The Neoliberal Era Was Not Pro-Market Enough

Free market economists made government plateau, not shrink

In response to my article arguing that neoliberalism worked, some have pointed out that growth was actually slower in the neoliberal era, compared to the 1950s and 1960s. This view has had support among some prominent left-wing economists. Writing in 2010, Paul Krugman argued that:

Basically, US postwar economic history falls into two parts: an era of high taxes on the rich and extensive regulation, during which living standards experienced extraordinary growth; and an era of low taxes on the rich and deregulation, during which living standards for most Americans rose fitfully at best.

As previously argued, neoliberalism is now a term of abuse, in part because of the extent to which it dominated the intellectual life of a previous era. There is no going back to neoliberalism, since it was formulated to deal with the problems of a different time, including economic crises resulting from faulty management of the monetary system. Nonetheless, the Krugman quote shows that the debate over pro-market reforms continues, sometimes in the guise of discourse over neoliberalism. From that perspective, it is worth looking at the arguments of critics who say that the reforms of the 1970s and 1980s failed. We will see that they did not, and there is in fact every reason to believe that classical liberalism is still relevant today, providing a guide to policy going forward.

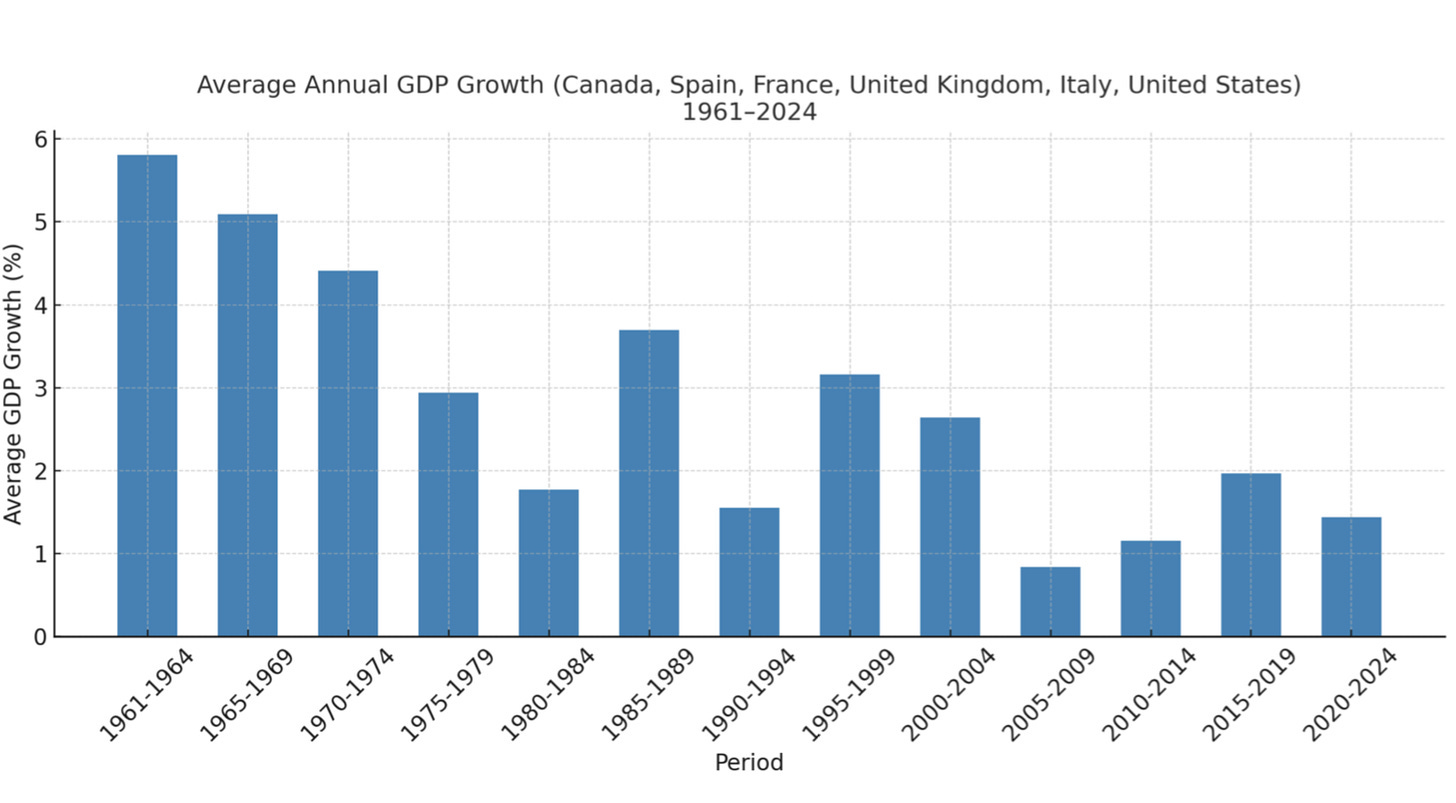

Krugman’s presentation of the data is correct. The chart below portrays average annual growth in four- or five-year intervals in six major economies: the US, UK, France, Canada, Spain and Italy. Data is from the World Bank.

Unfortunately for Krugman’s argument, in the fifteen years since he wrote the words above, the US has diverged more from Europe and large red states have seen a boom relative to blue states. While it is true that no major advanced country has returned to the growth rates of the 1950s and 1960s, the European Union in terms of tax and regulation policy is much closer to Krugman’s preferences than the US is. And yet things have not worked out nearly as well there.

In 2010, Krugman wrote “the European economy works; it grows; it’s as dynamic, all in all, as our own.” He noted that while the US grew at an average of 3% since 1980 compared to 2.2% in Europe, when you looked at per capita rates, the US lead was only 1.93% a year to 1.83%.

Yet the US has continued to pull ahead since then. GDP per capita growth averaged 1.7% in the US between 2010 and 2024, compared to 1.31% in Europe. That might not seem like a lot. But, if you imagine two countries that start out equal in wealth, with one growing at 1.7% a year while the other grows at 1.31%, both for 50 years, the fast growing country will be about 21% richer within two generations. Note that the US during this time period started out wealthier than Europe, and its higher growth rate is all the more impressive considering that catch up growth is generally easier than growth on the frontier of innovation. Initially small differences in living standards have compounded. For example, on a per capita basis and adjusting for the cost of living, the US was 15% wealthier than France in 1990; now the gap is 39%.

