Human Capital, Not "Industrial Policy," Explains East Asian Success

The real question is why Koreans are so poor

The Cold War ended in spectacular fashion. Two great ideological powers went head-to-head with different systems of government, and one of them achieved such a clear victory that the other shrugged and said “yeah, we suck, I guess you guys were right.” There’s been nothing like this I can think of in human history.

Communism failed, yet people still don’t want to accept that markets are superior to central planning, so some scaled back their claims and began arguing that what nations needed was something called “industrial policy.” The government doesn’t have to control resources directly, but rather it must take an active role in deciding what it is worth investing in and the kinds of products it wants to manufacture. The state must control capital, as setting up a well-functioning legal system, solving narrow coordination problems, and otherwise leaving things to the market is insufficient.

I previously told you not to talk about race and IQ. Here, I’m going to talk about nations and human capital. With that bit of cover, plus some data analysis, maybe we can scare away the ethnonationalists. One should only make arguments like this if they’re necessary, and here it is because supposed East Asian success is basically the last argument for central planning. Ironically, ethnonationalists seem to love the idea of industrial policy, and are impressed with China, even though it is a very poor country relative to national IQ, a concept they supposedly believe in. This is partly because they’re authoritarians. But other types of people also think that East Asian success is something that needs to be explained by policy, and it is important to refute this idea.

The East Asian “Miracle”

The success of East Asia is basically the number one story in global economics since 1945. After the end of World War II and most of the colonized world achieved independence, there was hope that new nations would catch up to the West. That generally did not happen, except for Israel, a few oil-rich Gulf countries, and a handful of states in East Asia, namely Singapore, Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea, with China appearing to be on a similar path. For the most part, the countries that started out rich stayed rich, and the countries that started out poor have stayed poor. This has had economists and intellectuals more generally looking around for answers as to why this is.

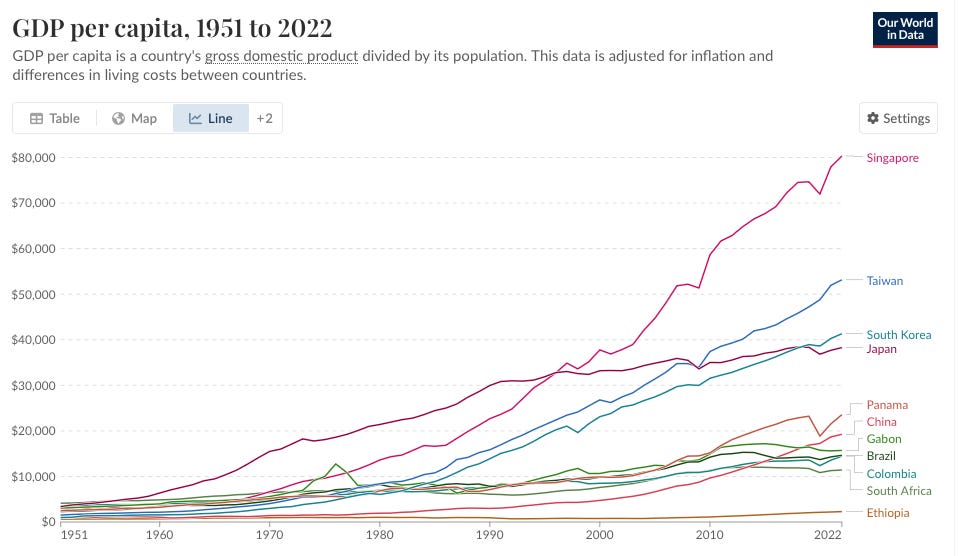

Here’s a chart showing how much East Asia has surpassed some other nations that started out at similarly low levels of development in the era after the Second World War.

As of 1950, Taiwan, South Korea, and China were all poorer than Brazil, Panama, and Gabon. Japan and Singapore were a little better off, but still behind Colombia and South Africa. Since that time, East Asia has blown past other non-Western countries. China got a late start here, only beginning to see real growth in the 1980s, but the takeoff has been rapid, and it looks to be headed toward the living standards of its neighbors, though this is complicated by the fact that its birthrate has collapsed while it is still a middle-income country.

The Gulf Arab countries have oil, but what did East Asia have? Why was this the only region of the world that started out at the very bottom rung of development and then took off, without natural resources being the explanation?

Joe Studwell’s How Asia Works (2013) is probably the most famous book arguing that industrial policy is the answer. He writes,

To the modern economic ear, accustomed to ideas of free markets that are supposed to be ‘win–win’ for all participants, policies to protect local industry and create a forced march for exports may sound more like a list of crimes. In rich countries, we are raised to believe that all wealth is the product of competition. The shocking truth, however, is that every economically successful society has been guilty, in its formative stages, of protectionism. Outside of the anomalous offshore port financial havens such as Hong Kong and Singapore, there are no economies in the world that have developed to the first rank through policies of free trade.

