they can be justified on utilitarian and cost-effectiveness grounds. Moreover, if they shift the culture in a more pro-natalist direction, that’s even better. The preference of course is that subsidizing births should be done in conjunction with dismantling the other aspects of the welfare state. If expensive pro-natalist policies are just added onto existing programs, they might take us further down the path of fiscal irresponsibility. Overall, support for having kids is by far the least objectionable form of welfare spending, and should be encouraged. Often, the same policy can be portrayed as either “cutting taxes” or “increasing spending,” so if you’re worried about maintaining an adherence to dogmatic libertarianism, then just think of child subsidies as instances of the former.

Ultimately, we need a cultural change here. I find compelling Lyman’s argument that having kids never made economic sense and we have always had to find ways to culturally incentivize large families. I also agree with him that raising the status of parents means, by necessity, lowering the status of non-parents. Educated people virtue signal today by being non-racist or environmentally conscious. They should virtue signal instead by creating new life. We’re very far from that world, as having kids is seen as approximately neutral.

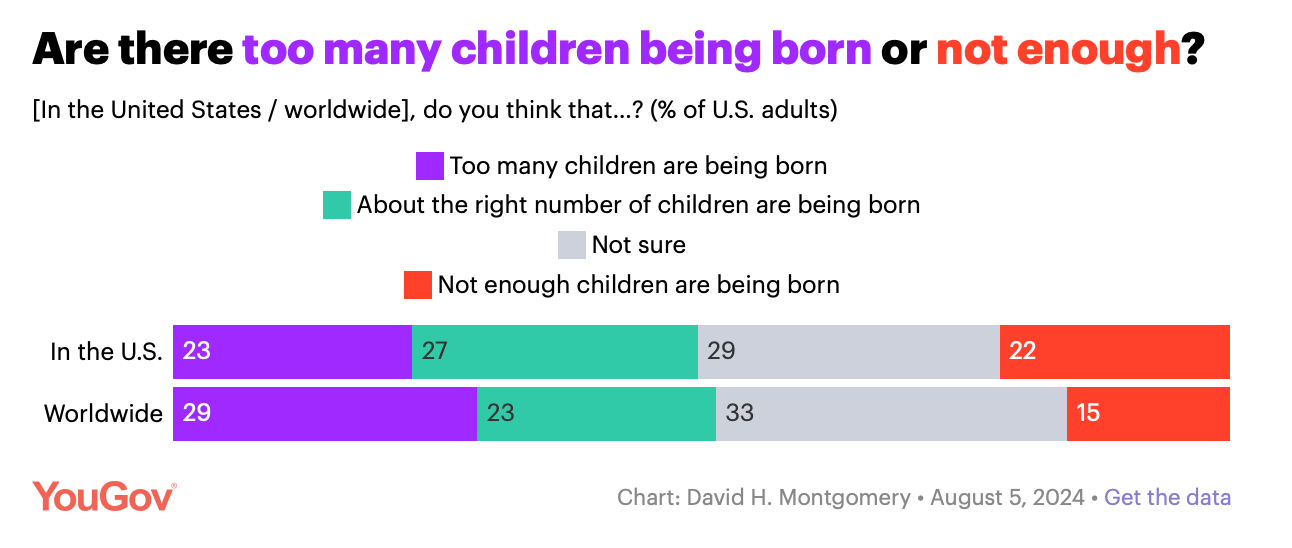

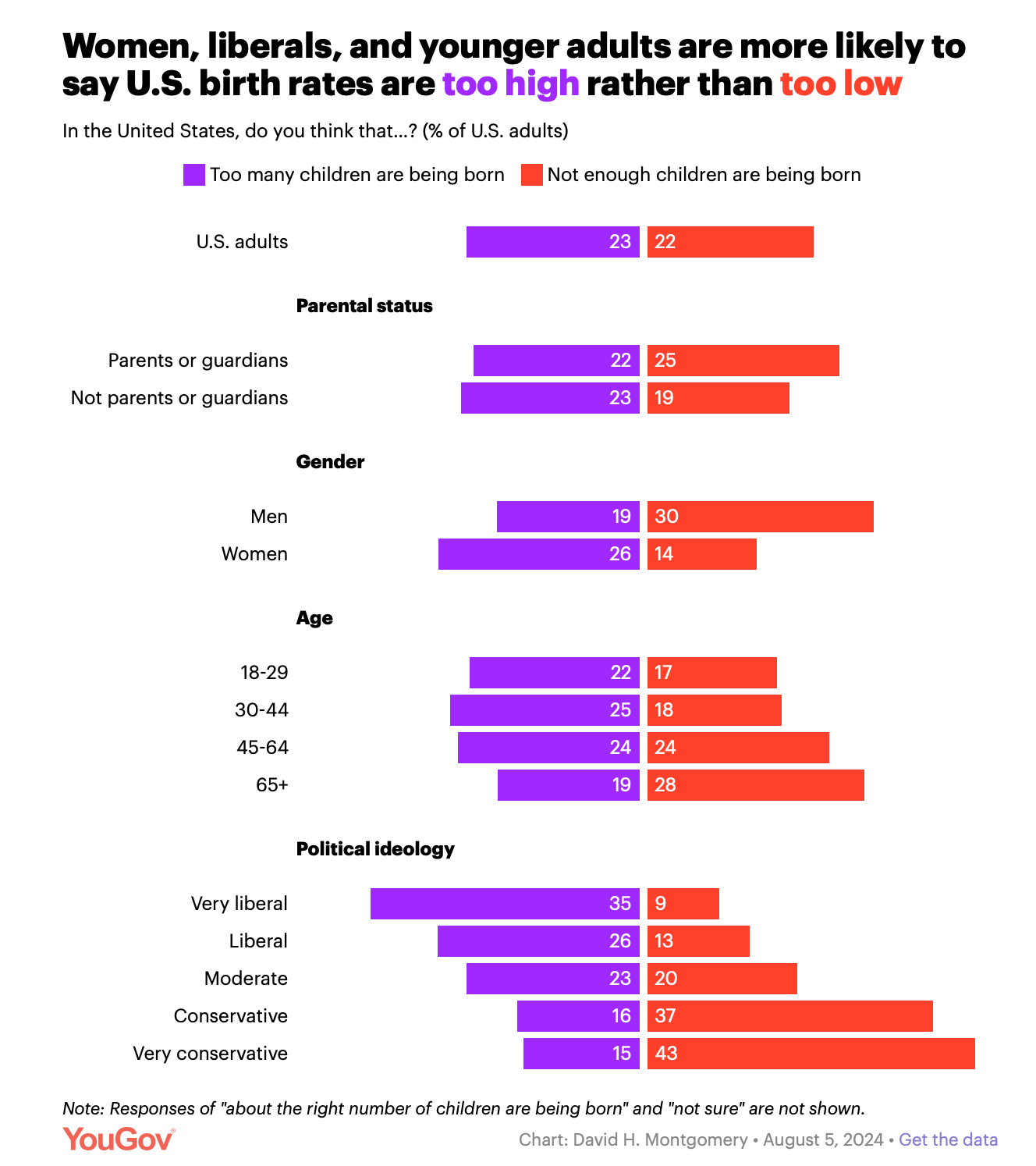

YouGov shows that ideology is an extremely strong predictor of whether you think there are too many or too few babies being born in the US. Americans who are very conservative are 28 percentage points more likely to say not enough children are being born in their county over saying there are too many, while among the very liberal it’s 26 points in the other direction.