Moreover, using per capita numbers stacks the deck in favor of Europe. The US has over the decades welcomed large numbers of immigrants who on average earn less than other Americans. That means that the new arrivals are bringing the American per capita numbers down, and if you only compared natives to natives, the US advantage would be even larger. America has been adding more people and making everyone in society on average better off across multiple generations.

No one tries to compare the European economic model favorably to that of the US anymore. Today, Krugman admits that Europe has fallen behind, but attributes it to them working fewer hours, as productivity remains close. As with looking at GDP growth per capita rather than overall GDP growth, it is questionable whether we should want to make such adjustments in working hours. After all, Americans are free to work fewer hours if they so desire. If the European tax system and other regulations create fewer incentives to work so people take vacations instead – or, if as is often the case, they are forced to work less – it is unclear why that should be seen as a win for such a system. American innovation remains miles ahead of Europe in areas like medicine and tech, which means that our more productive economy has positive externalities for the rest of the world.

Nonetheless, even Krugman admits Americans are more productive per hour of work than Europeans are, and for this he blames fragmentation across European markets. If that is true, it indicates that more neoliberalism is exactly what Europe needs. What is remarkable here is that a committed left-leaning economist cannot find any data to indicate that stronger unions, higher taxes on the rich, and other economic ideas that are central to Krugman’s political identity make countries wealthier when comparing the US and Europe. The best he can say is that Europeans earn less money and take more vacations, which again Americans themselves are also allowed to do.

We therefore find strong evidence for classical liberal ideas working when looking at cross-national data. Nonetheless, slower growth beginning in the 1970s and continuing to today is a statistical fact, and one that must be considered when discussing the successes and failures of neoliberalism relative to what came before.

Government Did Not Shrink During Neoliberalism

The answer here is that there’s a common misperception that the neoliberal era shrank the size and scope of government. That is simply not the case. Despite some important changes in that direction, governments across the developed world in the neoliberal era were larger and doing more than they were in the mid-twentieth century. By the mid-1970s, that had caused a series of crises, with neoliberalism then being able to stabilize the macroeconomic situation through wiser monetary policy and stopping more dramatic expansions of government, setting the stage for steady and consistent growth. Countries, states, and jurisdictions that have had lower taxes and fewer regulations have seen superior performance since, indicating that we would have been even better off if the classical liberals of the time had achieved a greater victory. If neoliberalism did indeed fail, it is for this reason – it did not go far enough in creating freer markets.