The problem here is that, as Scott Sumner has pointed out, basically everyone does some form of industrial policy. This is not necessarily because industrial policy is a good idea, but because politics leans towards letting concentrated interests get their way. Businessmen lobby the government for special privileges, leaders like having power, so whatever kind of cronyism evolves in a nation gets called “industrial policy.” When countries get rich, we say it’s thanks to industrial policy. When they fail, we say that they didn’t do it correctly or maybe the leaders were greedy.

Studwell, of course, doesn’t say that any old industrial policy will do. He tells a story in which there are three steps you must take to get wealthy:

Redistribute land to maximize output from agriculture

Direct investments and entrepreneurs towards manufacturing

Interfere in the financial sector to make sure to support small-scale agriculture and manufacturing development

The market won’t take step three on its own, because businessmen and consumers have time horizons that are too short. Some countries pursue “import substitution industrialization,” which involves protecting manufacturers in order to have them sell to the domestic market. East Asia, in contrast, sought export-oriented growth, where firms were encouraged and incentivized to sell to the rest of the world, which made them subject to market forces. Nations of the region pursued his preferred policies and then grew, and other countries can learn a lesson from this.

There is nothing in Studwell’s book, other than short time horizons, that explains why governments (and only East Asian governments!) are better able than markets to direct the efficient use of capital. Investors buy long-term bonds all the time, and entrepreneurs make bets that won’t pay off for decades. What makes it so much more difficult for the market to direct resources toward the most efficient long-term uses of capital in developing countries, and why can we expect better from government? Studwell believes in economic incentives, but seemingly only for farmers and individual factories, not for private investors. He tells us that the issue is that investors and consumers have too short time horizons, but then provides examples of land reform increasing productivity almost immediately.

This is strange, as he spends a lot of time arguing that small-scale farming is more efficient than large-scale farming, hence land reform makes sense as a way to increase productivity. But if that’s true, why can’t the market see that? Large landlords would have an incentive to split their land up in a way that would maximize efficiency. If elites in countries like Japan and Korea are as a class too set in their ways to do this, then under free market competition investors might buy the farms from them and make them more productive, or the small minority of owners who figure out how to better run their businesses will outproduce the rest. There’s no theoretical reason why markets should not get to the more economically efficient outcome in the absence of government restrictions on trade or commerce. The idea that you need the state to figure these things out is asserted but never explained.

East Asians Are Economic Underperformers

Studwell’s arguments lack strong theoretical foundations, and mostly rely on empirics instead. The question therefore becomes whether we actually need to invoke government policies to explain East Asian success. Surely, policy matters somewhat, which is why China did not achieve rapid growth under Mao and why North Korea continues to live in abject poverty. But among countries that have adopted somewhat normal policies, one may wonder whether choices that governments made were all that important for cross-national comparisons.

There are two ways to look at East Asian economies. From the perspective of poor countries in the mid-twentieth century, they’ve massively overperformed. But from a human capital perspective, they are mostly underperformers.

Every three years, the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) undertakes tests measuring the skill levels of 15-year-olds in countries across the world in Math, Science, and Reading. Below shows performance plotted against GDP per capita, adjusted for PPP. I take the average of the scores for Math, Reading and Science for the x-axis.

I use PISA rather than IQ scores for the primary analysis mainly because the latter makes people uncomfortable, and PISA is a gold-standard educational assessment carried out across the world on representative samples. There have also been tables of IQ scores put together through the gathering of various sources, including PISA, and Leonardo Parra and Emil Kirkegaard just released a new one. Basically, it doesn’t matter what source you use to make cross-national comparisons, they all show the same things. PISA is the highest-quality data and also the most difficult to argue with, so I’m going with that instead of stepping into the national IQ morass.

The East Asian countries and territories are highlighted in the chart above. Chinese and South Korean industrial policy are often held up as major success stories. But both nations are underperformers given the cognitive abilities of their populations. Taiwan and Hong Kong are about where you would expect them to be. The urban centers of Singapore and Macau blow other East Asians out of the water.

Note that the PISA score for China is an estimate. In 2022, data from China wasn’t collected due to Covid restrictions. So I started from the average score in 2018, when it had the best performance in the world. I had to make an adjustment, since for China the students were drawn from the urban centers of Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang (B-S-J-Z). I assumed that Chinese students in those locations were one standard deviation over the national norm, with the standard deviation calculated from the sample of cross country scores. I think this is beyond reasonable. B-S-J-Z has a combined population of nearly 200 million! If they were their own country, they would be the fourth largest nation participating in PISA. A one standard deviation adjustment is probably way too much, corresponding roughly to the gap in test scores between the highest and lowest performing American states. But even with that adjustment, China still comes out as a very smart country that has not done that well economically.

