The Discourse is Getting Both Smarter and Dumber

Understanding the future of human capital polarization

I spend a lot of time writing about how the discourse is getting dumber. Ten years ago, anti-vaxxers did not have any role in national politics. Now they’re running HHS. During Obama’s first term, the most prominent conspiracy theory on the right was that the president had been born in Kenya. That wasn’t true, but it’s a fundamentally different belief than the idea that Charlie Kirk was a time traveler who was monitored from the time he was a child, or even that each election Republicans lose was probably stolen. The leaders of half of the political spectrum now consider Nick Shirley, a 23-year-old who does not know common English words, a great journalist.

I’ve also discussed why this has happened. The internet, social media, and the removal of gatekeepers have all worked to democratize the public square. Dumb beliefs have always been prevalent, but political debates were previously curated by people like academics, TV producers at major channels, and newspaper and magazine editors. With that gone, the discourse surrounding politics increasingly resembles the broad spectrum of public opinions and attitudes. Crude prejudice, quack health beliefs, conspiracy theories, and primitive tribalism are having their day.

Four Heuristics That Have Made Smart People Smarter

That said, to stress only the story of us getting dumber is too pessimistic. I think that there has been a parallel trend, in which the highest levels of public discourse are getting better. Twenty years ago, there was no equivalent to Candace Owens, but there was also no Scott Alexander either. Fools can now find one another much more easily and reinforce each other’s views. But the same is true for smart people with good epistemological standards, who have faster and more copious access to information than anyone else in history, and can share ideas and discuss issues on platforms like Substack and X. They sometimes form group chats and more easily collaborate on projects. Below, I’ll go over just a few examples of how the highest-level discourse has gotten smarter over only the last two decades. Afterward, I will put forward some thoughts on where we go from here in terms of what the great human capital divergence means for politics.

Understanding polling

During the 2016 election, there was a debate between Nate Silver and other forecasters over the likelihood of a Trump victory. Silver was giving Trump about a 30% chance, while the Princeton Election Consortium and the Huffington Post put his odds at 1-2%. Both sides agreed about what the polls were saying and did not think they were biased in a predictable way. The difference was that Silver’s opponents operated on the assumption that there was a very small chance that the polls were all going to be biased in the same direction. Maybe the polls were wrong and Trump would do better than expected in, say, Florida, but what were the odds that the same candidate would overperform in Pennsylvania, Arizona, etc? To simplify this a lot, imagine that Trump needed to win each of four swing states to become president, and Hillary was a 70-30 favorite in each. In that case, we could calculate Trump’s probability of winning as 0.3⁴ = < 0.01, or less than 1%. This was the thinking of many election analysts.

Silver’s argument was that if, say, Trump overperformed in Florida, it’s a good indication that the polls are going to miss in a similar direction in other states. So yes, Trump may have had only say a 20% chance of winning Michigan going into election night, but if the Florida results come in early and he wildly surpasses expectations, you should revise your estimate of him winning Michigan upward. In technical terms, the Princeton Election Consortium and the Huffington Post were assuming the probabilities of a Trump victory given the polling in each state were statistically independent, while Silver considered the possibility of correlated errors.

Silver was of course correct. We don’t know this just because Trump won, although the fact that he did is enough to update one’s priors. I remember these debates at the time, and thinking that any reasonable statistician would’ve come to the same conclusion. Think about some of the reasons that polls might underestimate Trump’s support in a particular state. Maybe Trump voters don’t talk to pollsters, or pollsters underestimate the vote share of non-college whites, or there is some late breaking news that favors Trump over Hillary. Such factors are going to have nationwide implications, and are not going to be limited to one state.