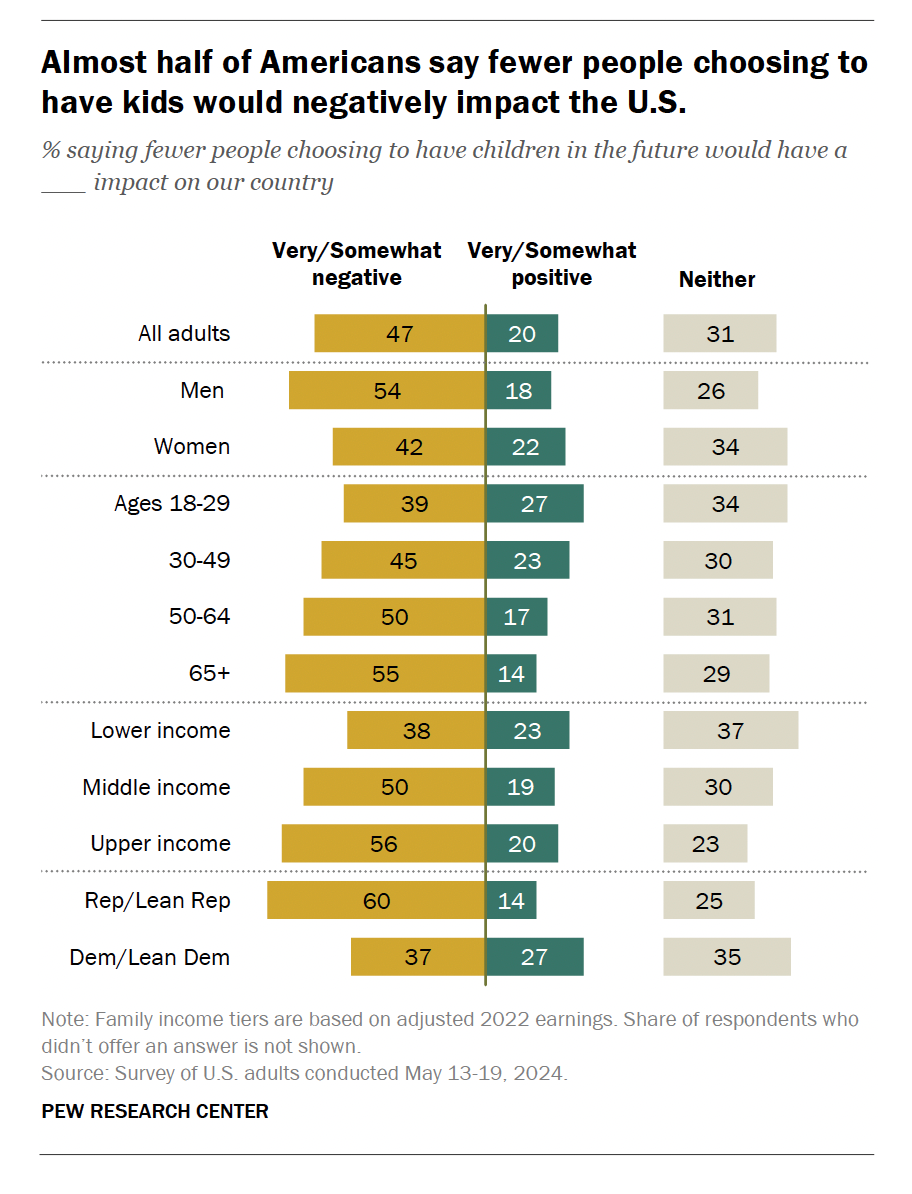

A different poll from just a few months later from Pew Research appears to be a bit more optimistic, showing that 47% of Americans believe fewer people having kids would negatively impact the US, compared to 20% who say it would have a positive impact.

We can probably reconcile these surveys by referencing the status quo bias. If you ask people whether there are too many or too few children, perhaps they just shrug their shoulders. But if you propose a deviation from the status quo, like a hypothetical of fewer births occurring, then they’re inclined to think that what you’re proposing is bad. I would actually be interested to see what people would say about the potential effects of more people choosing to have children, but Pew didn’t appear to ask that. For all we know, the public could be just as hostile to that possibility.

Interestingly, in 2025 Pew did the same poll, and found that the number of Americans who thought fewer people having children would be a bad thing had gone up, particularly among Democrats. I wonder if this is the downstream effect of normie liberalism seemingly beginning to worry more about the fertility question.

Regardless, I think the real lesson of public opinion here is that people are largely indifferent to having kids as a moral question. And indifference isn’t enough to overcome the disadvantages of creating and raising new babies, since you need positive steps to increase the status of parents. By having children, they lose out in terms of earning opportunities and energy they can otherwise put towards improving their status through other means. Society needs to find a way to compensate.

The status gained from parenthood needs to at least be as high as the opportunity cost of parenthood. For this, you need to actively say that having children is a moral obligation, it is good for one’s self and society, and it has positive social value. This by necessity lowers the status of those who are childless, and even those who stop at one or two. If this doesn’t happen, you’re not doing enough to overcome the headwinds that have led to sub-replacement fertility in nearly every developed nation, and even many poorer ones.

Status is not completely zero-sum. One benefit of living in a liberal country is the existence of multiple status hierarchies, so the total amount of status in one society can be higher than it is in others. Today, subcultures like those of the Amish and Mormons do raise the status of parents, but to solve the fertility problem at mass scale, we will need for childlessness to be much more negatively marked in the broader culture.

In my own life, I’ve sacrificed a lot to have children. I don’t get enough sleep. I live on the West Coast when I should be out East. I should travel a lot more, write about my experiences, and do more in-person interviews. But I had kids, and have lost some status as a result given our current value system. It should be adjusted to reward me for creating new life.

I don’t have a public relations plan for how to change mass attitudes, but I’ll do my part by saying it is good to have kids and you should do it, and I think less of you if you don’t. When friends tell me they’re having kids, I act happier for them than I do when they get a job promotion or accomplish some other less important goal. Once, a friendly Asian girl in law school told me that she was disgusted by the idea of something growing inside of her, and I expressed a socially appropriate level of disapproval. Every bit helps. There might always be a backlash to moralizing, but clearly not moralizing on this issue hasn’t led us anywhere good, and I work hard to gain status and make logical arguments so my pro-natalist preaching will have a positive effect.