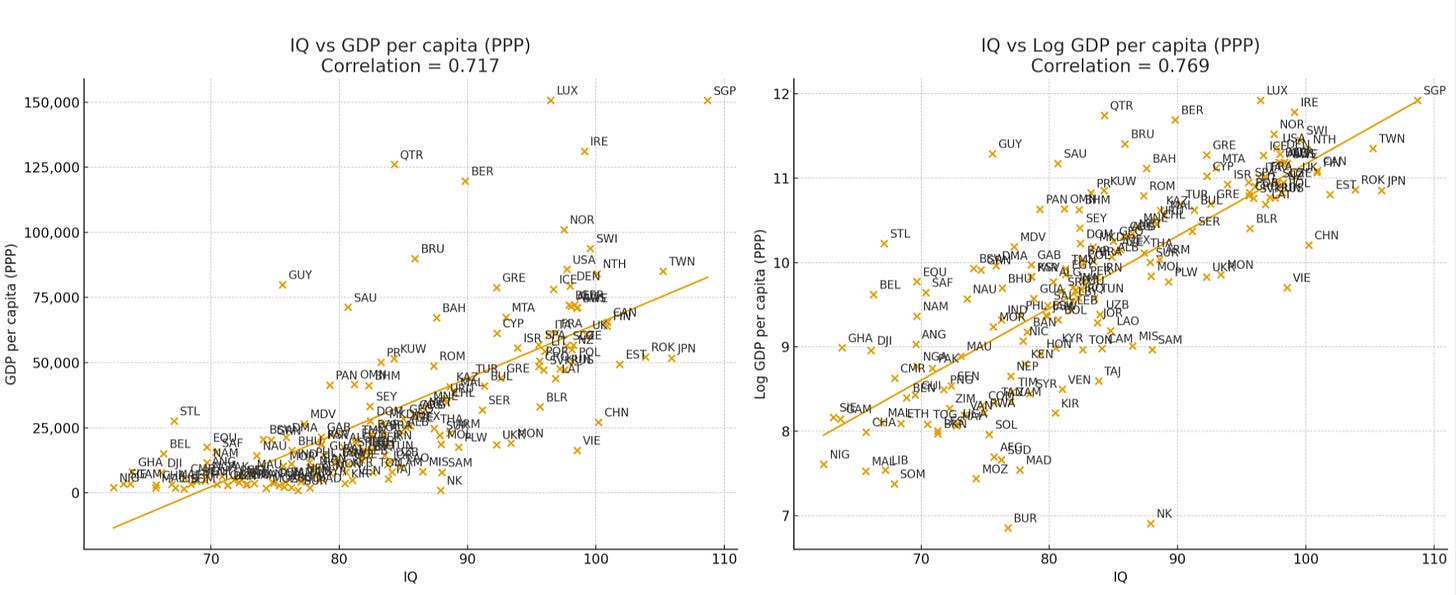

Just for fun, let’s use the Parra and Kirkegaard IQ scores for the same analysis, and see how they correlate with wealth. The CIA World Factbook gives North Korea a real GDP of $600 in 2023. I’ll take into account uncertainty, be generous and prop them up to $1,000. I also relied on the CIA World Factbook for the economic data for Venezuela. In the graphic below, I made a chart that uses unadjusted real GDP per capita and another that has that number logged, since among the poor countries near the bottom they all clump together.

Anyway, it’s basically the same story. Whether Singapore does better than expected or is exactly on the line depends on whether we take the log of the GDP numbers or not. Now, with an IQ estimate for North Korea, you get them as the world’s worst performing outlier. I wouldn’t take the North Korean IQ score too seriously, as it is estimated from tests of refugees. Are they positively or negatively selected? Who knows. But they apparently score about 16 points lower than South Koreans, which means even if positively selected to some extent, North Korea is still surely smarter than any other country at a similar level of development.

If you think Emil Kirkegaard is too racist to trust, here’s a paper looking at cross-national cognitive ability by three mainstream scholars. The results are the same no matter how you gather the data. East Asians are the best performers, then Europeans, then most of the rest of the world, then sub-Saharan Africa. You can come up with whatever reason you want for this, but the pattern is undeniable and reveals itself no matter what measures you use or how you gather the data. There’s an attempt to cancel Richard Lynn now for being sloppy in estimating IQ scores in many developing countries, but regardless, his work has in a broad sense replicated about as well as anything we have in the social sciences.