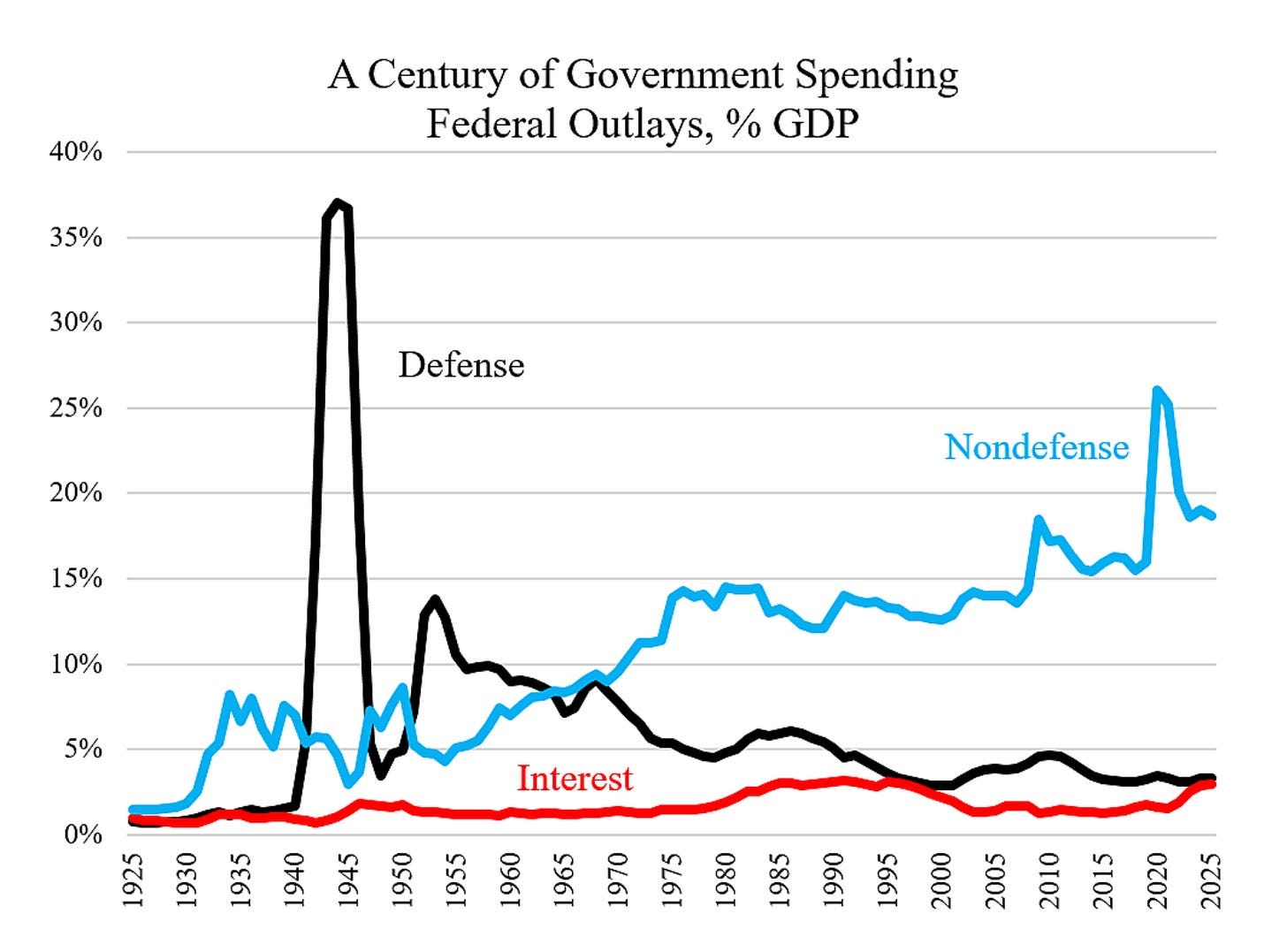

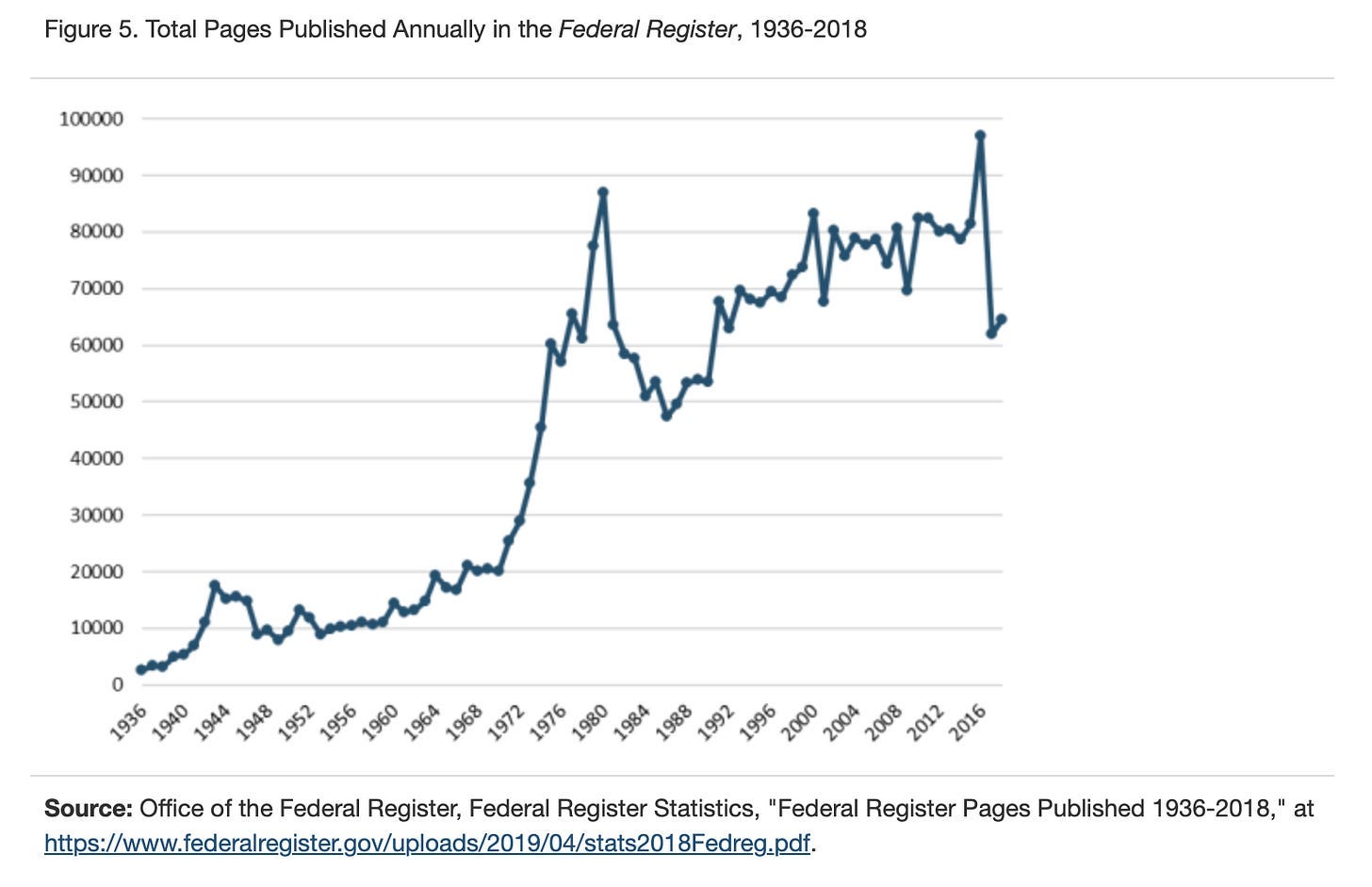

Consider the following two charts:

We can consider two ways to look at the intrusiveness of government: total spending, and the number of regulations. On both these measures, the US has had a much larger and more activist state in the neoliberal and post-neoliberal era compared to before. Non-defense federal government spending in the US rose from less than 10% of GDP in the 1950s and 1960s to around 20% today. Meanwhile, the federal government went from publishing on average about 20,000 pages of new regulations per year before the 1960s to over 87,000 in 1980. The number has since that time remained high relative to previous norms.