Preferably, we get higher fertility while protecting abortion rights, and encouraging surrogacy, IVF, and ultimately genetic engineering. I already talked about not wanting to be political bedfellows with the fascists, but pro-natalism also puts me on the side of those who are socially conservative on these issues. I will say that I feel less uncomfortable with this crowd, as I’ve found that they’re more likely to be decent people than the ethnonationalists, who I think are mostly driven by sadism and hate. We can see this in the fact that many social conservatives reject Trump and MAGA, while practically every ethnonationalist is a Trump supporter and completely unbothered by his dishonesty, corruption, and lies. Religious fundamentalism and hostility to outsiders seem to be part of the same rightoid general factor, which means they correlate together. Still, the conservatives who are high on the religion sub-factor but limited on the racism one seem to be much better people overall than those who show the opposite pattern.1

The other reason to respect religiosity is that many faith communities have found the social technology to maintain decently high fertility under modern conditions. It’s possible that having a culture that is pro-natal enough for my taste isn’t compatible with having one that holds some of the other values that I care about. I’m willing to live with that though, as I think that the cause of pro-natalism is important enough for me to be willing to sacrifice on other things.

Since Anatoly Karlin came up with the concept of a rightoid general factor, I ran the idea of ethnonationalists being worse people than religious fundamentalists by him to see what he thought. This is what he wrote in response.

In today’s American context, I think that’s about correct.

But an important caveat.

This would not have been correct 10 or especially 20 years ago when American society was much less secular, and when Alt Right type people were more into IQ charts and Igbo research than nocturnal demonic attacks. Conversely, the LHC religious conservative types would have been Jerry Falwell/Pat Robertson followers and “Final Phase” conspiracists previously. The collapse of religiosity has collapsed their pool of adherents while average IQ and rationality remained at similar levels, hence the shift to secular ethnonationalist MAGA. (Personally, while I can easily talk to and even have fun with such MAGA people, esp. if booze is involved, I can’t imagine doing that with LHC fundies, and I suspect that is also true for you). Indeed, sociologically, it’s a transition from something quite distinctly American, to something quite redolent of Eastern Europe.

It’s also less true or not at all true in countries where the nationalist right hasn’t been eaten by the Rightoid International (a hypercompetitive American creation that now dominates a previously diverse ecosystem, much like with McDonald’s/KFC and the global ecosystem of cheap eateries). To be sure, many “national” nationalist subcultures were still overwhelmingly dumb even before this, but nonetheless, there were real islands of intellectual... if not excellence, then at least respectability (e.g. the Sputnik & Pogrom ecosystem in 2010s Russia that I’ve blogged about).

Strong piece, and the Julian Simon framing is exactly right. I'd add one diagnostic refinement: the stated vs. revealed preference gap you identify isn't just about tradeoffs—it's about identity strategy.

When Gen Z Harris voters rank "having children" 12th of 13 priorities (6% essential) while Gen Z Trump voters rank it 1st (34% essential), we're not seeing different calculations about the same goal. We're seeing fundamentally different conceptions of what constitutes a fulfilling life. The economic barriers are real but not binding—they're post-hoc rationalizations for choices already made at the identity level.

This is why Nordic subsidies fail despite eliminating economic barriers entirely, while Utah County achieves 2.1+ fertility without them. Sweden solved the wrong problem. Utah County built identity infrastructure—community networks, family-oriented culture, migration mechanisms that concentrate family-formation people—and got the outcome subsidies couldn't purchase.

Your point about needing status to exceed opportunity cost is the key insight most policy wonks miss. You can't subsidize your way to status. You have to build environments where family formation identity is normative rather than exceptional.

I explore this at length in my forthcoming book on why America's "problems" are actually structural advantages—federalism lets Utah County exist while progressive metros run different experiments, mobility lets families sort toward what works, and free speech lets us have exactly this conversation. The repair mechanism is already operating.

—Chris Wasden

What was not addressed here is the question of opportunity cost. If we want more Americans, and we are willing to spend billions (or even trillions) to increase the population, the best way to do this would be to pay more immigrants to come to our country. Now, if we get all 8 billion people to come to America and empty out the rest of the world, and the birth rate is still a problem, then we can start thinking about welfare for natalism. But the gains from immigration are so massive compared to natalism that it doesn't seem like a good utilitarian calculation, if we had to choose one over the other. As you mentioned, my problem with empowering natalists is that they do generally seem to be nativists and nationalists.