One might try to argue that industrial policy somehow makes countries smarter. It is true that the arrow of causation runs in both directions. Smarter countries get wealthier, but we’ve seen many instances where nations getting wealthier has improved cognitive performance. That’s why North Korea and South Korea are perhaps 10-20 IQ points apart. But even North Korea isn’t that low by global standards, and China isn’t that wealthy despite its high cognitive performance. It’s about on par in its living standards with Serbia and Mexico – nations not particularly known for their accomplishments in science and tech. East Asians are always much smarter than their level of development would indicate.

This appears to be true even if we go back further in time. In IQ and the Wealth of Nations, Richard Lynn and Tatu Vanhanen cite two studies of Chinese IQ from the 1980s. The first (1986), finds a score of 100 for 5-to-16 year olds and 92.5 for adults, for an average of 97. The second, from 1984, shows an IQ of 112.4 among 16-year-olds in Shanghai. Western scores are normed at 100. If we average these out, we get evidence that already in the 1980s, the Chinese were just as smart as Westerners, if not smarter.

This is remarkable given how much poverty it was experiencing. The World Bank has China at less than $300 per head throughout almost the entirety of the decade. Countries that are this poor in Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East have never performed nearly as well on standardized tests. Even if China’s IQ was 91 at the time, it was well above every other nation in the world at a similar level of development, except maybe North Korea. The World Bank gives China an adult literacy rate of 66% in 1982, below many sub-Saharan African nations today. And yet they were still doing well on IQ tests.

Lynn and Vanhanen also cite a study giving Korean children in 1986 an IQ of 105. Korea was still a middle income country at that time, with a GDP per capita (PPP) of just over $8,000 in 1990. That’s poorer than Jamaica and Morocco are today. Both those countries participate in PISA, and as you can see above they don’t do all that well.

One more fun factoid here: North Korea has about as many Math Olympiad winners as India, despite having a 50 times smaller population and much lower living standards. If Parra and Kirkegaard are in the ballpark of being correct by giving North Korea an IQ score of 88, this is valuable information, because it gives us a theoretical minimum of how low East Asian IQ can go if you reduce them all to the lowest form of degradation faced by any modern people. Cognitive ability is much lower there than it otherwise would be under any other form of government, but still higher than much of the world. Even if the North Korean IQ were 80 – and this would be hard to imagine given their accomplishments in the Math Olympiads and developing military technology – the country would still be a massive overperformer in intelligence given how poor it is.

You might be asking yourself why East Asians are so smart. My experience is that if you hint that there might be something genetic going on here, even otherwise measured and intelligent people crawl into the fetal position, and start screeching and ripping out their hair. Since I don’t want to bring psychic trauma to anyone, we will call the reason for East Asian success “culture,” even though no one can explain how this East Asian culture magically survives the most extreme social upheavals imaginable, including Mao’s Cultural Revolution and three-quarters of a century under perhaps the most radical long-lasting personality cult the world has ever seen in North Korea. Do the cultures of present day North Korea and Japan seem similar to you? If you say yes, then I don’t really know what culture means.

Set aside also the fact that somehow the Confucian stress on forming families and leaving behind descendants appears not to in any way affect modern behavior. But Confucius from beyond the grave somehow still makes East Asians good at math. Whatever. We don’t need to bother ourselves with such paradoxes, and can even accept a theory of Global Kendism. It is enough to say that high East Asian cognitive ability is real and it precedes that region of the world becoming wealthy.

Simpler and More Complex Theories

The human capital theory is simple and direct. East Asians have high cognitive ability and make better inventors, workers, and entrepreneurs. As long as they aren’t subject to something as extreme as the rule of Mao or the Kim family, they will eventually achieve first-world standards of living. Policy matters in the same way it does for other countries, where free market reforms are good and central planning is bad.

The industrial policy story, in contrast, depends on a large number of unlikely assumptions. As Scott Alexander writes in his review of Studwell’s book,

He doesn’t have as clear an argument against geographic, biological, and cultural factors. Minus a sea or two, Japan, Taiwan, Korea, and China are basically contiguous. It seems weird that all the countries with good policies would be right next to each other. Also, is it just a coincidence that Chinese / East Asian people in Malaysia and Singapore (and now the US) are known for being especially smart, rich, and good with money? Just a coincidence that these areas have hosted some of history’s greatest and richest civilizations? Don’t these push more in favor of the geographical/biological/cultural theories?

Scott is compelling here, but he really undersells the degree to which Studwell relies on spooky coincidences. Japan’s successful land reform occurred in the late nineteenth century. Those of South Korea, China, and Taiwan occurred in the second half of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. East Asian success has been consistent across massively different systems and various historical eras.