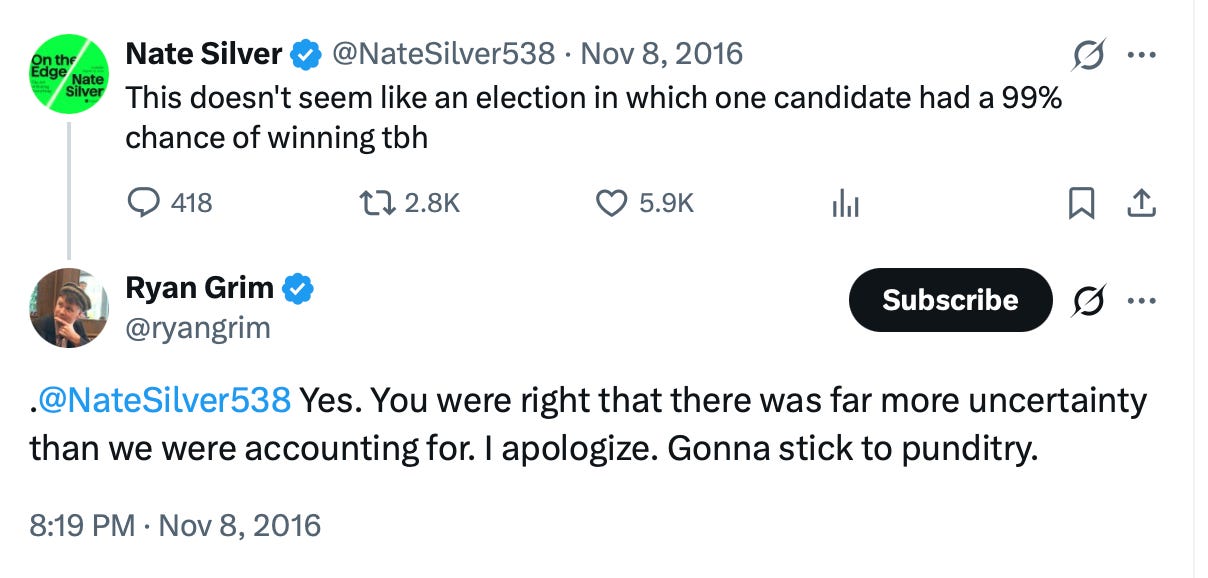

The night of the 2016 election, something remarkable happened. After having attacked Silver during the campaign, Ryan Grim of the Huffington Post admitted defeat. He tweeted to Silver, “Yes. You were right that there was far more uncertainty than we were accounting for. I apologize. Gonna stick to punditry.”

Ever since that moment, I’ve had a deep respect for Ryan Grim. He’s a leftist and I don’t agree with him on much, but here he did the honest and decent thing. More people should behave like this, and we should all praise them when they do.

I feel like Grim’s concession was the moment that educated people started to think about polls in a more rational way. In 2020, Biden had an even larger lead than Clinton did in 2016, and nobody serious was talking about him having anywhere close to a 99% chance of winning the election. That’s the kind of prediction you make when you understand some statistical concepts but completely ignore the real-world context. The Brexit vote also occurred in 2016, and though there was no correlated errors issue there, people were way too confident that the referendum would go down based on Remain having a slight lead in the polling. In addition to grasping the concept of correlated errors, I think we’ve also become more understanding of the fact that small misses are completely normal, and there isn’t much we can do beforehand to guess in which direction they occur.

It’s notable that Grim didn’t only say he was wrong, but also declared that he wasn’t going to do forecasting anymore. Part of the process of educated opinion getting smarter is people knowing whom to trust, and we now understand that we should listen to actual experts in statistics over pundits on these questions.

Putting less weight on individual studies

In 2010, a college professor could give a survey to a few dozen students, report on the results, and act as if he had unlocked a deep truth that told us something important about politics or society. Then came the replication crisis beginning in the early 2010s, through which we learned that many findings from the social sciences were less solid than once believed. Scholars started adopting better practices like preregistration, where you record your methods and predictions beforehand instead of just reporting your findings in a paper. To understand why this is important, imagine a scenario where a person suspects that rainy days make people more Republican. Our researcher conducts a study, and finds no correlation between the two variables of interest. He then finds, however, a statistical relationship between rainy days and supporting Democrats, but this only holds for women during the winter. The researcher ignores the original hypothesis and writes a paper that presents a novel theory about left-wing women and what influences their politics.

This is called “p-hacking.” Tests of statistical significance tell you what the odds are that a statistical relationship found came about by chance in a world where the real relationship was zero. A p-value of < .05, the conventional threshold for significance, indicates that if the statistical relationship were zero, there would be less than a 5% chance of getting the observed result. But if you test, say, twenty or thirty different hypotheses, you will probably find at least one statistically significant relationship by chance, even if the effect sizes you are measuring are zero across the board. And this is even before we get into model design and research protocols, along with other issues that emerge in studies that don’t involve randomized treatments. All of this is to say that you can’t put much stock in one or a handful of studies reporting a statistically significant effect, especially if the p-value isn’t much below 0.05 and there was no preregistration.