One has to be careful here, as more pages of regulations do not automatically translate into a more intrusive government. Especially around 1980, some of the new rules might have been moving us in a pro-market direction, as this was the immediate aftermath of President Carter signing the Airline Deregulation Act and other bills aimed at reducing the size and scope of the federal government. Yet the federal government publishing new regulations at a high rate every year over the course of multiple decades indicates that it is unlikely that a large portion of them have involved decreasing the power of Washington. At the state and local levels, land use regulations have also increased since the 1960s, putting a drag on economies and raising the costs of housing.

Unfortunately, I haven’t found data on the extensiveness of regulations over time in other countries. EU legislation has gone up over 700% since 1994, the year after the Maastricht Treaty went into effect, though we do not know if this came at the expense of national laws. EU laws are often “gold-plated” by national legislatures, which means that they serve as a kind of floor on regulations of the economy, circumventing the intent of national harmonization. Regardless, the pattern of big government persisting in the neoliberal era is clear, however, when we look at government spending as a percentage of the economy.

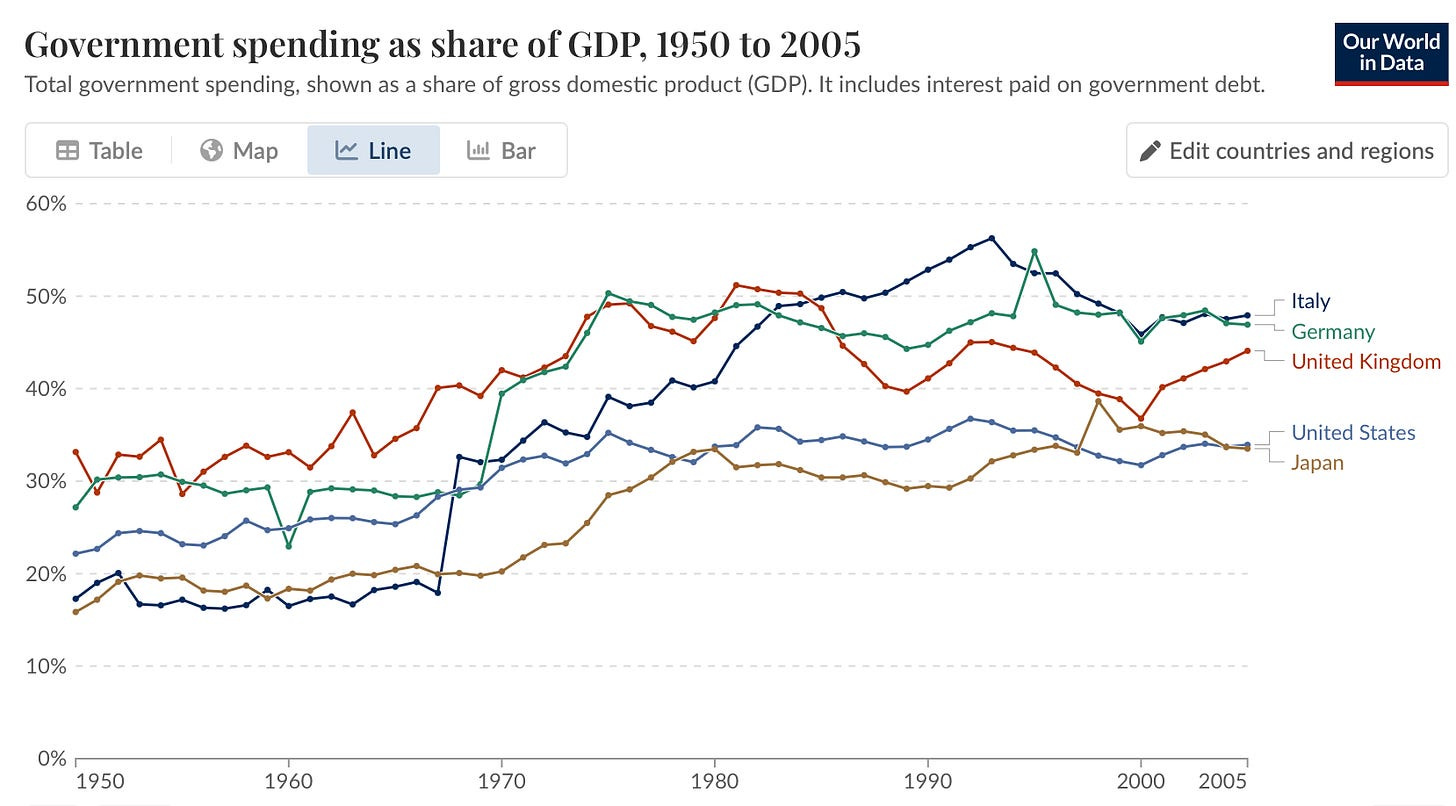

As with the US, we see large increases in Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom in the 1960s and 1970s, followed by a leveling off at higher rates than what had previously been the norm.