Imagine that you had God-like power over history and were trying to design an experiment to see whether it is policy or human capital that matters more. You would take East Asians, and maybe assign them to different treatment conditions:

An ex-British colony that became independent in 1965 (Singapore)

An ex-British colony that was given to China in 1997 (Hong Kong)

A former Portuguese colony, now a special administrative region of China (Macau)

Over four hundred years of unified and independent government (Japan)

A former colony of the last country, aligned with the US (South Korea)

Give the last country a neighbor and make it the most closed society and extreme personality cult in the world (North Korea)

The winning side in the Chinese Civil War with a communist government (China)

The losing side in the Chinese Civil War with a capitalist government (Taiwan)

History was almost perfectly designed to test the theory that “East Asians will succeed in pretty much any circumstances short of being ruled by Mao or the Kim family.” Imagine looking at this history, all the diverse paths these nations took, and coming to the conclusion that they all just happened to adopt the right policies. How do you always get the same policies in East Asia regardless of what else is happening in the world? Their historical circumstances are massively different, and they all eventually led to fast development. I really don’t know what more a person would need to discount the idea that specific policies are what made this region of the world special.

Studwell doesn’t make any attempt to show that countries outside of East Asia didn’t try many of the same policies. For example, between 1980 and 1997, Zimbabwe redistributed 3.5 million hectares of farmland by finding willing buyers and sellers. The pace picked up in 2000, with another 10.8 million hectares then being redistributed through more coercive measures. Throughout the 1980s, Zimbabwe also pursued aggressive support for manufacturing and had strong capital controls. The country is nonetheless world famous as a basket case.

Ethiopia beginning around 2000 consciously attempted to follow the East Asian path. The results have generally been disappointing. As the researcher Mebratu Kelecha writes:

Accordingly, industrialisation was placed at the centre of Ethiopia’s development strategies, as evidenced by the ambitious manufacturing sector growth targets in the second Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP-II) of 2015–2020, which had the highest growth rates of any sector of the economy.2 These ambitious growth targets led to the assumption that Ethiopia is undergoing rapid industrialisation. The industrial policy, according to Hauge and Irfan (2016), included measures such as industrial skills and infrastructure development, expanding government lending to priority sectors, measures to promote exports and import substitution, and attract foreign capital and investment in industrial park development.

However, despite Ethiopia’s consolidated industrial development strategy, policy outcomes were sluggish across key sectors. Pérez (2021, 115) collaborate this assertion, arguing that Ethiopia remains less industrialised than the average in sub-Saharan Africa, with a manufacturing value added at 5.5 per cent of GDP compared to 11.3 per cent for the region in 2019. More radically, critics have argued that industrialisation does not exist in Ethiopia, dismissively claiming that the Ethiopian government run a successful public relations campaign selling ‘a story that doesn’t really exist’ (Johnson 1999).

Ethiopian policy included heavy state planning, public investment in infrastructure, targeted support for manufacturing, and close state-business coordination. The government controlled the financial sector to channel cheap credit toward priority industries, protected “infant” sectors, and aggressively courted foreign manufacturers — especially in textiles, apparel, and leather — through industrial parks modeled on Chinese special economic zones. Like the East Asian cases, Ethiopia pursued export growth rather than import substitution, sought to build a disciplined bureaucracy, and emphasized agricultural productivity as a foundation for industrialization.

Ethiopia has not experienced the takeoff success of East Asian countries. If you asked Studwell what happened, he would probably say that Korea and Japan did industrial policy the right way while African nations did it the wrong way. You can always make up a new story and tack on additional complexity to your theory. But given that the human capital argument is simpler and has no contradictory evidence that I can see, we should probably go with that one.

Korea Is Not a Model to Emulate

Studwell doesn’t approve of the policies of all East Asian countries equally. His favorite seems to be Korea, and his least favorite among those that have become developed nations is Taiwan. A lot in his argument depends on his claim that Korea has done better, with the book noting that it had a $2,000 advantage in GDP per capita at the time of publication.

According to Studwell, the problem with Taiwan is that, although it implemented capital restrictions, it “never used financial system control to implement a manufacturing policy built around big companies. Lending was thinly spread and short term.” Recall that this is a theory about how countries get wealthy in the first place, so TSMC, which was founded relatively late in 1987, doesn’t help with that. Moreover, that company has been a joint venture between the Taiwanese government and the private sector, which Studwell doesn’t approve of. He thinks the Korean model is the best, and the government generally did not own equity in Samsung, Hyundai, LG, or SK, whereas the Taiwanese state was a major founding shareholder in TSMC and has kept a significant stake for decades.

You may be confused here, as above I listed Taiwan as a country that has done economically about as well as one would expect from PISA or IQ scores, while Korea has done worse. This seeming contradiction is solved when we realize that Studwell doesn’t adjust for purchasing power parity. Korea was indeed wealthier than Taiwan in terms of nominal income in 2013, but this did not consider the costs of goods and services, which is something that can be directly linked to some of the South Korean capital controls that Studwell loves so much, along with the market domination of a few conglomerates that are able to mark up prices. When adjusting for purchasing power parity, the IMF lists Taiwan at $41,700 in 2013, compared to $36,800 for South Korea. So Studwell was wrong even when his book was published. By 2025, the advantage for Taiwan has grown to $85,100, compared to $65,100.