Last month, Matt Yglesias wrote about his time as a “studies say” guy. The easiest thing in the world for a pundit to do is look for abstracts of papers that seem to make the case for some political outcome they already wanted, present their findings to the world, and ask no further questions. This used to be a standard way to do journalism, and it seeped into other areas of intellectual life. When I was in law school from 2010 to 2013, it was intellectually trendy to cite social science research as relevant to legal arguments. Law professors and students of course knew less about statistics and the literatures they were relying on than social scientists, and this made for shaky legal doctrine.

The period during Covid was the height of studies say culture, but also its last gasp. Doctors and those with master’s degrees in public health suddenly declared themselves experts beyond reproach when they were making recommendations that touched on fields like economics, ethics, and mass psychology. The infamous George Floyd letter, in which a lot of people with advanced degrees said you shouldn’t protest unless it is against racism, in which case being out in the streets could be justified on public health grounds, might have been the worst moment for the reputation of official experts in a generation. Trans ideology had a similarly discrediting effect.

There’s an important difference between trusting studies and trusting scientific fields. You’re much better off knowing what the consensus is and what the dividing lines are within a discipline than latching onto random studies, which might not be representative or have all kinds of flaws you didn’t think of but smart people in the field have already addressed. Any individual paper should be seen as another brick added to a wall of knowledge, not as something that forms the building block of a whole new structure. Social scientists have gotten better in their research practices since the beginning of the replication crisis, and journalists and sophisticated analysts are less naive about the significance of whatever the most recent research happens to say.

The self-interested voter hypothesis is (mostly) a myth

Bryan Caplan published The Myth of the Rational Voter in 2007. There is often a default view in politics that people vote their self-interest. Old people should want more spending on retirement programs, women should be more likely to be pro-choice, minorities should be more likely to support affirmative action, etc. Bryan points out an inherent flaw in this view in that in practically no case does an individual voter change the results of an election. So individuals are free to think whatever makes them feel good. In the aggregate, it would make sense for group X to vote for policies that bring it benefits. But random individual A in group X usually has no incentive to support such policies.

Trump’s rise was a shock to the political establishment, and people at first tried to fit it into the self-interested voting framework. There was an idea that working class anxiety drove certain voters into his arms. Over time, this became ridiculous, as Trump governed mostly like a conventional Republican in his first term and his cult of personality grew stronger. When I wrote a report in 2020 with George Hawley using survey data to take apart the idea that economic self-interest was behind support for Trump, it got a lot of attention. Saagar Enjeti invited me on Rising to talk about it, and told me that it changed his mind on this issue.

The idea of self-interested concerns motivating voters for populist candidates is not completely dead. It is in fact still promoted by figures like Batya and Steve Bannon. But note I said that it is the smartest and most perceptive analysts who are getting smarter. The less thoughtful ones are worse than ever. People worth listening to for their ideas, however, have calibrated away from the self-interested voter myth. They’ve applied the lessons of economics and political science, which tell us that people’s politics are generally based on social attitudes and vibes. Among smart people, “economic anxiety” as a way to explain support for Trump has become a punchline.

This doesn’t mean that “citizens vote their interests” is a completely useless heuristic. For example, if you ask people whether we should cut Social Security or raise taxes to deal with the entitlements crisis, public opinion falls along generational lines. Self-interest is probably much better than pure chance at predicting political attitudes. Yet if you put objective economic circumstances into a regression and balance it against psychological predispositions and cultural attitudes, we see that self-interest is a weak predictor of political views.

This is not to say that people don’t vote on “the economy” as an abstract matter. The fates of incumbents are tied to indicators such as inflation and the rate of growth. But rewarding or punishing leaders based on outcomes is not the same thing as favoring certain policies because they are thought to be good for one’s relative situation. Voters seem to use a heuristic of considering whether the economy is good or bad, which political scientists call sociotropic voting. This empirically dominates over what is sometimes called pocketbook voting, which is associated with their own finances or attitudes toward policies meant to help people like themselves. In practical terms, this means Trump can be expected to lose working class support if the economy goes downhill, but not necessarily if he cuts programs meant to help the poor. This is why the president pays a lot of attention to the stock market and economic data while he’s willing to cut Medicaid, food stamps, and Obamacare subsidies. There is no first-principles logic that explains why cultural and sociotropic voting dominate over self-interested voting, but that is what the data says, and smart people understand this a lot better than they did a few decades ago.