That brings up the question of what it means to even speak of a neoliberal era, since government in the aggregate does not seem to have shrunk or gotten less powerful, at least in developed countries. There are two main responses here.

First, the leveling off of the size of the public sector was itself a valuable accomplishment. There had been a long-term trend of government spending making up a higher and higher portion of GDP that went back to the nineteenth century. In Sweden, for example, the number was 7.2% in 1900, 12.2% in 1925, 18.3% in 1950, and 30.6% in 1975. It reached a high of 69% in 1993, but has been much lower since the Swedish financial crisis of the early 1990s, now hovering around 50%. Setting aside the Great Recession and Covid, the UK reached its all-time high in government spending in the early 1980s at just over half the economy – it has been closer to 40% in the decades since. The entire twentieth century was basically the story of governments getting larger and larger, until neoliberalism came along and stopped the growth, or in many cases slightly reversed it. That doesn’t mean, however, that anyone has gone back to pre-1970s norms.

Why weren’t leaders with genuinely pro-market convictions like Thatcher and Reagan able to make government significantly smaller? Here they ran into the limits of what democratic leaders can do. There is a status quo bias among the mass public, meaning that people generally support current welfare programs and government interventions while being more skeptical of any further expansions. Recall the rallying cry of “keep your government hands off my Medicare” during the Obamacare debate. Yesterday’s government programs are the ones we are used to and go to those like us, while new ones benefit the wrong kinds of people and are fiscally irresponsible.

The second accomplishment of neoliberalism is that it took on and defeated some of the most distortionary forces in Western economies. The US effective tariff rate was cut by about half between the mid-1960s and 2010, though that has now reversed under President Trump. Perhaps more importantly, price controls became unthinkable at the national level, as elites realized that such policies were particularly damaging after President Nixon’s efforts to freeze prices and wages across the economy led to shortages and stagflation. Transportation was also deregulated. Until the late 1970s, airline flights, routes and fares were subject to rigid controls by the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB). That changed with the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978, which unleashed market competition across each of these areas. The Motor Carrier Act of 1980 similarly reduced the Interstate Commerce Commission’s (ICC) control over routes, entry, and rates for trucking companies.

The decline in labor unions in the US and UK is another major accomplishment of neoliberalism. Unions are particularly destructive because they hinder technological innovation – the main basis of economic growth – and function as price floors across wide swaths of the economy. Thatcher during the 1980s passed a series of incremental laws that made strikes more difficult and restored managerial control in workplaces. In the US, right-to-work laws at the state level have prohibited compulsory union membership or dues as a condition of employment. Lower trade barriers also removed the bargaining power of unions, rendering them less able to make demands that would render businesses unprofitable. Trade union density has as a result of those reforms collapsed in both the US and UK. Additionally, market forces have played a role, as unionized industries and workplaces have grown slower or declined and been replaced with ones in which labor markets are able to operate freely. As with containing the growth of government, neoliberalism likely did a great service by simply maintaining the status quo and not trying to rescue organized labor as it brought down firms and industries in which it was powerful.

All of that is to say that while neoliberalism might not have done away with enough regulations or even stopped more from being added in the aggregate, it has limited the growth of government and largely focused on the right things. It has removed or mitigated some of the more destructive elements of economic statism, namely price controls, heavy handed regulations of transportation industries, and strong labor unions. The victory on tariffs is unfortunately being reversed by the Trump administration, but most other changes remain solidly entrenched, and Europe for its part at least has not turned away from the principle of free trade.

The lesson here is that systems inevitably build on what came before. When there was a consensus in favor of big government from the 1940s to the early 1970s, developed nations were starting out from very low levels of spending and intervention in the economy. They expanded the size and scope of government over the next few decades, until crises started to hit in the late 1970s and it was clear that there needed to be a new path forward. Ronald Reagan believed more in free markets than did LBJ. Nonetheless, Reagan left behind a much larger and more expansive federal government than Johnson did, despite their ideological differences. That just goes to show how leaders in democratic countries do not remake their societies from scratch. As a wise woman once said, you did not fall out of a coconut tree.