GDP adjusted for PPP captures actual living standards, which is what we should care about. The major Northeast Asian country that, according to Studwell, had perhaps the worst industrial policy, ended up doing the best economically. This is even granting that we should ignore the fact that Singapore and Hong Kong didn’t adopt industrial policy in the way Studwell wanted, with him brushing aside their successes as the result of them being financial hubs, therefore having little to say about the right path to pursue for most other nations.

South Korea-Taiwan is just one comparison. But again, Studwell’s entire argument rests on Northeast Asia doing better than the rest of the developed world due to policy choices. And across East Asia, he clearly likes South Korea the best. If the disparity in growth between East Asia and the rest of the world can better be explained by human capital, and countries with the less enlightened forms of industrial policy produced better results within East Asia, what is left of his theory?

Studwell’s comparisons between Northeast and Southeast Asia similarly leave much to be desired. After praising the land reform programs of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, he explains why seemingly similar policies in the Philippines didn’t work.

The Philippine government claims that the implementation of the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law has met most of its national targets. According to official data, by the end of 2006, 6.8 million hectares of a targeted 8.2 million hectares of farmland were subjected to land reform to the benefit of 4.1 million rural households. This sounds like north-east Asia. But it is not.

To begin with, the Filipino statistics count all kinds of new land titles that have been issued, not practical and physical changes in ownership. One-third of new titles are collective (and almost by definition incomplete), often covering hundreds or thousands of supposed beneficiaries. Much of the land which on paper has been redistributed has been leased back, or sold illegally, to the original owners or to others. Moreover, only one-third of the targeted 8.2 million hectares under land reform is private land – the rest is publicly owned forest where some farming takes place, or new farmer resettlement projects, or other non-private categories.

Later on, Studwell similarly writes “One of the most interesting country comparisons is between Korea and Malaysia, because under Mahathir Mohamad the latter made a unique political commitment within south-east Asia to industrialisation based on north-east Asian experience. Yet the outcome was far from what was hoped for.”

A lot of countries try land reform and industrial policy. When things don’t work out well, you can always go back and find the reason that they didn’t do it exactly right or it somehow doesn’t count. Maybe it is true that East Asian governments always understood how to choose the right policies and implement them in the correct way, while nobody else in the developing world can figure this out. If that is the case, however, why assume government programs are what is making the difference? Why not just posit that East Asians are more competent, and leave it at that? Why is “Northeast Asians always happen to choose the best policies under extremely different political systems” a theory that is preferable to “Northeast Asians are more productive under a market economy”? The latter is much more parsimonious.

Studwell’s refusal to consider any kind of human capital or culturally based explanations leads him into some entertaining directions. I got a particular kick out of this part.

In this respect, land policy is the acid test of the government of a poor country. It measures the extent to which leaders are in touch with the bulk of their population – farmers – and the extent to which they are willing to shake up society to produce positive developmental outcomes. In short, land policy tells you how much the leaders know and care about their populations. On both counts, north-east Asian leaders scored far better than south-east Asian ones, and this goes a long way to explaining why their countries are richer.

So Northeast Asian leaders just cared more about their people? What kind of explanation is that? Maybe it’s a cultural thing? But the whole book is about cultural explanations not having any power, and the need for us to focus exclusively on policy. So I guess Studwell’s theory is leaders who care → the right industrial policy → economic development. But I think once you’re adopting theories based on the idea that some governments are just staffed by better people, you’re conceding a lot to cultural theories, which is odd when your entire thesis is that they need to be rejected.

Studwell’s inclination towards hand-wavey explanations about why only Northeast Asians adopt the right policies reaches new heights of absurdity in the following passage.

Unfortunately, there were to be fundamental policy differences in Malaysia when compared with Japan, Korea and Taiwan. Compounded by an already lacklustre performance in unreformed agriculture, these differences were more than enough to derail Mahathir’s industrial ambitions. The new leader failed to grasp the need for export discipline, and on trips to north-east Asia his Korean and Japanese hosts did not explain the dirty secrets of protectionism to him. [emphasis added] This was hardly surprising when the self-interest of these states was now in selling turnkey industrial plants and construction services to countries like Malaysia.

If only they had told Mahathir the secret, which, unlike Northeast Asians, Malaysians somehow can’t figure out on their own!

At some points, Studwell’s deep admiration for Korean authoritarianism gets downright bizarre. Here he is writing glowingly about how Park Chung Hee terrorized the private sector.