Human progress

In 2011, Steven Pinker published The Better Angels of Our Nature, which argued that the world was getting a lot less violent along many different dimensions. He followed this up with Enlightenment Now (2018), making a more generalized case that life has gotten better. You’ll still hear people on the left talk about how climate change suggests that they shouldn’t reproduce, or people on the right say that due to wokeness we’re living under the most extreme form of tyranny in human history.

For more intelligent audiences, however, I think that Pinker’s views have won, and there is a broad understanding that progress is a real thing. This is in part due to books like Better Angels, but also the progress studies circle that has been built around Tyler Cowen, which includes outlets like the highly impressive Our World in Data website, a goldmine of information that is really fun to browse, and the magazine/Substack Works in Progress. You can see the downstream influence of this kind of thinking in the book Abundance and The Argument newsletter and the Institute for Progress think tank, projects that take seriously the idea that liberalism has had significant accomplishments that are worth defending. On the policy front, the proposed NIH budget working its way through Congress incorporates many of the ideas put forward by the progress studies community, including trying to reduce paperwork, along with directing more money to young researchers and funding “people rather than projects.”

Our politics and news keep getting more negative, but your top tier analyst has incorporated into his worldview an understanding that this pessimism is an illusion. The growth of progress studies as a field, which investigates questions like how to make science work better and how to facilitate the adoption of new kinds of technologies, shows the practical payoff of taking seriously the idea of progress as a historical fact and empirical reality.

I think back to the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, and at that moment even smarter figures like Andrew Sullivan and David Frum got caught up in this idea of a clash of civilizations that would require massive sacrifices to win. Eventually, people realized that, as bad as 9/11 was, there was no actual civilizational threat, and when ISIS came along we were generally a lot calmer about what was happening, even as the US used military force to make sure it lost the territory it had under control. Today, there is an understanding that the major problems of the world are mostly solvable or manageable, but bad incentives and political decision-making remain the main obstacles to things getting even better.

What to Expect on the Right and Left

When arguing the discourse is getting dumber, I can point to empirical metrics like the rise of Tucker, Candace, and Rogan in media, along with the entirety of the MAGA movement. It’s harder to prove that other parts of the discourse are getting smarter in the same way. But if you’re here you probably agree with me that people like Matt Yglesias, Scott Alexander, and Tyler Cowen are very insightful, and it is simply true that individuals like them reach more people than ever before. Twenty years ago, there weren’t as many discussions about metascience or the fundamental causes of progress as there are today. At the same time, of course, there was much less discussion then of vaccine shedding or demons attacking famous pundits in their sleep.

Parts of the discourse getting smarter and other parts getting dumber have the same underlying cause. The internet provides faster access to more information. Start out stupid, you find yourself going down an endless number of rabbit holes about Satanic pedophiles, the lost city of Atlantis, etc. If you’re smart, you can read Marginal Revolution over coffee in the morning, enjoy ACX and Yglesias posts while you’re pretending to work, click on some links in those pieces and gain even more knowledge about whatever you find most interesting, listen to Dwarkesh or the NYT podcast on your way home, and once in a while ask ChatGPT to summarize an academic literature that you don’t have time to read. Journalists, especially at the highest levels of the profession, are generally intellectually curious people who care about truth, so are influenced by the better thinkers out there.

Communities getting smarter is a lot harder to notice than communities getting dumber. Many have written about the rise in conspiracy theories and antisemitism. People having more accurate views about polling or the behavior of voters is much less interesting to think about. This means there’s a danger that we end up more pessimistic about the state of the discourse than is warranted.

That being said, I think that the net effect of all this has been to make us stupider. This is because there are a lot more dumb people than smart people out there. So while Candace Owens and Tyler Cowen both reach larger audiences than before, the reach of the former has grown a lot more. The ultimate political manifestation of society getting stupider is of course MAGA. One way to understand Trump is that he’s a kind of Jackie Robinson figure for the intellectually lazy and cognitively deficient. Trump does clearly have a certain shrewdness, even at his advanced age, but his disordered emotional state and indifference to truth mean he thinks and speaks like a dumb person.