The Problem With Comparing Across Eras

Even independent of policies, it is likely a mistake to compare growth rates in different eras and attribute disparate outcomes to policy. The rapid rise in living standards of the first half of the twentieth century up to the 1960s may have been, as the economist Robert Gordon has argued, due to there being a great deal of low-hanging fruit in terms of new innovations and their applications, including the spread to nearly universal status of electricity, cooking fuel, running water, toilets, and, where the weather called for it, central heating and air conditioning. See what happened to life expectancy, which increased rapidly in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries but has improved at a slower pace since then in the developed world. Medical and public health interventions like vaccination, better sanitation, and indoor climate control can only happen once. Today, environmental laws and the latest medical breakthroughs continue to help make incremental gains in the first world, but it is easier to go from a life expectancy of 40 to 70 than it is to go from 70 to 100.

The story with technological innovation is not so simple, since here we are not dealing with hard limits set by biology, but rather factors that are much less tangible. The low hanging fruit argument holds that it gets more difficult to build on the accomplishments of the past as technology moves forwards. While in the days of Newton, a single individual could be credited with important innovations in calculus, physics, geometry, and optics, no such polymaths exist today as it is too much work to develop the relevant expertise in that many fields. At the same time, we are spending a lot more on science, and have greater tools with which to innovate – everything from laptops that can run statistical regressions to extensively funded corporate and university labs – which implies that it should be easier to make breakthrough discoveries. Whether the world having already captured much of the low hanging fruit in science and technology explains fewer consequential innovations in the last several decades is a topic debated by progress studies scholars. Of course, government policy itself must in various ways influence the rate of innovation, which adds further complications to the analysis. In other words, maybe we have fewer important new discoveries because we are overtaxed and over-regulated. Regardless, for our purposes we only need to say that there are all kinds of difficulties involved in comparing growth rates across eras.

The better approach is to compare similar countries, regions, and jurisdictions within the same era and see what kind of policies are associated with higher growth. That way, we at least hold the level of technological development constant. From that perspective, I would argue that the story that pro-market reforms are the best way to innovate and get wealthy is by far the one that is most in accord with the evidence. That fits with the general story in which the US has been more market friendly than Europe and seen faster growth since the 1980s, while in the US itself, states that are more market friendly have both drawn more people and gotten wealthier relative to the rest of the country, consistently over a four decade period. The divergence between the US and Europe in particular is difficult to square with a model in which more intrusive government, higher taxes on the rich, and stronger labor unions are better for growth.

Need more evidence? According to the Fraser Institute ranking of economic freedom, as of 2023 the only four jurisdictions in the world rated higher than the US are Hong Kong, Singapore, New Zealand, and Switzerland. Two of these nations, Singapore and Switzerland, have higher GDPs per capita than the US does, Hong Kong is about equal, and only New Zealand is significantly below. Among EU nations, Ireland is both the economically freest and the one with the highest level of growth in Western Europe over the last several decades. Although the topline numbers for Ireland are buoyed by the presence of multinational corporations, using other indicators such as GNI still shows it to be a remarkable success story.

Overall, the Fraser Institute finds that countries in the top 25% of economic freedom earn about six times more than those in the lowest quartile. There is no indication that we’ve hit diminishing returns in terms of neoliberal reforms, as the richest countries are the freest ones. We can only imagine how much success a country would have if it was so neoliberal that it made the US look like Europe, or if we had US states that made Texas look like California.

One might notice that, in addition to that of the Fraser Institute, which is co-published with the Cato Institute, there is an index of economic freedom put out by the Heritage Foundation. Each of these think tanks calls for smaller and less intrusive government. It is notable that there are no equivalent lists released by those who want higher levels of taxes and regulation, who must realize that there would be no way to massage the data in order to find results that are congenial. What they often do is compare the US to Europe on non-economic measures like life expectancy, which America does poorly on due to factors like obesity, murders, and car accidents. GDP does not capture everything, but in comparing economic systems, we should stick to economic data, rather than tying any negative indicator to a system we do not like. Nobody has come close to proving that Europeans kill each other less often and get into fewer car accidents because they are poorer.