It was twelve days after the 1961 coup, on 28 May, that Park and his colleagues began arresting businessmen. They did so under a Special Measure for the Control of Illicit Profiteering. There are conflicting accounts of how many businessmen were held, where and for how long. But it is clear that scores of the country’s most senior entrepreneurs were locked up. Seodaemun was one detention point. A few top figures, including Samsung’s founder, Lee Byung Chull, had the good fortune – or, more likely, the forewarning – to be in Japan. But the great majority of the country’s business elite was taken in. Park put the frighteners on the business community in a manner unprecedented in a capitalist developing country. He declared that the days of what he termed ‘liberation aristocrats’ – crony capitalists who bought favours from Syngman Rhee’s government and did nothing for their country in return – were over.

Imprisoned businessmen were required to sign agreements which stated: ‘I will donate all my property when the government requires it for national construction.’ In effect, this put the entrepreneurs on parole to do whatever Park required.

Why didn’t anyone else ever think of that before? Bring businessmen together, tell them they’ll take orders from the state. This is not the kind of thing that has a good historical record. Sure, it worked out relatively well in South Korea, but we have every reason to believe that basically anything other than communism would’ve worked in that country, because of the human capital endowment of the population. Even where Koreans did communism, they formed the most extreme, long-lasting, and competent – if your measure is establishing and maintaining control – form of communism the world has seen. And the fact that South Korea is much poorer than all of its neighbors with similar test scores except North Korea and China indicates that its system has been pathological, not something anyone else should emulate.

A final indication that human capital is the main advantage East Asia enjoys is, as Scott mentioned, the success of the Chinese diaspora in Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia. Studwell is clearly aware of this, as he lists affirmative action policies as one reason that Malaysia hasn’t done that well. Yet the fact that different ethnic groups in the same country can have widely disparate outcomes is itself strong evidence for human capital and cultural explanations of economic results.

Accounting for Low Rates of Social Pathology

There’s another perspective we can take that makes East Asian economic performance look even worse.

In the US, 97% of people who finish high school, get a full-time job, and get married before they have children avoid poverty. Imagine you could wave a magic wand and not only make the entire American population academically perform at the level of upper middle class white students, but also almost completely do away with illegitimacy, extreme drug abuse, and crime.

What do you think would happen to the American economy? Imagine how rich we would be if we cut all forms of anti-social behavior to fractions of what they are now. Urban crime in particular is a massive drain on growth, rendering many kinds of public transportation unusable, causing long commutes and basically making the housing stocks of major cities rot away.

Imagine that you’re much smarter than me, and I also party all the time and abuse drugs while you live a completely sober lifestyle. If I end up more economically successful than you are, you need to look inward and ask what you’re doing wrong. That is the situation of East Asia relative to the US and Europe.

Sometimes, people who want to defend East Asia will say things like “life is more than just GDP! Go walk around Tokyo and walk around Alabama and tell me Alabama is richer.” You’re missing the point here. It’s great that East Asians are not fat, stay quiet on the subway, and don’t commit crimes. But life in those countries would be even better if they could be as wealthy as Americans too. Higher GDP is not what causes American dysfunction. Rather, US economic success over Europe and East Asia is a mystery to be explained given the characteristics of the American population.

I wouldn’t completely blame policy for the fact that East Asia has largely failed economically when accounting for human capital and its lack of antisocial behavior. If I did, I would be no different from Studwell. It seems likely that there are East Asian personality traits that inhibit growth and are not likely to be malleable by government policy.

The Last Stand of Statism

Capitalism works. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, and more recently the US surpassing Europe, East Asia stands out as the one region of the world that supposedly shows that government planning can be beneficial as long as it does not go overboard.

I see no reason to grant this argument. Countries succeed or fail based on a combination of population traits and policy. When we hold cognitive ability as measured by PISA constant, we see that more free market jurisdictions do better than the alternative: the US outperforms Europe and East Asia, and among East Asians, Singapore and Macau are the two places that clearly overperform their potential given standardized test scores. In Europe too, the most free-market countries have grown the fastest in recent years.

One more thing to note here is that advocates of industrial policy are often even more irrational than indicated by the discussion above. Studwell was presenting his suggestions as a way for poor countries to get out of poverty and start developing. He wasn’t arguing for a set of prescriptions for first world countries to adopt, and explicitly says that the case for free capital markets becomes stronger the wealthier you get.

If you hear someone arguing for industrial policy today, they’ll often point to things South Korea and China did when they were dirt poor, ignoring that the US is already the wealthiest large economy in the world. You won’t find any serious person who thinks that Trumponomics is the correct policy approach for a country in our position. You’ll find some who think industrial policy is something third world nations should adopt, and this article has argued that this is wrong too.