Increasingly, the human capital divide is now in many ways more important for our politics than ideological differences. Is Trumpism more or less pro-market than the contemporary Democratic Party? It’s a hodgepodge, in the sense that Biden wanted things like higher taxes and more extensive civil rights protections, but didn’t implement major tariffs or have the federal government take stakes in various large corporations. I think that when historians look back on the Trump era, they will be more likely to note the collapse in norms surrounding things like truth and corruption and the existence of a fair justice system than policy changes. Likewise, think about how in late 2025 the most popular podcasts in the country among right-wingers on Spotify were Tucker and Candace, while the most popular among those on the left were The New York Times and NPR. An alien investigating our culture would find the ideological differences between the two tribes less interesting than the fact that one side is plugged into reality and the other simply is not. Tucker’s ideological differences with the NYT pale in comparison to how much poorer he is as a source of information and in terms of his ability to provide a rational model of the world.

The big question to me is whether Trump has given us a unique level of human capital polarization, or it gets worse going forward. I believe that to some extent there’s a natural tendency for highly intelligent people to distribute themselves on both sides of the political spectrum. If one faction is completely devoid of brains, then there’s an opportunity for smart people to get ahead on that side. This is why if you’re a student at a top law school, you’re more likely to get a prestigious fellowship as a conservative than liberal, since judges appointed by Republicans have a shallower pool to pick from.

There are of course other factors determining political attitudes, so smart people don’t end up anywhere near evenly split. I’m just saying that there are forces preventing the human capital gap from becoming too wide. At the same time, we may have reached an equilibrium in that there is little prospect of the right recovering from its brain drain. There will still be smart people like JD Vance who see opportunities to get ahead within conservatism. But they will play their role in the context of being part of a low human capital movement, and will have to either hide their smarter opinions and ideas, or subconsciously work to become dumber. Musk is another example of a smart person who operates under circumstances in which the pull of the low human capital horde is so overwhelming that he has become like his fans.

So increasingly higher levels of human capital polarization is one possible future. This would imply that Democrats get smarter and Republicans dumber. We can see a lot of indications of this in the last few years, with the right embracing MAHA, white nationalism, and high tariffs, and the left starting to moderate on social issues and listening to Ezra and Derek on abundance. Perhaps this accelerates, and the right goes even more populist, purging the free marketers from conservatism and ending up stupid basically across the board. This is the dream of people like Bannon, who want to rule over the wreckage of the conservative movement, and in the long run they may have the edge.

It’s probably not going to be that simple though. Note how HHS recently announced new guidance explaining how drug companies and researchers can incorporate Bayesian statistical methods into clinical trials investigating the safety and effectiveness of drugs. I saw a funny tweet afterwards joking that half of HHS is composed of MAHA lunatics while the other half reads Scott Alexander before they go to bed, so they compromised and banned both vaccines and poor statistical practices. In response to the announcement, Nicholas Decker praised the work of the FDA, saying that RFK probably doesn’t know much about what it is up to. For another take, arguing that the FDA’s top ten listed accomplishments have mostly been either bad or ineffective, see here, though even the author of that piece believes there have been useful reforms.

All of this shows that one major faction in politics being completely taken over by low human capital can have advantages for smart people who want to do great things. Picture the following image: a train with an angry face and the engine saying “Racism, Conspiracy theories, Hatred of libs.” All these maniacs are sitting comfortably in their seats. But holding on for dear life off the sides are people labeled “Rationalists,” “Nuclear power advocates,” and “Free marketers.” I’m no cartoonist, but I asked ChatGPT to draw this, and here’s what I got.

That’s pretty good! Trump gave us Operation Warp Speed, and also a war on vaccines. Shrewd observers notice that the right has less brains and fewer gatekeepers. This means that if you’re a smart person who wants to just achieve power, the current political alignment provides a shortcut. At the highest level of success you get Tucker and JD Vance, people who are either evil or simply oriented toward money or power. At the same time, if you have good ideas that you would like to see implemented, you also have opportunities in front of you. Basically, any professor or academic who has said nice things about Trump in the last few years had a good chance of being hired in this administration if they built the right networks. Low human capital fuels the train, but it doesn’t really have views on whether or not government should use Bayesian statistics in clinical drug trials, and therefore views that have been unjustifiably excluded from mainstream institutions get a hearing.