Policy Implications

In the end, neoliberalism cannot be judged by whether it recreated the breakneck growth of the postwar decades. That is because pro-market thinkers themselves would argue that government has remained large and intrusive even after Thatcher and Reagan. Moreover, the state of technological development varies across eras in ways that are independent of government policy. What neoliberalism did, however, was place some limits on the trajectory of expanding statism that had characterized the developed world until the late 1970s. As a result, nations and jurisdictions that have adopted pro-market reforms have done better than those that took a different path.

The fact that the size of government across the developed world plateaued rather than shrank, while the rate of increase in new regulations in the US remained constant, reflects the reality of democratic politics: once programs are established, the public resists rolling them back. But for a few decades the ideological tide turned, and countries that did more to embrace the ideas of thinkers like Hayek and Friedman achieved faster growth, which is all that one can ask.

It can be argued that the lesson here is a pessimistic one. One might say you can’t stop the march of big government; you can at best freeze things in place or maintain a constant state of growth. The fate of classical liberals might in fact be to continually point out that things could be much better. Perhaps the greatest benefit lies in every generation focusing on where misguided policies are having the most distortionary effect and working for change. In 1970s America, the most damage was done by things like too easy credit, price controls, labor unions, and the regulation of transportation. Now, with those battles largely won, housing and the cost of building have emerged as among the top issues of our time, and there is increasingly bipartisan agreement in these areas on the need to remove regulations that are in the way.

At the same time, classical liberals should continue focusing on broader efforts to win hearts and minds. The fact that there is little to suggest that we have gotten to a point of diminishing returns in terms of market-based reforms indicates that there is still an inspiring future worth fighting for. That means continuing to make the case that the neoliberals of a previous era got a lot of things right, and if anything they did not go far enough in their reforms. That is reflected most remarkably in the way that the US has pulled away from Europe and East Asia and become what The Economist has called the economic envy of the world, led primarily by red states, in addition to the successes of the old communist bloc; the cities of Singapore and Hong Kong; and the smaller nations of Ireland, Switzerland, and the UAE. We have reason to believe that even in highly developed states, life can be much better than it currently is, as there is no indication that we’ve reached the limits of what markets can do. Understanding how pro-market ideas have already transformed the world can remind us how much progress remains possible if we continue to build on previous successes.

Excellent post. Money quote: "Unfortunately for Krugman’s argument, in the fifteen years since he wrote the words above, the US has diverged more from Europe and large red states have seen a boom relative to blue states. While it is true that no major advanced country has returned to the growth rates of the 1950s and 1960s, the European Union in terms of tax and regulation policy is much closer to Krugman’s preferences than the US is. And yet things have not worked out nearly as well there."

There's something realist-Hayekian to be written on following dynamic:

1) Classical liberalism is extraordinarily economically/geopolitically adaptive and therefore spreads.

2) Classical liberalism is extraordinarily unappealing to our evolved tribal-egalitarian hunter-gatherer instincts, therefore constantly being ditched.

So a kind of group selection is working against a psychological evolutionary mismatch. In principle, constitutional structures like federalism, balanced budget rules, and economic openness can favor 1) and slow 2).

Prior to the demographic transition, the game was easy enough: classical liberal societies (Anglo-America, lesser extent rest of Europe) were economically, technologically, and demographically dynamic, therefore geopolitically powerful, conquering vast stretches of the world. Nowadays economic power and demographic sucess are largely disconnected, so unclear what is sustainable. There is still group selection in favor of economically successful states in the form of brain gain and other immigration. In conjunction with higher productivity, this accounts for USA now making up an outright majority of G7 economy! But the USA might only be a generation behind Europe and Japan in terms of coming stagnation. Especially if populist corruption and incompetence becomes normalized across institutions. I have hope the rule of law, federalism, and the market can check negative trends, while reprogenetic technologies - pioneered by American technocapitalist frontier - can eventually solve the demographic challenge.

In addition to the intra-US differences (red vs. blue states) and US vs. Europe which you mentioned, intra-Europe variation in market-friendliness also clearly shows that more pro-market countries are wealthier. Switzerland, Ireland, the Netherlands all lead in pro-market policies and per capita income.

It is actually a huge problem for Europe that some of its biggest economies like France and Italy are the most statist, because it significantly drags down growth for the whole block (Germany has gotten worse with time as well). If all of the EU had the economic policies of smaller countries like Ireland or even the Netherlands it would be in much better shape.