This is reminiscent of the China Shock literature, where even the scholars who popularized the term still think that free trade has been good for the United States. The ideas of economic populists are so poorly supported that they must cherry-pick from academic literatures, but then also misuse the studies they point to in order to justify protectionist policies. Industrial policy does not explain East Asian growth. But even if it did, it would not provide much guidance for how the United States should behave today.

With the defeat of the Soviet Union and the complete discrediting of socialism, the rise of East Asia, particularly China, has emerged as the main talking point for those who distrust free markets. Since the topic makes people so emotional, we don’t need to dig deeply into where human capital differences come from. It’s enough to say that they’re clearly real and important. In addition to not denying this, we also shouldn’t pretend that they are completely immutable – countries do seem to perform better as they get wealthier. Nonetheless, East Asia was smart before it was rich, and China today remains a middle income country and blows nations at a similar level of development away on cognitive tests. The losing side of the Chinese civil war now has a real GDP that is roughly at the level of the United States. The fact that politicians and pundits in our country seem to be jealous of the success of China, which is about half as wealthy as our poorest American states, is a sign of how disconnected from reality we are.

Yes, yes, GDP is not everything. But it’s not nothing either. There is no reason to believe that the things people find preferable about Korea or Japan over the West are the result of those nations being poorer. Westerners have a lot of social pathologies. But making consumer goods in Chicago more expensive will not make the South Side of the city as walkable or charming as Tokyo. We should all focus on increasing GDP as the goal of economic policy. Things like crime and illegitimacy also matter, but call for different sets of analyses and policy tools to deal with.

If you want to blame capitalism for Americans being fatter and more criminally inclined than South Koreans, I might as well blame industrial policy for Korea’s rock-bottom birth rates and weird relations between the sexes. I wouldn’t do that, because I’m an honest guy who sticks to the evidence. And what it says is that the wealth of nations can be predicted in a pretty straightforward way based on only two factors: human capital, and the degree to which they embrace markets. Attributing American pathologies to greater wealth, lower taxes, or whatever is pure cope, and the next thing that skeptics of free markets fall back on once you continue to show that all their economic arguments are wrong. Pro-market types tend to be more rational thinkers and honest debaters, which puts them at a disadvantage in these discussions. So you’ll often hear lower crime and rates of obesity used to justify European or East Asian policies regarding trade or taxation, but rarely see someone in favor of more capitalism similarly say that the relatively high American birth rate has economic causes.

Why can’t everyone just accept that we should all be market maxing all of the time? There appears to be a clear psychological block here, as people simply refuse to fully appreciate how much capitalism clearly and consistently beats the alternatives. Major East Asian nations reaching a standard of living that is in most cases lower than the typical European country, and much below that of America, is an argument that industrial policy has failed, not that it has succeeded.

It seems like your fusion of liberal exceptionalism and elite human capital hierarchy creates dynamic where in many cases, you always have a story for how any outcome validates your worldview. For example, when China succeeds, you say it was their human capital, proving your perspective right. When China fails, it was their authoritarian anti-market system, proving your support of liberal economics & democracy correct. These explanations might be right. But when you shifted away from the right, you cited real world events like China’s covid policies as a major factor. You emphasised that you update your views when events call them into question. Can you think of a comparable case that could validate/disprove your views today? An outcome that your ideological opponents would find plausible/likely, but your perspective would definitively rule out.

This stuff is so out there. Literally every complex, capital-intensive physical industry in the history of the human race has been developed with extensive state support. Quick- name 1 time in the history of the civilization that a country has developed a shipbuilding sector without the state paying for & insuring the capital buildout? 6000 years of human history, pick any country, on any continent, ever. It's..... it's literally never happened. 100% of all shipbuilding industries in human history have been initially government financed.

Name 1 aviation sector any country has ever developed without state support. Anywhere. Literally doesn't exist. For an example of successful industrial policy, you could read up on the early history of Boeing- or, the postwar history of Airbus. Completely government financed from the jump https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Airbus

Name 1 time a country has developed a semiconductor industry without state financial backing. Again, has literally never happened ever- the amount of capital needed to get started is too tremendously large. "In 1986, Li Kwoh-ting, representing the Executive Yuan, invited Morris Chang to serve as the president of the Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) and offered him a blank check to build Taiwan's chip industry. At that time, the Taiwanese government wanted to develop its semiconductor industry, but its high investment and high risk nature made it difficult to find investors" https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TSMC#History

There are so, so many more examples (the whole defense industry! The whole space industry! Most electronics manufacturing! Most automotive manufacturing!) Believing that super capital-intensive, physical manufacturing industries exist without initial government financing is as delusional as anything the far left or far right believes. Just completely out of touch with objective reality