Taking a broader perspective, the most pessimistic scenario is that low human capital just wins, fully consolidating its gains on the right and beginning to eat the left. With iPhones and ubiquitous social media less than two decades old and AI just getting started, society has the potential to continue getting much stupider. As the party of non-elites, the stupidity hit the right faster and harder. The Trump cult consolidated and high human capital with conservative leanings turned into refugees, either going to the left or becoming politically homeless. For this reason, Democrats began to get smarter. But on a longer time horizon, we’ll maybe eventually get Democratic versions of Joe Rogan, RFK, Tucker, etc. (RFK and Rogan themselves started out on the left!) who will come to dominate the left the way they have dominated the right.

If rationalism and progress studies are the height of high-quality content and MAGA is at the low end, we can maybe hold up wokeness in between as midwittery in its more extreme form. We can perhaps throw the antimonopoly movement in the same bin. Ezra and Derek are winning the debate on the left now, but I’ve been disturbed to see the rise of More Perfect Union. One of their co-founders was recently bragging that they had the fastest growing politically left-wing YouTube channel in the fourth quarter of 2025, behind only Turning Point USA and the Shawn Ryan Show, and just ahead of Candace and Tucker. The rise of Hasan Piker and the cult-like following of Luigi, along with the election of Zohran Mamdani and the continuing popularity of figures like Bernie Sanders, AOC, and Elizabeth Warren, are additional reasons for concern. That said, Zohran moderating a bit is a good sign that Elite Human Capital having a seat at the table can even under more difficult circumstances pull the left in a better direction.

I think that the right being the side of low human capital over the long haul is close to inevitable. The question is what the balance of the left will be between the more rational set and midwittery. If Enlightenment values truly triumph on the left, then what to do in politics becomes an easy decision, suggesting the priority should be to try to crush the racist and conspiratorial right. But if the Luigi and Hasan Piker fans come to dominate the left, smart people who want to move society in a healthier direction will have to grab on to one of the two trains and decide whether they’re more able to tolerate and work within a resentful, anti-rationalist culture centered around the hatred of foreigners and appealing to stupid people, or a resentful, anti-rationalist culture centered around the hatred of the rich and appealing to midwits.

One reason to be optimistic is that good ideas are likely to have staying power, even if they are drowned out by idiocy in the short run. If you think, per the cartoon above, of politics as involving smart people sometimes getting to the destination of political power by holding on to trains powered by the motivations of haters and fools, useful ideas will still be there regardless of which way the political winds blow. Most people are indifferent to questions like how clinical drug trials should work or at what level of government zoning decisions can be made. Well-informed intellectual and political movements composed of thoughtful and highly motivated actors might therefore consistently find opportunities to impact policy in a positive direction. They could do this in the context of a political culture dominated by previously unheard of levels of stupidity, as life continues to get better for most people in the world.

Sobering article but it assumes that the train stays on the track. While I agree that the left is moderating, and that more effective leadership (than Biden, Schumer et al.) is likely, the folks on the right are agressively trying to derail the train. Repeated violations of the Constitution and court orders. Threats to future elections. Destruction of government capacity. Teaching Americans to love autocracy because they hate the left more. Pushing policies that make climate change worse in the face of a 1.7C estimate temperature rise over preindustrial for 2027. Destabilizing both the American and the world economy, as well as international relations, through the use of tarrifs and hostility to other countries. How do you alienate Canada? So I get this theory but the obvious question is what happens if the train is derailed. That's ommitted from the article but seems like a very possible scenario.

No offense to Tyler Cowen or Matt Yglais, they probably are a step up from traditional media, but I wouldn't put them in the same sentence as Scott Alexander.

Is modern political discourse on the internet more sophisticated than it used to be on legacy media? The upper portion of mainstream discourse is probably more nuanced than it used to be because the internet has made ideas more accessible. But at the highest level there's much less influence from big name political philosophers than there was in the mid 20th century.

Whatever you might think of their politics I don't think Foucault or Derrida would be impressed by the sophistication of an Ezra Klein think piece.